Here's the atrocious way some villages in the Himalayas treat girls who are menstruating

In the isolated hills of Legudsen village, in the far western region of Nepal, Reuters photographer Navesh Chitrakar set out to document a tradition that threatens the lives of women and girls.

Each month, menstruating women are exiled from their homes and families, and forced to sleep in sheds, stables, or outhouses, often with little protection from the elements.

This ritual isolation, called chaupadi, stems from a Hindu belief that secretions from menstruation and childbirth are religiously "impure." Others fear that breaking the tradition would bring devastating bad luck, such as failing crops and dying livestock.

And so when that time of month rolls around, women who practice chaupadi are not allowed to enter a house or pass by a temple.

They cannot use public water sources, touch livestock, or attend social events. Pictured below is a clean shawl hung out to dry, after the wearer's period ended.

Here, a family member offers food to women practicing chaupadi. The person who brings the food should not touch the dish, because menstruating women are considered "untouchable."

"As I worked on this story, I realized that chaupadi does not just bring discomfort and isolation to the women practicing it — sometimes they even have to pay with their lives," Chitrakar says.

The rickety sheds, outside the home, often lack a proper door or window, so wild animals and snakes can get in, as well as freezing chills, and in some instances, rapists. Other women have died from asphyxiation or burned to death when they built fires in the cramped sheds.

According to a government officer with the local women and children's office, seven women have died while observing chaupadi in the Achham District, where Chitrakar took these photos. Others deaths have gone undocumented.

Chitrakar says many of the women he spoke with accept the practice as part of their lives, but would give it up instantly if everyone else in the village stopped, too. Nepal's supreme court declared chaupadi illegal in 2005.

A pressure to conform keeps this tradition entrenched in some cultures, particularly in villages hidden in the Himalayas and far away from modern Nepali cities.

Rupa Chand Shah, pictured, grew up missing school during her period. "One of her life's regrets was that she could not attend her young brother's wedding because she was menstruating," Chitrakar recalls.

Shah, 32, works as a schoolteacher and aims to abolish the tradition. She teaches an awareness class at a nearby school and boasts that her students come to class during their cycle.

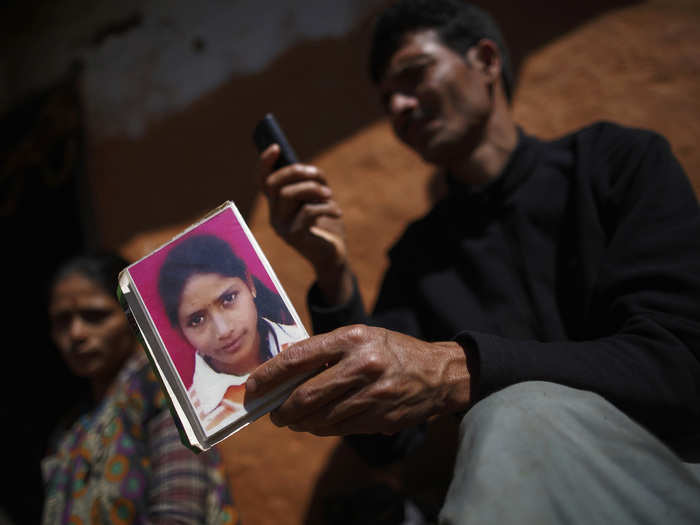

For others, the lesson is learned too late. Here, Yagraj Bhul and his wife, Ishwora Bhul, stand outside their house, not far from the abandoned shed where their 15-year-old daughter died practicing chaupadi a year ago.

Since their daughter's death, not a single female in the family has gone to a shed during menstruation. "I used to love her a lot but she left us," the girl's grandmother says, "and taught us a lesson that chaupadi is not a good practice."

Popular Right Now

Advertisement