- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- A music exec who lived through the industry's darkest period reveals what to do when a technological tsunami is about to crush your business

A music exec who lived through the industry's darkest period reveals what to do when a technological tsunami is about to crush your business

1. Remember, it may take time to grasp the nature of the threat

2. Accept that the competitive threat may evolve, morph and quickly adapt

Napster was a centralized peer-to-peer service. A central server indexed the users and their libraries of MP3 song files so others could access them. The music industry had seen earlier, clunkier, and far less popular versions, called File Transfer Protocol technology.

"We started with FTP sites," Sherman said. "Napster was the next form of piracy in 1999 and then a couple of years later came a decentralized form of piracy. Then, came cyber lockers and so on… each generation of formed piracy had a completely different scale beyond anything we had seen before. And so we saw very quickly that things were spinning out of control."

3. Expect your entry barriers and moats to be breached

The year before Fanning invented Napster, the big recording companies thought they had piracy-proofed their business thanks in large part to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which outlawed the cracking of anti-piracy protections on CDs and the distribution of pirated songs by Internet services.

But the new breed of services let users store music files on their computers, rather than on centralized servers owned by internet providers. That meant that internet service providers weren't liable for the pirated music and it left the record labels with no effective way to stop the problem.

The DMCA, the record industry's main bastion of defense against piracy, was "obsolete within eight months," says Sherman.

4. Know and believe in your product

Not only is Sherman (pictured above) a Harvard educated attorney, he also plays the piano and is an amateur lyricist. Music is part of his life.

He joined the RIAA as general counsel in 1997 and he helped industry leaders obtain exclusive rights over digital performances of their songs. This is the right that requires on-demand streaming services, such as Spotify, Apple Music and Amazon, to negotiate licenses before distributing music.

That Sherman's hiring coincided with the rise of file-sharing was likely a blessing and a curse. He noted that there were few people in media that had faced a technological threat like P2P sharing technology. Certainly, no one else in the music sector.

Sherman would learn as he went, and eventually become expert in tech disruption, though he would probably have preferred not to.

5. Beating back a threat is not enough. Building a lasting market for your product should be the No.1 goal.

For all the pain that piracy was inflicting on the music business, defeating the pirates was not the real objective, Sherman says.

The most important thing was creating a blueprint for the music industry to operate in the digital age. Having a vision for the business from the beginning, no matter how many times it has to be revised, is vital to keeping the focus on what's most important: providing the best product and customer experience.

In today's world of subscription music services, it's easy to forget that 15-years ago, during a time of great upheaval for the record business, the top labels had largely lost control of their distribution. Among young music fans, paying for songs was nearly a subversive concept.

"We were always looking at the big picture rather than getting completely lost in the specifics of a particular form of piracy or a particular kind of digital delivery system that was legitimate," Sherman says. "We were always trying to figure out how do we gain some sort of security over the marketplace, create a legitimate marketplace, and fight piracy and not one without the other."

6. Recognize who your true friends are and who your enemies are

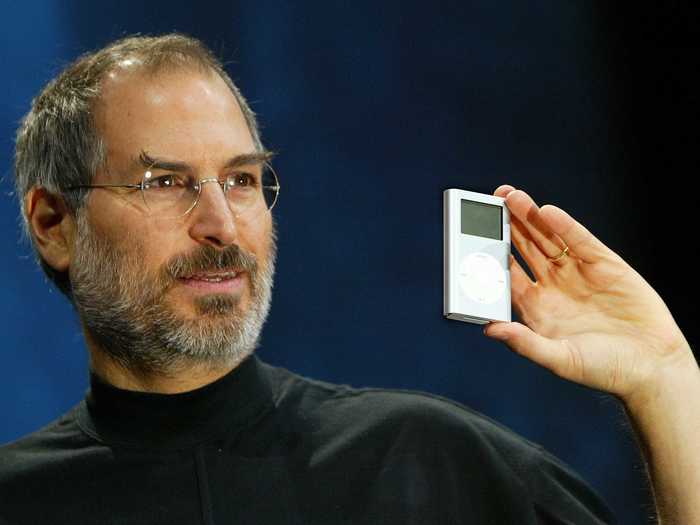

On October 23, 2001, Apple released the first version of the iPod, which allowed consumers to store thousands of songs on a digital music player not much bigger than a cigarette lighter.

For the music labels, the device arrived at exactly the wrong time; just as the file-sharing craze was going mainstream.

Some artists, such as Bon Jovi and members of Pink Floyd claimed that Steve Jobs, the Apple CEO and cofounder, had devalued music and killed the record business. Some of the record label leaders didn't like the idea of allowing CD owners to rip songs, and wanted to wage legal battle to stop it.

But others recognized the potential for a new business model, especially after Apple introduced the iTunes online music store that let consumers download any song they wanted for 99 cents.

"I think most people (in the music industry) would regard iTunes as a friend," Sherman said. "Because Steve Jobs, unlike most of the tech companies at the time, was trying to offer music legally."

7. Choose your battles carefully

Sherman now says that some of the label honchos at the time believed that under copyright they could argue that consumers who owned CDs lacked the right to rip songs from the discs and onto their iPods.

"There’s law that would be consistent with that," Sherman says.

But fighting that battle would have been a mistake, and could have jeopardized the bigger picture.

"I remember having some difficult conversations with some of the heads of the companies because they were getting some advice inside that this was not a good approach," Sherman recollects.

8. Don't be intimidated by Google, Amazon or any larger rival.

Sherman very early tried to pull together all the stakeholders in digital music, such as online stores, record labels, music publishers, subscription services, software and hardware makers into consortiums.

He hoped that deals could get done that pulled them together and enabled all to profit. The consortiums didn't last long but the relationships built there helped in the long run.

Sherman reached out even to tech companies that the music industry considered hostile. This meant paying a visit to the Googleplex.

YouTube, which Google acquired for $1.6 billion in 2006 had emerged as a music titan. Millions around the world visited the site to watch music videos from all the world's major acts, such as Rihanna, Shakira, Celine Dion, and Psy.

9. Collaboration isn't always easy but it's vital

But when the RIAA paid a visit to Google's headquarters in Mountain View, Calif. the relationship between the music sector and the company was tense.

Under copyright law, the record labels were required to send YouTube a "takedown notice" when they wanted unauthorized music removed from the site.

When we went to Google that day, they said 'Why don't you do a Google townhall?' They apparently put these together on the spot. It wasn’t planned. We said, 'Sure.'"

"I remember when I got up to speak," Sherman continued, "I told them what our experience was like as an organization that was attempting to protect the rights of music creators and that for some reason the most advanced tech company in the world—Google—was not allowing us to submit our takedown notices by email. They were requiring us to fax them. I thought that the story would make everybody hang their heads in shame. Instead the entire audience, about 400 or 500 people, broke out in spontaneous applause because they were so proud that their company was making it impossible for us to effectively enforce our rights."

10. Don't waste time on self doubt

That kind of reception from Google workers was uncomfortable and it had to be a little humiliating, but Sherman said he didn't waste time taking criticism personally.

At the beginning of the MP3 piracy phenomenon, Sherman says he beat himself for not being able to "fix" the problem. But eventually he realized, the problem reflected a bigger issue that could not be solved by any one person or group.

"This was a cultural phenomena where the engineers in Silicon Valley really were anti-copyright. And even though they loved music, they couldn’t see a connection between what they were doing and the hardship that creators were beginning to face. It illustrated that this was a multidimensional and multi-factor issue that would require years to correct as well as a lot of innovation in business models and a lot of education," Sherman says.

11. Don't stop trying to find common ground with adversaries

Over the years, Google's relationship with the music sector improved. YouTube has done a better job of taking down infringing music and links to pirated songs are harder to find on Google's search than before, Sherman says (though he says it still has a long way to go).

One of the factors that may have contributed to the thaw between them is YouTube's hiring of former Warner Music Group exec Lyor Cohen. Cohen has nearly unparalleled street cred both with artists and music leaders.

"I think Lyor Cohen is doing a very good job of persuading the people at YouTube that they need to be partners with the music industry," Sherman said. "It’s still a difficult relationship but they have been much more sensitive to the need to work with artists, labels, publishers, songwriters in terms of creating a service that works for creators as well as themselves."

12. Alliances may not pay off quickly, but be patient

The RIAA worked hard to build international consensus with other copyright interests as well as governments across the globe. Sherman did his part by flying to France to do his share of lobbying, meeting with French government officials in October.

Some of those paid off last week.

Music artists in Europe have long complained that their financial relationship with YouTube was too one sided in favor of the video service. They lobbied for new copyright laws. The European Union listened and last week the EU approved directives designed to force YouTube, and similar sites that operate in Europe to pay more to content owners than in the past.

This is a big victory for the music sector because the hope is that the EU decision will lead to similar laws elsewhere around the world.

13. Place some bets. You'll often get it wrong but it's important to try

After 20 years at the RIAA, Sherman has announced his retirement effective Dec. 31.

He's certainly leaving the industry in better condition than he found it.

In addition to the legislative victory in Europe, people are paying for music again. The popularity of Spotify, Apple Music and other subscription streaming services has led to revenue growth for the sector.

Sherman can take credit for some of this as he was the one who helped the music industry obtain exclusive rights for digital transmissions.

"That right didn’t exist before 1995 and 1998 when we got Congress to give it to us," Sherman said. "We have exclusive rights where we get to negotiate with Apple and Spotify and Google Play for the (on demand music they provide their users). They are the bulk of our revenues today and are responsible for all the growth and recent success. Getting that legislation passed when there were digital music services that opposed it, it was critical lesson that you have to be ahead of the curve."

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement