- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- A photographer spent years exploring India's apocalyptic 'capital of coal' and returned with unreal photos

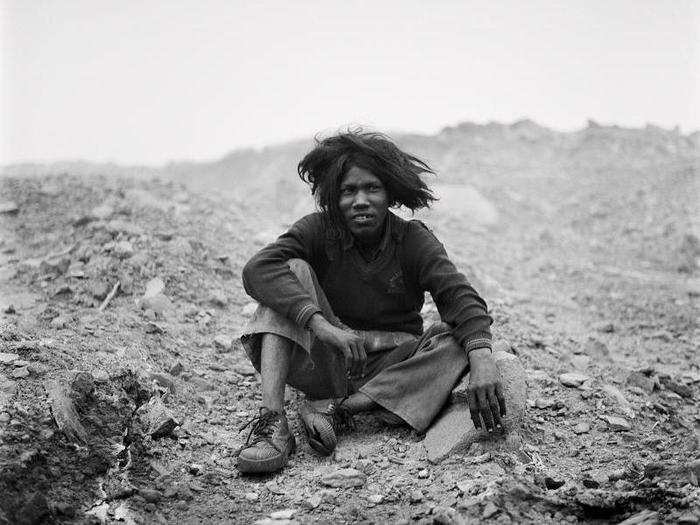

A photographer spent years exploring India's apocalyptic 'capital of coal' and returned with unreal photos

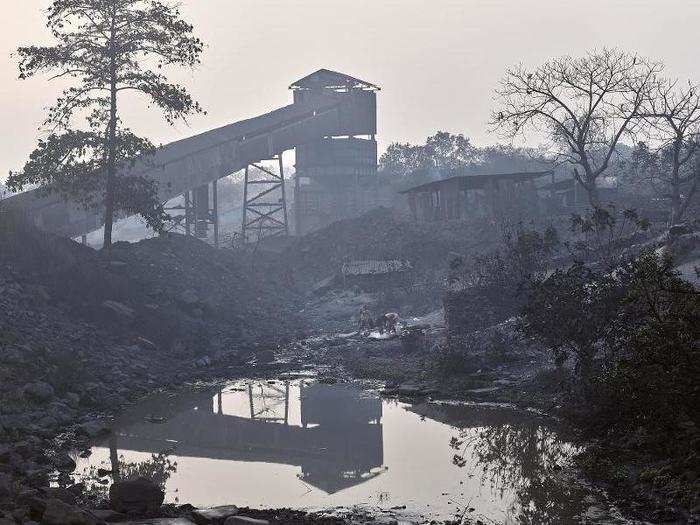

Over 65% of India's power comes from locally mined coal. The Jharia fields are the country's biggest reserve, with approximately 11 billion tons of coal.

Most of the mining done at Jharia is in open pits or strip mines, because it is faster and more profitable. But doing so exposes coal to oxygen and is highly destructive to the environment.

Source: Al Jazeera

Coal fires have been burning in Jharia for over 100 years. Large-scale open pit mining was ramped up in the 1970s when coal companies were nationalized by the government. It has made the fires far worse.

Source: Al Jazeera

Sardi first visited the Jharia mines in 2011 and was shocked by the living conditions.

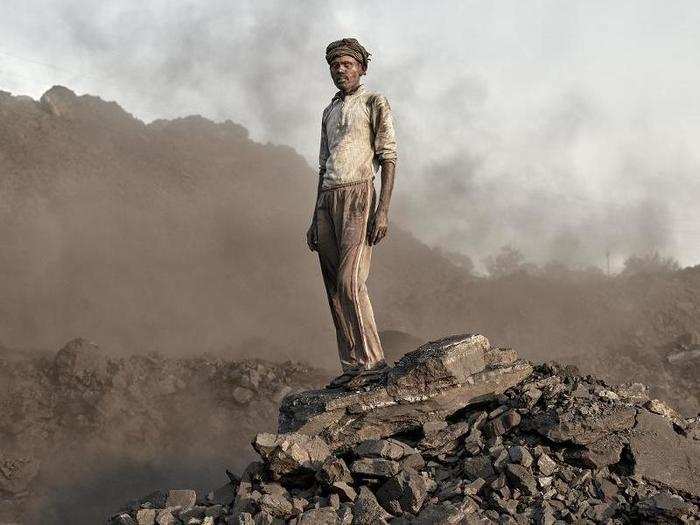

"The environment is terrible," Sardi said. "As soon as I came close to it, I started coughing. All this dust gets into your system. It sticks to you. I could feel it for weeks after."

Coal is everyone's livelihood in the area. While most of it is mined by the state coal company, many locals illegally mine it themselves.

Source: YourStory

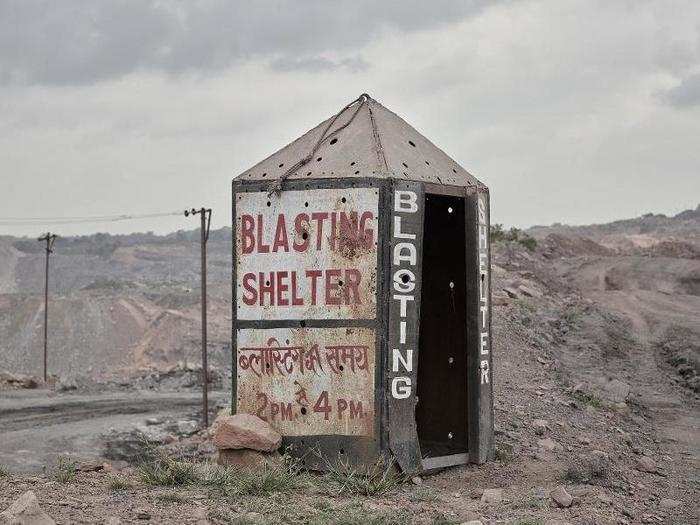

The area is so filled with coal that locals can simply dig a hole in the ground or blast rock with gunpowder or dynamite.

Source: YourStory

Much of the coal in the areas around the Jharia mines is coking coal, also known as metallurgical coal. It is a key ingredient in steel production, which it makes it very valuable to India's development. It is also highly flammable.

Source: Al Jazeera

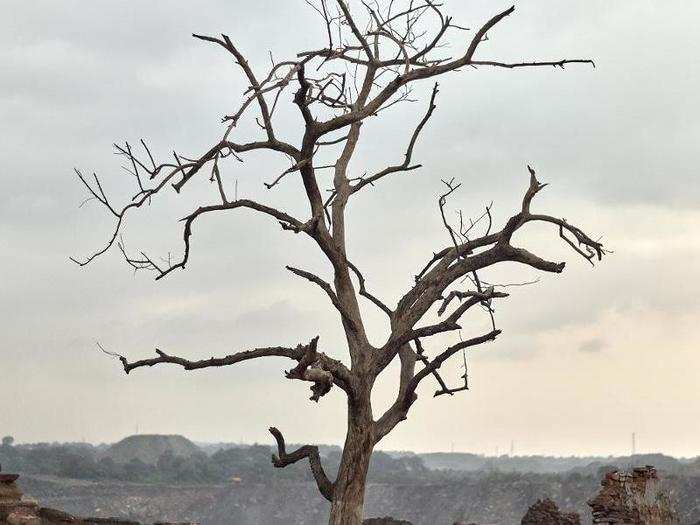

As the mining operations have expanded, they have moved closer and closer to the villages. In many cases, the mining has caused the ground beneath houses to collapse.

Source: Caravan Magazine

All over Jharia, there are fiery cracks and pits that spew clouds of toxic gases like sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, and mercury.

Source: New York Times

With no heating in their homes and sometimes cold winters, locals often gather around the coal fires for warmth, Sardi said. It is very dangerous to inhale the fumes, but locals have little choice.

While the Indian government has created a master plan to deal with the fires and the environment, local press reports suggest little has yet been done.

Source: Caravan Magazine

A physician at a local hospital told Al Jazeera that 99% of people in the area are affected by the fumes and the fires, saying that there are widespread cases of tuberculosis, wheezing, asbestosis, pneumoconiosis, and skin allergies.

Source: Al Jazeera

Compared to mining sites around the world, locals and workers' quality of life is terrible, according to Sardi.

"Miners in Russia at least have a chair to sit on and a cup to drink their coffee out of. These people have nothing. They have a shirt, a pair of shorts, and flip-flops. That's it," Sardi said.

Some of the planned resettlement schemes call for moving up to 700,000 people to newly constructed housing away from the mines. But, recent reports suggest only a tiny fraction have actually been moved so far.

Source: Al Jazeera, Caravan Magazine

After locals have been evacuated, the villages where they once lived are often opened up into mines. Coal is everywhere.

Many locals told Sardi that they are convinced the government won't put out the rampant coal fires because it gives them an excuse to relocate the locals and access the coal underneath.

The government and the coal company have denied this, noting that coal fires are "notoriously difficult to kill" and extremely costly. Billions of dollars' worth of coal have been burned by the fires.

Source: YourStory

The villagers aren't entirely wrong. Indian prime minister Narendra Modi has said he wants resettlement efforts accelerated both so the fires can be more effectively extinguished and to open up more access to coal.

Source: Al Jazeera

Sardi said that the situation has changed dramatically as he has visited again and again over the last eight years. When he first started visiting, locals were very reluctant to move because their entire community was in their village and there were few public services available in the resettlement areas.

But as the resettlement areas have become more populated, markets, schools, and medical clinics have sprung up, Sardi said, making it more appealing to move.

But locals don't just fear the loss of their communities or homes when they resettle. Most rely on coal to make a living. Many fear that moving to the resettlement zones, some of which are more than 10 miles away, will mean needing to find a new job.

Source: YourStory

Some activists have demanded that resettled villagers be provided government jobs. But considering the sluggish nature of the resettlement, it seems unlikely. For now, one thing is certain: The coal fires will keep burning and the mining will continue.

Source: YourStory

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement