- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- The wild story behind Tour de Trump, the Trump-sponsored bike race that became one of the biggest cycling events in American history

The wild story behind Tour de Trump, the Trump-sponsored bike race that became one of the biggest cycling events in American history

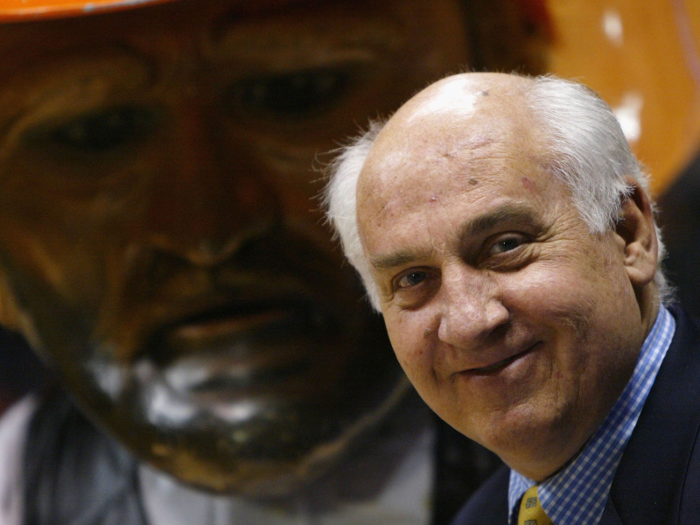

This strange tale began in a restaurant in Indianapolis in the summer of 1987, with a young reporter and a basketball announcer and entrepreneur named Billy Packer.

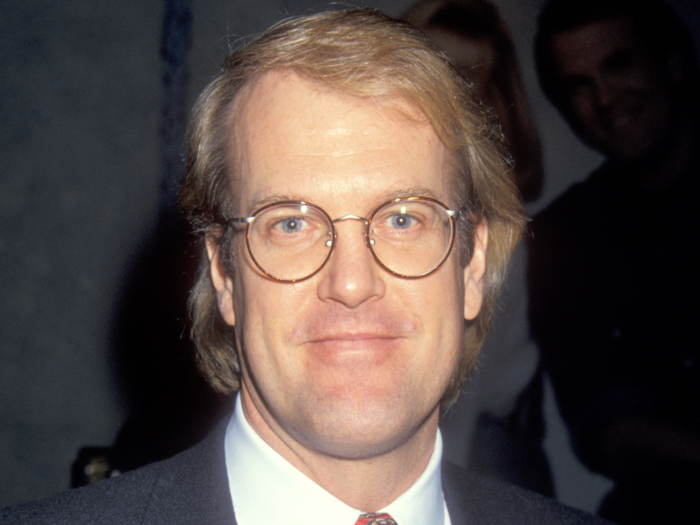

The young reporter was John Tesh, who had just covered the Tour de France.

Tesh — who would later become an Entertainment Tonight co-host — had just been in France covering the Tour de France. He told Packer he needed to do the same thing in the US, according to Politico.

Packer was hesitant. Cycling was far from his expertise.

He didn't know how to put air in tires, nor had he ever been to a cycling event, he told Politico. But he knew New Jersey's terrain, and he had investments in Atlantic City. He began to think there was something to the idea, he told the New York Times.

Packer originally wanted it to be called Tour de Jersey.

He planned for the race to go between Manhattan and Atlantic City, with a name that would be an on-the-nose nod to Tour de France, according to Politico. He approached executives at several Atlantic City casinos, who were intrigued, but didn't take it any further.

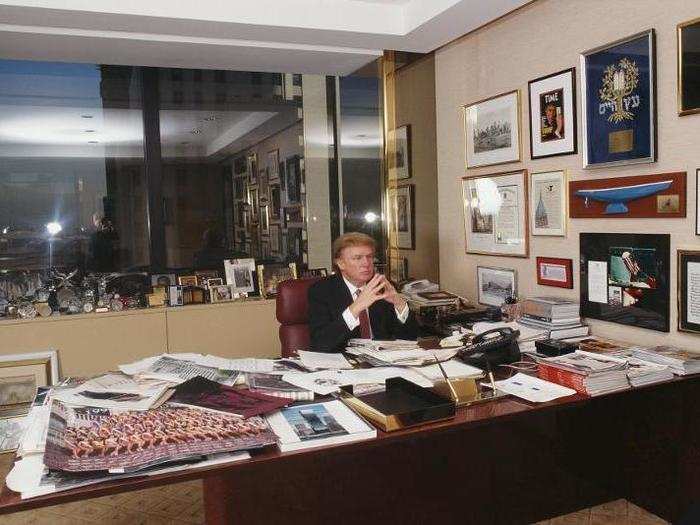

Then came billionaire Donald Trump.

Packer arranged to meet with him briefly in Trump Tower to pitch the idea.

Like Packer, Trump wasn't a cycling expert. He hadn't ridden a bike since he was about seven or eight years old.

Packer suggested Trump should offer his name to the event.

When Trump heard the idea he said he nearly fell out of his seat, according to The New York Times.

"I said, 'Are you kidding? I will get killed in the media if I use that name. You absolutely have to be kidding,'" Trump said.

But within 20 seconds, he had agreed. "It's so wild, it's got to work," he said, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Trump's lawyers then sent a "cease and desist letter" to the organizers of a small bike race called "Tour de Rump" in Aspen, Colorado.

They were worried that "Rump" sounded too much like "Trump" and threatened to sue if the name wasn't changed.

It could have been a David and Goliath situation, but the organizers didn't bow down, and Trump never followed up on the lawsuit threat.

The race began to take shape. Officials scoured 25,000 miles of America to plan the route of the 837-mile race.

Press releases were sent to journalists filled with big numbers: The race used 35,000 traffic cones, 40,000 feet of snow fence, 30,000 feet of rope, and 15,000 plastic ties.

Along with the big numbers came the big name.

When he was asked why it wasn't called the Tour of America, Trump said, according to Sports Illustrated, "We could, if we wanted to have a less successful race. If we wanted to down-scale it."

On a televised NBC News interview, he said his name had brought in "a lot of the racers."

Trump had grand ambitions before the race had even begun.

He told NBC News he wanted it to become the equivalent of the Tour de France.

"I can't say we're going to make it more. Although, in theory, you could say we have many more people so you, in theory, could make it more. But I would like to make this to be equivalent to the Tour de France," he said.

And he wasn't wrong. The race attracted quality cyclists.

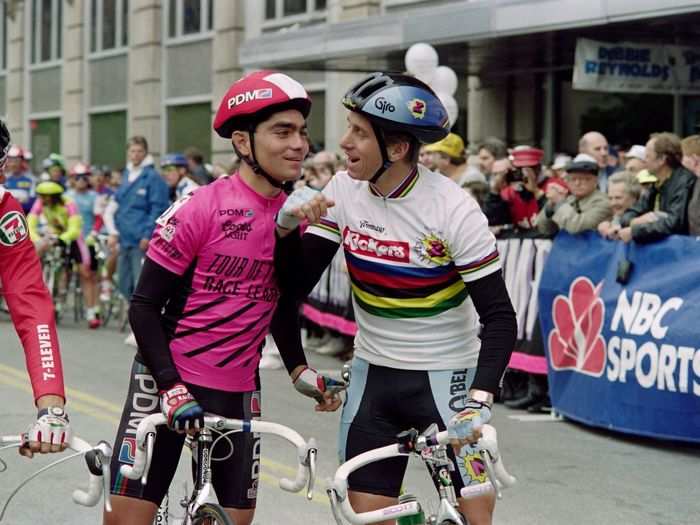

The race attracted 19 teams, eight of which were professional racers. Two of the biggest stars were Greg LeMond, at that time America's only Tour de France winner, and Olympic gold medalist cyclist Alexi Grewal.

The other 11 teams were amateur. One of the teams was sponsored by a brothel in Amsterdam, called Sauna Diana.

All in, 114 cyclists took part.

Meanwhile, Trump was learning some deep lessons about sportsmanship.

On the day before the race, Trump asked LeMond if it was possible to be friends with a competitor.

When LeMond said it was, Trump said, "I've never found that in life."

And it worked out financially, too.

Trump originally said he would guarantee $750,000 in funding for the race. But he told The New York Times the income generated even before it started covered "all of the costs and then some."

But his name wasn't always a bonus.

New York Gov. Mario Cuomo almost didn't attend the race, although he eventually relented and made an appearance.

Some cyclists told Packer some of the European cyclists said Trump's fame — by then, he had been involved in several scandalous relationships and business dealings — overshadowed the cycling.

New York City Mayor Ed Koch was a notable no-show.

According to Politico, Koch once called Trump "one of the great hucksters."

The race began on May 5, 1989.

In the first stage, which ran between Albany and New Paltz, cyclists took on a steep road known as the Devil's Kitchen, in the Catskills, which rose from 300 feet to 1840 feet above sea level over a two-mile stretch.

One of the tour directors told Sports Illustrated that it was so steep, when he took journalists to see it, they couldn't get the bus up the road.

At the end of the first legs, cyclists were greeted by protesters, not fans.

Even before he ran for president in 2016 that demonized immigrants, Trump was controversial. In the 1980s, some viewed him as a symbol of greed. Protesters held signs that read: "Trump = Lord of the Flies," or "The Art of the Deal = The Rich Get Richer," as well as "fight Trumpism."

Stage two began in New York City, where crowds were sparse. Cyclists rode for 123 miles through New Jersey and finished in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

The race's frontrunners soon became clear.

In the lead were professional teams 7-Eleven and Panasonic-Isostar. Cyclist Eric Vanderaerden, who was part of Panasonic-Isostar, was in the top three at the end of eight stages, behind Norway's Otto Lauritzen and Netherland's Henk Lubberding.

Despite his position, Vanderaerden wasn't allowed to tour Trump's 280-foot yacht, called "Trump Princess.

His manager insisted he rest up before the last race.

The rest of the race went through Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, before reaching Atlantic City, New Jersey.

According to Politico, these stages weren't as controversial.

The lack of drama might have gotten to Trump. At the end of the ninth leg, he told a journalist it wasn't a "legendary race in its first year."

The final leg began and ended at the Trump Plaza Hotel, in Atlantic City.

This was a historical spot, according to the Chicago Tribune, where Lyndon Johnson was nominated for president in 1964, and where Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party protesters once camped.

Unfortunately, Vanderaerden's rest proved futile.

The final leg of the race was mired in a minor controversy after he took a wrong turn off the course while following one of the official motorbikes.

By the time he realized and returned to the track, it was too late.

Lauritzen, a 32-year-old from Norway, won the race.

He was awarded a $50,000 check.

LeMond, who had been recovering from a series of injuries and was ill at the beginning of the tour, did not finish near the top.

At the end of the race, when the last cyclist crossed the line, race announcer Jeff Roak said "they are dancing in the streets here in Atlantic City."

But according to the Chicago Tribune, no was dancing.

Still, Trump was enthused about both his name's use and the race's future prospects.

He wanted the race to be longer next time.

"It can start in New York and go out to San Francisco, throughout the country," he said. "I really feel that when I attach my name to something, I have to make that something successful. My name is probably my greatest asset and I have some nice assets."

Yet he pulled out in 1990, after just one more race.

Despite the success that the races had, Trump reeled back because of the Trump Organization's financial issues at the time.

The race continued without Trump.

It was renamed Tour DuPont, after the DuPont family, who took over sponsorship.

Cyclist Lance Armstrong went on to win it twice. Then, in 1996, it was canceled when DuPont Corporation pulled sponsoring.

Experts say the race, overall, was a plus for the cycling community.

In 2016, USA Cycling President Kevin Bouchard-Hall told Politico that races had been great for cycling, despite its odd origins.

"They were wildly successful endeavors which raised the profile of American cycling internationally and, within the US, raised the profile of the sport of cycling," he said.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement