I spent the day working in a 2-star Michelin restaurant where dinner costs $300. I sliced sashimi, made dessert, and was shocked by the kitchen's calm vibe.

Anneta Konstantinides

- I spent the day shadowing chef Michael Cimarusti and his staff at Providence, a two-star Michelin restaurant.

- I helped make chocolate, sliced sashimi, and spoke to everyone from the prep cooks to head chefs.

As someone who grew up loving food and cooking shows, I always wondered what it'd be like to work in a kitchen. And, lucky for me, the two-star Michelin restaurant Providence opened its doors.

The restaurant business — and the people who work in it — has long been a fruitful pop culture subject, especially in recent years. "The Menu" satirized the world of fine dining, "The Bear" peeled back the brutal pressures of culinary perfection, and Gordon Ramsay launched a successful reality TV career by portraying an intense, foul-mouthed chef on "Hell's Kitchen."

It's a world that's always captivated me, especially as someone who barely knew how to cook just a few years ago. As my skills slowly began to improve during the pandemic, I found myself wondering what it'd be like to spend a day among some of the world's most talented chefs.

And I got to do just that with chef Michael Cimarusti and his incredible team at Providence in Los Angeles, California.

There are only four restaurants in California with two Michelin stars. Providence is one of them.

Providence — which is owned by Cimarusti, his wife (and Providence pastry chef) Crisi Echiverri, and Donato Poto, the restaurant's general manager — has held onto its two Michelin stars for over a decade.

The Hollywood spot has won much praise, and plenty of fans, for its commitment to sustainable seafood in the world of fine dining.

Seafood was a natural fit for Cimarusti, who told me: "Before I was ever a cook, I was a fisherman."

"I fished every day of my life when I was a kid," he said. "We had a little pond a half-mile from my house that I'd go to every day after school."

After turning his attention to cooking, Cimarusti worked his way into some of the world's most famous kitchens — including Wolfgang Puck's Spago in LA and the three-star Michelin restaurant Arpège in Paris. Cimarusti returned to California to work at the famous Water Grill in Santa Monica, where he spent seven years before opening Providence's doors in 2005. Along with him came Tristan Aitchison, who has been the restaurant's chef de cuisine since day one.

After putting on my chef whites, I was ready to start my shift at Providence.

I walked in around noon and was surprised to find that the kitchen was still peaceful. But I quickly learned that many people had already been working for hours.

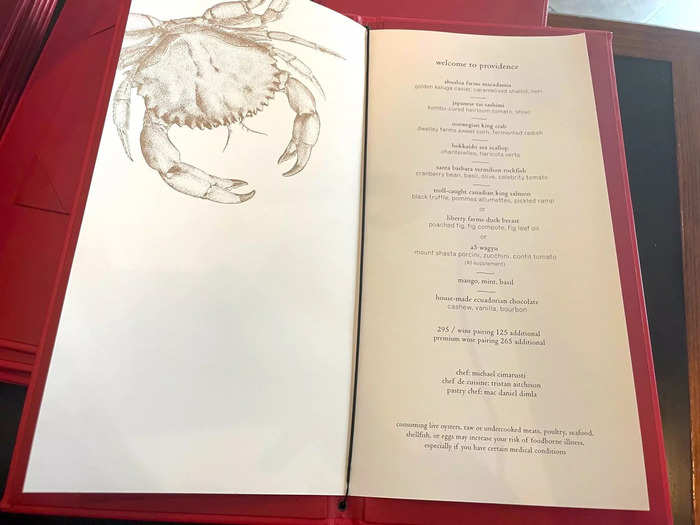

Providence is only open for dinner and features a set eight-course menu (a vegetarian option is also offered) that starts at $295 per person. The restaurant is sold out every night, with reservations being booked up weeks or months in advance.

Cimarusti explained that shifts at Providence are broken into a.m. and p.m. The prep cooks and fishmongers come in at 7:30 a.m. and leave around 4:30 to 5 p.m. The rest of the staff — including the line cooks and sous-chefs — come in at 2 p.m. and leave around midnight or sooner, depending on the night. Cimarusti and Aitchison both typically come in around 10 a.m. and usually don't leave the restaurant until around 11 p.m.

The days are long, but Aitchison told me the hard work is worth going to the kitchen every day and "being able to use my hands to create something."

"It might not always make it onto the menu, but every day is different, so it sparks a lot of opportunities to try something new," he added. "I like the unknown of what each day is going to provide."

While the kitchen slowly comes to life, Cimarusti and Aitchison sit down to discuss any changes to the menu and what they can improve from the night before.

The dishes at Providence change frequently, and Cimarusti told me the kitchen practices each dish "hundreds of times over the course of several weeks" before it ends up on the menu.

"Once we get to a point where the dish is just perfect and everyone gets it, that's when it has to come off," he said.

As I walked around the kitchen, I spotted a handwritten list with the names of guests coming that night. It detailed tables with larger parties, as well as any notable restrictions ("allergic to eggplant," "no coriander") so the cooks could prepare well in advance.

The list also noted returning guests and the date they were last at Providence. Cimarusti told me Providence has one guest who comes every week (and once requested an eight-course dinner he could take on his private plane).

"We try to do a different menu for him every week," Cimarusti said. "It's an incubator. A lot of those dishes that we cook for him turn into menu items at a certain point."

I first worked with Mac Daniel Dimla, a 27-year-old pastry prodigy who leads Providence's zero-waste chocolate program.

Dimla led me to a temperature-controlled room upstairs, where I was immediately greeted with the delicious scent of chocolate.

Every month, Providence receives 100 pounds of raw cacao beans that have been sourced from Hawaii, Dimla told me. Each and every bean is inspected, processed, and roasted by the four-person pastry team.

All the restaurant's chocolate is made in-house and nothing goes to waste. Dimla turns the leftover cacao husks into chocolate tea.

After filling a piping bag with fresh chocolate, Dimla showed me how to fill the molds.

Dimla expertly squeezed the bag as he went down the line of molds and, within seconds, his tray glistened with the sesame-praline chocolate ganache. It was almost soothing to watch.

I took my place next to Dimla and tried to mimic his technique, filling one mold in the time it took him to do 20. He waited patiently as I tried to catch up — squeezing chocolate was way harder than it looked.

Then I returned to the kitchen to watch the prep cooks.

I gazed in wonder as one of the cooks kneaded balls of dough, skillfully folding, tucking, and rolling each one along the flour-covered stainless steel tabletop.

Cimarusti explained that she was prepping the dough for the following night's dinner service. Each ball sits overnight and slowly proofs under refrigeration.

As I visited various cooks at their stations, I was surprised to learn that cooking was a second career for a number of them. One started culinary school after years in fashion, while another had switched from being a pharmacist.

"I started at the bottom, bottom, bottom," one sous-chef told me. "It's similar to any industry where, once you master that station or level, you're like, 'OK, I'm ready to progress to the next thing.'"

Meanwhile, on Providence's rooftop garden, the bees were also working hard.

Providence has an on-site rooftop garden, where the staff grows everything from wasabi arugula and strawberry spinach to Japanese mustard greens and Greek basil. The garden uses recycled water, including melted ice from the kitchen, and provides many of the fresh ingredients seen in the restaurant's famous cocktails and dishes.

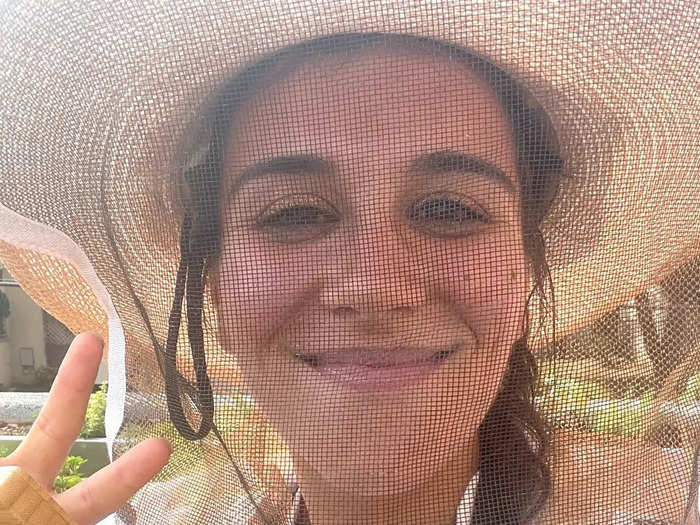

After putting on a protective hat and veil, I got to check out Providence's two beehives, which spin fresh honey for the restaurant on-site.

I was ready for a drink, so I swung by Providence's bar.

A true shift in a Michelin-star kitchen likely wouldn't include luxury cocktails, but I wanted to spend some time chatting with Kim Stodel, Providence's bar director.

Stodel previously showed me how he made Providence's famous $100 margarita, which is part of his tableside cocktail program that features one-of-a-kind drinks.

Providence's bar is as committed to sustainability as the kitchen, and Stodel is constantly breathing new life into leftover ingredients. The shells of snap peas are seasoned with citrus and sugar to flavor some gin. The pulp of a raspberry is turned into powder that can be dusted over a passion-fruit mocktail.

Then it was time to check out Providence's wine cellar.

David Osenbach, a level three sommelier and Providence's wine director, creates the wine pairings that can be ordered with the tasting menu. "This is where the magic happens," he declared as we walked into the chilly 55-degree room, where wine bottles filled nearly every inch of space.

The wine pairing at Providence sometimes changes more than the menu, and Osenbach told me he likes to pick bottles that people normally wouldn't buy for themselves.

"Sometimes that throws people off a little bit," he said. "They're like, 'I've never heard of any of these wines,' and I'm like, 'That's the point!'"

Osenbach always aims to create a pairing with a variety of grapes and regions, although his "desert island wine," as he calls it, will always be Riesling.

"It's a good go-to," he said. "And if I'm actually stranded on a desert island, it'll probably pair nicely if I'm foraging coconuts and catching fish with a spear."

It was 3 p.m. when I headed back into the kitchen. The staff was in full swing, and watching everyone prepare dinner was a feast for the senses.

You could hear the satisfying sizzle of the pans, the clink of spoons hitting glass, the clang of pots on the stove, and fridge doors shutting close. Fresh mint filled the air as a prep cook picked and plucked its leaves. The bright colors of a mango compote smiled back at me.

"I would say 3 in the afternoon is the busiest," one sous-chef told me. "Everyone is really cranking at that hour and there's lots to get done."

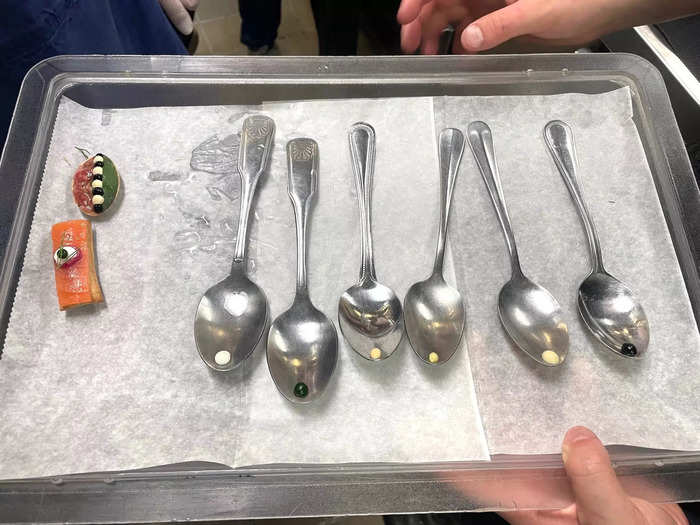

I made my way to the garde manger station, where the night's first bites are made.

The amuse-bouches are tiny, but I was amazed to see just how much work went into building each one.

A cook explained how the lightly-steamed oysters he was about to shuck were going to be chopped and blended until they were super smooth. He'd then add some lemon juice and Tabasco to make the oyster mayonnaise. A small dot of that mayonnaise would then be piped on a perfect cube of A5 Wagyu.

I watched as Cimarusti tested every sauce that goes on the small bites.

There's an entire station dedicated to sauces, and Cimarusti conducts a nightly sauce test for each dish. I watched as a tray of spoons was brought to him with tiny dots of different sauces on the tip of each one. Cimarusti went through the tray in rapid succession, his taste buds immediately picking up which sauce was off.

"All these sauces are the building blocks of those two little canapés I ate," Cimarusti explained. "So if the canapé is off, you can go back to those little things and see if this purée is a little too heavy or that purée is a little too salty. Tasting the elements and the finished products, you get a sense if it's ready."

When I asked Cimarusti how he could discern what was missing so quickly, he said it all came down to developing your palate — something he frequently reminds his kitchen is incredibly important.

It's this kind of impeccable precision, and the way Cimarusti and Aitchison teach it, that draws cooks to Providence.

"Everything is brand-new, and it feels energizing for sure," one cook told me. "People are coming in and paying $300 right when they sit down. So everything has to be perfect, and I know everyone working here has the same mindset as I do — we want to achieve excellence."

"Big egos do not fly here," they added. "You've got to be humble, and you've got to be willing to learn."

And Cimarusti credits the younger cooks with helping to keep him fresh and innovative.

"I'm an old dude surrounded by kids and that's inspiring in itself, to be around younger people," he said. "I'm always learning from them and being inspired by them."

Cimarusti even took the time to teach me how to properly slice sashimi.

We headed to the fish box, where Cimarusti showed me a gorgeous wild Japanese Tai snapper shipped straight from Tokyo. After throwing on some Grateful Dead (live concert albums only, according to Cimarusti) on the speaker, it was time to get slicing.

I attempted to follow Cimarusti's direction, placing my hand at the heel of the knife. But as I drew the knife back, I could immediately see I had screwed up.

"No, no, see — you're mushing," Cimarusti told me.

"Butchering, whether it's meat or fish, it's not a skill that comes easily," Cimarusti assured me. "You really need, like, years and years of practice. Even a month ago, I wasn't as good."

If at first you don't succeed, slice and slice again. I picked up the knife, and Cimarusti demonstrated the proper technique and finger placement again. I drew the knife back, reminding myself to let the blade do all the work, and voila! A thin, translucent slice of sashimi appeared.

"Pretty good," Cimarusti told me, taking the slice and placing it with the others. "Somebody's going to eat that tonight."

I couldn't help but do a little victory dance. Someone was going to eat a piece of sashimi I sliced at a two-star Michelin restaurant! Is this how Gordon Ramsay feels every night?

As the start of dinner service neared, Cimarusti announced it was time for the crew meal.

Anyone who has seen "The Bear" — or the dozens of videos replicating its famous spaghetti — knows about the crew meal, which is the nightly dinner that the kitchen shares before service begins.

At Providence, the kitchen staff rotates who cooks the crew meal every night. The day that I was shadowing the meal featured some juicy roasted chicken, creamy scalloped potatoes, rice, fresh greens, and a few macaroons. Our quart-sized deli cups (yes, they really do drink out of them) were filled to the brim with delicious juice.

We all sat around a table in the dining room and I listened as the staff swapped stories about mutual friends and people who had worked in the kitchen. Crew meal, I realized, wasn't just about fueling the staff before a busy night. It was about creating connections through food — which is, after all, how they all fell in love with it in the first place.

"Some of the best memories of my life were forged at tables at restaurants like this," Cimarusti told me. "Long before I ever cooked professionally, when I was a kid with my parents."

Then the front-of-house staff gathered for their nightly meeting.

The servers listened intently as Osenbach explained the wines they'd be serving that night and poured glasses for them to try.

Then Cimarusti took over to discuss which variety of oysters and caviar were available as add-ons to the tasting menu.

"The menu is pretty much unchanged from yesterday, but look for the duck to be changing in the next couple of days," he told them.

It was time to go back into the kitchen, where everything felt calm but swift.

As I looked around the kitchen, now mere minutes from dinner service, there were about 50 things going on at once. One cook was expertly dicing shallots, while another was slicking black truffles down a mandoline. A prep cook was picking herbs, and another was sorting berries.

"Twenty minutes guys, let's think about wrapping up," Aitchison yelled.

"Yeeeeah!" the kitchen staff all yelled back in response.

I spotted the chocolate bars I had helped mold just hours before, and watched as Aitchison transformed the sashimi I sliced into a stunning rose.

Being able to use ingredients like wild Japanese Tai snapper every day is why Aitchison wanted to work in fine dining in the first place, he told me.

"Having access to some of the best ingredients in the world such as fish flown in from Japan or truffles, I consider myself lucky," he said. "I get to work with high-end ingredients every day. And at the end of the day, we just want to give the ingredients the most respect we can."

Looking at the beautiful dish before me, I thought about how many people helped bring it to life.

Whether it's dicing the shallots, picking the mint, or butchering the fish, everyone in the kitchen is contributing to the perfection of each dish. And they're all motivated by the same thing: creating an unforgettable dining experience.

"We have so many people that have come here ever since we opened, that have been our guests all along," Cimarusti said. "And I feel like we have a greater responsibility to them too to keep the restaurant evolving, keep the restaurant fresh, and make sure it's at least as good as it was the last time — and hopefully better."

As my shift at Providence came to an end, I was surprised by how energized I'd felt by the whole day — and how much I've missed the kitchen since.

My day at Providence had been so inspiring, both as a food lover and a food writer. Watching the staff work together to create such incredible dishes, I finally understood what people meant by feeling a rush in the kitchen. It had felt like a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

So it's probably no surprise that on a recent weekend away with friends, when someone asked what our job would be if we had to choose a new profession, I instantly had my answer.

"A chef," I proudly said.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement