- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- The rise and fall of the 'Greatest Show on Earth' and the Ringling family's circus empire

The rise and fall of the 'Greatest Show on Earth' and the Ringling family's circus empire

The Ringling brothers' parents moved to Baraboo, Wisconsin, in 1855. The small town would later become the circus headquarters.

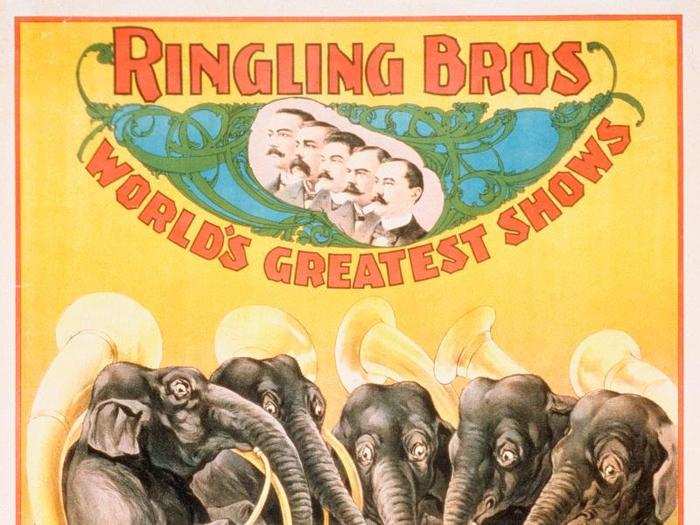

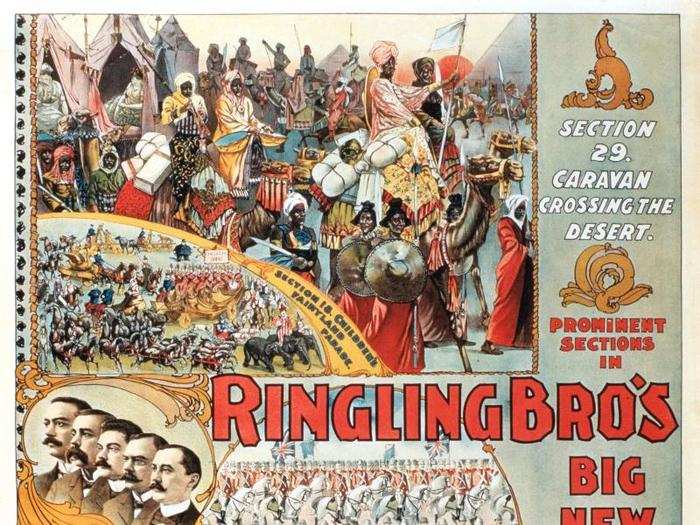

Of the Ringlings' seven sons, five joined together to begin the infamous Ringling Bros. Circus.

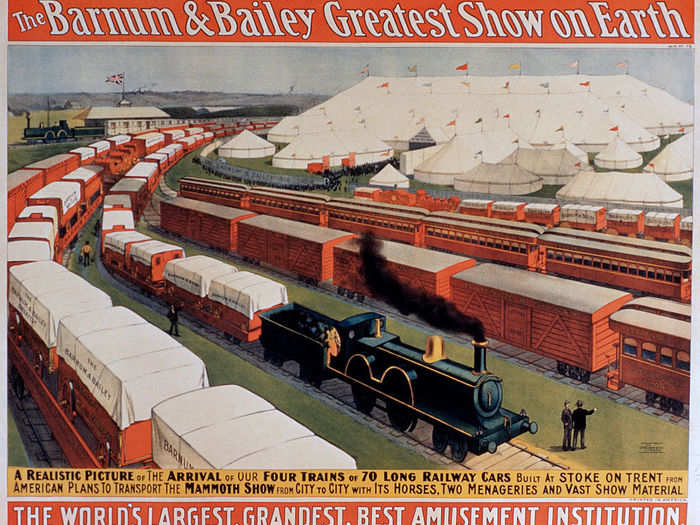

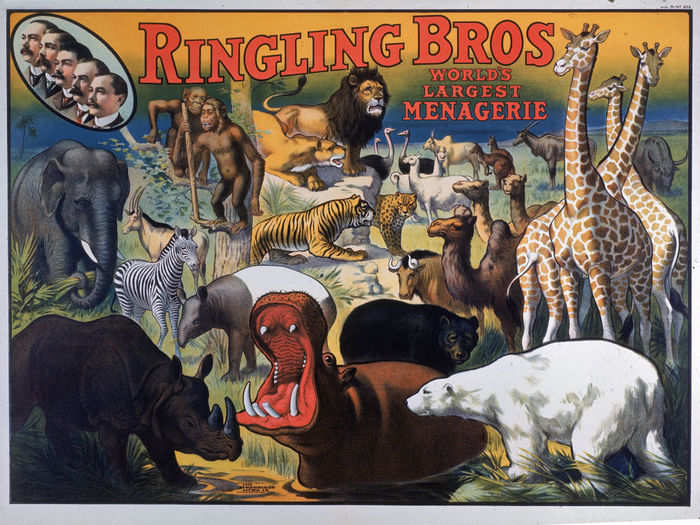

Though they started with one- and five-cent shows, the Ringling brothers would later own a "flock of circuses" eventually combined to form the "Greatest Show on Earth" — a name adopted in 1919 after the Ringling Bros. Circus merger with the Barnum & Bailey Circus. The second-youngest brother John Ringling was instrumental in the deal, purchasing the circus from James A. Bailey's widow in 1907 (cofounder PT Barnum, who started Barnum's American Museum, had died 10 years prior).

After witnessing show animals arrive by boat one early morning in 1870, the Ringling brothers decided to form their own circus. "Alf T. Ringling states that as he and his brothers walked home for breakfast, they talked together for the first time of having a circus of their own," wrote Henry Ringling North in his memoir "Circus Kings: Our Ringling Family Story."

Alf T. Ringling wrote in 1900 that "When the last wagon had rolled slowly up the bank, Al, with a sigh of relaxation, turn to Otto and said: 'What would you say if we had a show like that?' "

The very first show charged an admission price of one cent for the children of McGregor, though the show ended up netting $8.37. The following year, the brothers put on their first "real show," which they consider to be the first official Ringling Brothers circus performance, charging five cents per ticket.

After spending a few years supporting both the family business and their own individual pursuits, the Ringling brothers joined together in 1882 to put on a show called "Ringling Bros. Classic and Comic Concert Co." The production earned just $13, while the costs to run the show totaled $25.90.

The show, which would later turn a huge profit, went by many names after that performance, including "Ringling Bros. Grand Carnival of Fun," "Ringling Bros. Great Double Shows Circus, Caravan, Trained Animal Exposition," and "Ringling Bros. World's Greatest Railroad Shows, Real Roman Hippodrome, 3 Ring Circus and Elevated Stages, Millionaire Menagerie, Museum and Aquarium and Spectacular Tournament Production of Caesar's Triumphal Entry into Rome."

These ventures eventually grew to what was known as 'The Greatest Show on Earth' — and included a considerable fortune

In his memoir, the Ringling brothers' nephew Henry Ringling North wrote, "My uncles, the seven Ringling brothers, had also gone a long way from poverty-stricken country boys who had dreamed of owning a great circus and made their dream come true doubled in spades."

While not all of his uncles lived long enough to enjoy the massive fortune, several — especially John and Charles — were able to spend their riches on large homes, yachts, and luxury vehicles.

During its heyday in the Roaring '20s, Ringling Bros. Circus netted millions of dollars and was considered one of the most impressive live shows. The circus was made especially profitable after the brothers began using railroads to travel to both small towns and big cities by train.

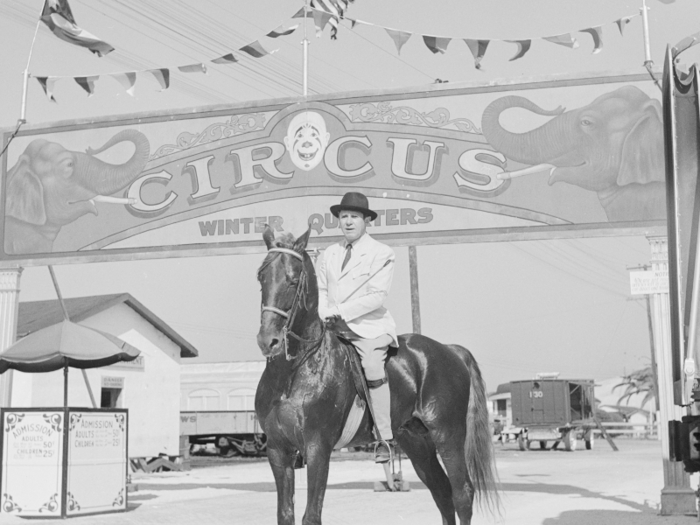

For a significant chunk of of its 150-year collective lifetime, the show was headquartered in Baraboo, Wisconsin, which became known as 'Circus City.'

According to Henry Ringling North's description, the small town housed both performers and animals during the winter months. Known as "Winter Quarters," the area included stables, bunks, and wagon and blacksmith shops. According to the Ringling nephew's account, the usually-quiet Midwestern city was home to up to fifty elephants and other wild animals during its coldest season.

Along with the buildings for their circus crew, the brothers also owned a hotel and other properties. Since the 1950s, the remnants of Winter Quarters make up Circus World Museum. As a result of these historic buildings, along with several of the family's original houses, Baraboo is one of the locations most associated with the seven Ringling brothers.

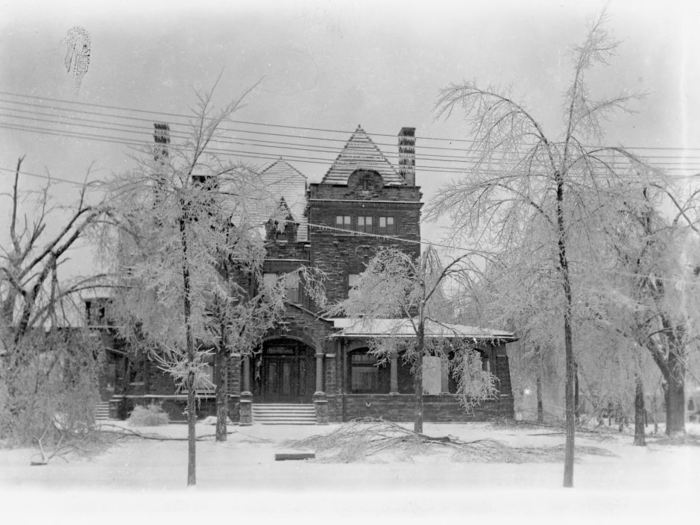

Al Ringling especially loved Baraboo, and was the only brother who maintained a permanent residence in the small Wisconsin town.

While the brothers always returned home for holidays and other family business, Albert Ringling (otherwise known as "Al" or "Uncle Al") was especially fond of Baraboo and made it his permanent home.

After Al Ringling died in 1916, his sister and his nephews moved into his mansion. One of his nephews, Henry Ringling North, describes living in his uncle's "great, turreted, Renaissance-style mansion, half castle and half chateau, built of Lake Superior sandstone." In his memoir "Circus Kings," Ringling North details the chateau: a dark-paneled library, a massive ballroom, a wine cellar, stables, and ceilings covered in gold leaf.

According to Ringling North's memoir, his "Uncle Al" served as equestrian director of Ringling show and was known by his nickname to the public as well as his family. In addition to his role as an equestrian director, he was also skilled at tightrope walking and always practiced "juggling and aerobatics." His greatest achievement as equestrian director was a show that included 61 horses in 1899.

In addition to his estate, Al Ringling built a theater for his hometown.

Two years before he died, Al built a $10,000 theater for the city of Baraboo. The Al Ringling Theatre still stands today and is marked as a historical spot. According to his nephew's memoir, the building — recently restored in 2016 — was built as "an almost perfect copy" of Marie Antoinette's theater at Versailles.

The family's second oldest and youngest siblings, August Ringling and Henry Ringling respectively, were the last to join the original five founders in the family business.

According to "Circus Kings," the Ringling brothers made Augustus "Gus" Ringling the advertising manager of the circus in 1891. One of the last to join the family business, Gus previously worked as a carriage trimmer. Gus died in 1907 and by this time "the others were living in considerable splendor, each according to his taste," according to Henry Ringling North's memoir. The second-eldest Ringling brother had three daughters: Mattie, Lorene, and Alice.

Meanwhile the second-youngest sibling, Henry Ringling, originally began helping his brothers by working the door at the circus shows. His nephew Henry Ringling North wrote, "Until 1931, Ringling Brothers was not a corporation, but a simple partnership. As one by one the partner-brothers died, the survivors made a settlement with heirs and carried on." Henry took over some of his brother Otto Ringling's responsibilities when he died, and had one son named Henry who never joined the circus industry.

Otto Ringling was known as 'The King' for his financial power when he was alive.

According to his nephew's memoir, Otto Ringling became known as "The King" for his power with financial matters. According to the account, he gave the final approval for John Ringling's idea to purchase the Barnum & Bailey Circus for $410,000. After the purchase, the Ringlings commanded their own train and the Barnum & Bailey train until they finally merged the two shows in 1919, after Otto's death. While he was alive, Otto used his fortune to build a library of "fine books."

In his New York Times obituary, his brothers additionally labeled "The King" as both "the financier of the family" as well "the Lieutenant General." In his will, which he had presented to his brother John, he distributed his hundreds of thousands of dollars to his nieces and nephews (much of it in trusts). John later took over much of Otto's financial duties, while his brothers maintained their separate responsibilities.

Alfred Ringling served as the head of public relations, and settled in what is now Oak Ridge, New Jersey.

Henry Ringling North wrote that Alfred Ringling — otherwise known as "Alf T." — headed public relations and was pivotal when the growing performance company competed with other area shows in the late 1890s. Like their father before them, Alfred and his brother Charles worked in the harness making industry before the circus became a national success.

While his brother Al invested in the brothers' hometown of Baraboo, Alf T. invested in the Petersburg area of New Jersey, which is now known as Oak Ridge.

"Ringling purchased 600 acres and began to build his estate in 1913," reported the New Jersey Herald. "Along with the 28-room mansion, Ringling constructed outbuildings to house his menagerie of horses, elephants, birds and other animals. Two massive dams were erected to change Petersburg Pond into what is now Lake Swannanoa."

The 28-room home was completed in 1916 and now sits on just 4.2 acres of land. The home was listed for $800,000 last year. Completed in 1916, it is estimated to have cost $300,000, equivalent to $6.9 million today. Alf T. died in the manor in 1919 — just three years after its completion.

The property was also briefly used as the winter quarters for his son Richard's circus, the R.T. Richards Circus. Richard ended his involvement with the circus after barely two years, and moved to Montana to work as a rancher. According to historian Fred Dahlinger Jr.'s 2008 afterword in Henry Ringling North's memoir, Richard's son Paul continued operating the ranch in Montana. However, both Ringling men maintained connections with the family business while they were alive. Paul Ringling died in 2018. The land, purchased by John Ringling, is still known as Ringling, Montana, today.

Alf T.'s granddaughter, Mabel Ringling, worked in the equestrian industry.

After the death of their brothers, Charles and John Ringling remained the two key players in the family business. Charles settled in Sarasota, Florida, as did John.

Known as "Mr. Charles," Charles Ringling commanded the circus train and took on duties similar to that of a general manager, keeping a "Book of Wonders" to record the circus going-ons during his time traveling the rails.

In his memoir, Henry Ringling North wrote, "Uncle Charles had a splendid car called the Caledonia, furnished in magnificent red plus and gold, with real lace curtains." He also noted that his uncle — who maintained a love of music — collected rare violins.

In addition to his massive homes in Wisconsin and Florida, Charles purchased the Gillespie golf course and developed the business sector of Sarasota, along with constructing the Sarasota Terrace Hotel. Nearby, Ringling Boulevard is named after him, as well as other buildings.

Charles' wife Edith would later play a major role as she fought for management control after Charles' death.

After her husband's death, Edith and her children each received a third of Charles' shares. In 1943, Edith used this majority to nominate her son to the role of president and director, which had been given by default to his cousin, John Ringling North II.

Edith and Aubrey Ringling — Edith and Charles' niece by marriage — collectively held 63% of Ringling shares in the early 1940s. They used this controlling power to nominate Robert Ringling as vice president of the circus.

The couple had two children — Robert and Hester. Robert briefly served as president of the Ringling circus organization for three years.

Robert briefly served as president of the Ringling Bros. Circus from 1943 to 1947, during which the Hartford Circus Fire tragedy occurred. Robert's brief internment caused a bit of family tension: The new president was advertised as the return of a Ringling heir, as Robert was the only one of the original founding brothers' sons to assume the role.

"A Ringling son has taken his rightful place in the circus sun," the circus program read, according to Henry Ringling North's memoir. "The mantle of the Ringling Brothers, the famous founders of the Ringling Circus, has been draped on the broad shoulders of Robert Ringling, son of the late Charles Ringling, one of the most brilliant showmen that ever lived."

Robert's sister Hester continued to live on the massive property her father built in Sarasota, Florida in one of the estate's houses with her husband and children. Her home is now known as South Hall, a part of the New College of Florida's campus.

Charles Ringling's estate, which Edith, Hester, and Robert occupied until their deaths, is now known as South Hall.

The estate was, and still is, known for its pink marble and expansive rooms. A walkway now connects the main house to the additional homes, where Hester and her family lived until her death.

The home is considered Charles Ringling's best displays of wealth and cost $10 million to build in the 1920s, according to his nephew's memoir. Additional luxuries of Charles included a fleet of 120 carriages, a yacht called Symphonia, and many acres of Florida property.

Charles' brother John built the neighboring Ca' d'Zan mansion. The house name is Venetian for 'House of John.'

Always wanting to leave his hometown of Baraboo, John first lived in a hotel in Chicago. His nephew said, "The only one who did not live part of the time in Baraboo was Uncle John, who became the most famous of them all."

At the time of its completion, the massive 56-room Venetian style palazzo included many amenities described by Henry Ringling North: a barroom with glass panels from St. Louis' famous Cicardi Winter Palace Restaurant, a master "ballroom-sized bedroom,"and a bathtub cut from Siena marble. In his memoir, Ringling North also noted that John Ringling was able to keep an impressive supply of expensive alcohol during the prohibition years.

"With its furnishing, not including the tapestries and works of art, Ca' d'Zan cost Uncle John $1,650,000," reported Ringling North.

A New York Times feature by Geraldine Fabrikan described the extraordinary work that went into restoring the palace and the works of art during the early 2000s, spearheaded by curator Ron McCarty. Relics were collected from family members and donors, including "a black crepe beaded gown with sequins from French & Company that cost $1,800 in 1923" once belonging to Mabel Ringling. The Times reported that in addition to tracking down items, many of the closets and bureaus in the mansion had remained locked — and full of valuable objects — for years as the estate fell into disrepair.

"We got a locksmith to open the bureau, and we found all John Ringling's Charvet ties lying in rows," curator Ron McCarty told The Times.

The home and art exhibits — which were gifted to the state of Florida at the time of John Ringling's death — are now open to the public. John, his wife Mabel, and his sister Ida are all buried in the estate garden.

Ca' d'Zan also included a separate art museum to house John's ever-growing collection.

When John Ringling began visiting Europe to scout for new talent for his shows, he also began collecting paintings. His nephew noted that one of his favorite pastimes was looking for new additions at Christie's in London.

"But the fact remains that his do-it-yourself art education enabled him to amass a collection of old masters — he never bought modern pictures — which at the time of his death was appraised at close to $15,000,000, about five times what he paid for it," wrote Henry Ringling North. "His collection put the John and Mable Ringling Museum in the first rank among the galleries in the world."

Collection pieces noted by his nephew's memoir included a Tintoretto painting — purchased for $200 but appraised at $50,000 — and a Rubens painting of the Duke of Westminster for $150,000. A similar painting later sold at an auction for over five times that amount. Many of these paintings remained in storage for years. Part of Ron McCarty's mansion project included restoring these paintings, along with the elaborate ceiling murals, for display.

Arguably the most famous Ringling Brother — and credited with the merger of Barnum & Bailey — John Ringling had many business ventures and spent much of his life mingling with wealthy investors.

Despite being hailed as an impressive businessman, John Ringling never finished high school. John started out with creating routes for the circus train, later working to bring in new acts for the show, often from Europe. His most famous business move, perhaps, is buying Barnum & Bailey for $410,000. John was later instrumental in moving the combined show from Bridgeport to Sarasota, where he purchased property for a new headquarters.

In his book "Circus Kings," John Ringling's grandson wrote about the famous business move: "Having achieved one ambition by masterminding Ringling Brothers' purchase of Barnum & Bailey, he was just starting to build the great financial empire which made him, for a time, one of the richest men in the world."

During these years, John Ringling also remained involved in his real estate company, the oil industry, and the purchase of railways.

His most notable ventures, however, stayed with the circus. In addition to his life-changing purchase of Barnum & Bailey, John Ringling bought the American Circus Corporation outright for $1.7 million.

Though John amassed a considerable fortune, he died with just $311 in the bank.

After Otto died, John became the new family financier, and after Charles died, John remained the only living Ringling brother for over a decade.

Like his other brothers who lived long enough to enjoy the family wealth, he later indulged in other luxuries besides his paintings. According to his nephew's accounts, John had an affinity for luxury vehicles: "He never owned anything but Rolls-Royces and Pierce-Arrows."

Additionally, John Ringling purchased custom-made suits from Saville Row and Mr. Bell of New York. Prior to Ca' d'Zan, Ringling also lived on Dearborn Avenue in Chicago and Fifth Avenue in New York, along with purchasing a manor in Alpine, New Jersey.

Despite many years of luxury, John Ringling experienced financial troubles during the last years of his life due to the burden of the Great Depression. (His nephews, however, would later rebuild some of the family's wealth.)

An entry in his nephew's memoir reads: "On December 2, 1936, John Ringling died. He had $311 in the bank. His estate was officially appraised at $23,500,000."

Of the eight Ringling children, the youngest sibling was Ida, born in Baraboo but significantly younger than her oldest brother.

According to her son's memoir, Ida Ringling married Henry Whitestone North, a railroad engineer. She spent time living in her brother Al's Baraboo chateau after his death, and later moved into the Bird Key island's "New Edzell Castle" where she lived until her death in 1950. Also known as the Worcester Home, Ida's brother John originally intended for the property to be used as President Warren G. Harding's "winter White House."

Ida Ringling North had three children: John, Henry, and Salóme.

Her two sons, John and Henry, would succeed her brothers as circus kings.

The two brothers are largely credited with modernizing the circus, and — more importantly — bringing it back to firm financial standing after the Great Depression. One of their earliest purchases, which revitalized the show's acts, was "Gargantua the Gorilla," for which they paid $10,000.

The brothers also made two pivotal decisions later in their career: ending big-top tent performances in favor of arena shows and ultimately selling the circus to the Feld family in 1967.

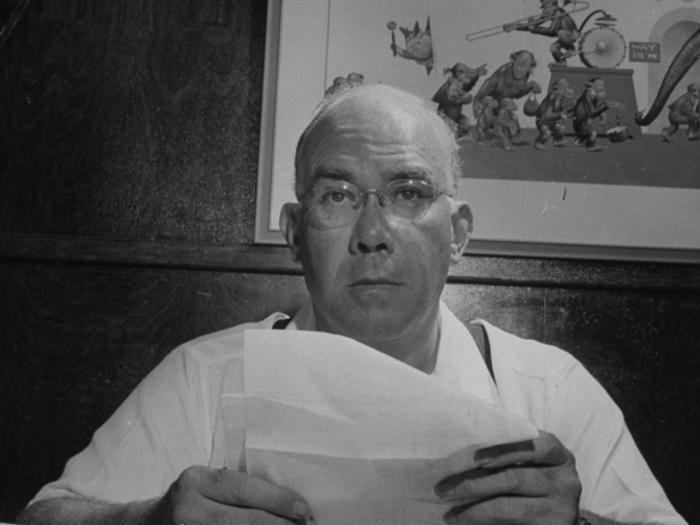

John Ringling North served as president and director for the majority of his life, following his uncle's lead.

Described by his brother as inheriting the "Ringling touch," John Ringling North, like his uncle and namesake before him, began working to bring new acts to the show following the Great Depression. He brought notable people, including the Great Wallendas.

Originally working for his uncle's real estate business, Ringling later handled the circus' banking matters while also working on Wall Street.

After John and Henry helped restore much of the family's wealth, Henry reported that his brother spent $20,000 on his honeymoon.

"John Ringling North passed away in 1985, having achieved a wealth far beyond his more famous uncle," reported circus historian Fred Dahlinger, Jr. in the afterword of Henry Ringling North's memoir.

Henry Ringling North served as vice president and remained involved in the circus' railroad travel until its end in 1956.

After years working for his uncles' circus, Henry Whitestone Ringling North penned "Circus Kings: Our Ringling Family Story," which follows the circus family's history up to 1960. The published afterword provides the reader with additional information into the early 2000s, still before the Ringling Brothers ceased for good.

Henry Ringling North spent years working for his uncle John, describing much of this time period in his memoir.

"Life was very strange during the years I spent at the Ca' d'Zan with Uncle John, serving him as business agent, chauffeur, handyman, and sometimes cook," Ringling North wrote.

After the sale of the circus, Henry Ringling North, along with John Ringling North, spent time in Europe. Henry purchased their father's ancestral Galway home, and the two became Irish citizens. Henry also lived in Belgium and Switzerland, dying in Geneva in 1993.

Ringling North had one child, a son named John Ringling II after his uncle and great uncle. Ringling II was involved in the circus industry, owning the Kelly Miller Circus from 2006 to 2017.

After growing up with the circus, John Ringling II decided to take after his namesake uncle and great uncle before him, purchasing the Keller-Miller circus in 2006. According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Ringling North II has three children: two daughters named Katherine and Sorcha and a son named John Ringling North III.

"I knew I couldn't equal what my father, my uncle, their uncles did, but I wanted there to be a circus even in a one-ring format, the kind of circus I remember from those days," Ringling North II said in a 2012 interview. "And I said if I don't come, who's going to do it?"

Ringling North II operated the Oklahoma-based circus for just over a decade, until animals were banned from most traveling shows. This coincided with the last Ringling Bros. show, held in May of the same year.

Ringling II's involvement with the show is the family's most recent — and perhaps last — involvement in the circus industry. The Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus officially closed in 2017.

Prior to the Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey Circus close in 2017, the most famous date was in 1956, marking the last big-top tent performance. Following the final show in Pittsburgh, the brothers turned the production into a arena-only operation. The circus most notably performed as a resident show at Madison Square Garden in New York City, continuing a tradition started by Henry and John's uncles years before.

After over 80 years operating the circus, the Ringling family sold the show to the Feld family who had been involved in the business for some time. The deal was signed at the Colosseum in Rome. According to historian Fred Dahlinger, Jr., "North and the minority owners, all veterans of battles for control, split the $8,000,000 paid for the family legacy."

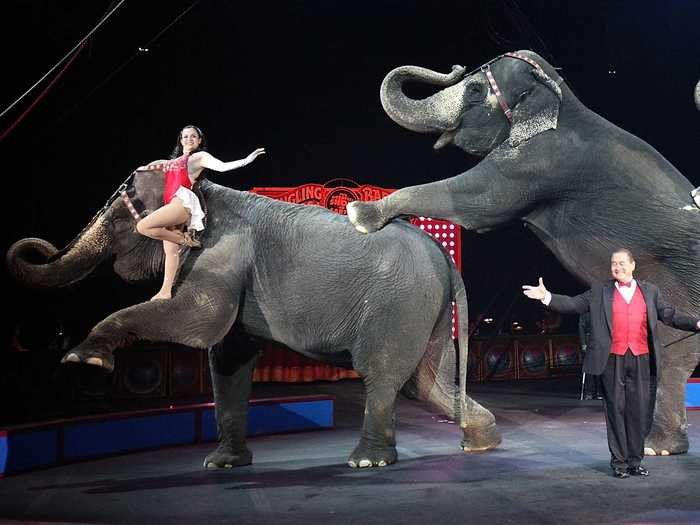

The Felds continued the show for another 50 years, first announcing in 2015 that the circus would eliminate elephant acts by 2018. This decision was quickly amended, and the 13 Ringling elephants retired a year and a half early in 2016. A few months later, the Feld family announced the circus would not continue at all.

The Felds announced that there was no "one reason" for the circus' closure — but declining sales and mounting pressures from animal rights activists were two contributing factors. The final show was held on May 21, 2017, at the Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum on Long Island.

The closing message for the collective 146-year operation, stated by the show's ringleader, announced, "We never say goodbye in the circus, my friends. All we say is, we'll see you down the road."

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement