- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- Inside the world's toughest sailing race, where crews endure chaotic seas and cramped quarters to sail around the world

Inside the world's toughest sailing race, where crews endure chaotic seas and cramped quarters to sail around the world

Only the toughest, most experienced sailors are capable of participating in the race. On the longest legs, competitors spend close to a month at sea, running the boat 24 hours a day.

The boats are designed for speed — not comfort — so it can be a wet, bumpy ride when the weather isn't cooperating. Each boat is 65 feet long and built to withstand punishing ocean conditions.

"It's an experience," Carlin said. "It can be pretty bleak and if you're on deck, you're getting hosed by waves and the salt water gets into your skin and you get calluses and you get rashes and it's... Yeah, it's actually not that appealing when you, when you think about it."

This year's race started in Alicante, Spain in October 2017.

The fleet completes the journey in 11 parts. The sailors are currently getting some rest during their ninth stop. They're in Newport, Rhode Island after 15 days at sea. At the end of the most recent leg, team MAPFRE was in the lead with 53 points.

The 2017-2018 edition of the race is set apart by a new rule: it's the first year that women must be included in each of the sailing teams.

The event is highly competitive. The boats are often just minutes apart from each other at all times as they travel over 15,000 miles and spend weeks at sea.

The boats can reach speeds of up to 25 knots, or almost 30 miles per hour, in prime sailing conditions. The vessels can also "surf" down large waves, breaking 30 knots.

The ships can cover around 500 nautical miles in 24 hours in good sailing conditions if the crew is "sending it," Carlin said.

On each boat, the 10 members of the crew have specific job functions.

The navigator's job is to set the route to maximize optimal weather and wind conditions.

But the skipper, or captain, always makes the final decision, Carlin said.

An onboard reporter like Carlin is assigned to each boat to document the trip for the Volvo Ocean Race organization. They live and sleep with the crew, but aren't allowed to help sail in any way.

The reporters train their pens and cameras on the sailors at all times — even when the team is grumpy and exhausted, Carlin said.

Leg 7 of the race requires the sailors to round Chile's infamous Cape Horn, a peninsula that has proven to be a graveyard for ships for hundreds of years. That's where teams experience some of the most vicious weather.

"It's a pressure cooker environment where every sail change, every decision, every little movement on the boat counts for winning or losing," Carlin said.

But that's all part of the challenge. Many sailors see the race as a test of will between them and sea.

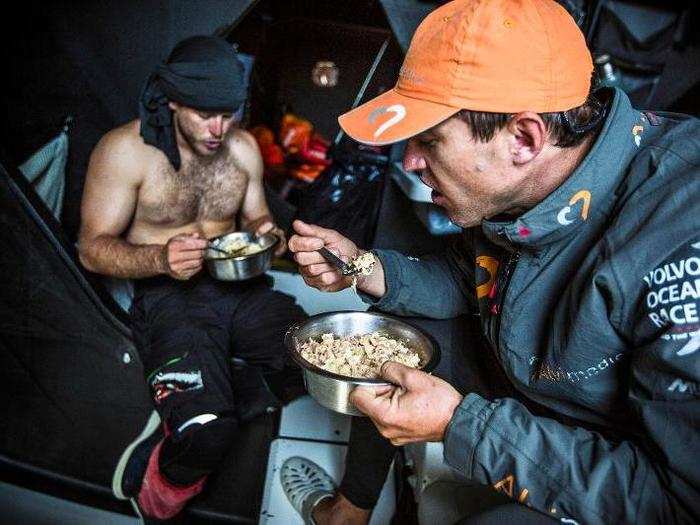

Life on board the ship isn't easy. The sailors bring minimal clothing — just what they need to stay warm in cold and wet conditions. All the food they eat is pre-packed and freeze-dried.

There's nothing resembling bedrooms or even traditional beds on the ships.

The sailors usually only sleep for 3 or 4 hours between shifts, Carlin said.

"I suppose the best way to describe it is sitting in a one-bedroom apartment with 10 people, a bucket for a toilet, your freeze-dried meal comes out of a bag, and then you go to sea for three weeks," Carlin said. He added that most people just go to the bathroom off the back of the boat.

"It's either freezing cold or super hot," Carlin added. "There's no windows you can open, the smells get pretty funky, and you're always tired, and you haven't slept that much."

In the area near the equator, there's not much wind, so the sailors get a lot of downtime to rest and do repairs on the ship. They refer to it "the doldrums."

With little wind in that area, the boats can usually only travel around 60 miles in a day, a pace Carlin said can feel "pretty painful".

While life during the race is mostly grueling, the sailors still find time to have fun.

One of the rituals that sailors practice when they cross the equator is a sacrifice to King Neptune, the god of the sea. Teams' approaches differ, but the ceremony usually involves the skipper dressing up as Neptune and covering a rookie sailor — or other team member — in food, paint, or something else gross.

As hard-core sailors, each competitor lives for the race's sublime moments on the open ocean.

But the Volvo Ocean race is a team sport. "You cannot be an individual on these teams," Carlin said. "You're not gonna survive, you won't be accepted."

"This is about being a team and working together and getting the best out of it," Carlin said.

The fleet leaves Newport on May 20 to cross the Atlantic towards Cardiff, Wales.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement