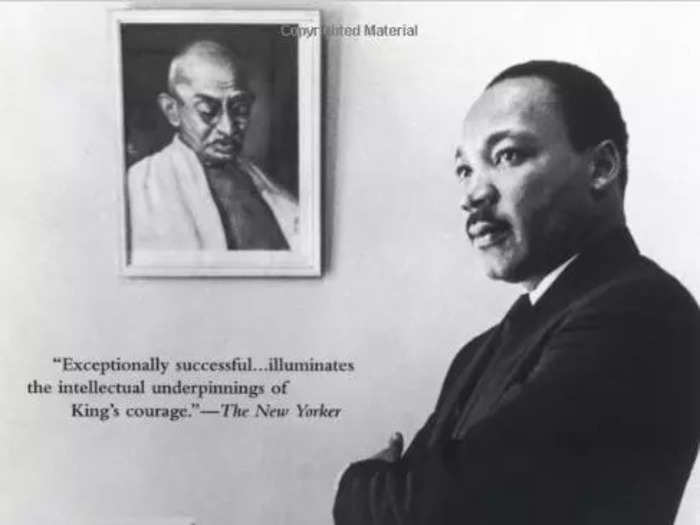

32 things you probably didn't know about Martin Luther King Jr.

Savanna Swain-Wilson

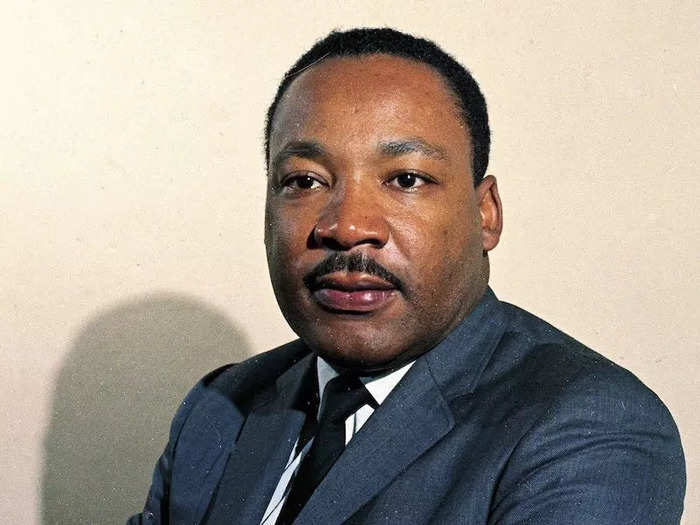

- Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was a civil-rights activist who helped end segregation in the US.

- Martin isn't his given name — he was born Michael King Jr., after his father.

He is the only American, other than George Washington, whose birthday is a national holiday.

Martin Luther King Jr. Day became an officially observed holiday for schools, banks, and federal offices across the US in 1986 — making him the first non-president to have his birthday become a national holiday.

But it took a while for all 50 states to get on board with honoring the activist.

South Carolina was the final state to officially observe the national holiday in 2000.

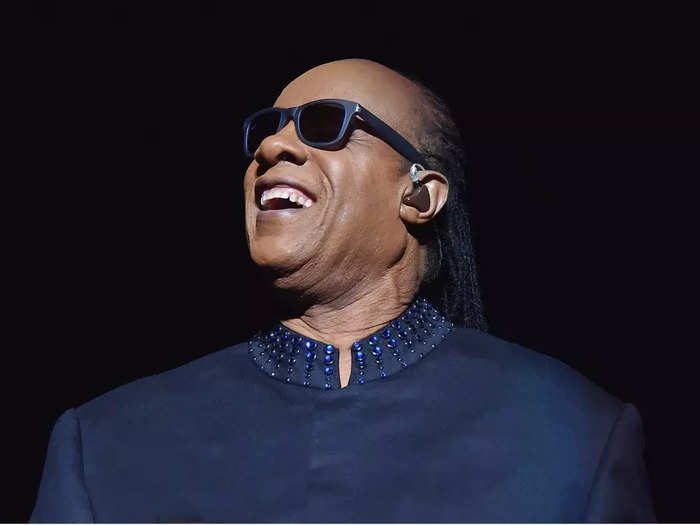

Stevie Wonder wrote a song to honor the late activist.

In the wake of Dr. King's death in 1968, several notable figures found ways to honor him and aid in the push for MLK Day.

By the late 1970s, President Jimmy Carter pledged his support of the holiday, but the King Holiday Bill didn't pass in Congress.

To help garner support in the following years, Stevie Wonder wrote and recorded his song "Happy Birthday" in honor of Dr. King. He also joined the reverend's wife on a four-month tour to advocate for the holiday.

After the tour, they delivered a petition to the speaker of the house with 6 million names on it.

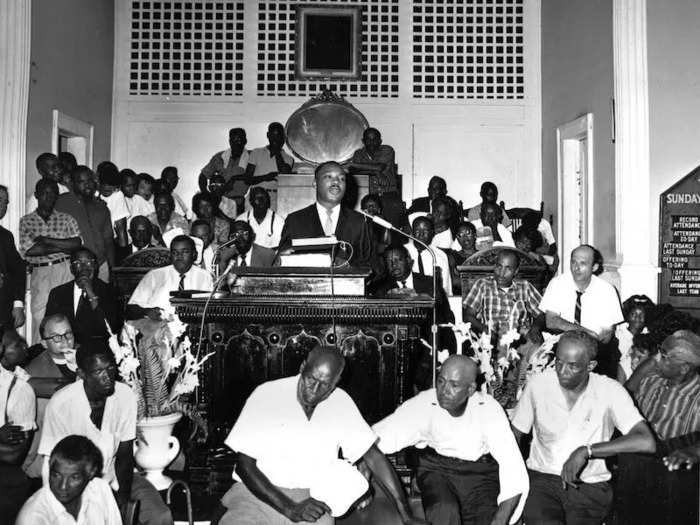

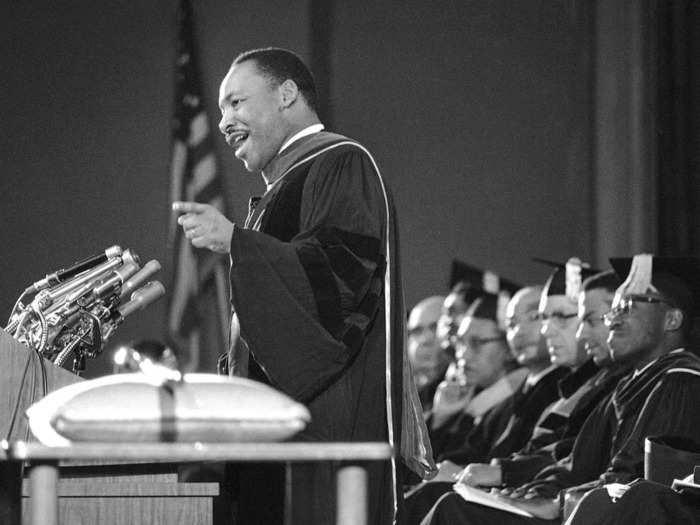

Dr. King was always a natural in front of a crowd.

Dr. King's public-speaking talents date back to his teenage years when he won an oratory contest in Georgia for speaking on a topic titled "The Negro and the Constitution" when he was a teen.

According to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford, in the orientation, he highlighted the contradictory nature of the US constitution in the context of discrimination.

His name wasn't originally Martin.

Dr. King's given name was actually Michael, after his father, the Rev. Michael King Sr.

In 1934, after King Sr. attended an international Baptist conference in Germany where he became inspired by the teachings of 16th-century religious thinker Martin Luther, he changed both his name and his son's.

At the time, Dr. King was already 5 years old, so he remained "Mike" to his closest friends and family for the rest of his life, according to Time.

He was passionate about fighting for racial justice from a young age.

In "The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.," Dr. King recounted his first personal experience with racism and segregation.

As a child, his white friend suddenly refused to play with him anymore, and he credited this betrayal as the moment he first became interested in fighting against racism.

He was kicked out of the first grade, and he ended up skipping two more years of school later on.

Dr. King enrolled in first grade at age 5, which was too young per the school's entry requirements, so his teacher expelled him.

Years later, he was able to skip both the ninth and 12th grades because of his academic achievements.

Dr. King enrolled in college when he was 15.

Instead of finishing the 12th grade and going through a formal high-school graduation, Dr. King was accepted into and enrolled at Morehouse College at age 15, where he completed a Bachelor's degree in sociology.

One of his first jobs was working for a newspaper.

From an early age, Dr. King had an established paper route.

His work ethic allowed him to be promoted, and he became the youngest assistant manager for The Atlanta Journal delivery station at age 13.

The reverend wasn't always steadfast in his faith.

Although he would later become a religious leader, as a teenager, Dr. King had a very different view of his faith.

In his autobiography, he wrote that he wasn't afraid to openly question everything he had been taught, even when it got him into trouble.

"At the age of 13, I shocked my Sunday school class by denying the bodily resurrection of Jesus," he wrote. "Doubts began to spring forth unrelentingly."

Dr. King wasn't inspired to become a minister until college.

Dr. King didn't always plan on following in his father's footsteps and becoming a minister.

But according to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford, after he took a bible course with Dr. George D. Kelsey, he was inspired to use ministry as a medium for social justice and racial reform.

He was valedictorian of his class at Crozer Theological Seminary.

Given his rich interest in academia, it makes sense that Dr. King graduated at the top of his class.

He was named valedictorian and honored with a fellowship that covered part of his graduate-study expenses.

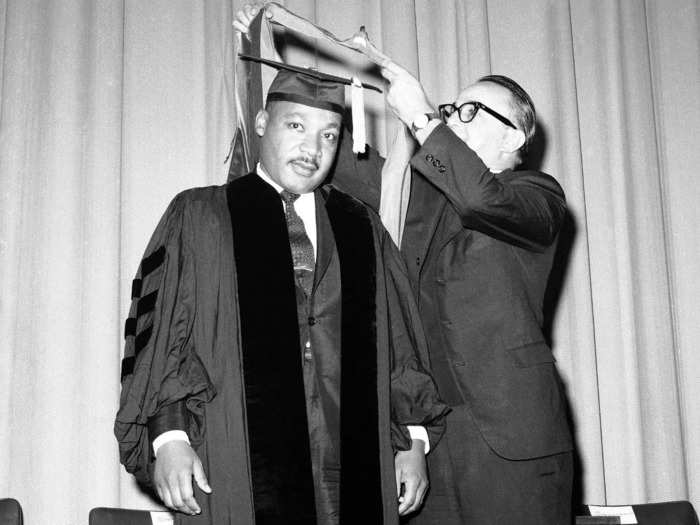

He earned his Ph.D. in systematic theology at Boston University.

On top of receiving two Bachelor's degrees (one in sociology from Morehouse College and the other in divinity from The Crozer Theological Seminary), King went on to earn a Ph.D. from Boston University in 1955, making him a doctor of philosophy.

He was also awarded at least 20 honorary degrees in later years.

As if earning three degrees as a student wasn't enough, Washington State University reported that Dr. King was awarded honorary doctorates from Howard University, Bard College, Yale, Wesleyan, and many other higher-education institutions across the US and the world.

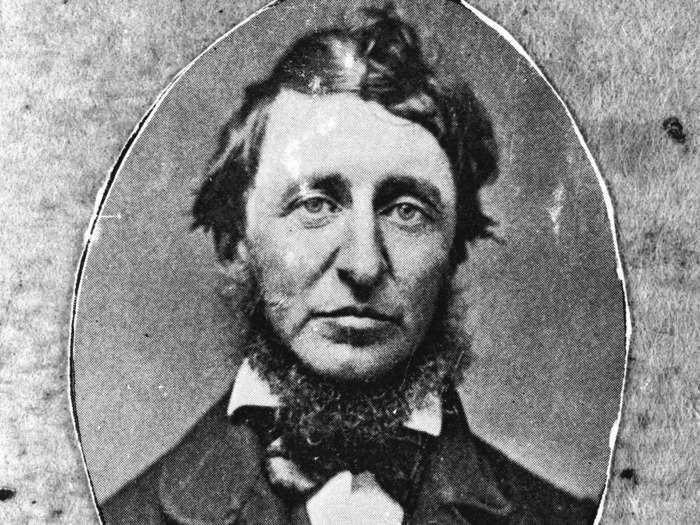

American essayist Henry David Thoreau had a profound impact on his civil-rights career.

Throughout most of his life, Dr. King was a voracious reader. According to Atlanta Black Star, he enjoyed delving into the works of great philosophers and thinkers like Socrates, Rousseau, and Aristotle.

But of all the great texts that influenced him, the essay "Civil Disobedience" by Henry David Thoreau was perhaps the most impactful.

According to his autobiography, Dr. King said Thoreau's belief that an individual should not cooperate with an evil system greatly influenced his worldview. It also inspired his belief in his own ability to enact social change at the individual level.

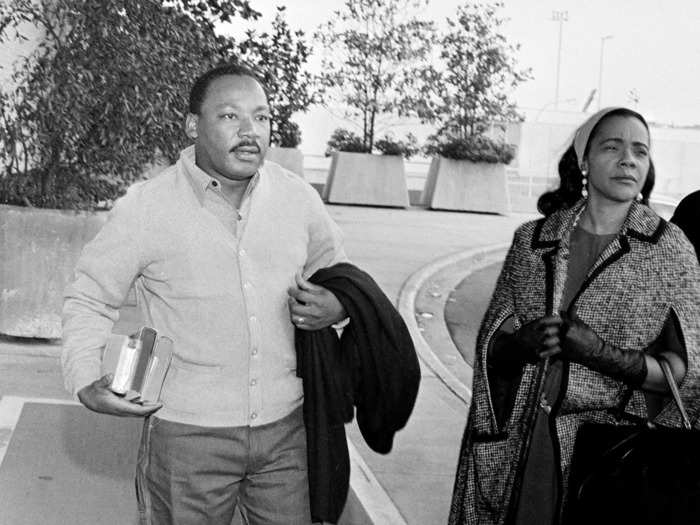

He first met his future wife over the phone.

While studying at Boston University, Dr. King lamented to friends that he had yet to meet any woman he seriously liked. He then reached out to his friend, Mary Powell, who suggested he meet Coretta Scott.

The couple had their very first interaction over a brief phone call, during which they agreed to meet in person.

At the time, Scott was studying opera at The New England Conservatory for Music and hoped to be a concert singer.

Dr. King wrote in his autobiography, "She was a mezzo-soprano and I'm sure she would have gone on into this area if a Baptist preacher hadn't interrupted her life."

He called Boston his second home.

After spending several of his young-adult years in Boston, Dr. King reportedly referred to it as his second home.

He returned to the New England city several times throughout the rest of his life.

Dr. King and his wife had an unusual honeymoon.

Dr. King married Scott on June 18, 1953, in Alabama.

After enjoying a beautiful ceremony lead by King Sr., the couple looked for a place to stay for the night.

At the time, no hotels in their area welcomed black couples as guests, so, according to Brides.com, the pair spent their first night together at a family friend's house — but he happened to be an undertaker who worked out of his home.

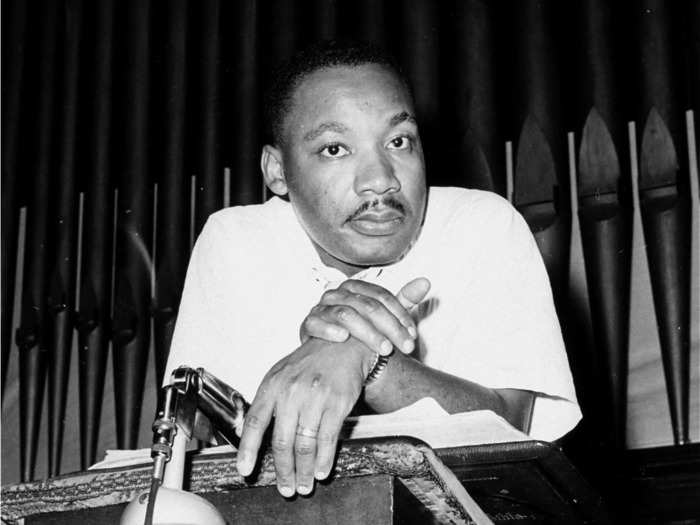

He didn't expect to become a civil-rights leader.

According to The New Yorker, the King family moved from Atlanta to Montgomery, Alabama, when the famous 1956 bus boycott — a citywide protest against racialized segregation on public transit — began.

At the time, King was only 26 and pretty much unknown in activist spaces, though he had previously expressed interest in social justice.

He originally opposed the boycott because he worried that it was unethical to put people's jobs at risk.

But when he realized the ultimate goal behind the protest, he volunteered to use his church's basement as a meeting spot for boycott organizers. During their first meeting, the group elected Dr. King as their president because no one else stood up to take the role.

He then wrote his very first public, political speech in less than an hour.

He wrote six books throughout his life.

His collected works include "Stride Toward Freedom," "Where Do We Go From Here," and "Why We Can't Wait," which all document the rise of civil-rights movements in the US.

Additionally, he published a book of his most-requested sermons, a collection of his broadcasted addresses, and an autobiography.

He spoke at over 2,500 events and gave hundreds of addresses a year.

During his short, 12-year career in the public eye, Dr. King delivered an astounding number of public speeches.

It's estimated that between his weekly sermons at church and media appearances, he spoke an average of 450 times per year, according to CNN.

Although the famed "I Have a Dream" speech will always hold a special place in history, it certainly wasn't the only memorable address he delivered during his life.

Some people believe his last speech foreshadowed his death.

The day before Dr. King was assassinated, he gave a speech in Memphis, Tennessee, to offer support for sanitation workers who had received unfair treatment by their bosses.

The goal of this address was to push for union representation, safer working conditions, and living wages.

He told the crowd, "And I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land."

In the aftermath of his death, some people found the language he used to be an eerie indication that he knew his death was imminent.

He won a Grammy award.

One of Dr. King's most controversial addresses went on to receive a high honor.

The speech, referred to as "Why I Oppose the War in Vietnam" and "Why I Am Opposed to the War in Vietnam," was recorded on vinyl and earned him a postmortem Grammy for best spoken-word recording in 1970.

He almost died years before his assassination.

According to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, in 1958, a woman approached Dr. King at a book-signing event in New York City and stabbed him with a letter opener.

The attack resulted in a life-threatening injury close to his heart, but he received prompt emergency medical care and survived.

His imprisonment helped JFK get elected.

In October 1960, Dr. King was jailed for participating in a sit-in protest at a Georgia department store. At the time, Senator John F. Kennedy (JFK) was running against Richard Nixon for the US presidency.

According to Time magazine, although Kennedy was a registered Democrat, his views on civil rights and racial justice had been unclear.

But upon learning of the reverend's unjust treatment by the police department, a key advisor told Kennedy that his response to the situation would determine his voter turnout in the election.

As a result, Kennedy called Scott King and personally offered her his support.

Many historians credit this action to the large Black voter turnout in the 1960 election and Kennedy's eventual win.

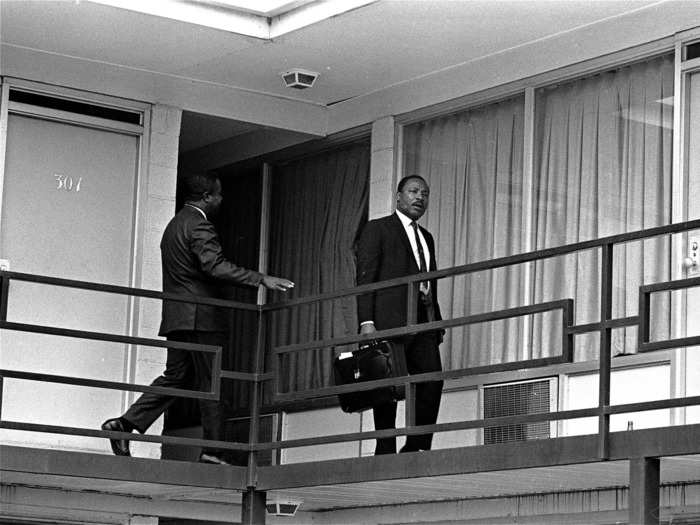

Someone else at the motel died on the day of Dr. King's assassination.

According to The New York Times, one of the staff members who worked at the hotel where Dr. King was assassinated died shortly after the reverend did.

The motel owner's wife was so traumatized by the sight and sound of his death that it caused her to suffer from a fatal stress-induced heart attack.

His political position became more radical over time.

Throughout the 1960s, the scope of Dr. King's activism work went beyond civil rights and into economic justice.

He increasingly used his platform to advocate for causes like guaranteed annual income and health care.

But he also vocalized his strong opposition to the Vietnam War, which caused him to lose a significant amount of American approval, according to Jenn M. Jackson's MLK feature for Teen Vogue.

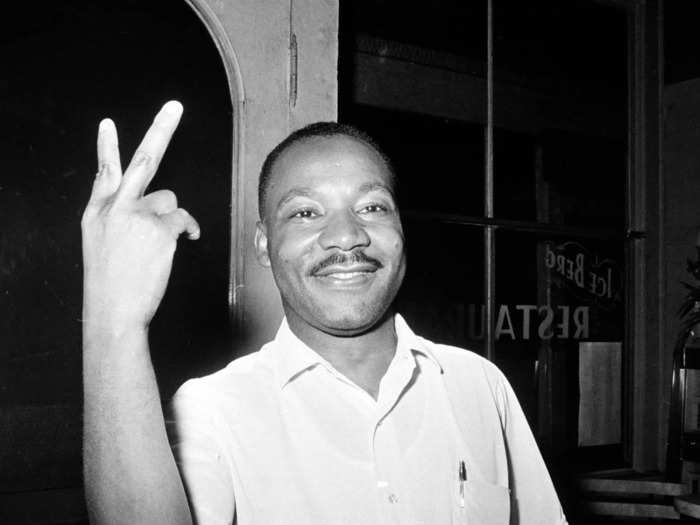

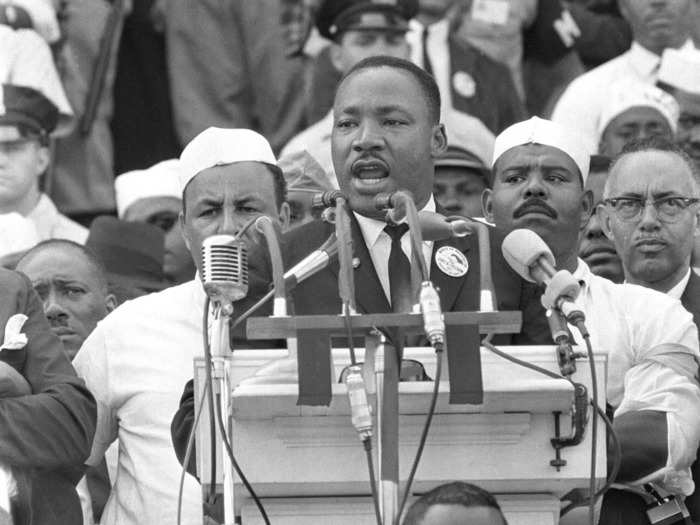

The most memorable part of his "I Have a Dream" speech was unplanned.

During the 1963 March on Washington, Dr. King delivered a monumental speech that had been well-prepared by his speechwriter, Clarence Jones.

But the more he spoke in front of that 250,000-person crowd, the more impassioned he grew, which led him to go off course toward the end of the speech.

Those famous, poetic lines that nearly everyone in the US can quote — "I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up … " — were improvised, according to PBS.

He spoke around the world in countries such as India, Ghana, and England.

According to History.com, once Dr. King became president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he began traveling all over the world to deliver speeches about the importance of fighting for racial equality.

Some of his notable trips include his visit to Ghana, where he celebrated the country's independence, his overnight stint in the UK, where he accepted an honorary degree from Newcastle University, and his pilgrimage to India, where he met the followers of Mahatma Gandhi.

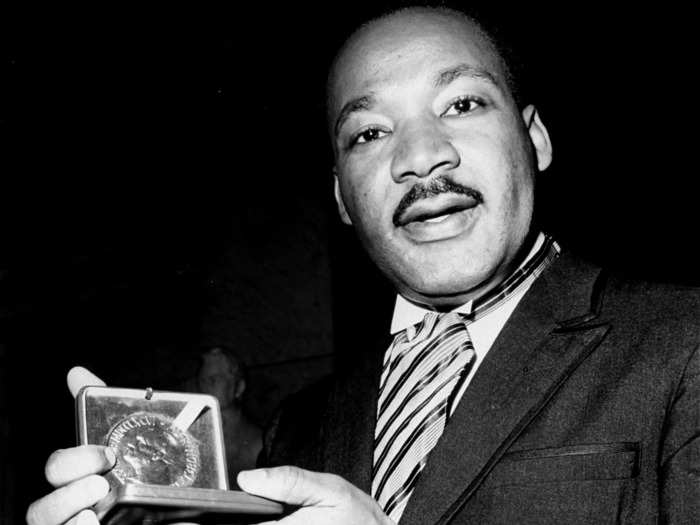

He is still the youngest man to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

In 1964, King received this global honor for his unwavering commitment to civil rights, nonviolence, and helping the US government move toward making discrimination unlawful.

He was 35 years old then, making him the youngest male recipient to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

But five women — Malala Yousfazi (17), Mairead Corrigan (32), Tawakkol Karman (32) Betty Williams (33), Rigoberta Menchú Tum (33) — received the award at younger ages.

He is honored in cities all over the world.

There are currently dozens of statues and monuments commemorating Dr. King across the US and the world — including one in England at Westminster Abbey and another in Cuba.

And that doesn't include the countless schools and 1,000-plus streets named after him across the globe.

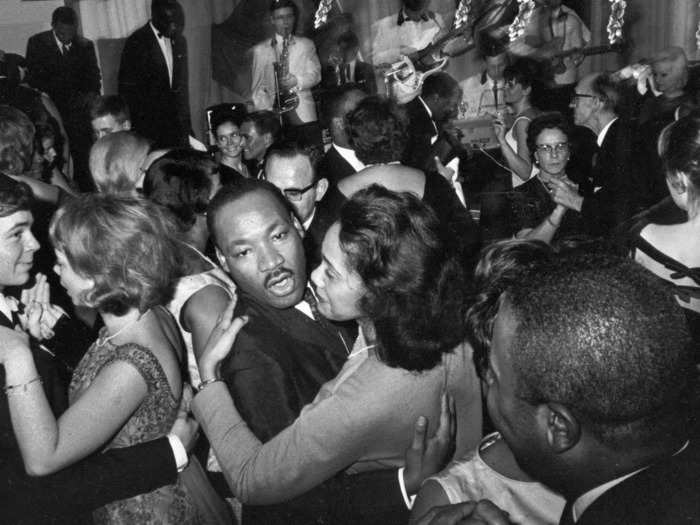

He had a deep appreciation for gospel and jazz music.

Dr. King's religious upbringing greatly influenced his love for music. His mom was even an organist for the church he attended during his childhood.

From the time he was a young boy, he sang in a gospel choir and believed in the healing power of music, especially hymns. He later went on to call singers like Mahalia Jackson and Nina Simone his favorite artists.

And according to The International Musician, he enjoyed jazz music, too.

He even traveled to Berlin and delivered the opening address for the 1964 Jazz Festival titled "On the Importance of Jazz."

Dr. King's final conversation involved a simple request.

According to biographer and historian Taylor Branch, Dr. King's final conversation was with a saxophonist named Ben Branch.

The reverend reportedly asked the musician to play his favorite song, the hymn "Precious Lord, Take My Hand," at an event they were both scheduled to attend later that evening.

But Dr. King never got to hear Branch's rendition of the song. Moments after making this request, he was assassinated on the balcony outside his room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

Read More:

- 7 of Martin Luther King Jr.'s family members who have continued his legacy

- Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat 64 years ago — here are 15 surprising facts about her

- 15 iconic moments in the LGBTQ rights movement from the last decade

- 21 of the most important human rights milestones in the last 100 years

READ MORE ARTICLES ON

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement