- Home

- tech

- Facebook just lost a $500 million Law & Ordersuit - here's what's going on

- Facebook just lost a $500 million lawsuit - here's what's going on

Facebook just lost a $500 million lawsuit - here's what's going on

August 2013: Oculus VR, a startup working on a virtual reality headset called the Rift, hires "Doom" creator John Carmack of id Software as its chief technology officer.

Carmack got the prototype headset from Palmer Luckey, the impossibly young face of the Oculus Rift. He was repeatedly held up as the genius inventor behind the headset.

So the story goes: Palmer Luckey was working on the Oculus Rift headset's earliest prototypes from his parents' house. Luckey was a member of several forums dedicated to the world of 3D and, eventually, virtual reality. He was a part of the "mod" community, which is notorious for taking existing hardware and modifying it into something new — a portable Xbox 360, or a GameBoy that plays Super Nintendo games, for instance.

On the journey from ski-goggle prototype to something sellable, Carmack — an idol of Luckey's and, apparently, a member of the same VR forum — got in touch and asked to be sent a prototype. Wired catalogued the exchange in a 2014 story timed to publish soon after the Facebook acquisition:

"Carmack private-messaged him. Would Palmer consider sending him a loaner unit? Palmer, who idolized Carmack, shipped it off to Texas immediately — 'no NDAs, no signing anything,' Carmack says. 'It was one of two prototypes that he had.'

Carmack got to work on the machine, hot-gluing a motion sensor to it and duct-taping on a ski-goggle strap. But his greatest contribution came in the code he wrote for it. The Rift’s biggest selling point was its 90-degree field of view, which Luckey accomplished by slapping a cheap magnifying lens on the display. The problem was, that lens distorted the image underneath, making it warped and uneven. So Carmack coded a version of 'Doom 3' that pre-distorted the image, counteracting the effects of the magnifying lens and making the picture appear correct to the viewer. The result was a completely immersive gaming experience, the kind that would otherwise require $10,000 in high-end optics."

March 2014: Facebook buys Oculus VR

In March 2014, Facebook announced the acquisition of Oculus VR — an independent startup. Unlike Instagram or Whatsapp, it was less obvious why Facebook would buy a fledgling startup that was, at the time, creating the first major VR headset since the technology faded from popularity in the mid-'90s.

Zuckerberg justified the purchase as such:

"History suggests that there will be more platforms to come. Today's acquisition is a long-term bet on the future of computing."

In Zuckerberg's eyes, the folks at Oculus VR were creating "the future," and he wanted Facebook to be integral in building that vision of the future.

May 2014: Zenimax Media sues Oculus VR, now owned by Facebook

Just two months after Facebook announced its acquisition of Oculus VR, Zenimax announced its intent to sue Oculus and, by extension, Facebook.

At the heart of the suit was the contention that John Carmack allegedly took company secrets with him when he left id Software (owned by Zenimax) for Oculus (owned by Facebook). Before filing suit, Zenimax lawyers contacted Oculus VR with those claims. Zenimax provided media the following statement at the time:

"Zenimax confirms it recently sent formal notice of its legal rights to Oculus concerning its ownership of key technology used by Oculus to develop and market the Oculus Rift. Zenimax's technology may not be licensed, transferred or sold without Zenimax Media's approval. Zenimax's intellectual property rights arise by reason of extensive VR research and development works done over a number of years by John Carmack while a Zenimax employee, and others. Zenimax provided necessary VR technology and other valuable assistance to Palmer Luckey and other Oculus employees in 2012 and 2013 to make the Oculus Rift a viable VR product, superior to other VR market offerings.

The proprietary technology and know-how Mr. Carmack developed when he was a Zenimax employee, and used by Oculus, are owned by Zenimax. Well before the Facebook transaction was announced, Mr. Luckey acknowledged in writing Zenimax's legal ownership of this intellectual property. It was further agreed that Mr. Luckey would not disclose this technology to third persons without approval. Oculus has used and exploited Zenimax's technology and intellectual property without authorization, compensation or credit to Zenimax. Zenimax and Oculus previously attempted to reach an agreement whereby Zenimax would be compensated for its intellectual property through equity ownership in Oculus but were unable to reach a satisfactory resolution. Zenimax believes it is necessary to address these matters now and will take the necessary action to protect its interests."

A war of words ensued. Here's what Oculus/Facebook had to say at the time:

As you might imagine, Facebook and Oculus didn't throw up their hands and say, "You got us!"

Instead, the following statement was issued to the press:

"It's unfortunate, but when there's this type of transaction, people come out of the woodwork with ridiculous and absurd claims. We intend to vigorously defend Oculus and its investors to the fullest extent."

More directly, Carmack took to Twitter to defend the claims being made against him. He stated, "No work I have ever done has been patented. Zenimax owns the code that I wrote, but they don't own VR."

Put a pin in that Twitter statement from Carmack — we'll revisit it below.

And here's what Zenimax had to say at the time:

Zenimax, being a public company, issued a press release announcing the lawsuit.

In the release, Zenimax repeats the claim that Carmack took trade secrets with him to Oculus, and that the technology at the core of the Rift headset was developed by Carmack for Zenimax during his employment. The company also explains why it pursued a lawsuit rather than another form of resolution:

"All efforts by Zenimax to resolve this matter amicably have been unsuccessful. Oculus has recently issued a public statement remarkably claiming that 'Zenimax has never contributed IP or technology to Oculus.' Meanwhile, Luckey has held himself out to the public as the visionary developer of virtual reality technology, when in fact the key technology Luckey used to establish Oculus was developed by Zenimax."

Both companies went silent until January 2017, when the case went to court.

Of note, Wired's 2014 story spells out much of what's being alleged in the suit. Carmack freely admits to having worked on code for the Oculus Rift prior to being hired by Oculus VR/Facebook in 2013. Though it's not clear in the story, the presumption is that Carmack did this work in his free time — not while he was on the clock at Zenimax.

Zenimax, however, contends that the work Carmack did that was integral to the Rift was done while on the clock at Zenimax. More specifically, Zenimax claims that Carmack took work beyond his own. "Carmack and other Zenimax employees conducted that research at Zenimax offices, on Zenimax computers, and using Zenimax resources," the company said in 2014.

Things get especially muddy when it comes to who did what, where, and when. It's clear that Carmack was exploring VR in his time outside of the office. It's also clear that Zenimax was working on its own research into VR internally, led by Carmack. There was even an agreement between Zenimax and Oculus to produce a VR version of the Zenimax-published game "Doom 3" for use in the Oculus Rift. That deal eventually fell apart.

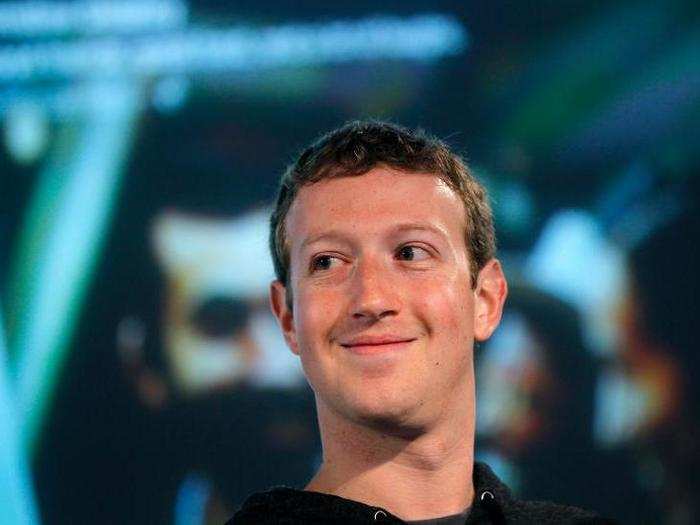

Major names at Facebook, including Mark Zuckerberg, took the stand.

“We are highly confident that Oculus products are built on Oculus technology. The idea that Oculus products are based on someone else’s technology is just wrong," Zuckerberg said in sworn testimony during the trial.

When asked about the progress that Oculus has made toward the ubiquitous VR future that Zuckerberg envisions, he admitted it's been slow going so far. "These things end up being more complex than you think up front. If anything, we may have to invest even more money to get to the goals we had than we had thought up front."

Oculus co-founder Palmer Luckey also spoke under oath — he disappeared from the public eye following revelations about his political ties in September 2016:

For Luckey's part in the trial, he was primarily on the stand defending the origin story of the Rift. He continues to contend that much of the original work on the Rift prototype was done in his parents' home, by him, ahead of the E3 2012 trade show in mid-2012.

“I didn’t take confidential code," Bloomberg reported him saying during the trial. "I ran it and demonstrated it through the headset. It is not true I took the code."

To be completely clear, Luckey contends that — while he used code in the Rift that was proprietary to Zenimax, provided to him by Carmack — he didn't take it for use in the final version. At the heart of this argument is the concept of how copyright law applies to code written by programmers.

In the process, Facebook revealed it paid even more than previously thought for Oculus VR: $3 billion including "employee retention packages and goal targets." Whoa.

Also revealed during the trial, the original asking price for Oculus VR was $4 billion — Zuckerberg talked the company down to $2 billion... plus another $700 million "in compensation to retain important Oculus team members" and $300 million "in pay for hitting certain milestones," the New York Times reports.

For those of you playing along at home, that means Facebook purchased Oculus VR for $3 billion total — not the $2 billion that was reported in 2014. It's unclear if Oculus VR hit the milestones required for the additional $300 million payout; the entire Oculus VR executive team stayed on after Facebook acquired the company, so it's likely that the additional $700 million was paid out. It's entirely possible (likely, even!) that some of that money went directly to John Carmack, the CTO of Oculus, for retention.

In the end, the jury decided that Oculus wasn't guilty of stealing trade secrets.

Like so many cases in the legal system, the end to the Zenimax v Facebook trial is complex. A jury decided that Oculus wasn't guilty of stealing trade secrets.

"The heart of this case was about whether Oculus stole Zenimax's trade secrets, and the jury found decisively in our favor," an Oculus spokesperson told Business Insider.

The truth, however, is more complex.

While deciding Oculus was innocent, the jury also decided to award Zenimax $500 million for violations of non-disclosure agreements. Here's who's paying what:

The good news for Facebook/Oculus is that it wins the PR victory of being able to say it was found innocent in a jury trial. The bad news is that Facebook is shelling out another $300 million in payments to Zenimax, bringing the grand total Facebook has paid for Oculus up to $4.3 billion.

Here's the full breakdown:

- Oculus has to pay Zenimax $200 million for violating the non-disclouse agreement Oculus co-founder Palmer Luckey signed with Zenimax.

- Oculus has to pay Zenimax an additional $50 million for copyright infringement, and another $50 million for false designation.

- Former Oculus CEO Brendan Iribe will have to pay Zenimax $150 million for false designation.

- Oculus cofounder Palmer Luckey will have to pay Zenimax $50 million for false designation.

In case you're wondering what "false designation" is, it's the act of lying about an origin. In this sense, the jury concluded that former Oculus CEO Brendan Iribe and Oculus co-founder Palmer Luckey both lied about the origin story of the Oculus Rift.

But that's not all! Oculus is appealing the ruling, and Zenimax is promising to pursue an injunction against sales of the Rift.

As you might expect, the case may be over but the battle has just begun.

Lawyers from Oculus and Zenimax stated their intents to appeal the ruling and seek an injunction against the Rift headset (respectively).

Here's Oculus:

"We're obviously disappointed by a few other aspects of today's verdict, but we are undeterred. Oculus products are built with Oculus technology. Our commitment to the long-term success of VR remains the same, and the entire team will continue the work they've done since day one – developing VR technology that will transform the way people interact and communicate. We look forward to filing our appeal and eventually putting this litigation behind us."

And here's Zenimax:

"We are pleased with the jury’s award in this case. The award reflects the damage done to our clients as the result of the theft of their intellectual property. We believe that our clients' rights have been vindicated.

"We will consider what further steps we need to take to ensure there will be no ongoing use of our misappropriated technology, including by seeking an injunction to restrain Oculus and Facebook from their ongoing use of computer code that the jury found infringed Zenimax’s copyrights."

Popular Right Now

Advertisement