I toured two Ellis Island hospitals that have been abandoned for 65 years. Here's what they're like inside.

Frank Olito

- When Ellis Island was in operation during the early 1900s, immigrants who were deemed too sick or disabled to be admitted into the US were sent to hospitals on the south side of the island.

- Today the hospitals are abandoned. In 2019, I took a tour back of the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital and the Contagious and Infectious Disease Hospital.

- Inside, the walls are crumbling and the ceilings are falling down, but most of the structures have remained intact.

- The morgue still has the cooling chambers where dead bodies were kept, and the chief of medicine's house still stands on the edge of the island.

- The hospital was known for its pavilion wards, which were large rooms that housed 20 patients with the same illness. Today, the large rooms are empty and deteriorating.

For many immigrants coming to America, Ellis Island was the entryway into their new lives. The visit to the island off the coast of Manhattan would be a sojourn for most, but 2% of immigrants never made it to the mainland.

Instead, they were turned away and sent back to their home countries, while others were sent to the hospitals on Ellis Island to be treated for diseases like measles and tuberculosis.

Today, Ellis Island is a bustling museum that welcomes 4 million tourists each year. But the hospitals on the south side of the island are closed to the general public and have been left in ruin for 65 years.

In the fall of 2019, I gained access to the hospitals through a special hard hat tour operated by Save Ellis Island, a nonprofit organization devoted to rehabilitating the island. Here's what it's like inside the abandoned and dilapidated ruins.

Aboard the ferry from Manhattan to Ellis Island, I began retracing the steps so many immigrants took over 100 years ago.

The ferry left Manhattan from Battery Park, and the first stop was the Statue of Liberty. For the immigrants coming to the US, the Statue of Liberty was their first glimpse of America. But their ships didn't stop there. Instead, they stopped at Ellis Island, a processing hub where every immigrant had to be examined and cleared for entry into the country.

To really follow in the immigrants' footsteps, I decided not to get off at the Statue Liberty — which has been converted into a park for tourists — and instead headed directly for Ellis Island.

From the ferry, I caught my first glimpse of the hospital that now stands in ruins near Ellis Island’s main building.

The hospital complex consists of the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital and the Contagious and Infectious Disease Hospital.

As I approached the main building, I was reminded that Ellis Island was a source of hope for many immigrants.

Opening in 1892, Ellis Island processed 12 million immigrants throughout the 60 years it was open. In its peak year, 1907, about 1.25 million immigrants were admitted through the island.

While Ellis Island was meant to be passageway into a new life, it was also a source of anxiety and fear.

For most, it took under a day to get through the immigration process and gain access to the US. But not everyone who made the journey across the sea made it into the US. About 120,000 were denied entry and sent back to their home country. Meanwhile, immigrants who were deemed too sick or disabled to be admitted into the US were sent to the hospitals on the south side of the island.

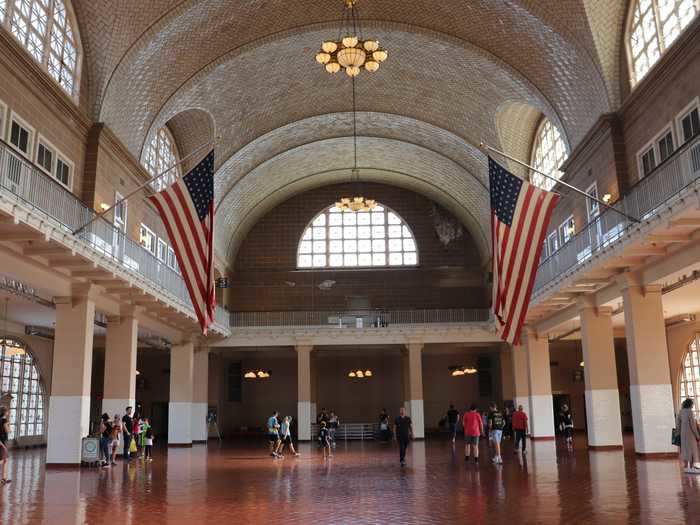

Immigrants' fates were chosen in this room. Here, doctors took just six seconds to examine each immigrant to determine if they were healthy enough. If not, they were sent to the hospital.

The doctors in this large room in Ellis Island's main building would look for any physical or obvious illnesses they could diagnose immediately. It could be anything from a limp to the measles. These people wouldn't immediately be sent back home. Instead, they would be taken to the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital or the Contagious and Infectious Disease Hospital, which were on nearby separate islands.

Ellis Island is actually made up of three smaller islands which were not-so creatively named Island 1, Island 2, Island 3.

Island 2 was built just 100 yards away from the main building in 1902 to house a hospital that could treat 125 people. Eventually, two more small hospitals were built on this island to accommodate the growing number of sickly immigrants. Eventually, this general hospital had 750 beds, according to The New York Times.

In 1907, Island 3 was built to house the Contagious and Infectious Disease Hospital.

If an immigrant came to this diverging hallway, it meant they now had a 50-50 chance of making it into the US.

An immigrant who was sent down the left hallway would be heading to the general hospital, and the odds were likely that they would be cured of whatever ailments they had. They then would be allowed into the US.

If they were taken down the right hallway, it meant they were going to the Contagious and Infectious Disease Hospital and their odds of successfully immigrating dropped dramatically.

Just outside the main hospital, I was impressed by the opulent architecture.

Looking at the beauty of the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital, it was almost easy to forget that around 1 million people were treated for illnesses and disabilities in this building. For some, this would be their last stop.

On my tour, the first stop inside the building was the laundry room, which washed about 3,000 bed sheets per day.

Here, you can see the washing machine in the background and the dryer in the foreground. The toilet in the middle of the room was bizarrely left there when the hospital closed, and no one knows why.

The hospital was ahead of its time because the staff understood the importance of cleanliness in stopping the spread of germs.

Cleanliness was so important they would even sterilize mattresses in this chamber.

Today, the rusted door is still ajar, seemingly stuck between two worlds.

Next door is the Psychopathic Building, which housed any immigrant with a mental disorder.

If an immigrant was taken to the Psychopathic Building, they would never be allowed to live freely in the US. This building essentially acted as a holding cell until they found placement in one of the asylums throughout the US. These immigrants would be confined to an institution for the rest of their lives.

Inside, the ceiling is crumbling and paper has fallen from the walls.

These rooms acted as jail cells for immigrants deemed mentally ill. Today, the floors have been chewed up by weather and time.

While some rooms are badly damaged, others are filled with rusted and ruined furniture.

When I noticed the rusted filing cabinet in this room, I imagined it had once been filled with patients' files. Today, the drawers are empty, much like the rest of this hospital.

In the bathroom, the stalls still stand, but the sink lies lopsided on the floor.

Some parts of the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital still remain eerily intact, and, for me, that was the creepiest part.

Adjacent to the Psychopathic Building is the maternity ward.

Doctors would pull a pregnant immigrant out of line if they felt she was too far along to travel safely to the mainland. The women were forced to stay at the hospital until they gave birth. In fact, 350 children were born on Ellis Island.

The tour did not allow me inside this building.

After a brief tour of the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital, it was time to make my way over to the Contagious and Infectious Disease Hospital.

Another 100 yards away on Island 3 sits the Contagious and Infectious Disease Hospital. Here, the length of stay for patients was between three weeks and a year.

Once inside, I could immediately feel the sense of dread in the long, dark hallways.

While most of the windows were boarded up, small slits of light snuck through, offering glimpses of the rundown building.

The hallways lead to rooms that are completely crumbling.

My tour guide did not explain what this room was initially used for.

Meanwhile, other rooms are strangely filled with aging chairs.

In this part of the hospital, there were several rooms completely filled with chairs. Most of them were stacked on top of each other, while others were pushed into corners.

On my tour, in the morgue, small doors on a giant refrigerator were open, offering a glimpse into darkened chambers inside.

The refrigerator once helped preserve dead bodies.

The room also acted as an operating theatre. More experienced surgeons would perform surgeries to educate the younger doctors.

Strangely, historians cannot find a single photo taken in this room while it was in operation.

Walking from the morgue to our next stop on the tour, I noticed how some parts of the building were completely missing.

Every now and then, I came across windows that were shattered, walls that were missing, and ceilings that were collapsed.

The hospital had 11 pavilions, which were large rooms that housed 20 patients with the same disease at the same time.

Early on, doctors and nurses in this hospital learned that putting a person with measles next to a person with tuberculosis would greatly decrease their chances of survival. So, they implemented a creative and successful pavilion-style layout that originated in Virginia during the Civil War. Each pavilion or ward was designated for a specific disease. The picture above, for example, shows a measles ward.

The most important feature was the windows. Since there was no real treatment for some of the diseases at the time, the only thing nurses and doctors could do was open the windows and let in fresh air.

I realized each window cruelly looked out on the Statue of Liberty, almost teasing each patient. Lady Liberty was meant to be a beacon of hope and symbolize the start of a new life. For the people in this room, that new life was just out of reach.

The tuberculosis ward, however, looked different because of the severity of the disease.

Tuberculosis affects the lungs and can be transferred through the air. Therefore, tuberculosis patients in the Contagious and Infectious Disease Hospital had to be quarantined into their own rooms. Each patient's room was off this long corridor.

Each room in this ward was equipped with two sinks — a necessary feature to stop the spread of tuberculosis.

Patients had to spit up phlegm, blood, and mucus into the smaller sink so that it wouldn't contaminate the rest of the water supply, which was flushed into the river. The spit and other TB-contaminated products in this separate drainage would eventually be brought to a nearby powerhouse and incinerated.

In the entrance to each ward, nurses' stations are now covered in dust.

I saw dust covering the places where medicine, needles, and other supplies were once stored.

Down the hall is the kitchen, which served 500 people each day.

In here, there were three types of meals prepared: a meal for patients with regular diets, a meal for patients with lighter diets, and a meal for nurses and staff.

Today, the kitchen is mostly empty, except for a range hood that hangs from a dilapidated wall.

The large, wooden refrigerator once held the hospital’s chilled foods.

Today, the fridge is covered in dust and completely empty.

Stepping out of the kitchen, I took one last look down the long hallway that seemed to stretch on endlessly.

The boarded-up windows, the ill-lit rooms, and the crumbling facade all made for a terrifying tour. But it wasn't over yet.

Next door to the Contagious and Infectious Disease Hospital is the chief of medicine’s home.

The chief of medicine lived onsite with his wife and children. Other senior doctors lived in this home as well.

Upon entering the home, I was immediately greeted by a grand staircase that led to the second floor.

There are three bedrooms on the second floor, but it's not considered safe to climb the stairs today.

On the tour, I was told that children who lived in this house used to hide from doctors under the staircase.

Although the living room is now covered in dust, I could still see the home's former grandeur.

I was told this room was the best during Christmas, with stockings hanging from the fireplace and a tree standing in the corner. Now, it's completely abandoned.

The kitchen came equipped with a cupboard, a stove, and two sinks.

These days, the kitchen is dark with only a few beams of light seeping into the room.

Back outside, I took one last look at the massive hospital complex and was reminded of all the people who'd once been there.

The hospital was later converted into a Coast Guard training center and played an important role in World War II. In 1954, Ellis Island and its two hospitals closed for good, but it still stands today as a monument to all the people who fought so hard to make it to America.

- Read more:

- Built in 1829 and abandoned since the '70s, Philadelphia's Eastern State Penitentiary is one of the creepiest places in America. Here's what it's like inside.

- Take a look inside the famously creepy Winchester House, which has 160 rooms, staircases that lead to nowhere, and doors that open into walls

- The history behind 40 of the most haunted places in America

- New York City owns a creepy island that almost no one is allowed to visit — here's what it's like

READ MORE ARTICLES ON

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement