- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- A floating plastic island in the San Francisco Bay may offer a new way to protect coasts from floods. It could even house people inside.

A floating plastic island in the San Francisco Bay may offer a new way to protect coasts from floods. It could even house people inside.

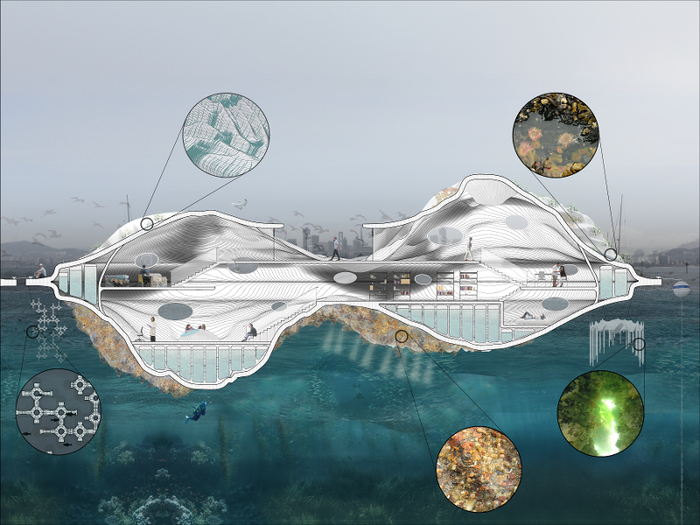

The island launched in the San Francisco Bay in August. It's roughly the size of car and made of fiberglass, a type of reinforced plastic.

Fiberglass doesn't corrode or rot, so it should be capable of withstanding the harsh marine environment.

A Bay Area fabrication company named Kreysler & Associates helped build the structure, using robots to carve the mold. Workers then covered the surface with fiberglass by hand.

The team hopes that animals will attach themselves to the island, creating a mini ecosystem.

"Animals love attaching themselves to hard surfaces," Marcus said.

The process in which marine creatures latch onto boats is known as "fouling," and it's often viewed negatively by sailors, since it can damage boats or cause them to slow down. But Marcus' team thinks fouling could be used to humans' benefit: If enough animals attach to a floating structure, he said, they might reduce the force of waves against the shore.

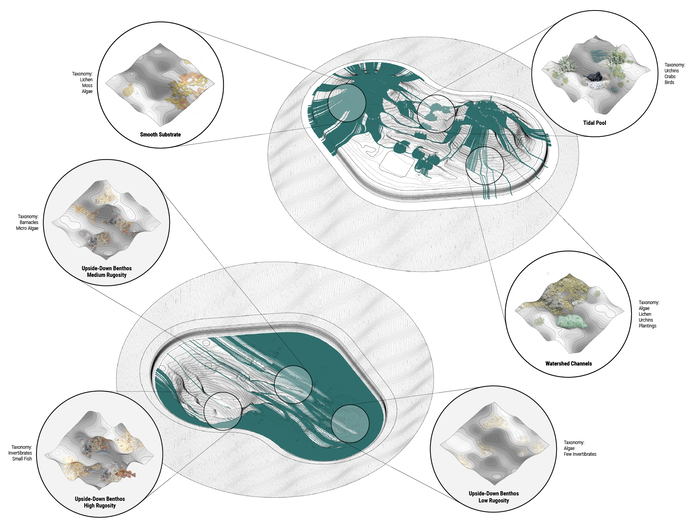

The structure is lopsided to foster marine life.

The structure consists of two mounds with a valley in the middle. Its texture is bumpy to give the island more surface area.

"Different scales of peaks and valleys can allow different sizes of animals to attach," Marcus said.

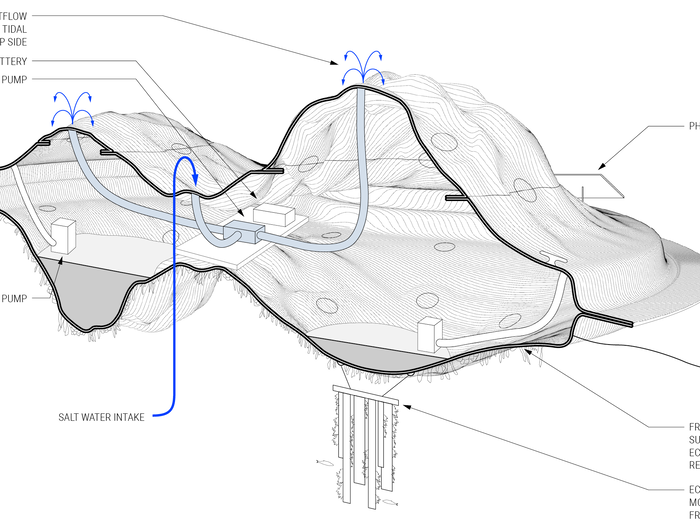

Inside the structure, an irrigation system brings in salt water and pumps it onto the surface of the island, creating a wetland. Exterior solar panels help power the flow of water.

Caves underneath the structure create "fish condos."

The caves offer a hiding place for smaller fish to escape predators. They also attract plankton and other nutrients that support the bottom of the food chain.

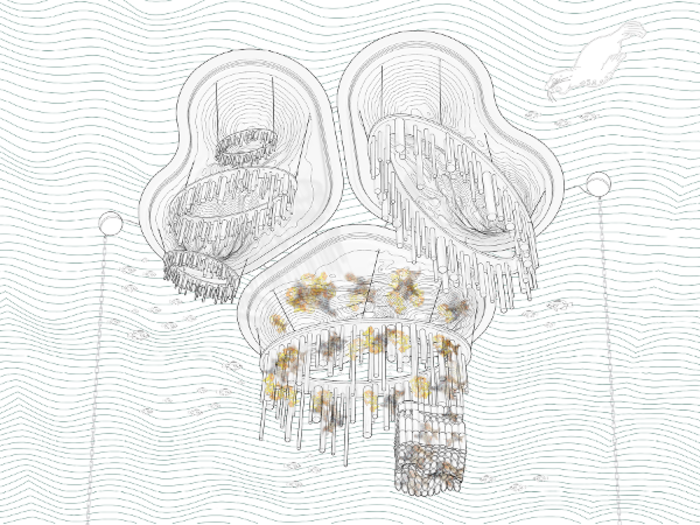

The team will soon install an "underwater chandelier" for animals to latch onto as well.

Hanging columns beneath the island could create a natural habitat for invertebrates like seaweed, barnacles, and oysters. From there, the Float Lab team hopes the structure will attract larger animals like fish.

Each month, marine ecologists will dive below the island to examine how animals are interacting with the columns.

Marcus said one of the columns might feature a 3D printed version of calcium carbonate — a mineral that helps marine animals build skeletons and outer shells.

When carbon dioxide gets absorbed by oceans, it dissolves into carbonic acid. This causes the water to become more acidic, which decreases the amount of calcium carbonate available to animals. If marine animals can't build effective skeletons and shells, it could disrupt entire ecosystems.

By slowing down waves, the Float Lab could mitigate the impacts of tsunamis or hurricanes.

The CCA team thinks structures like this island could protect coastal homes from flooding by acting as giant fortresses that buffer against strong ocean waves. Oyster reefs do this naturally, but they can't be placed in strategic offshore locations. The team envisions building an entire fleet of Float Labs that attenuate flooding.

"Let's say you had a network of a hundred of them tiled together," Marcus said. "That could be a potential tool to help protect vulnerable shorelines."

In the US, coastal erosion already causes around $500 million worth of property loss each year.

The Float Lab team uses computer simulations to make predictions about how an entire fleet of these islands could operate.

A single Float Lab wouldn't do much to block waves, Marcus said, but computer models allow his team to scale the impact of their design. Eventually, the models could tell them how many Float Labs they'd need to place in the water to see effects.

"Now that the Float Lab is deployed, we'll have a better sense of how it works because it's anchored in one place," Marcus said.

The design could one day incorporate human habitats.

Floating city concepts have been touted as a way for people to escape rising sea levels. But the current Float Lab design isn't ready to by occupied by people.

"A human can get inside of it — I've been inside of it — but I wouldn't say it's designed for human occupation right now," Marcus said. "We're trying to think from the opposite end of the spectrum — designing from the substrate and then animals up."

In the future, Marcus said, marine animals could live on the outside of the structure, while humans could live on the inside.

For now, the inside just contains irrigation pumps.

Technically, floating cities are illegal in the San Francisco Bay, but the city has been supportive of the team's research.

"It's illegal to place any cover over the bay, whether that be sediment or dredge or floating structures," Marcus said.

His team secured a permit to operate and observe the Float Lab for three years in waters owned by the Port of Oakland. The port helped supervise the launch and worked with the designers to find a safe place for the island. Marcus said there's a chance the Float Lab could get its permit renewed, but for now, the research timeline is capped at three years.

The Float Lab is different from other floating architecture concepts because it's about testing materials — not housing communities.

Floating homes are real, but floating cities still only exist in theory.

In 2008, political theorist Patri Friedman teamed up with PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel to form the Seasteading Institute, a libertarian think tank that advocates for the construction of floating cities. The group sees floating cities as part of a utopian vision to develop societies without taxes or government regulation, but they've struggled to make the concept a reality.

Marcus said his team has connected with the Seasteading Institute a few times.

"They've come into CCA where we teach. They're familiar with our work," he said.

But the Float Lab project, he added, has little to do with creating a new form of urbanism.

"We just have very different motivations," he said. "Our project is definitely focused much more on the small scale."

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement