- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- Russia is the world's largest producer of diamonds. I toured a mine in Siberia that produced 1.4 million carats of diamonds in 2018 - here's what it was like.

Russia is the world's largest producer of diamonds. I toured a mine in Siberia that produced 1.4 million carats of diamonds in 2018 - here's what it was like.

Russia is the world's largest producer of diamonds.

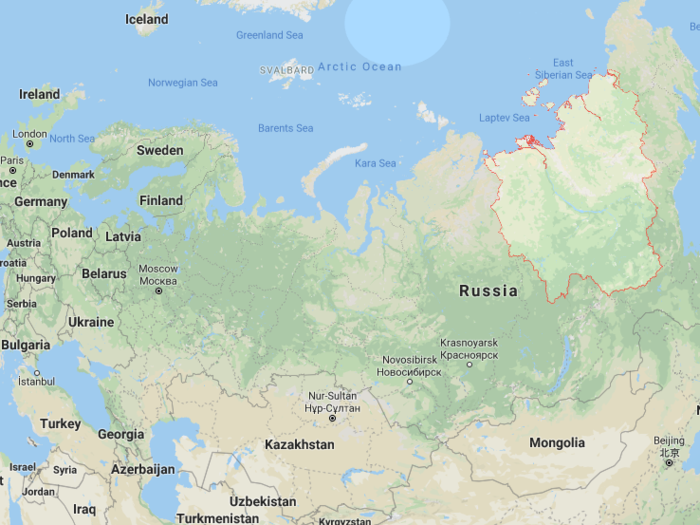

Most of Russia's diamonds are mined in the Yakutia region.

The Sakha Republic, also known as Yakutia, is a region in Siberia that's five times the size of France but has only about a million inhabitants.

On a recent trip to Russia, I spent three days in a diamond mining town in Yakutia.

Mirny is a town of about 40,000 people that's home to the headquarters of Russian diamond mining company Alrosa, the world's largest diamond miner by volume.

Ten of Alrosa's 12 mines are in Yakutia.

From Mirny, we had to take a one-hour flight to get to the diamond mine.

We boarded an Antonov AN-38-100, a small plane that can seat up to 27 people.

The diamond company has its own airline, Alrosa Airlines, which operates flights throughout Yakutia, as well as to cities like Moscow, St. Petersburg, Sochi, and Novosibirsk.

I was one of the last people to board the plane, which meant the only seat left was a rear-facing seat right against the cockpit.

There were no assigned seats; people threw their bags in a pile at the back of the plane and sat wherever.

The back of my seat was directly against a shared wall with the cockpit, so I had to sit with my back completely straight; it was not particularly comfortable.

It also meant I had a prime face-to-face view of all the miners who were on their way to start their shifts.

Some Alrosa miners who work at mines closer to Mirny take a bus to work every day, but those working at the more distant mines must take a plane. They typically work two-week shifts followed by two weeks off.

Also included in the group of people on the tiny plane were five other journalists and our two guides from Alrosa.

Through the dirty airplane window, I watched as we passed over forests, dirt roads, rivers, and lakes.

I'd never been in such a small plane. It was surprisingly loud.

After about an hour, we landed in what can only be described as the middle of nowhere.

We were surrounded by lots of trees, and that's about it. The temperature was noticeably cooler than in Mirny.

We passed through the tiniest airport I've ever seen.

It looked like a little white house. We walked through so fast that I barely noticed passing through the metal detector. I did notice a small waiting area with a tiny TV.

We walked straight through it to the other side, where a bus was waiting for us.

From the airport, it was about a 10-minute bus ride to our next stop: an Alrosa administrative building near the mine.

In the administrative facility, miners can have a meal in the canteen and change into their uniforms.

We borrowed some miners' uniforms, donning jackets and hard hats before we could venture into the mine.

The jackets were also to protect us from mosquitoes and biting flies that terrorize the region in the summer months, according to Alrosa employees.

We sat through a five-minute safety training where we were told to listen to Alrosa's employees, not get in the way of the miners, and stay away from the explosives storage area and the oxygen storage area.

We climbed into a massive orange truck that would take us to the mine.

Riding in the truck was extremely hot and extremely bumpy.

Fortunately, it was only about a 10-minute ride to the mine.

We got out first look at the mine from an observation deck built on one side. The open-pit Botuobinsky mine spirals down about 426 feet, and it's about 1.2 miles long at its widest point.

The mine, which has been in operation for about five years, was created by first using explosives to get rid of the empty soil on top. Then came the excavators and trucks to haul out the soil and the kimberlite ore, which is what contains the diamonds.

The Botuobinsky mine will continue to get much deeper; it's expected to operate for another 15 years or so.

Once the open-pit mine has been depleted, Alrosa will turn it into an underground mine and continue operations below the surface.

It takes a truck 40 minutes to take a round trip to the bottom of the mine and back.

Some of the trucks are carrying empty soil to dump nearby, while others are taking kimberlite ore to the factory for the ore enrichment process, to separate the rough diamonds from the other stones.

The miners excavate roughly five times more soil than ore, so most of the soil has to be discarded.

The trucks can carry about 90 tonnes — or almost 200,000 pounds — of soil or ore.

This truck was well over 16 feet tall.

I got the chance to hop up inside one of the trucks alongside an Alrosa miner. I don't speak Russian and he didn't speak English, so it was a quiet ride.

The driver is one of 47 Alrosa miners who work in the Botuobonskaya at any time of day. They work two-week shifts of 11 hours per day — some during the day and others at night.

While I couldn't get a good look at the other miners driving trucks, an Alrosa employee told me that that they were all men. Women typically drive passenger trucks for the workers, but not the trucks that carry ore — although a couple of women are currently in training to drive the ore trucks, I was told.

The miner drove me over to get a closer look at the excavation truck that dumps soil and ore into the back of his truck.

Each excavator bucket holds about 30 tonnes — more than 66,000 pounds — of soil or ore.

And one truck can be loaded up with three buckets full of soil, or more than 200,000 pounds.

In a 24-hour period, about 60,000 metric tonnes — or more than 66,000 US tons — of soil and ore are extracted from the Botuobinskaya mine.

Botuobinskaya is not the only diamond mine in the vicinity. A short drive away is the Nyurbinsky open pit, which is a much deeper 1,181 feet.

Because of its depth and steep sides, the Nyurbinsky mine was more impressive to look at than Botuobinskaya. But the prospect of driving down those narrow dirt roads was a bit daunting, so I didn't mind just looking.

Alrosa found another kimberlite ore pipe nearby where they'll begin operations in the next couple of years, an employee told me.

After our tour of the diamond mine, we got a closer look at some kimberlite ore, the igneous rock that can contain diamonds.

Sadly, I didn't spot any diamonds in my handful of kimberlite ore. After it's mined, the ore must go through an ore enrichment process to separate the rough diamonds from the other rock formations.

To my untrained eye, the ore seemed like an especially crumbly pile of dirt and rocks.

After spending a couple hours at a diamond mine, I was blown away by what it takes to produce the gems the world loves so much.

Each metric tonne of ore, which equals about 2,200 pounds, only contains up to 6.2 carats of diamonds. And that's not to mention the hundreds of thousands of pounds of ordinary soil that doesn't contain any diamonds.

Still, the world currently has a surplus of rough diamonds, as The New York Times recently reported. Prices stay steady, however, because of the many middlemen a stone must pass through before it's sold, from miners to polishers and cutters to traders and jewelers.

So while a diamond is coveted because of its purported rarity, it was clear that its value also lies in the sheer effort and manpower it takes to get it from the permanently frozen ground in Siberia to a glittering piece of jewelry.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement