- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- An architect who built his dream tiny home in Colorado shares 30 photos that go behind the scenes of designing a tiny house

An architect who built his dream tiny home in Colorado shares 30 photos that go behind the scenes of designing a tiny house

Greg Parham owns Rocky Mountain Tiny Houses, which designs and builds tiny houses in Durango, Colorado. It also offers consulting services and sells tiny house shell builds, DIY kits, and plans for tiny house DIY-ers.

Non-DIYers will pay Rocky Mountain Tiny Houses anywhere from $30,000 to $150,000 for finished houses, according to Parham. He said the average cost for a tiny house, from design to construction to completion, is $68,000.

Tiny house projects vary, but after establishing logistics with customers — cost, timeline, contract, down payment, etc. — Parham begins the design process.

The design stage is a "somewhat linear yet organic process of starting with macro-concepts and breaking them down into micro-parts," Parham said. "In the end, it's all about the details, but you have to stay focused on one at a time or you will get overwhelmed."

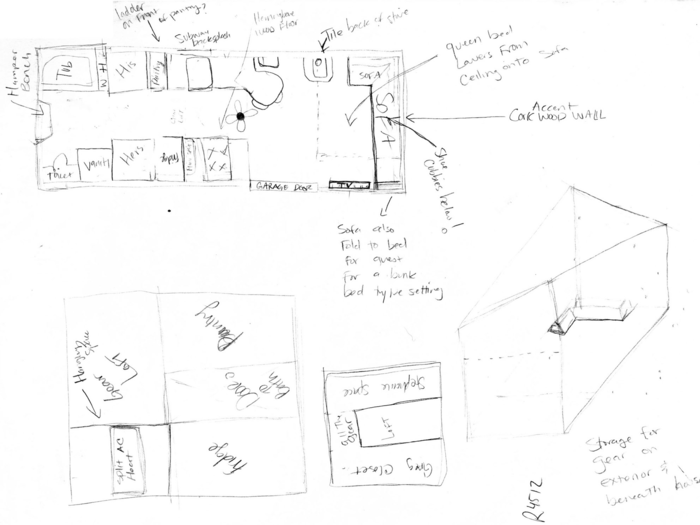

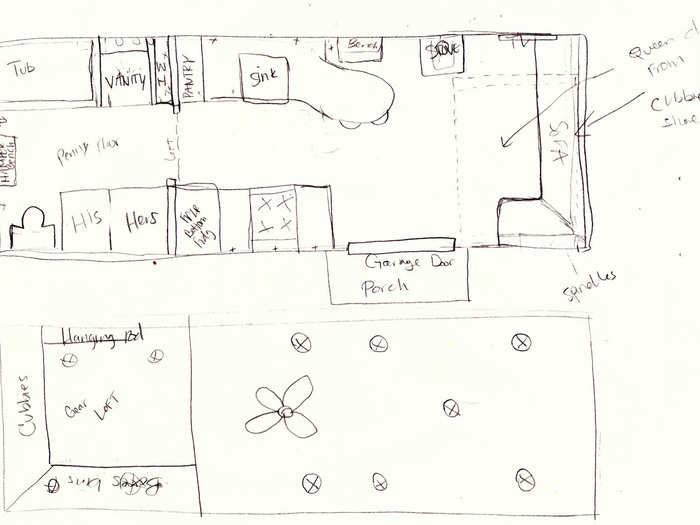

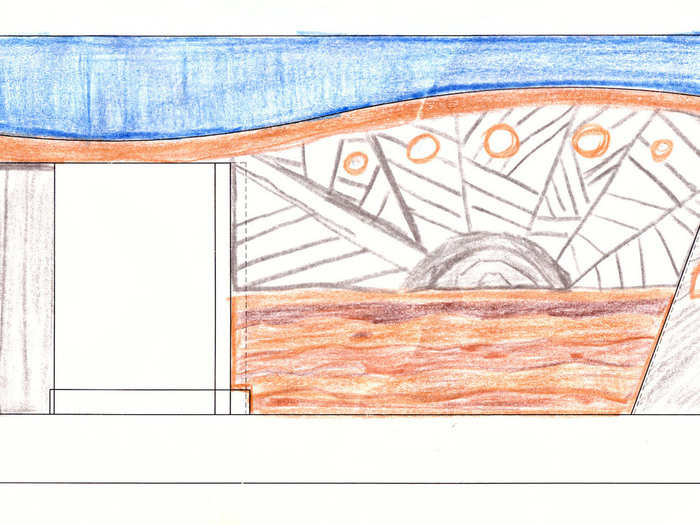

"Things usually start off 'rough' or very unrefined," Parham said. "The first attempts are normally about capturing the big-ticket ideas, or the absolute 'must' the design must have."

Sometimes customers provide Parham with hand-drawn sketches, links to tiny house builds they like with written descriptions of changes they want made, or detailed 2D- or 3D-computer generated plans.

"We ask customers to provide written descriptions of design details they want incorporated, as well as a Pinterest page with ideas and knick-knacks if these images will better explain the aesthetic or functional goal they are trying to attain," Parham said.

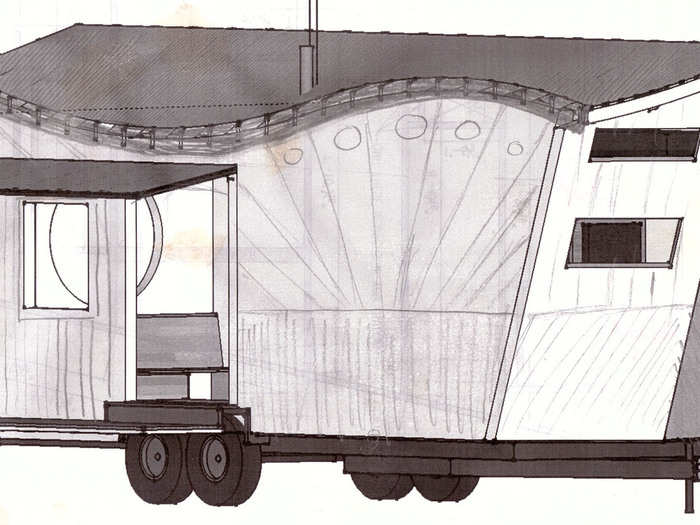

Most people have a general idea of what they are looking for in regards to trailer length, roof and house shape, interior and exterior design style, and fixtures, Parham said.

But customers don't always realize that certain things need to be taken into consideration, he continued, adding that there are hundreds of intricacies that it would take him days to explain.

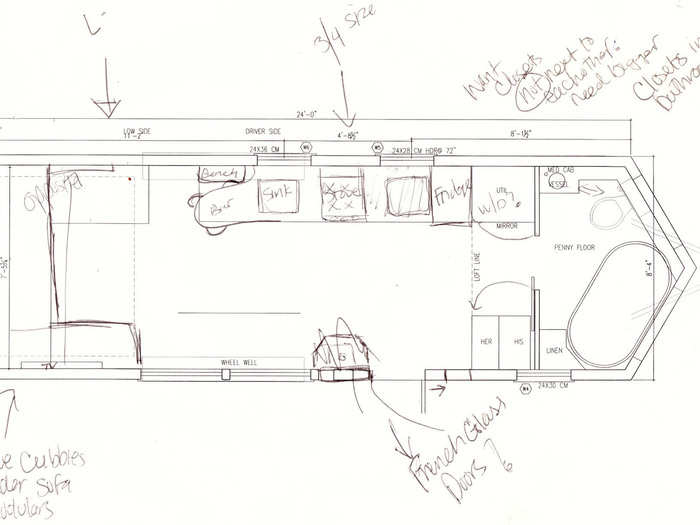

The most common mistake customers make in their sketches is not accounting for wall thickness. "They think they have an extra eight to 12 inches in width to work with," he said. "Walls are at least four inches thick, not the width of a pencil line in a sketch, so please plan accordingly for this."

"We also see things like people placing bathrooms or other plumbing on the rear of the trailer," he said. "This is generally a bad idea since the pipes that go under the trailer often get damaged in transport when the trailer goes through dips in the road and this portion of the trailer is most vulnerable to coming in contact with the road."

There are other inherent problems to building on a mobile foundation. "Things like French Doors are beautiful and totally doable, but just know they will settle and require some tuning every now and then," he said.

"If you move a lot, glass pendants are a terrible idea!" he added. "If you live in a really cold climate, multiple forms of heat is a must, and we will also probably beef up the insulation and the water heater to handle the extra cold."

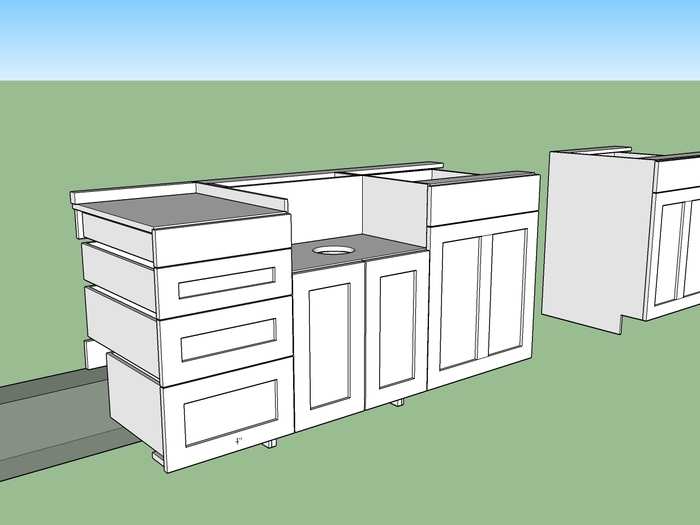

Parham then takes all this information and begins designing it with Autocad or Sketchup software programs.

"Oftentimes I will use CAD to scale things out very quickly and draw the floor plan, and then export into Sketchup, where we start extruding walls up and adding built-ins," he said.

They usually go through two to five versions before settling on a final plan, which can take a few days or weeks.

"Things very rarely scale out the way people think, so when we show them the realities of how much space things take up, where the wheel wells fall, weight balance issues, etc. they often adjust their vision," Parham said.

"Once it comes time to actually build that component, we will start a new drawing with the extents of that massing block, and then start to detail it out," Parham said.

"Some components are large and complex, so we even have to start smaller files focusing on a portion of that component until it is easily comprehended in its elemental form," he added.

Whereas the design and contract process can take anywhere from a few days to a few months, the builds take three to 10 weeks, depending on the simplicity. On average, it's about seven weeks per build, Parham said.

When budget is a concern, time is a concern, he added. This makes one-off pieces a bit more time-consuming, so they strive to do everything they can to achieve design goals while balancing the budget.

They begin construction with a blueprint, but several micro-details — like the electrical plan, plumbing propane, HVAC, flooring, finishes, drawer pulls, etc. — "are made on the fly as the house materialized into built form," Parham said.

"A lot of times we have to create mockups or material palettes for the customer to see since they can't visit our shop," Greg said. "During the build, constant contact is critical. It's not uncommon for us to exchange up to 10 calls or emails per day to confirm a lot of these micro-decisions."

Parham said the design process evolves during the building process because some things being built don't go together as anticipated, or his team realizes it could be modified to make construction easier or stronger, or to make the design more functional.

"It is not uncommon to change things on the fly and then take the blueprints and hand draw over them with revisions," Parham said. "The drafting software helps paint a useful picture, but never paints a perfect picture like photos and visits to our shop do."

"Because we are a highly custom builder working on 'untested' designs, small conflicts are inevitable, such as the toilet lining up over a structural steel member in the trailer chassis, or the laundry box falling over the wheel well," Parham said.

To make changes to accommodate these issues, they offer suggestions to customers on how to remedy the problem all while keeping their goals and design sensibility in mind.

"The more houses we build, the less of these issues we encounter, but there will always be some issues that pop up, especially when a customer wants us to install something that has unclear or unusual installation requirements that we just could not have planned for without having the fixture or manual in our hands," Parham said.

Parham says they have cool customers who desire unique designs. "There are several trailer lengths to choose from, several roof shapes, endless material possibilities, and endless possibilities for creative solutions to functional needs, such as a piece of furniture that can function as a table, a desk, and a bed," he said.

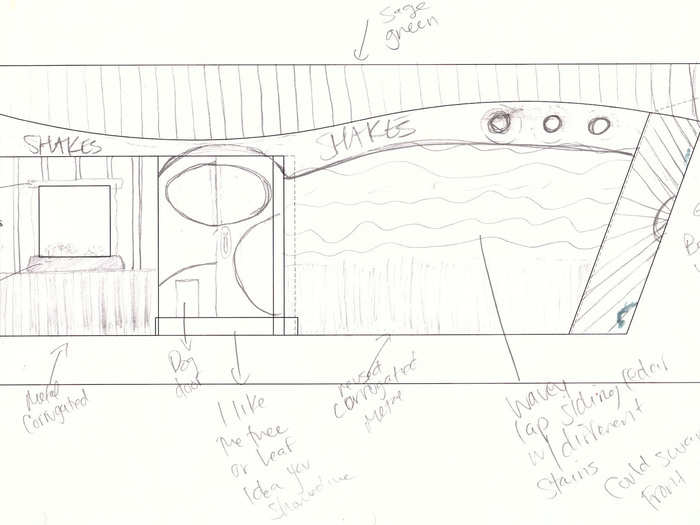

It took Parham about four days to complete the sunray barn wood siding and two days to complete the ombre shakes on the back wall of the exterior of his tiny house.

The result is a fully customized tiny house "built from scratch."

Source: Rocky Mountain Tiny Houses

Parham made his own tiny house "extra special" for trade shows. While he has a knack for macro-decisions, like roof shape and overall floor plan, his wife, Stephanie, has an eye for micro-details.

Stephanie is a Francophile and fan of older European architecture, which carried over into door shapes, hardware and fixtures, and the herringbone floor pattern in the entry, Parham said.

Parham likes clear coated and stained wood, while Stephanie prefers painted surfaces and a few accent colors. The final composition is a compromise of the two styles.

"Several of the details were very difficult and time-consuming, but totally worth it in the end," Parham said. Framing and finishing the curved roof was time-consuming and tedious, he said —but it's his favorite design aspect.

It also took a lot of hours to craft the entry doors, and two days to set and epoxy the penny floor in the bathroom.

It took them almost a full day to lay the small herringbone floor section. And as for the kitchen, it took at least a week to mill, glue up, fill cracks with turquoise and epoxy, and coat the mesquite counters.

Some details, like the dovetailed drawers and glued-up shelves and door faces, carried over from other parts of the house, Parham said.

"For instance, the elevator bed structure needed to be very sturdy yet attractive, so we started with using strong hardwoods, walnut and alder," he said. "I chose to use a special type of handcut dovetail that once assembled, would give the joint a tremendous amount of strength and stability without using any fasteners, while giving visual appeal at the same time."

He added: "Since I used dovetails here, this also inspired me to use exposed dovetails on our closet drawers, and dovetails just look even cooler with contrasting wood colors, and then this inspired me to play around gluing up different wood colors on the closet doors, and this all tied into the dovetails on the bed frame."

"It took an insane amount of man-hours to craft this house, but we didn't have to pay for that labor, which is another reason we went a little out of the ordinary," he said. "Crafting something of this nature takes a lot of skill in addition to the time, and you can't expect Champagne quality on a beer budget, but most people do."

Because they take this house to shows, people see what Parham is capable of, but "when I give them a price on how much something like this would cost, they lose interest quickly."

For Parham, the effort was ultimately worth it. "I notice and appreciate all the little details every single day!" Parham said.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement