10 iconic buildings from the architect behind America's most stunning mid-century modern structures

Gateway Arch, St. Louis, Missouri

MIT chapel, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Eric Saarinen, who is also the director of photography for the project, was estranged from his father, who left the family to marry another woman. The documentary is both a visual exploration of Eero Saarinen’s career and a glimpse into the architect’s personal life.

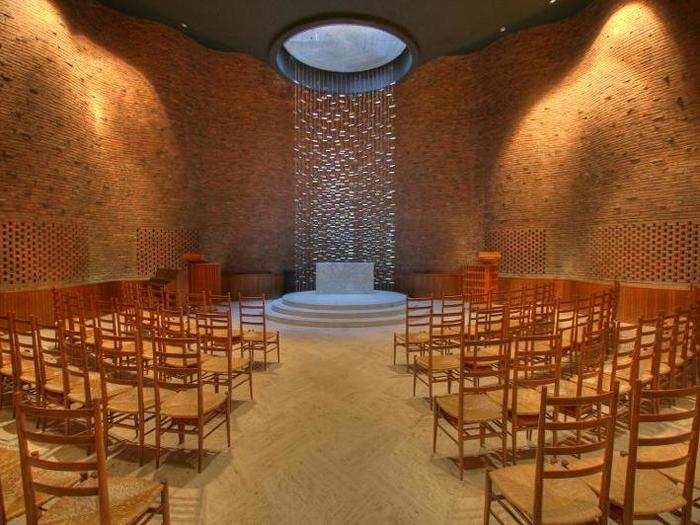

In the film, the team visits MIT’s nondenominational chapel, which Saarinen completed in 1955. Natural light flows from a circular skylight, sending a bright beam onto the altar. A sculpture by Harry Bertoia now hangs from that opening, creating a cascade of reflecting light.

Though the exterior of the chapel is smooth and round, the walls inside undulate in a wave-like pattern. Rather than following a specific religious tradition, the space encourages silent reflection.

Dulles International Airport, Dulles, Virginia

Rosen said he found one of the most striking things about Saarinen’s work to be the contrast between the scales of his various works. One of his largest designs was for Dulles Airport, where he created a massive, open terminal the length of three football fields.

“The impact would be this huge difference between one of the largest interiors I’ve ever seen and the really intimate scale of the chapel at MIT,” he says of his own takeaways from the film.

TWA Terminal, New York, New York

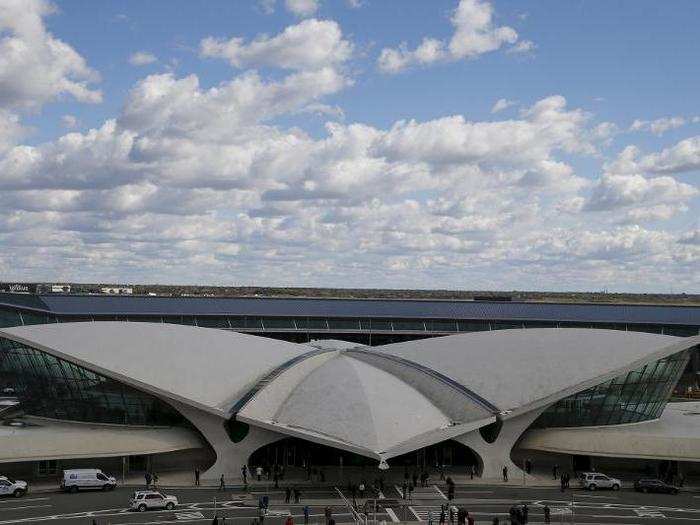

Saarinen’s most famous airport design, however, is the now empty TWA terminal at New York’s JFK Airport. According to the documentary, Saarinen’s design for the structure was constantly in flux and so hard to draw that the team assembled a massive model of it before ever putting it on paper. Saarinen would literally put himself in the middle, poking his head in and moving pieces around, to finalize his concept.

Even when the final design was put on paper and approved by the client, Saarinen decided it wasn’t right and quite literally went back to the drawing board.

The stunning design evokes the marvel and excitement of flight and travel, with arched lines and suspended platforms and bridges on all sides. Though the space is no longer in use as an airport due to modern security requirements, it is slated to be turned into a hotel in the near future, with the open terminal interior preserved.

Rosen says the unique airport design airport is an example of Saarinen’s constant innovation

“He could have this huge success with TWA, but never went back to that idea again,” he says.

David S. Ingalls Rink, New Haven, Connecticut

Yale’s hockey stadium is sometimes known as the “Yale whale” because of its organic, animal-like curves.

Saarinen himself was a Yale graduate, and according to the documentary, he sent several employees to scout other hockey rinks before starting on the design for one at his alma mater. The staff were instructed to observe and report back about the best rinks, but they collectively decided that comparable arenas were poorly designed across the board.

To differentiate his, Saarinen used an arched concrete backbone with cables descending from the sides to hold up the roof.

General Motors Technical Center, Warren, Michigan

Saarinen designed headquarters and research centers for quite a few major companies, including IBM and Bell Labs. That work started with the General Motors Technical Center, where the building’s modern facade — a curtain of glass — represented the country’s post WWII optimism about the potential of technical progress and corporate America.

Glass had never been used at that scale before, though it has since become a standard in business centers.

“That led the way to five decades of glass and steel buildings,” Rosen explains.

Kresge Auditorium, MIT, Cambridge, Massachusetts

According to the documentary, Saarinen conceived the design for MIT’s famous auditorium while eating a grapefruit. The curved shape comes to three points in the same way an eighth of a grapefruit does if turned upside down, with the peel facing the sky.

“When you look at these things today, they don’t seem that unique unless you understand that they’re all 50 or 60 years old, and basically the first time anyone tried to do something with curved concrete,” Rosen explains of the structure.

John Deere World Headquarters, Moline, Illinois

“In interviewing architecture critics in the film, I would say, ‘What’s your favorite Saarinen building?’ and invariably they would say John Deere," Rosen says.

Though Saarinen’s design for the John Deere headquarters might not look as original as many of his other structures, no other buildings at the time boasted anything similar to the rusted steel, exposed structural beams and massive indoor atrium that Saarinen created.

The documentary says the building was built with nearly double the amount of steel than would be used in a normal office building. Its entrance is a giant showroom with John Deere tractors and machines on display, and glass walls look out on the surrounding greenery.

Vivian Beaumont Theater, New York, New York

Saarinen died in 1961 at only 51, cutting short what might have become an even more prolific career. At the time, his final drawings for the Vivian Beaumont Theatre in New York City’s Lincoln Center were just getting approved. The structure wasn’t completed until four years after his death. It’s now considered the only Broadway theater outside New York City’s theater district.

Like other Saarinen buildings, it easily differentiates itself from other comparable structures — it was the first theater in the world to have a computerized lighting system, and its stage is three times the size of other Broadway theaters at 10,000 square feet. A new blackbox theater was added on the roof and unveiled in 2010.

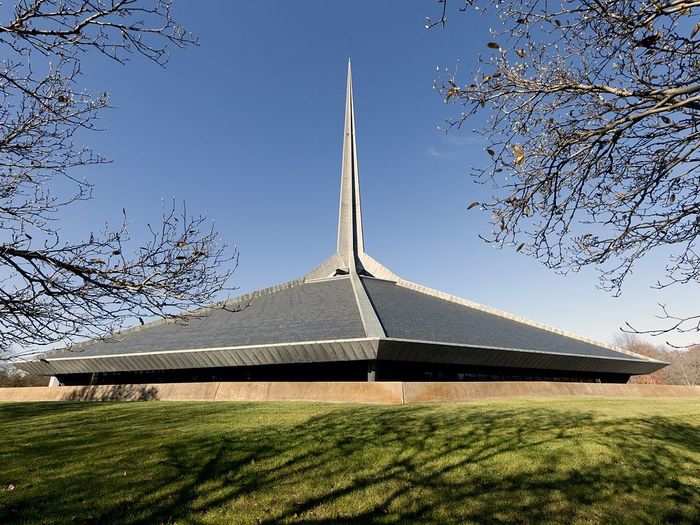

North Christian Church, Columbus, Indiana

The geometric church building was the last one Saarinen ever designed — he submitted the final version of his plan only a month before he died. The church is hexagonal, with a tall spire that rises 192 feet and is topped with a small, gold cross. On the inside, the spire lets in natural light, which is complemented by lights that border the sanctuary’s edges. Unlike traditional spaces of worship, the altar stands in the middle, with pews surrounding it on all sides.

The other, less religious parts of the church — bathrooms, kitchen, etc. — are buried underground, leaving only the sanctuary space immediately visible to visitors.

Rosen says one of the most unanticipated and moving things about making the film was watching Eric Saarinen discover the spaces his father created for the first time. By the end of the documentary, Eric shows a new appreciation for his father’s genius, driven especially by the beauty of intimate spaces like the church.

“The added surprise was how personal it all became,” Rosen says of the process. “He’s just our director of photography, who wound up being the center of the whole film.”

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement