- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

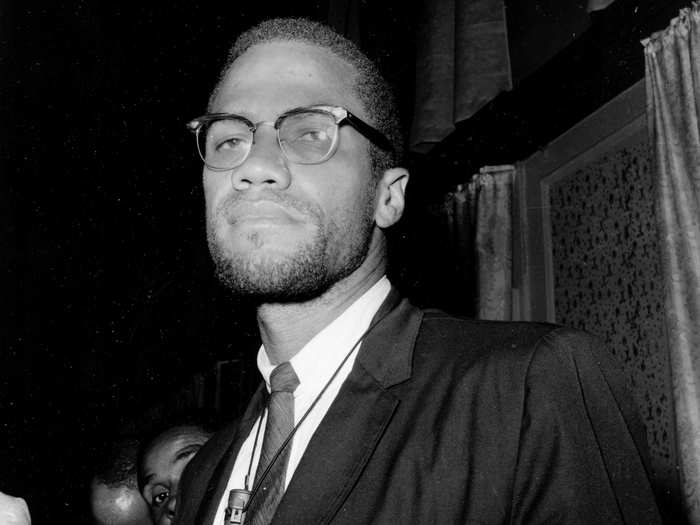

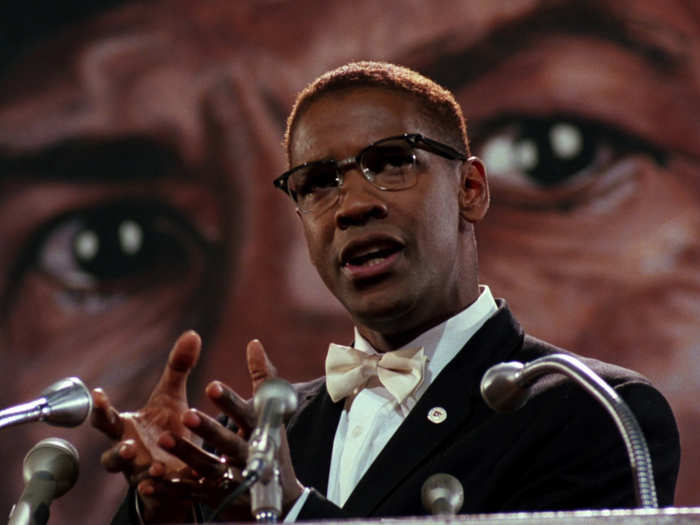

- The life and assassination of Malcolm X, the controversial civil rights activist whose death remains a mystery

The life and assassination of Malcolm X, the controversial civil rights activist whose death remains a mystery

Malcolm Little was born on May 19, 1925 in Omaha, Nebraska. He was the fourth of seven children. His father, Earl, was a Baptist preacher. He and his wife Louise were activists. They were also a poor family.

Earl was an outspoken follower of black nationalist Marcus Garvey, and moved the family around to keep them safe, finally settling in Lansing, Michigan. But even then, their home was burned down, most likely by a white supremacist group. No fire truck showed up.

Two years later, when Mal com was six, Earl was later found dead on railway tracks. Police called it an accident, but his mother thought white supremacists were responsible.

Sources: The New Yorker, History.com, PBS, History Cooperative, Al Jazeera

In 1938, Malcolm's mother Louise had a mental breakdown and was sent to a mental institution. Malcolm X and his siblings were dispersed into foster homes. After dropping out of school in seventh grade, Malcolm X returned eighth grade.

Source: PBS

He was class president and got top marks. But his white teacher told him he would never reach his dream of becoming a lawyer because he was black. His teacher's comment showed him how white people could be hostile to African Americans.

Source: History Cooperative

As a young man, at about 14, he started working odd jobs, before ending up in Harlem, New York in 1943. There, he dressed in zoot suits, sold drugs, and worked as a pimp. His reddish hair earned him nicknames, like "New York Red."

Later biographies have asserted he exaggerated his criminal youth to create a stronger personal story.

Sources: The New Yorker, The Guardian, History.com, History Cooperative

In 1943, he avoided fighting in World War II. He responded to his draft notice by saying he would fight for the Japanese, and kill white Americans. He was classed as mentally unfit.

Source: PBS

In 1946, at 20, he returned to Boston. He was promptly sent to prison for larceny, after going on a burglary spree with several friends. He was caught trying to repair a stolen watch worth $1,000.

Sources: The New Yorker, History.com, PBS, History Cooperative

As he served an eight-to-10-year sentence, he educated himself. According to his biographer Manning Marable, along with black history, he read western philosophers like Herodotus, Kant, and Nietzsche.

Sources: The New York Times, The New Yorker, PBS

While he was in prison, his siblings introduced him to the Nation of Islam. After studying the religion's program, he sent a letter to its leader Elijah Muhammad, declaring his loyalty. He had written the letter 25 times before getting it right.

In response, Muhammad sent back a single five-dollar note.

Sources: The New York Times, The New Yorker

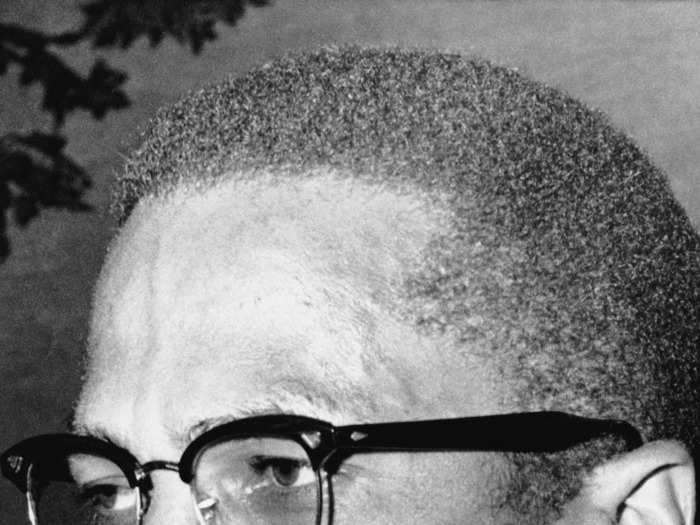

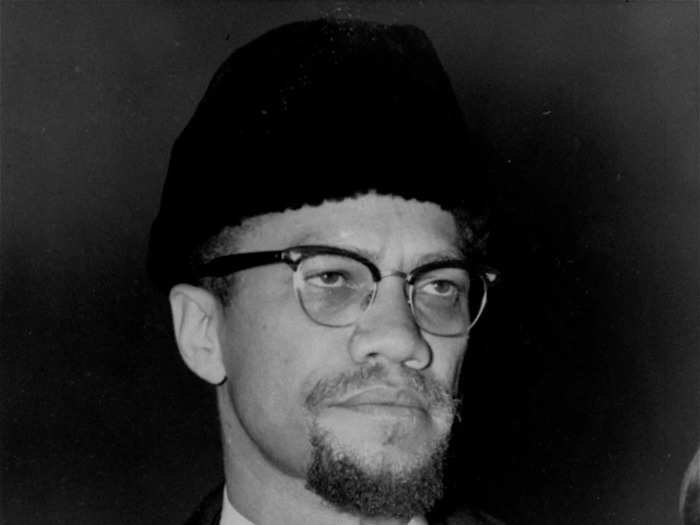

In 1952, he was released from prison. He was 27. He dropped his surname "Little" because, he said, slaver owners had given the name to his family. He called himself Malcolm X. The X was a symbol of his unknown African name. He also quit drinking and smoking.

Sources: PBS, History Cooperative, Al Jazeera

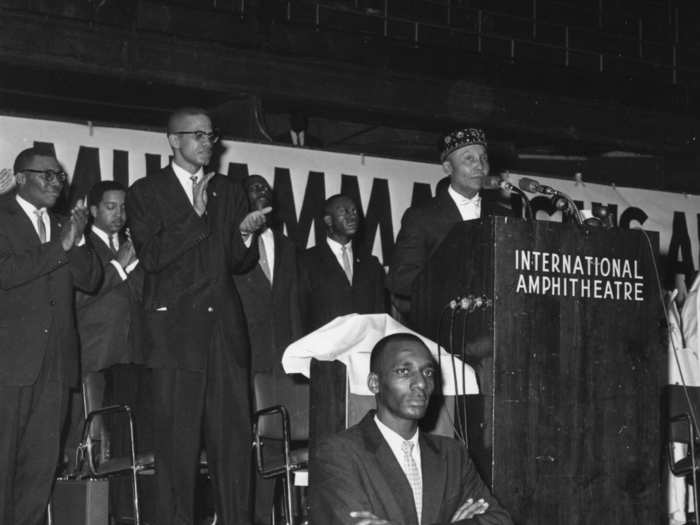

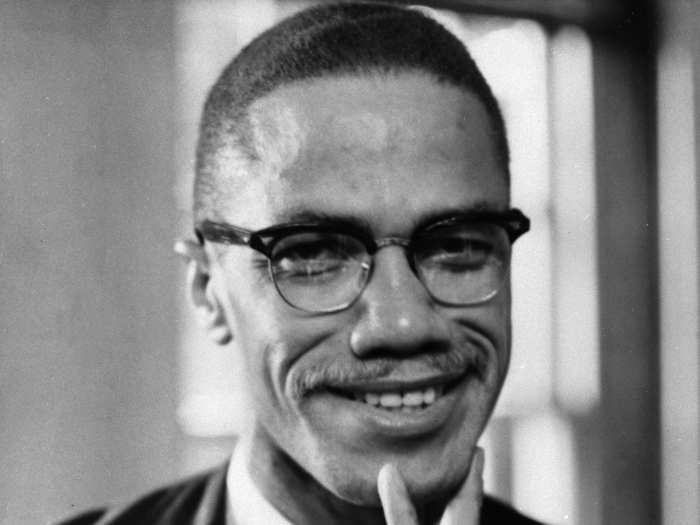

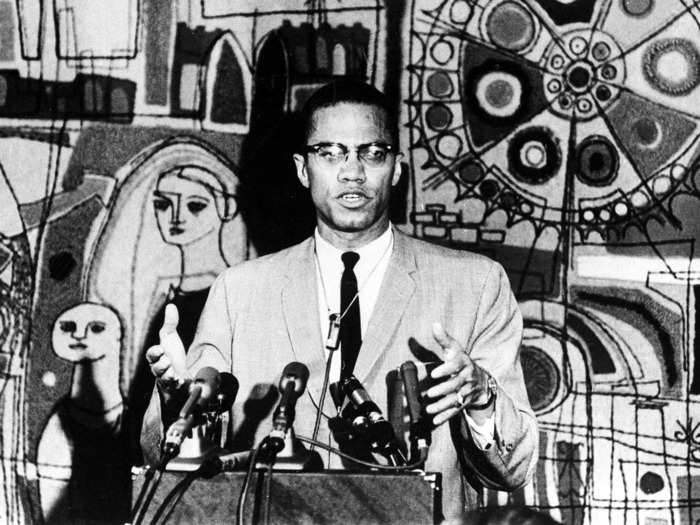

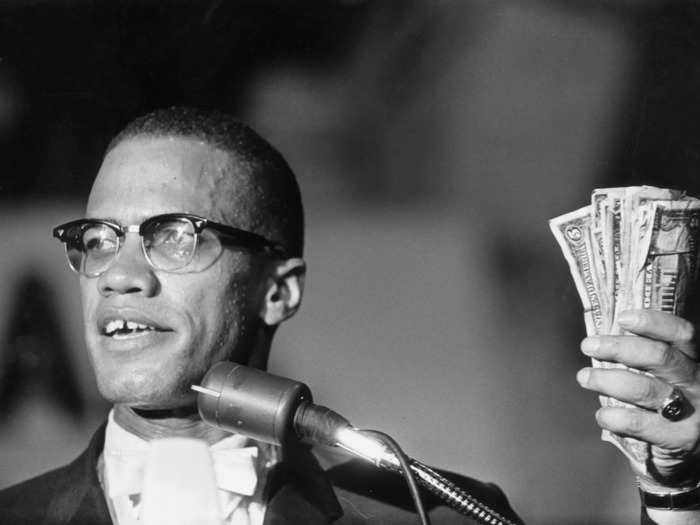

At that point, membership to the Nation of Islam numbered in the hundreds. Elijah Muhammad saw Malcolm X's public-speaking talent and charisma — traits he lacked — and dispatched him to spread the group's teachings and open temples in Detroit, Boston, and New York.

Sources: The New Yorker

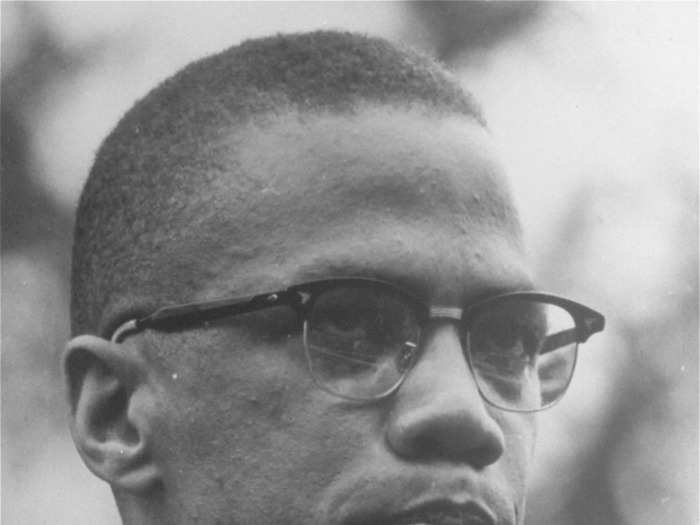

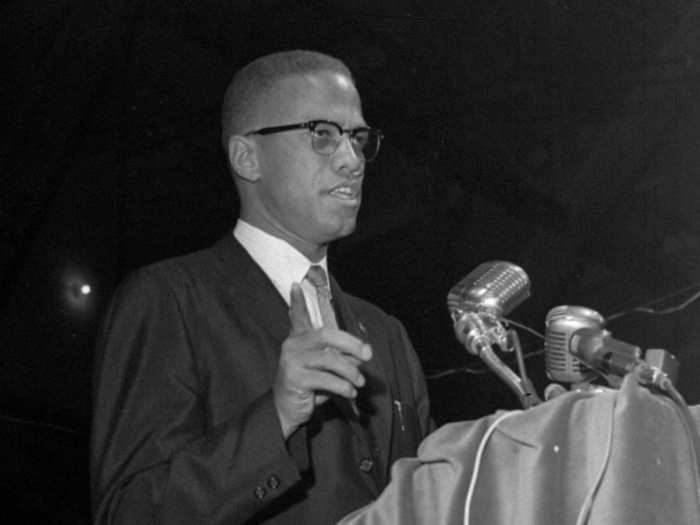

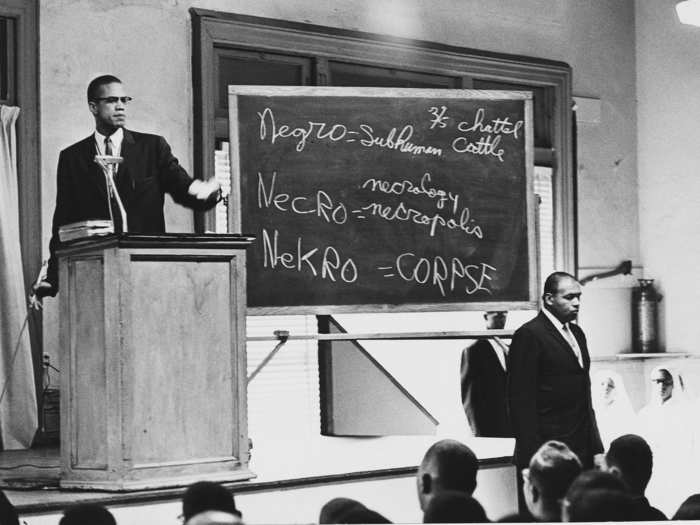

Malcolm X quickly became the movement's most successful minister. He touted violence as a necessary tool in self-defense, and called white people, the "blue-eyed white devils."

Sources: The New York Times, History.com, Stanford

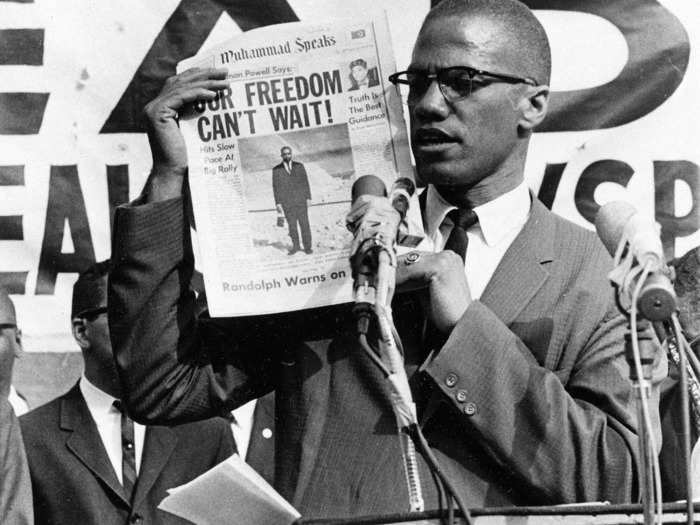

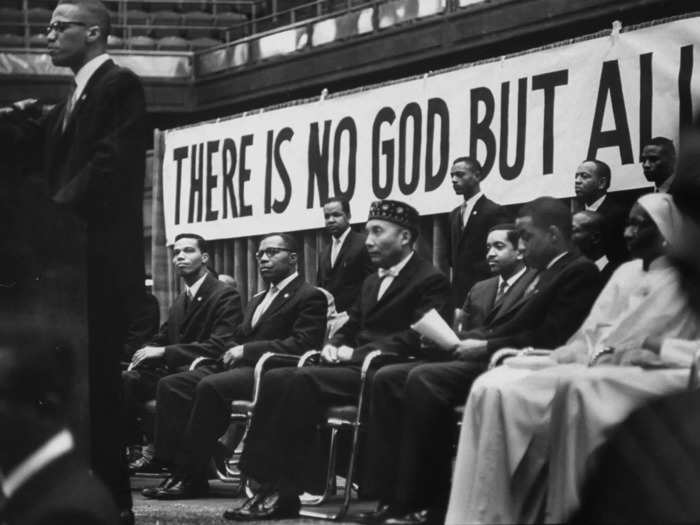

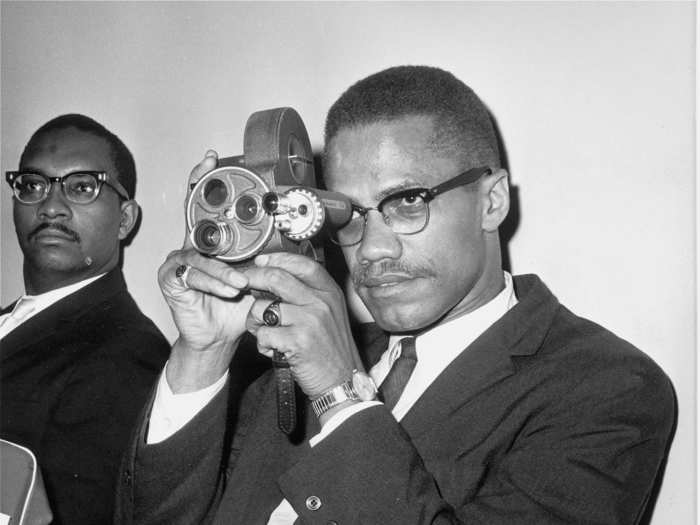

He started a newspaper called "Muhammad Speaks," and called for radical change such as black separatism, whereby black people would remove themselves from predominantly white institutions and even nations.

Sources: CNN, Al Jazeera

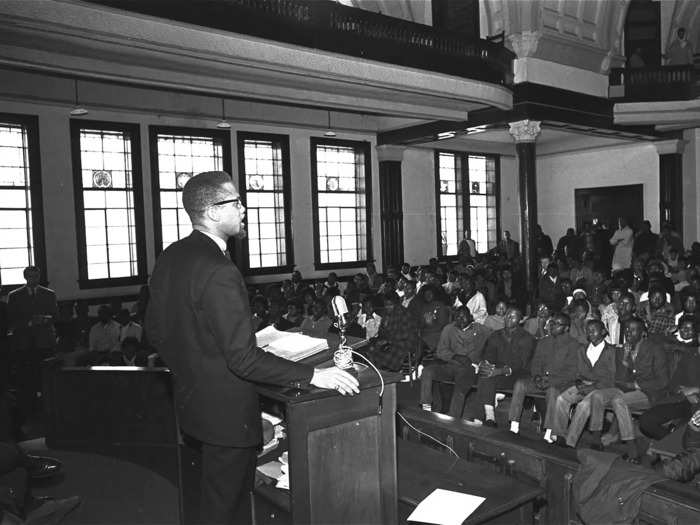

Instead of integration, he wanted self-determination "by any means necessary." His speeches began to garner national attention in the late 1950s. By 1954, the FBI was monitoring him.

Sources: CNN, Al Jazeera

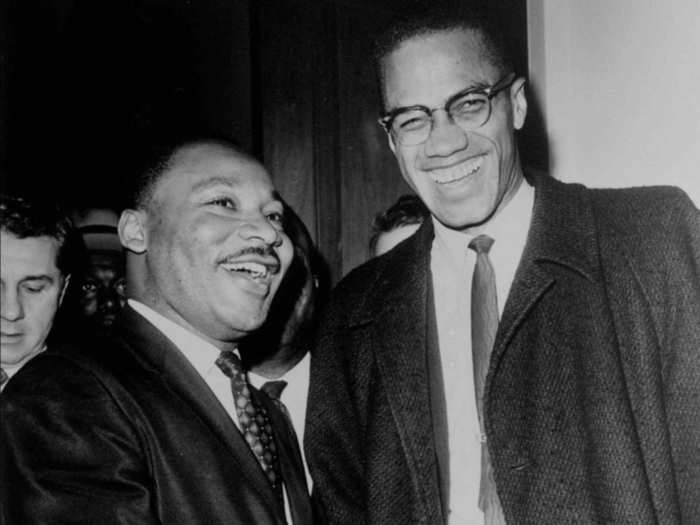

His rallies were in direct contrast to civil rights activist Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s calls for peaceful, multiracial protests. The pair had a tumultuous relationship. Malcolm was more aggressive, and had called King "an ignorant Negro preacher."

Sources: The New York Times, Complex, The New York Times

In 1953, after King made his famous "I Have a Dream," speech, Malcolm X responded to the civil rights leader, saying, "Who ever heard of angry revolutionists all harmonizing 'We Shall Overcome' … while tripping and swaying along arm-in-arm with the very people they were supposed to be angrily revolting against?"

Source: History.com

In 1954, Malcolm X became the chief minister of Mosque No.7 in Harlem. He had previously served as an assistant minister in Detroit, and first minister in Boston.

Sources: History.com, PBS, Stanford

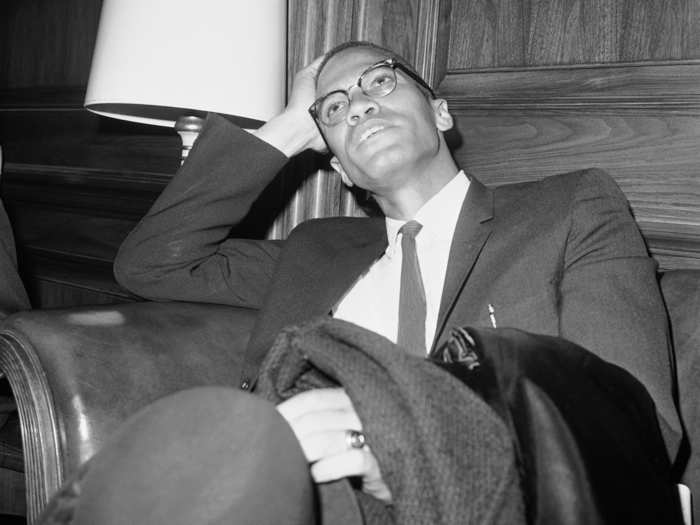

In 1957, he became the Nation of Islam's national representative, which made him the number two man to its supreme leader known as Elijah Muhammad.

Sources: History.com, PBS, Stanford

That same year, a temple member named Johnson Hinton was beaten by New York police, after he tried to stop them from hurting another man outside the temple. Hinton was then taken into police custody, without medical care.

Sources: Complex, History Cooperative

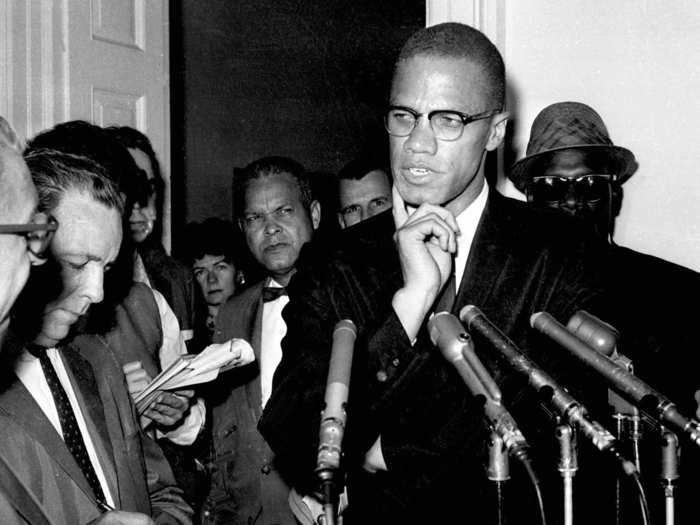

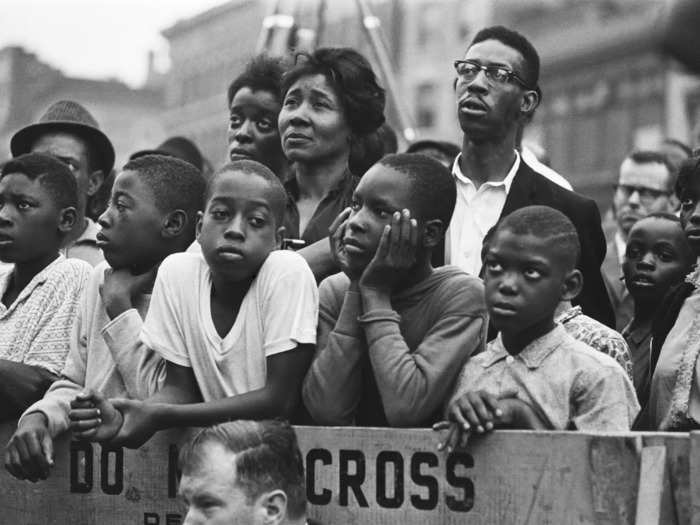

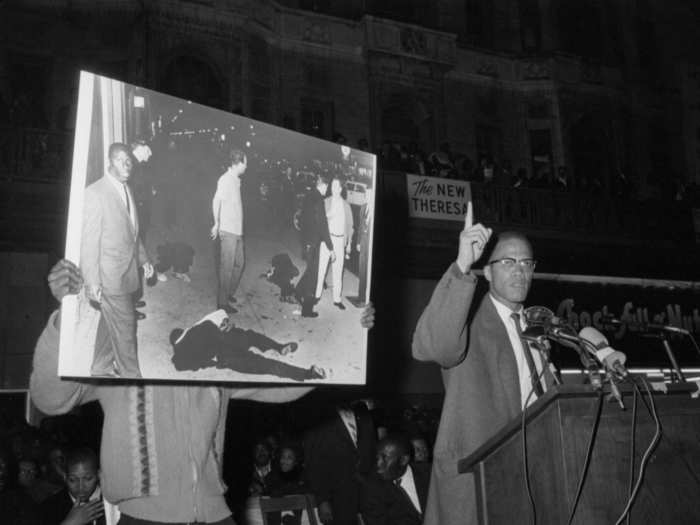

Malcolm X and several hundred protesters marched on the police precinct, demanding Hinton get medical attention. When the police relented, he dispersed the protesters with a wave of his hand.

His victory against the police was covered nationally by the media.

Sources: Complex, History Cooperative

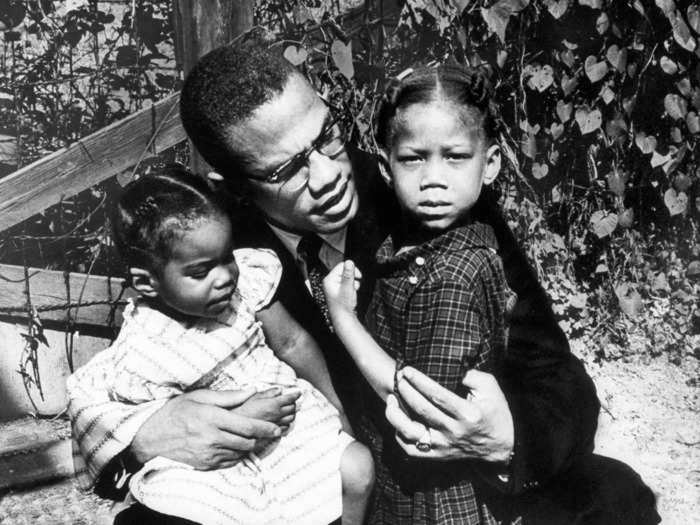

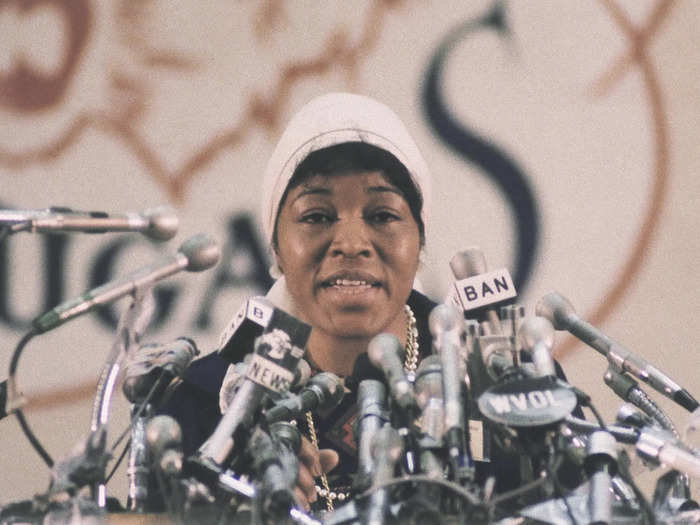

In 1958, he married Betty Sanders, who became Betty X, and then Betty Shabazz. Within a year, the marriage struggled; and Malcolm X in a letter sent to Elijah Muhammad, revealed the main problem was sex. Allies of Muhammad who didn't like Malcolm publicized the information to hurt him.

Sources: The New Yorker

In 1959, a documentary called "The Hate That Hate Produced," thrusted the group into the national consciousness. According to The New York Times, it was after the documentary when "white America learned to be nervous about the Nation of Islam."

By 1961, the group had up to 75,000 members.

Sources: Complex, The New Yorker, The New York Times

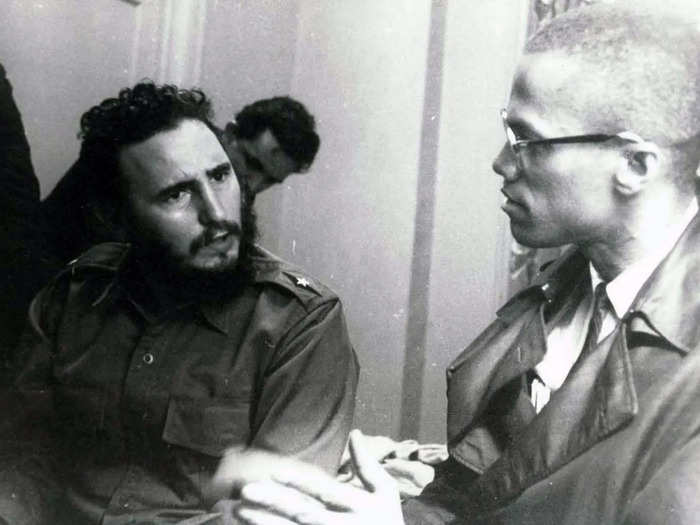

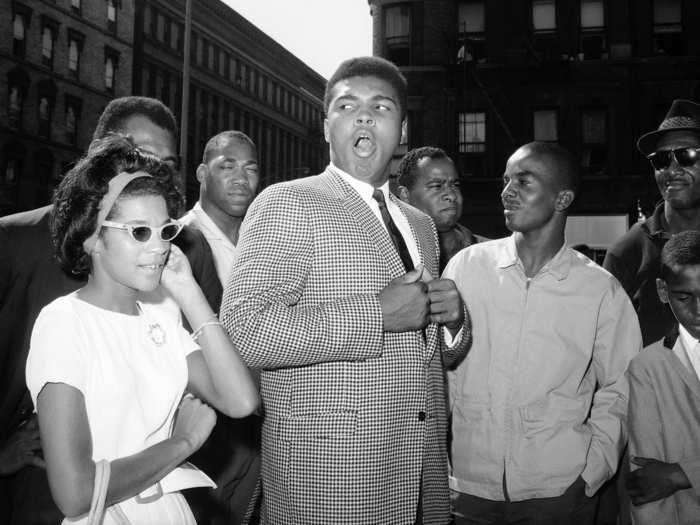

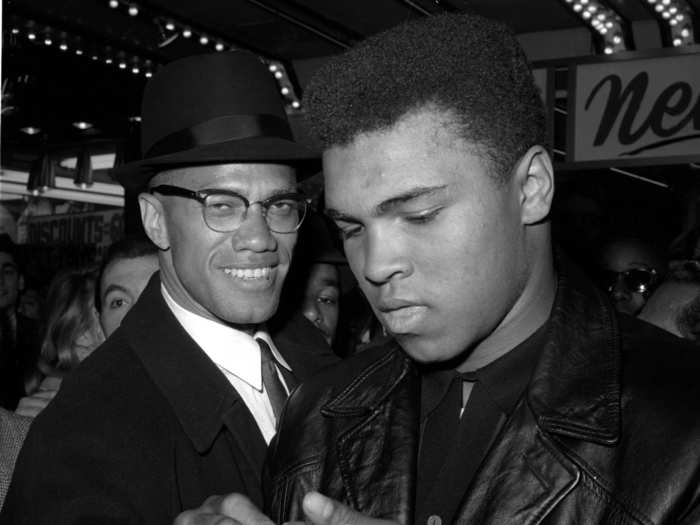

Malcolm X's success brought him into the orbit of famous people, like Cassius Clay. Their friendship led to Clay joining the Nation of Islam and renaming himself Muhammad Ali.

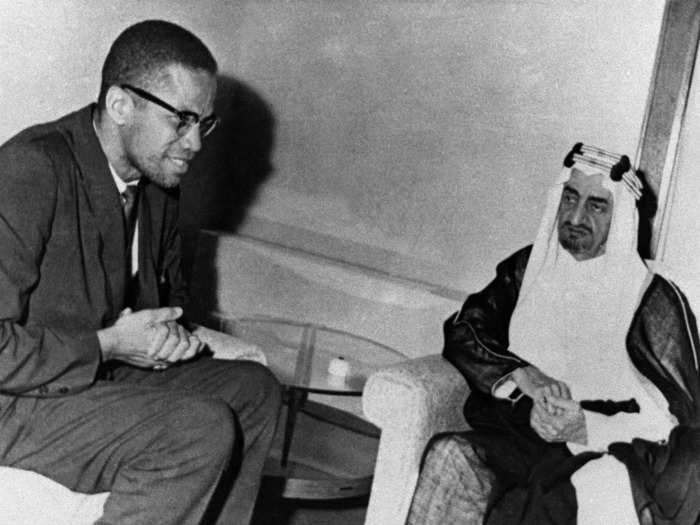

In 1960, Malcolm X's reputation continued to grow. He spoke with international leaders from Africa and the Middle East during the UN General Assembly.

Source: History Cooperative

He continued to make controversial statements: In 1962, he described a plane crash, which killed more than 100 primarily white people, as a "very beautiful thing."

Speaking to a crowd of about 1,000 people he said, "We call on our God—he gets rid of a hundred and twenty of them."

Sources: The New York Times, The New Yorker

He eventually crossed a line. After former President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, he said it was "the chickens coming home to roost," while referring to the death of black civil rights leaders and four girls killed in a Birmingham church bombing.

Source: The New York Times

He had been told by Elijah Muhammad to remain silent. After speaking out, he was punished with a three-month "silence" penalty.

Source: The New York Times

But trouble had been brewing for months. Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad grew apart and their relationship crumbled when he found out his mentor had had a number of sex scandals with different women.

Source: History Cooperative

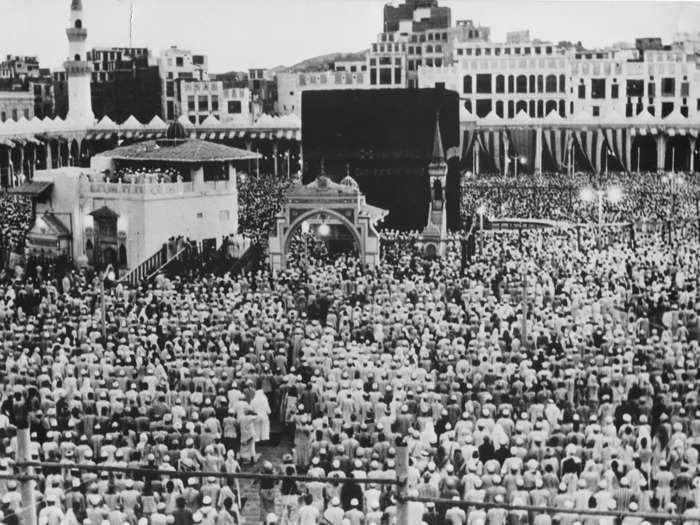

In late 1963, Malcolm X left America and spent two months in Africa and the Middle East. He traveled to Mecca, and saw Muslims of different races peacefully united. The experience was a life-changing moment for him.

Sources: The New York Times, The New Yorker

Of his travels, he wrote, "The true brotherhood I had seen had influenced me to recognize that anger can blind human vision." He decided race problems could be conquered without separatism.

Sources: History.com, AJC

He returned to America a changed man, renouncing racial separatism, and renameing himself El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. In March 1964, he officially left the Nation of Islam, and in June, he started the Organization of Afro-American Unity.

He also started the Muslim Mosque Inc.

Sources: The New York Times, History.com, The New York Times

He declared racism was his enemy, not solely white people. However, he maintained that his followers defend themselves "by any means necessary," at the launch of his new organization.

Sources: The New York Times, History.com, The New York Times

He tried to bring Muhammad Ali with him, but failed. After he left the Nation of Islam, Ali cut him off and said he would never speak to him again. In his autobiography, Ali said ignoring Malcolm X was one of the mistakes he regretted most in his life.

Sources: History Cooperative, Independent, Smithsonian

His relations did not improve with the Nation of Islam after he left. Malcolm told reporters the Nation of Islam was a money-making operation, and that Elijah was jealous of his popularity.

"Envy blinds men and makes it impossible for them to think clearly. This is what happened," he said.

Death threats were made against Malcolm X.

Sources: The Guardian, The New York Times, Al Jazeera, The New York Times

In June, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover sent a telegram to the New York office that read, "Do something about Malcolm X enough of this black violence in NY."

Source: CNN

Hoover in a meeting with President Lyndon B. Johnson, had also said about Malcolm X and King, "we wouldn't have any problem if we could get those two guys fighting, if we could get them to kill one another off…"

Source: The Daily Beast

Despite heavy surveillance by law enforcement, Malcolm X continued his rallies. He traveled overseas and spoke at universities. Compared to his early years, he was less aggressive. He was complimentary about King and said that not all white people were devils.

Sources: The New York Times, Smithsonian

On February 14, a week before his death, his Queens home, which was still owned by the Nation of Islam, was firebombed, as he and his family slept.

Sources: The New York Times, CNN

Right up to the end, Malcolm X remained open to changing his opinions. Three days before his death he said, "I'm man enough to tell you that I can't put my finger on exactly what my philosophy is now."

Source: The New Yorker

On February 21, 1965, he was due to speak at the Audubon Ballroom, in New York. Despite the firebombing, there was no police presence outside, and two officers were in another room.

This was despite his rallies usually warranting up to 24 officers. He also told his staff to not check people for guns as they entered, which had been protocol at his earlier meetings.

Sources: History.com, CNN

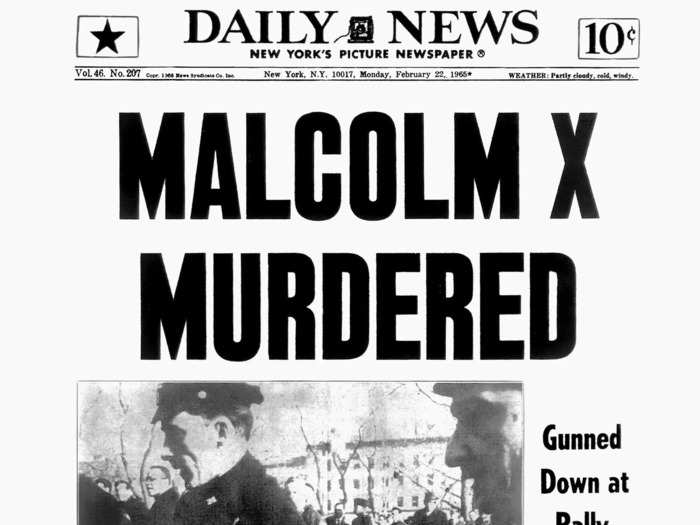

Before he could speak, he was shot 15 times. All 6 feet 4 inches of him fell like a tree, according to NPR. An ambulance was called, but it never arrived.

In his autobiography, he wrote, "If I can die having brought any light, having exposed any meaningful truth that will help destroy the racist cancer that is malignant in the body of America – then, all of the credit is due to Allah. Only the mistakes have been mine."

At the public viewing of his body, between 14,000 and 30,000 attended.

Sources: The Guardian, The New York Times, ABC News, History.com, Al Jazeera, NPR

He died at age 39.

Sources: The Guardian, The New York Times, ABC News, History.com, Al Jazeera, NPR

Three men, all members of the Nation of Islam, were later convicted of his murder — Mujahid Abdul Halim, Muhammad Abdul Aziz, and Khalil Islam. They were sentenced to life in prison, but Aziz and Islam claimed they had nothing to do with the murder.

Sources: The New York Times, The Guardian, CNN

Thousands grieved Malcolm X's death. But his reputation was far from exalted. At the time, Time magazine published an article calling him "a pimp, a cocaine addict and a thief" and "an unashamed demagogue."

While Ossie Davis said of Malcolm X, in his eulogy, "A Prince. Our own black, shining prince, who didn't hesitate to die because, he loved us all."

Sources: The New York Times, The New York Times, AJC

However, Malcolm X's significance and influence remained after his death. His life and speeches helped build the foundations for the Black Power movement, and advancing black consciousness in the 1960s.

Source: Al Jazeera

Along with his autobiography, Spike Lee released an Oscar-nominated film about his life in 1992, called "Malcolm X."

Source: The Guardian

Malcolm X's death was never properly investigated. And despite the convictions in his murder case, doubts lingered around whether the men who were convicted were actually responsible.

Source: The New York Times

In February 2020, 55 years after his death, Manhattan's District Attorney Cyrus Vance's office said it was reviewing whether or not to reopen his murder case, after the Netflix documentary released new evidence. While Islam, one of the convicted men, died in 2009, Aziz, who is now 81, hopes to clear his name.

Sources: The New York Times, NBC News

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement