- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

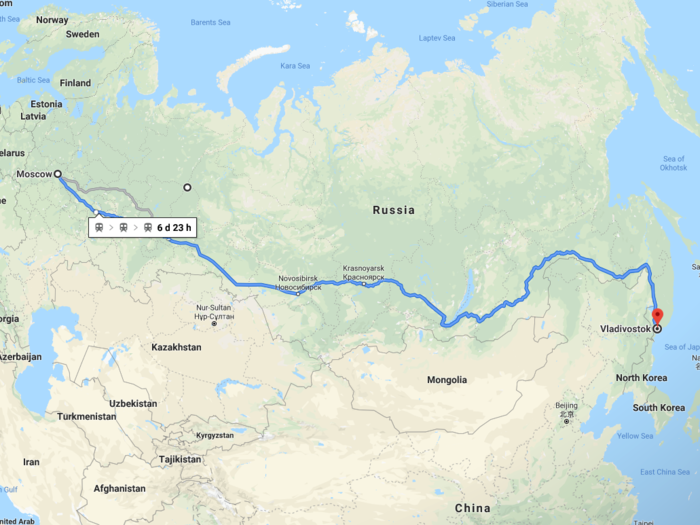

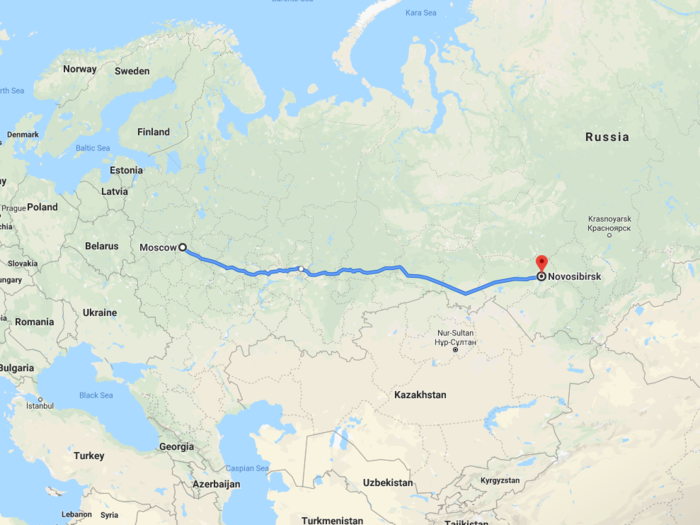

- I rode the legendary Trans-Siberian Railway on a 2,000-mile journey across four time zones in Russia. Here's what it was like spending 50 hours on the longest train line in the world.

I rode the legendary Trans-Siberian Railway on a 2,000-mile journey across four time zones in Russia. Here's what it was like spending 50 hours on the longest train line in the world.

With a total length of 5,772 miles, the Trans-Siberian Railway is the longest in the world.

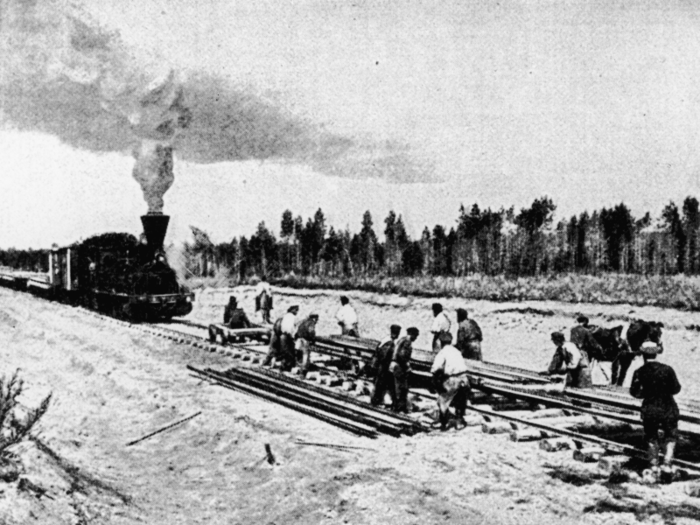

The railway took 25 years to build.

Construction on the Trans-Siberian Railway started in 1891 and was completed in 1916.

Builders had to to deal with hostile weather conditions and building train tracks on permafrost and mountainous terrain.

My journey on the Trans-Siberian began in Novosibirsk, a city of 1.6 million people in Siberia.

I'd arrived in Novosibirsk after a three-hour flight from the diamond mining town of Mirny.

Novosibirsk, the largest city in Siberia and the third-largest in Russia, is about 267 miles (430 kilometers) from the southern border with Kazakhstan.

Before I got on the train, I had to stock up on some essentials for the journey, so I headed to a grocery store right across the street from the train station.

I had read multiple blog posts with recommended packing lists for the Trans-Siberian Railway, so I had a pretty good idea of what I needed.

I bought slippers, bottled water, tea, dried noodles, granola bars, baby food (that was not on the lists; I just like it), chocolate, and what I thought was oatmeal but turned out, unfortunately, to be buckwheat.

I also grabbed some hand sanitizer, tissues, and baby wipes, which I'd read are essentials on the Trans-Siberian railroad.

Terrified that I might miss my train, I arrived at the Novosibirsk train station an hour before my train was scheduled to leave.

The more than 322,900-square-foot station is one of the largest in Russia.

I had some trouble finding the correct platform, but after frantically querying multiple people, "Trans-Siberian?" and getting gestures in the right direction, I eventually found it.

Train attendants were standing outside each train door, checking tickets. I found my carriage, showed my e-ticket to the attendant, and hauled my small yet deceptively heavy suitcase up the steps onto the train.

The train corridor was narrow. In order for two people to pass, they'd both have to turn to the side.

I looked for my compartment, No. 26, where I was assigned an upper bunk.

The compartment was a bit smaller than I had expected. I had a second-class ticket, which I'd bought about three weeks in advance for $148.

I'd considered buying a first-class ticket because it wasn't much more expensive, but first-class tickets either weren't available on this train or they were sold out. The website wasn't clear.

I was the last member of my four-person compartment to arrive. The other passengers were three Russian men who appeared to be in their 30s. Later, I would learn they were all in the military and taking the train home from work.

The three men, one of whom was not wearing a shirt (it was hot), looked at me in alarm as I appeared in the doorway of the compartment.

I waved. "Hello!"

They immediately stood up, greeted me in Russian, and then headed for the door. One of them helped me put my suitcase up above the door, and then all three of them went out and stood in the hallway, apparently to give me my space as I got situated.

I put my other bag up on the top bunk and then sat down, feeling very hot and wondering if there was air conditioning in this train. After a few minutes, my compartment mates came back in and introduced themselves as Aleksandr, Sergey, and Konstantin.

The bunks in our compartment were a little wider than half the size of a twin bed. Near the door, small ladders unfolded to allow the upper bank passenger to climb up. Even with the ladder, clambering up to my bunk wasn't particularly easy or graceful. I hoped I wouldn't have to pee in the middle of the night.

There didn't seem to be any clear etiquette for whether I should be able to sit on the bottom bunk — as it was someone's bed — but my three Russian friends made it clear I could sit there whenever I wanted.

After the train got moving, the air conditioning kicked on, although it wasn't very strong.

The bottom bunks each had a power outlet.

The upper bunks only had USB ports, but that was fine with me, as I only really needed to charge my phone.

A pillow and blanket were waiting for me on my bunk when I got on the train, and about an hour in, the attendant came around and handed out pillow cases, sheets, and duvet covers.

The mattress was about three inches thick and reasonably comfortable.

The attendant also handed out a hygiene kit that included a pair of flimsy blue slippers, a toothbrush, toothpaste, and a wet wipe.

I already had all of these things with me, but it was good to know I had back-ups.

Next to the bathroom was a garbage bag and chute.

The bag was emptied and replaced regularly.

The bathroom was cramped and far from luxurious.

When I flushed, I saw the the contents of the toilet fall directly onto the tracks rushing by below.

The unspoken rule was that toilet paper should be thrown in the trash instead of in the toilet, but not everyone abided by that.

The sink was tiny, maybe slightly larger than an airplane sink. The first time I used it, I squirted soap all over my hands and then tried to turn the red knob. Nothing happened. Assuming it was broken, I rubbed the soap off my hands with a paper towel and went back to the compartment.

I alerted my three new Russian friends that the bathroom sink was broken. With an amused look on his face, Aleksandr shook his head and gestured for me to follow him back to the bathroom. As it turned out, to turn on the sink you had to push up on a small lever jutting out from right underneath the faucet, which did not seem obvious at all.

While the bathroom was bare-bones, it was cleaned regularly and remained stocked with toilet paper, hand soap, and paper towels throughout my 50-hour journey.

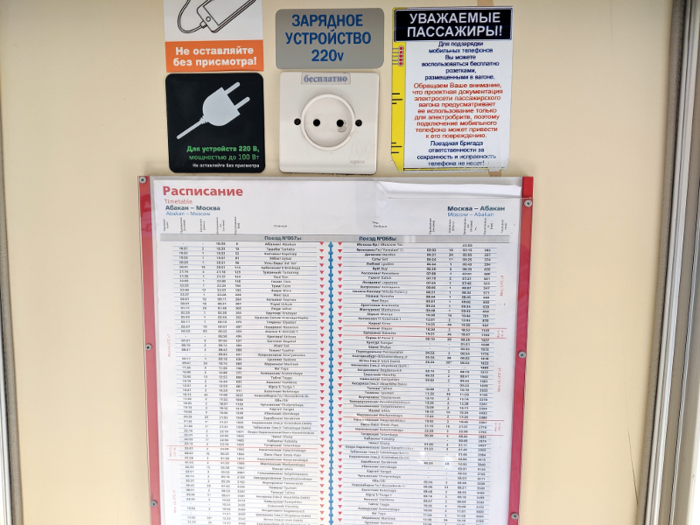

In the middle of the hallway was a power outlet and a sign listing all the stops on the way to Moscow, including the exact time of the stop and how long the train would sit at the station.

In the smaller towns, stops were often only two to five minutes long, just enough time for some passengers to get on and off.

Other stops were up to 40 minutes.

I wore my trusty mint-green slippers throughout my entire journey on the train. They were convenient because I could easily slip them off to climb up on my bunk, and back on when I went to the bathroom or for a stroll in the corridor.

I also wore the same clothes the whole time.

Gross? Yes. But I didn't want to change clothes in the cramped bathroom — partially in fear that the train would jolt and I'd fall into the toilet — and as nobody else seemed to change clothes in my compartment, I didn't want to be the weird American exposing myself to everyone.

At the other end of the train car from the bathroom was the most underrated part of the train journey: the samovar, or hot water kettle.

The samovar has an endless supply of hot water for tea, noodles, instant coffee, or whatever your heart desires.

Throughout my journey, I drank more tea than I ever had in my life — mainly because I was bored — but also because I didn't feel like I'd brought enough drinking water. (I brought three liters.)

As luck would have it, toward the end of my time on the train, a few hours before I got to Moscow, I learned there was a faucet for drinking water near the attendant's compartment.

I was most excited for the scenery I would see on my train journey.

After we left Novosibirsk, the landscape turned into picturesque, gently rolling hills and forests.

Here and there we passed small towns and villages.

Siberia is home to about 36 million people, or roughly 25% of Russia's population, according to multilingual Russian publication Russia Beyond.

Almost every house I saw had a garden in the backyard.

At about 6:30 p.m., an hour and a half after I'd boarded the train, the attendant came around to take orders for dinner.

At first, I politely declined because I had eaten just before I got on the train. It was also because I'd heard the Trans-Siberian train food was overpriced and mediocre, but I did plan on trying it at some point.

But Aleksandr, Sergey, and Konstantin seemed concerned and told me — via Google Translate — that it was included in the price of my ticket, which I didn't know. I went ahead and ordered the chicken dish because that's what everybody else ordered. (The other option was beef.) It came with a type of buckwheat, which I learned is a popular Russian dish called grechka.

The food was indeed mediocre. It was hot, but the chicken didn't have much flavor and the grechka was even more tasteless. I subsisted on snacks and instant noodles for the rest of my journey.

Dinner also came with an additional little box with a water bottle, some packaged salami, a cookie that was something like an Oreo knockoff, and plastic utensils.

The salami actually wasn't bad, but the fake Oreo did not appeal to me. I meant to try it later, but it must have gotten thrown away at some point.

While we ate, I chatted with my three new friends through Google Translate. I'd read that I wouldn't have cell phone service on most of the train journey — nor Wi-Fi — so I downloaded the offline version of Google Translate for Russian. It ended up being a lifesaver.

Through our Google Translate conversation, I learned that Aleksandr, Sergey, and Konstantin would only be on the train with me for about eight hours. They were getting off at Omsk, where they lived, at about 1:00 a.m.

I told them I had just come from Yakutia and they seemed shocked, although Alexander said his uncle lives there.

One of the first things they asked me was: "Why did you not take a plane to Moscow?"

I tried to explain that it was for the adventure! The experience! They didn't get it.

I drank some tea with water from the trusty samovar down the hall.

The tea mug is made up of a traditional Russian metal tea-glass holder called a podstakannik, which used to be seen in taverns but is now primarily used on long-distance trains.

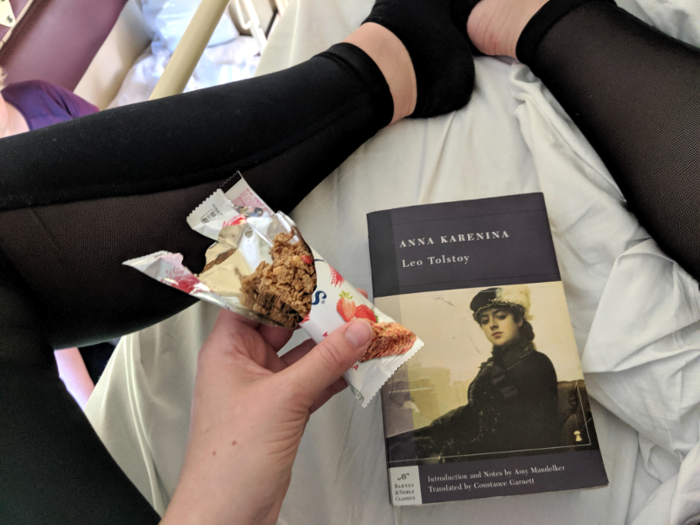

After a day of airplanes, taxis, and making sure I made it on the train, I was glad to have some time to relax on my bunk. There wasn't quite enough room for me to comfortably sit up, so I laid down against my pillow to read.

I didn't plan on going to bed early, but the gentle rocking of the train was unexpectedly soothing, and I was soon asleep.

I woke up at about 12:30 p.m. when my bunkmates got up and started packing up their things. At 1:00 p.m., the train stopped in Omsk, where they were to get off. We said our goodbyes and then I promptly went back to sleep for another seven hours or so.

That being said, I'm not really sure how long it was because the time zone changed sometime in the night.

When I woke up the next morning, I had three new traveling companions in my compartment, all Russian: two middle-aged sisters traveling together and a middle-aged man traveling by himself. I said hello and then ate a granola bar for breakfast while reading (what else?) Anna Karenina.

Later, I briefly chatted with my three new companions, mostly via Google Translate, although the man and one of the women spoke a little English.

"You're not afraid to travel in Russia alone?" one of the sisters asked me.

I shrugged and said, "Not really."

"Because we are," she said. "Russia is a dangerous place."

The man said it would be better to travel on the train with a friend, and I thought he was probably right, although more for the company than for safety. I never felt unsafe on the train.

I went to check out the dining car, which I'd heard was only two cars over.

I didn't plan to eat in the dining car, because I'd read that the food was overpriced and not very good. If it was anything like the chicken-and-buckwheat meal I'd been served the night before, I wasn't too keen to try it.

The dining car was nothing fancy.

I tried to sit down at one of the tables and read my book, but I was sternly ushered out by one of the train staff, so I deduced that you had to actually order something in order to hang out there.

Beer and wine were sold at the small bar.

A quick glance at a menu showed me that I could get the same chicken-and-buckwheat meal from the night before in the dining car. Most of the dishes were some combination of beef, fish, potatoes, cabbage, and buckwheat.

Most of the main dishes were between 600 and 800 rubles, or about $9 to $12, which I found to be relatively pricey. Most of my meals in Russia so far, even in Moscow, had cost between $5 and $8.

The two sisters and the man were on the train with me for about 18 hours total, I believe, but time seemed to have lost all meaning at that point.

In Yekaterinburg, a city about 27 hours from Moscow, many people got on and off the train.

A tour group of about 10 people arrived in my car in Yekaterinburg, and to my surprise, they were all English-speakers, some from Australia, some from the UK, others from Canada.

I had yet another set of new compartment buddies, this time an Australian couple named Ian and Astrid who appeared to be in their 60s, and a Russian woman named Marina, who told me via Google Translate that she was 60 years old, retired and living in Moscow, and receives a pension of 1,000 rubles (about $15) per month.

After my first night on the train, I was desperately wishing for a shower. Some Trans-Siberian trains have showers in their first-class cars, but as far as I knew, my train didn't even have a first-class car.

Each morning and evening, I gave myself a wet-wipe bath and brushed my teeth in the bathroom. It helped a little, but I still felt gross for the majority of the trip.

My second day on the train dragged by. It didn't help that we crossed four time zones, so it felt like I was going back in time even as I wished for it to move faster.

I spent some time talking to the Australian couple, Ian and Astrid. It was nice to be able to talk to someone after so many hours of Google Translate-only communication. I learned that they lived on a farm near Brisbane and were two weeks into a 10-week trip across China, Mongolia, Russia, and Europe.

I spent a lot of time on my favorite pastime: pacing up and down the corridor drinking tea.

It was a way to get a tiny bit of much-needed movement, and I got a glimpse into the other compartments.

Each compartment was like a peek into a distinct little world. In one, a woman was lying down reading. In another, a family was eating ham sandwiches and drinking tea out of the same mug I was.

I also napped a lot.

Thanks to our train attendant, a middle-aged blonde woman who wore a long, light-blue dress and glasses, the carriage stayed clean throughout the journey.

Every few hours, it seemed, she would vacuum the hallway and the individual compartments, clean the bathroom, empty the trash, and wipe down various surfaces in the hallway.

She would also meticulously straighten the pink-and-white striped rug that spanned the length of the train car.

The scenery eventually got pretty monotonous. Yes, it was beautiful — all greenery, trees, wildflowers, and sunshine. But there wasn't much variety.

The second afternoon, there was a brief thunderstorm, which an exciting change of pace. But then back to trees and sunshine.

But every once in a while, the trees would open up and I'd get a glimpse of something new, like a sparkling river.

People were floating down the river and camping and swimming on its banks.

We passed some cute riverfront houses.

I wondered how much they would cost and who lived there.

I didn't sleep as well my second night on the train as I had the first night because Marina snored louder than anyone I've ever heard, and Astrid complained about the snoring louder than anyone I'd ever heard.

A little over six hours before the end of the journey, we had one of our final stops in the town of Danilov, a little over 200 miles (333 kilometers) from Moscow.

A couple of small shops at the station were selling cookies, chips, sandwiches, ice cream, and other snacks.

Local women were selling fresh strawberries and cherries on the other side of the train station gate.

I didn't buy any.

After more than 40 hours on a train with little physical activity, I didn't have much of an appetite.

A few stray dogs were hanging out on the platform, soaking up the sunshine as well as attention from train passengers.

The last six hours were uneventful. I read a little bit, slept a little bit, and dreamed about sleeping in a real bed.

Just before 5 p.m., we arrived in Moscow right on schedule, 50 hours after we'd departed Novosibirsk.

I had never been so happy to get off a train before, but at the same time, I was sad it was over.

It was my first time riding a sleeper train, and getting to travel more than 2,000 miles on one across Russia was a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

By the time I got back to Moscow, my 50-hour train journey had spanned more than 2,000 miles across four time zones.

Compared to the rush and constant movement of the other 10 days I spent in Russia, the weekend on the Trans-Siberian was a welcome chance to relax, catch up on sleep, read, and just be alone with my thoughts.

Chatting with locals who were absolutely perplexed as to why I would take the Trans-Siberian for fun was an added bonus.

Although the train ride was far from luxurious, I wouldn't hesitate to do it again with a few key changes. An obvious one is that it would be more enjoyable traveling with a friend (or three friends so we could have a compartment to ourselves).

I would also bring a better variety of snacks. The Australian couple brought some meat, cheese, and bread to make sandwiches, as well as some fruit. My granola bars and dried noodles got old very quickly.

And finally, I would try to choose a route with more varied scenery if possible — or time my naps better. At one point, the Australian couple told me we passed through the Ural Mountains and got some stunning mountain views. I, of course, was napping.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement