- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- Living in outer space can cause these 9 weird changes to your body

Living in outer space can cause these 9 weird changes to your body

Your body fluids shift.

Your face looks different.

With less gravity, a lot of liquids move toward and into your head — so your face looks puffy.

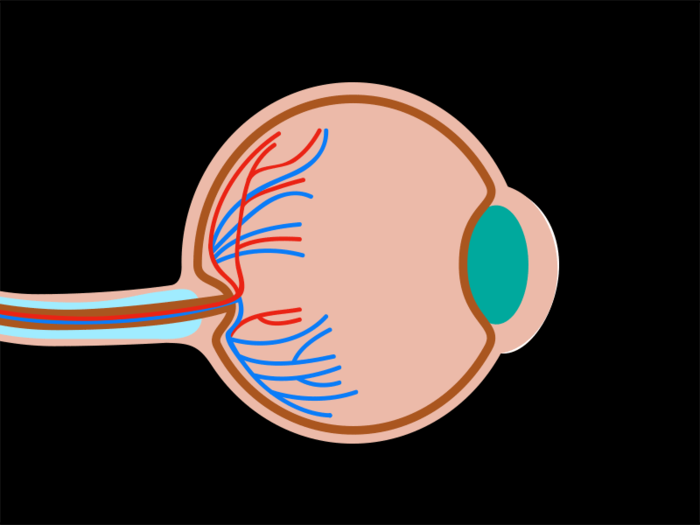

Your sight could change.

For the same reason that your face puffs out, your vision might get worse due to pressure changes in the brain. Fluids near the optic nerve can push on the back of the eyeball.

Deep-space radiation might also promote cataracts and impair eyesight. Even high-flying commercial-airline workers face that risk because of the thinner atmosphere.

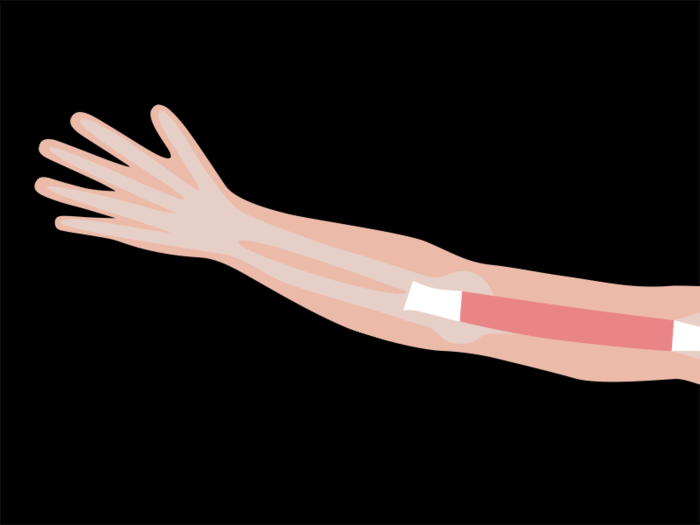

Your bone density can change.

If you don't exercise while in space, you'll lose about 12% of your bone density. Researchers are still trying to understand why this happens, though microfractures in bone caused simply by walking around on Earth seem to be important to maintaining bone health.

You get taller — until you get back to Earth.

Since gravity isn't pushing you down, fluid-filled discs between each of the bony vertebrae in your spine don't get compressed, stretching your height by about 4%. After Scott Kelly's time in space, he returned 2 inches taller than his twin brother. But returning to Earth-like gravity reverses that effect.

Your muscles can shrink.

You don't need muscles when you're weightless, so they atrophy and absorb the extra tissue. This is why physical exercise is a part of every astronaut's schedule. However, nothing seems to maintain muscle mass better than the strain of living in the gravity found at Earth's surface.

You'll be sleepy.

You'd probably be sleep-deprived. Most astronauts only get 6 hours a night because sleeping in space feels weird.

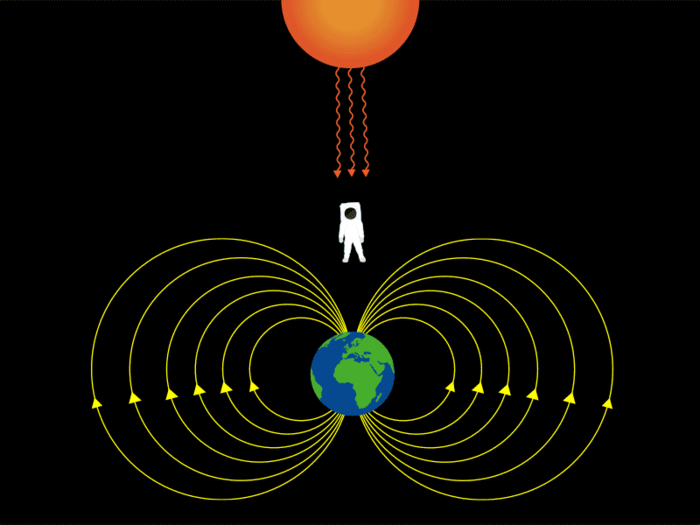

Your cancer risk increases.

Radiation bombarding your body outside of Earth's protective magnetic field can increase your risk of getting cancer.

NASA currently limits male astronauts' lifetime radiation exposure to 3,250 millisieverts, which is equivalent to about 400 CT scans of the abdomen. Female astronauts typically have more tissue that's susceptible to radiation, so their lifetime limit is 2,500 mSv.

Animal research suggests this threat could be worse in deep space than previously thought, though studies involving humans are needed to confirm that's also true for astronauts.

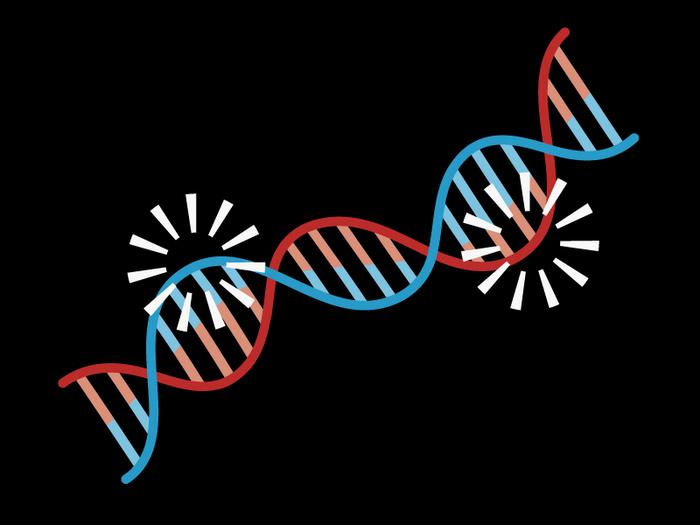

Your genetic code behaves differently.

DNA is life's basic blueprint, and genes — much like words in a cookbook — spell out the specific recipes to keep us alive. However, it's equally important when and how much those genes are expressed, or turned on and off. A lot of that has to do with a person's environment.

The Twins Study found that about 7% of Scott Kelly's genes expressed a bit differently after a year in space than they did on the ground, and didn't return to normal (or at least not quickly). The real-world ramifications of this are still being explored.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement