- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- I followed New York City 'deathcare' workers as they collected the bodies of people killed by the coronavirus, and saw a growing, chaotic, and risky battle

I followed New York City 'deathcare' workers as they collected the bodies of people killed by the coronavirus, and saw a growing, chaotic, and risky battle

Marmo is a 49-year-old native of Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, with an unmistakable accent. I met him outside the Daniel J. Schaefer Funeral home: one of a handful of mortuary service locations he owns across the city.

When the funeral home doors opened, the staff pulled up N95 face masks and put on surgical gloves.

I'd brought protective gear, too, to reduce my risk of exposure as much as was reasonably possible while shadowing Marmo and his crew. I also packed a fresh change of clothes for after I finished the assignment.

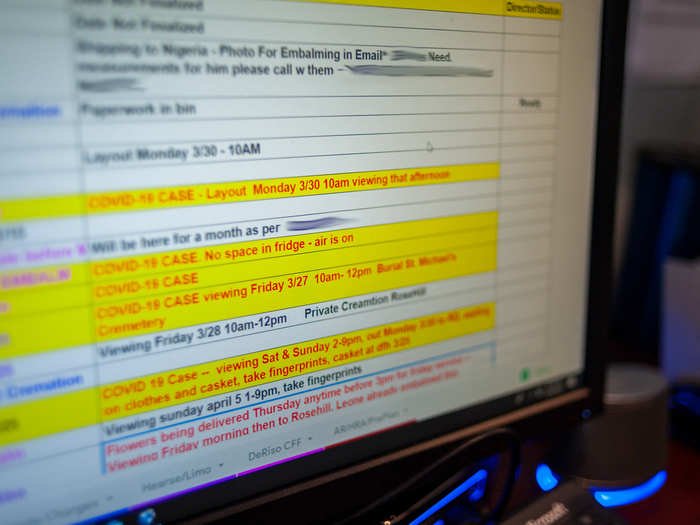

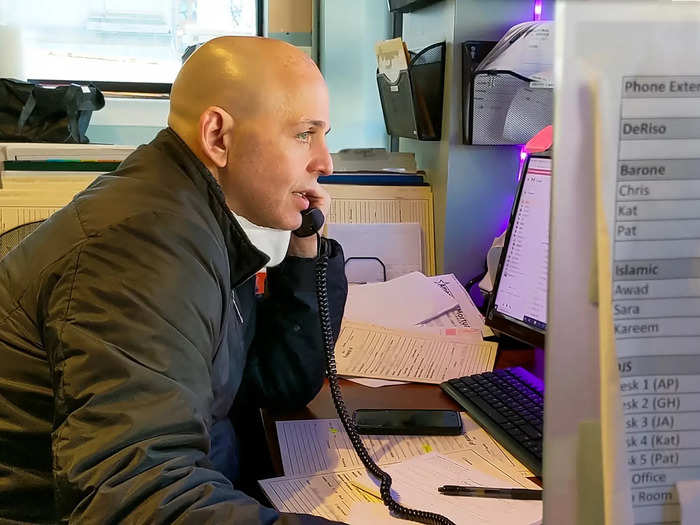

Phones started ringing almost immediately after the home opened at 9 a.m. — families called to seek assistance, while other funeral-home locations tried to work through logistical challenges brought on by the pandemic. An employee said they'd been working 12-hour days and apologized for the chaos.

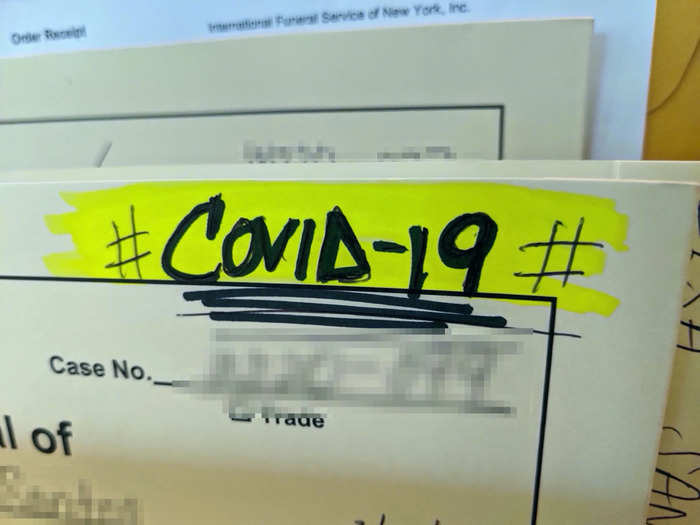

Space for the deceased is waning. Prior to the pandemic, International typically had 40 open cases on its roster. By the end of the day I visited, International had taken on 11 new COVID-19-confirmed bodies for a total of about 22. That's in addition to all the other non-COVID-19 decedents families had asked the company to handle.

The caseload is only part of the story, though, as it does not include completed cases — i.e. bodies buried or cremated — only those awaiting a final resting place.

By Saturday, International had 43 COVID-19 cases. By Monday, it had 71. That brought International's total to 143 cases (including deaths not caused by COVID-19).

Within the first hour International opened on the day I visited, a family called about a loved one who'd died from complications related to COVID-19. Her body was at a hospital in Brooklyn and needed to be picked up.

We piled into a van staff call "Big Black." It's discreet by design: Few people would want to see a "BODY REMOVAL SERVICE" label emblazoned on its side.

Still, there is a grim placard in the front window to ensure the car doesn't get ticketed or towed.

A box of body tags sits in the front of the car.

The van has a pneumatic lift and can accommodate multiple large bodies at a time.

As New York City's coronavirus crisis grows, employees are now filling it up regularly.

As the rate of COVID-19 patients outstrips hospital resources, more and more bodies are going to morgues. The city has requested emergency mortuary assistance from FEMA, but hospitals have already begun to expand capacity. At least one hospital is using a 53-foot refrigerated semi-trailer to temporarily hold overflow.

"At the rate people are dying, I think [hospitals] are doing a good job even thinking about refrigeration," Marmo said. "With a week's notice, they've prepared pretty well."

When we arrived to pick up the woman's body, we received a temperature check at the hospital entrance to ensure no one had a fever. The group moved past security into an office area and notified the staff that they would remove the body from the morgue.

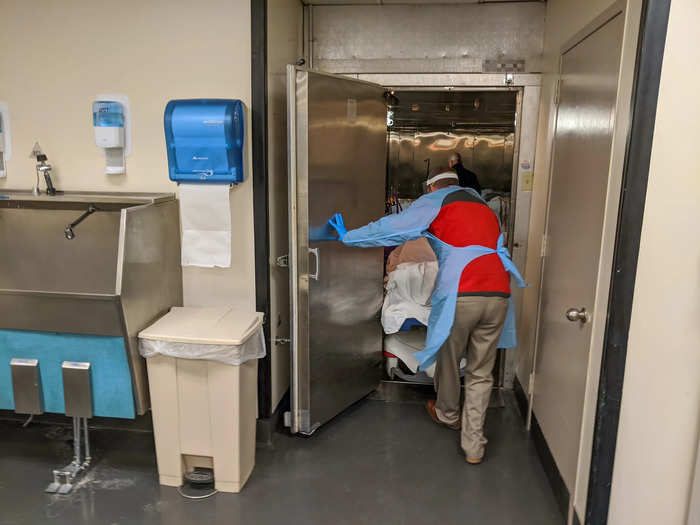

Marmo wheeled out a gurney while his colleague put on two pairs of surgical gloves, a plastic gown, and a face shield. Typically, far fewer precautions are needed.

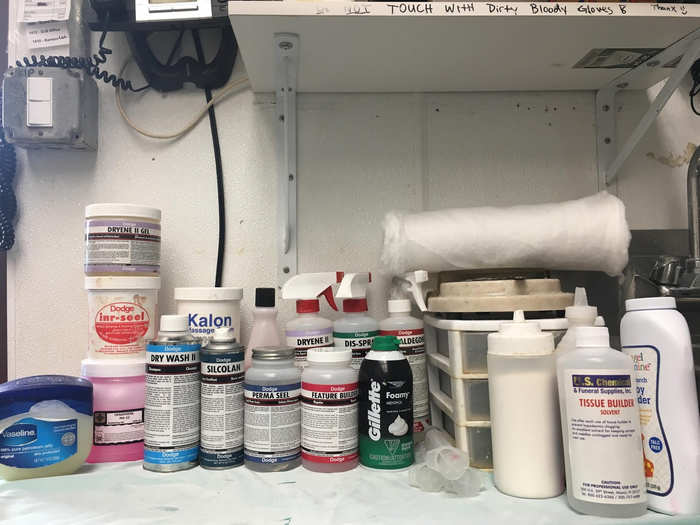

But these days, Marmo's crew brings along a lot of personal protective equipment for workers who have to get close to bodies as they move them onto gurneys, inside boxes, and into the van.

Some people in the deathcare industry have already contracted COVID-19, though from where is not clear. "A friend of mine is on a ventilator right now, he's a funeral director," Marmo said. "That guy's fighting for his life."

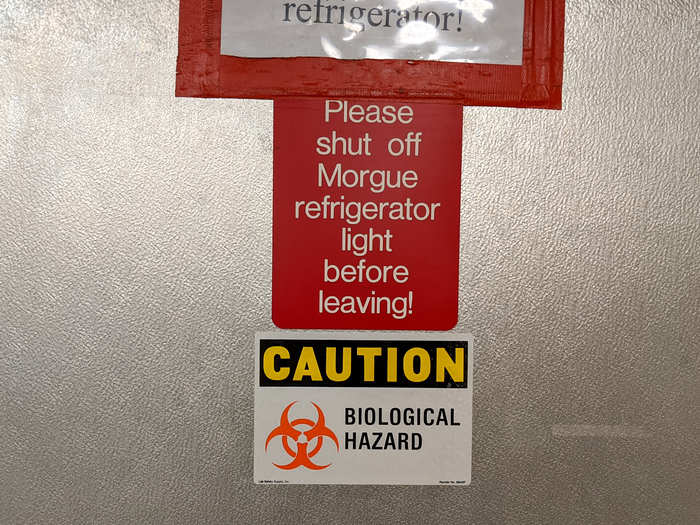

For removals, Marmo said he used to send one worker and a $5 bill to hand to a security guard. The guard would "open the refrigerator door, help verify a person's name, and help you move the body from the refrigerator," he said. Now he sends two workers because many security staff are too afraid to get close to COVID-19 bodies.

Marmo's team also keeps industrial disinfectant spray in the van, since it almost certainly kills the coronavirus.

Marmo and his assistant located the body in the hospital morgue, sprayed down the bag (especially its zipper) with disinfectant spray, and opened it to verify the person's identity.

They draped a disinfectant-soaked paper towel over the mouth to ensure any material inadvertently emitted from the lungs — which harbors the disease — would be at least partly blocked.

After a graceful slide of the body bag onto the van's gurney, the team wheeled their precious cargo out of the hospital, into the van, and drove off to a funeral home.

They took the body to De Riso Funeral Home in Brooklyn, a different location than the one we'd started at. As I began to wonder how they'd move the body from this parlor to a basement below...

... Marmo's colleague activated a hidden pneumatic lift, which popped out of the floor.

A narrow staircase led to the basement below, where embalmed bodies awaited dressing for funeral services.

Marmo and his colleague moved the woman's body into a refrigerator unit with temperatures between 40 and 45 degrees Fahrenheit. That slows decomposition prior to embalming. Then they carefully yet speedily dressed the embalmed body of a man before leaving.

"I don't ask anybody on my staff to embalm them because I don't want the responsibility of them getting sick on my on my hands," Marmo said of the COVID-19 patients he picks up.

Driving around the city was surreal in many ways. The streets, for one, were empty even during morning rush hour on a weekday. "The only thing on our side is no traffic. It helps us be more efficient. The demand is so much greater now," Marmo said.

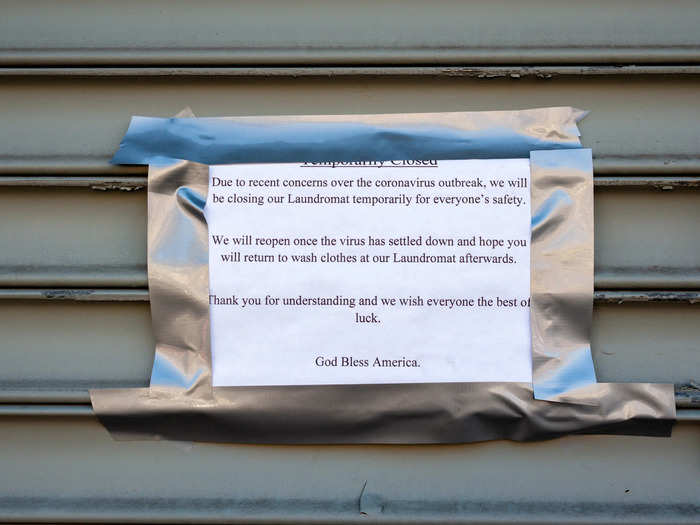

The city ordered non-essential businesses closed starting on March 22.

Many essential businesses decided to close too, like this laundromat near the funeral home. "We will reopen once the virus has settled down," its sign reads. But Gov. Andrew Cuomo has said that could take months.

Meanwhile, New York state is running out of ventilators, space, and time. Cuomo said last week that the region may need 140,000 hospital beds in the coming weeks; it currently has about 75,000, including a newly arrived US Navy hospital ship that will help meet the needs of uninfected patients.

Cuomo also said 30,000 ventilators are needed to breathe for patients who cannot; the federal government is sending 4,000. On Tuesday he said the state had ordered more from China but said it was "impossible" to get many more due to a slow federal response — and FEMA's outbidding states. (He said the distribution of ventilators now largely depends on the federal government.)

Doctors and nurses are struggling to keep older and other at-risk patients from succumbing to COVID-19. Healthcare professionals need to defend themselves from infection, too, but they face a shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as air-filtering masks, body gowns, and face shields. Those without recourse are resorting to trash bags, hand-sewn masks, and other improvised gear to prevent from getting sick as long as possible.

Marmo said he's trying to protect his employees and the families who visit his funeral homes. He bought mist-dusters and a barrel of a sanitizing chemical recommended by a professional. He plans to have workers in protective gear regularly spray down facilities to neutralize any possible contamination.

"It's all hands on deck. We're just trying to keep our masks on, our gloves on, and stay sanitized and disinfect everything as much as we can," said Kareem Elmatbagi, the son of Awad Elsayed Elmatbagi — Marmo's business partner next door at Islamic International Funeral Services, which specializes in Muslim clients. "We're just praying to God that we don't catch it."

Elmatbagi said he's especially concerned about his father catching the virus and is trying to keep him at home. "My dad's 65. He's a kidney transplant patient. He's diabetic. He has high blood pressure. He has heart problems. He has a really weak immune system," he said. "He's high-risk."

Exposure to the coronavirus is a tragic and scary complication for the families of patients who die as well: Those who know they've been exposed must quarantine themselves for 14 days, which means they might not be able to attend a funeral at all.

Others are afraid to be around the body or a person who has died of coronavirus for risk of exposure (even though embalming fluids destroy viruses) or just be around anyone else at all.

"It's really heartbreaking right now that people can't honor their dead. It's truly sad," Thomas Cheeseman, a funeral director at International, told Business Insider. "Everybody's on hold right now because they don't know what to do. They're afraid to leave their house, their loved one passed away from it. And now they don't want to be in the room with the loved one because they're misinformed."

During my day at the funeral home, I watched six family members meet to honor an elderly relative. She'd died of the coronavirus and had been embalmed for an open-casket funeral.

Marmo said his staff was concerned about allowing the family to have a typical service, since the city discourages gatherings of 10 or more people. So he limited the number of people who could attend and also asked them to stay at least 6 feet apart (according to guidelines form the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

The family agreed to be photographed but asked their names be withheld and faces blurred. They burned a long stick of incense as part of their tradition. Relatives who were self-quarantined joined the procession via video chat.

Everyone wore face masks and stood far from each other during the rites. It wasn't a tight, warm, and touching service — it seemed awkward and rushed, and staff commented on how disappointed it made them feel that things had come to this.

Even families whose relatives died of other causes, not COVID-19, are affected. International specializes in escorting decedents from foreign nations back home. But the pandemic has made international travel extremely restricted and complex.

One family in particular came to mind for Marmo. "They lost a 7-year-old boy. He came here from Jamaica for special medical treatment," he said. "She [the mother] wants to put her son to rest back home, where he's from, but she can't get a flight out."

![One family in particular came to mind for Marmo. "They lost a 7-year-old boy. He came here from Jamaica for special medical treatment," he said. "She [the mother] wants to put her son to rest back home, where he](https://staticbiassets.in/thumb/msid-74920943,width-700,height-525,imgsize-266238/one-family-in-particular-came-to-mind-for-marmo-they-lost-a-7-year-old-boy-he-came-here-from-jamaica-for-special-medical-treatment-he-said-she-the-mother-wants-to-put-her-son-to-rest-back-home-where-hes-from-but-she-cant-get-a-flight-out-.jpg)

"I told her that I would keep her son with me until this works out," he added.

Collecting payment from people who have lost family members to COVID-19 also comes with complications and risks. Marmo recounted the story of one woman whose husband had died from the disease and was self-quarantining at her home.

"She said she's gonna wear a mask and gloves, I told her I would do the same. She sat on one side of the dining room table. I sat at the other. But I was really uncomfortable," Marmo said. "I was hoping she was writing a check. She gave me cash, and was counting the bills, just touching them all."

Yet another consequence of the pandemic: Workers said the coronavirus outbreak in New York has complicated and slowed the flow of bodies from hospitals to funeral homes and families, and ultimately to a final resting place. "We're stuck right now. We're so new to this, we're in uncharted waters," Marmo said.

Cheeseman said a big factor is COVID-19 testing speed. New York has ramped up processing, but he said it can still take days to get a result, finalize a death certificate, and obtain a permit to cremate or bury a corpse.

Meanwhile, cremations — the most common service — are becoming a logistical nightmare, since crematoriums don't have room to store all the new COVID-19 bodies in an on-site morgue. There are only four crematoriums in the area, Marmo said, adding that they "are overwhelmed" by the new demand.

"We have to confirm with the crematory because they don't want to hold anything in refrigeration. We have a time slot to be there — so they'll go basically from the car right into the retort, which is the cremation oven," one International employee told me. The person asked not to be named to due the sensitive nature of their work.

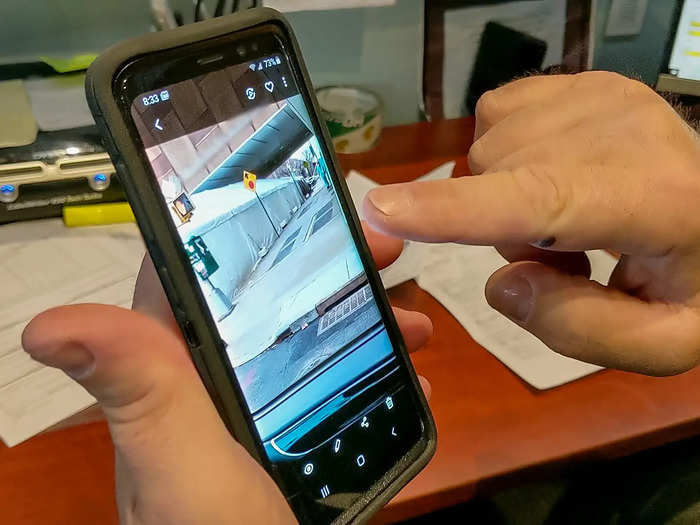

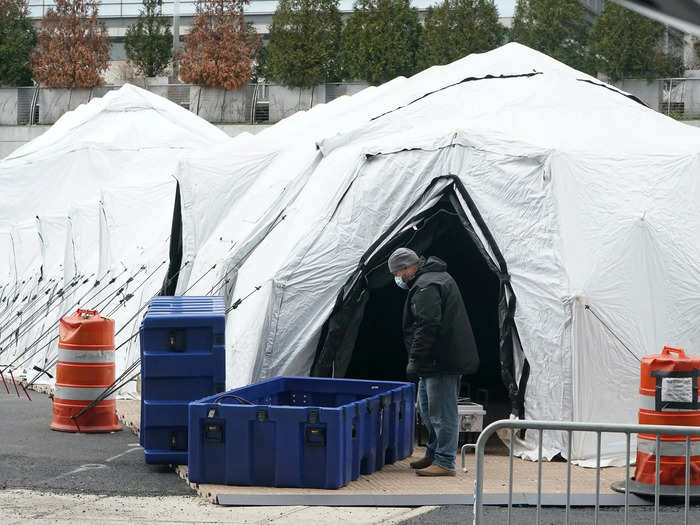

Back at International's office, I learned that two more COVID-19 bodies had been called in to be picked up from the same hospital we'd just left. Cheeseman showed me a few photos on his phone of tent facilities popping up outside of hospitals all over the city — for "containment and testing," he said. "And temporary morgues," a colleague added.

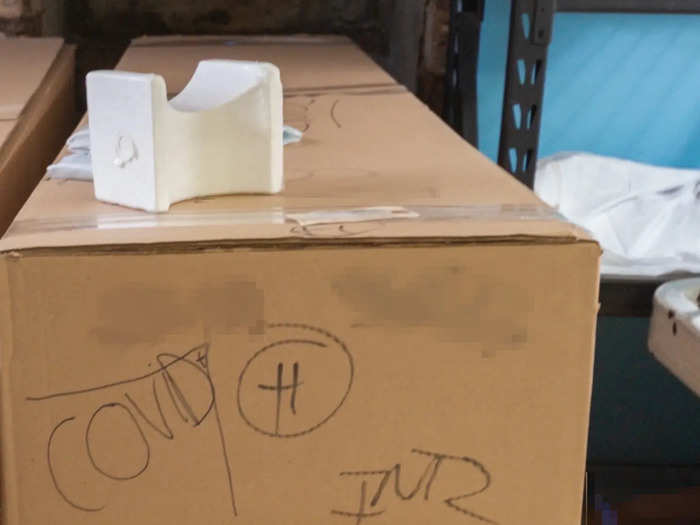

Bodies in various states of preparation waited inside one of International's morgues. Highly evident were boxes of COVID-19 cases awaiting cremation. There didn't seem to be much space left.

New York City's Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) is exploring contracts with vetted funeral homes to help with body removal and other mortuary services. "They only have so many transport vehicles," Marmo said. "So it makes sense for them to make an alliance with funeral directors that have the capability of doing transports."

OCME did not immediately respond to queries from Business Insider about this.

An employee said International typically has a maximum capacity for about 90 bodies at a time. But the industry is having to get creative with finding new space. "We're overwhelmed. Everybody's overwhelmed. All of the funeral directors I've spoken to are overwhelmed," Marmo said. "I never thought I would go through anything like this."

For now, some funeral homes have resorted to unused chapel and other spaces for storing boxed bodies that are imminently headed to a crematorium.

Marmo said it would help if the local or state government set up temporary refrigerated morgue facilities around the city to support private funeral home overflow — perhaps chilled tents or semi-trailers. "It's still cool out. If this extends to May or June, how are we going to do this?" Marmo said.

Marmo added: "I've thought about putting a refrigerated trailer outside the funeral home. But that's horrendous."

Marmo said that if more refrigeration space doesn't come when cases really begin to spike in April and May, a state order to send bodies straight to a crematorium or grave site instead could help people like him handle the volume with integrity. But families would then have to sacrifice funeral services.

Marmo is frustrated by and worried about the situation. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, he said, families could at least get together to honor their loved ones, especially those who'd served. "There's no way they're going to have full police funerals now. There's no way," he said. "After 9/11, at least they were giving people funerals they deserved."

Marmo said people sometimes tastelessly joke that his business must be great due to the pandemic, but he strongly disputes that notion.

"It's kind of balancing out because overtime is gonna be crazy," he said of his employees working around the clock. "These guys out there and girls? They're breaking their asses."

After finishing my visit, I wiped down just about every nook and cranny with sanitizing wipes. I also did a complete change out of my clothes before leaving.

I took a decontaminating shower when I got home, then collapsed from emotional exhaustion. Funeral directors are used to dealing with death, but I was not. And it was abundantly clear to me that much more if it is yet to come.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement