Stunning aerial photos show the collision of man-made waterways and mines with actual nature

Heilner discovered mesmerizing potash mines in Utah while on a cross-country commercial flight. They immediately caught his eye and he knew he had to come back to photograph them.

Potash is a high potassium compound that's a major ingredient in fertilizers used by farmers across North America. "If you ate any vegetables today, and they were grown in America, there’s a decent chance that potash from this mine helped grow it," says Heilner.

Potash is produced in desert regions where inland seas or lakes have dried out. As the water evaporates, it leaves behind potassium salt deposits. Over time, sediment buries these deposits and they become potash ore, which is soluble. These mines pump the potash all the way to the surface of the water held in these "evaporation pools."

But the colors of the water aren't produced naturally by the potash. Dyes are used to help speed up the crystallization process that's necessary for the potash to be used in fertilizer. About 60% of US potash production happens at this mine near Mohab, Utah.

Another formation that Heilner found intriguing is the world's largest artificial archipelago, Palm Jumeirah, located off the coast of Dubai.

Construction began on these residences in 2001. By 2006, the homes of Palm Jumeirah were ready to be occupied. The three separate archipelagos that were built have added 320 miles to the coast of Dubai.

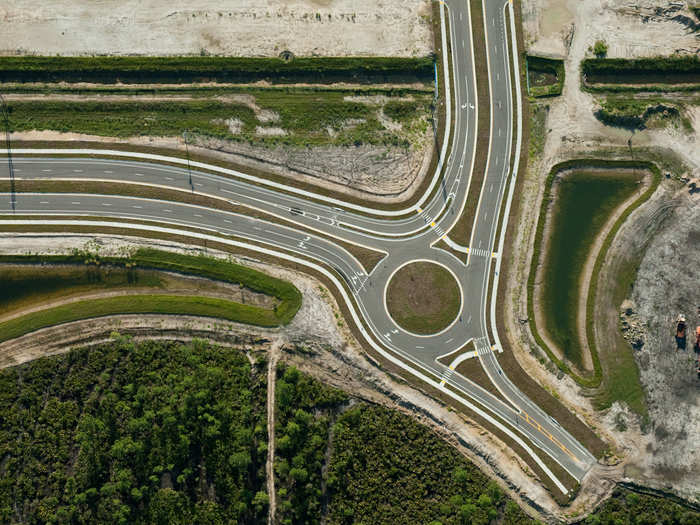

Another site of interest to Heilner was Cape Coral, Florida. Developed in 1957, the land was scouted and purchased by two brothers from Baltimore, Leonard and Jack Rosen.

Prior to the 2008 recession, Cape Coral was one of the fastest growing developments in America.

When Heilner photographed Cape Coral in 2009, construction on many of the new housing developments in the area had halted.

The photographs paint a picture of a fast and slow economy. "When you look at the pictures, you’ll see that some show very densely built areas, and those are the older homes, built in the '50s, '60s, and '70s, and the images that show a lot of open spaces developed in the '90s and '00s and were stalled — probably permanently,” says Heilner.

In 2010, Heilner made it his mission to visually pinpoint and photograph "the end of the Mississippi River."

He quickly discovered that you simply can't do that, "because a flood delta by definition just dissipates out into the ocean into nothing." What his photos did uncover is the location of an oil company's helicopter operations, as well as other facilities. "You’ve got this huge lay area of swamp with a couple oil facilities in the middle of it,” he says.

Venice, Louisiana (pictured below), is one of the last places you can drive to in the Delta.

Heilner says he's often asked about the environmental stance of his photos. His response: "If all information is on the table, people make good decisions. Most of the bad decisions that we make are engineered by interests who alter our understanding — that make things seem less clear."

For Heilner, these images are adding information to the conversation, and into the public's collective consciousness. "I'm much more interested in the viewers coming to their own conclusions organically rather than me just saying them outright."

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement