- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- 75 years ago, US troops threw the Japanese off North American soil in a frigid, 'forgotten' World War II battle

75 years ago, US troops threw the Japanese off North American soil in a frigid, 'forgotten' World War II battle

Japan's Northern Area Fleet, which included two small aircraft carriers, left the Kuril Islands for the Aleutians in May. The Aleutians are swept by cold winds and frequently shrouded in dense fog. Many of the islands have craggy mountains and scant vegetation.

The US knew of the Japanese plans by May 21. Adm. Chester Nimitz, commander of the US Pacific Fleet, kept his carriers for Midway but sent one-third of his surface fleet to the Aleutians. The first days of June 1942 saw scattered contact between US and Japanese forces, including a Japanese raid on Dutch Harbor that did little damage.

Source: US Army

The Japanese launched another raid on Dutch Harbor the following day, killing 43 US personnel and destroying 11 US planes at the expense of 10 Japanese planes. US planes located the Japanese fleet but couldn't attack. Nimitz's surface ships did not engage during this period.

Source: US Army

After Yamatomo's devastating loss of four carriers at Midway, he ordered the Northern Area Fleet to proceed with its mission to compensate for his failure. The island of Kiska was occupied on June 6, and the next day Japanese forces took Attu, the westernmost island in the Aleutians. No opposition was encountered on either island.

Charles Foster Jones, Attu's radio operator, died during the invasion, and his wife, Etta, the schoolteacher on the island, was captured. Attu's Aleut residents were taken to Japan for the rest of the war, becoming the only North American community imprisoned there during the war. Sixteen of the 40 prisoners died of disease and starvation in captivity.

Japan dispatched more aircraft carriers to the Aleutians in hopes of destroying more US ships. Nimitz had ordered his forces north to attack the Aleutians on June 8, but he changed that order, likely out of concern about Japanese naval reinforcements and land-based planes. The Aleutians weren't worth much without Midway, but they did allow the Japanese to check a US attack on Japan from the north.

The US started planning to retake the two occupied islands, and bombing raids continued on each throughout the summer, which convinced the Japanese of US plans to attack. They increased their garrisons to 1,000 men on Attu and 4,000 on Kiska.

Source: US Army

The bulk of US resources were focused elsewhere in the Pacific, but preparations for the Aleutian campaign continued during the latter half of 1942. By January 1943, the Alaskan Command had 94,000 troops. After an unopposed landing on Amchitka Island on January 11, US forces were within 50 miles of Kiska. Despite harsh winter weather and Japanese attacks, US personnel had built an airfield there by mid-February.

The US also imposed a blockade on Attu and Kiska in mid-March. A Japanese supply force attempted to run the blockade on March 26, 1943. The resulting clash was the last and longest daylight surface naval battle of fleet warfare. The smaller US force turned the Japanese force back, and from then on the garrisons on Attu and Kiska went without resupply, save for the small shipments brought in by submarine.

On April 1, US Navy Rear Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid, the commander of the Northern Pacific Fleet, got permission to invade Attu in what was called Operation Sandcrab.

The US Army's 7th Infantry Division, then stationed in California, was picked to lead the operation. The division trained for amphibious operations throughout April, but the cold, wet Alaskan weather was in stark contrast to the warmth of California, and the unit did not have sufficient cold-weather gear.

During the battle, some frigid US soldiers wore superior cold-weather clothing taken from dead Japanese troops, risking being confused for the enemy.

A bombing campaign began in early April, but it was largely focused on Kiska, as Attu was shrouded in fog.

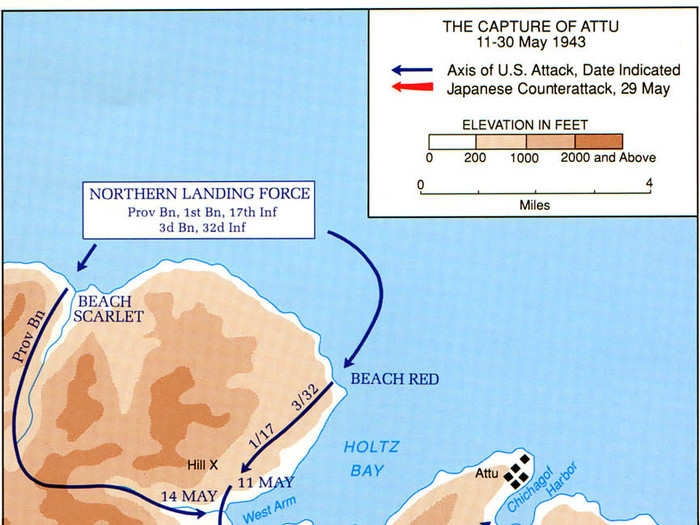

Storms and poor visibility also delayed the landings on Attu by several days, and US troops did not go ashore until May 11, 1943. Poor weather hindered the landings. It also helped conceal the Japanese defenders.

Source: US Army

Progress was slow for the next week, as US force dealt with poor communications and faced both Japanese resistance and weather conditions that prevented air support.

Much of the fighting was in close quarters, done in dense fog and winds of up to 120 mph. The Japanese used the rough terrain to their advantage. "It was rugged...the whole damned deal was rugged, like attacking a pillbox by way of a tightrope... in winter," US Army Lt. Donald E. Dwinnell said.

The weather conditions and remoteness of the fighting complicated resupply efforts. Some US troops went days without food when resupply planes couldn't find them in the thick fog.

Some US soldiers on the beachs threw grenades into the ocean in hopes of catching fish, while troops who overran Japanese positions would sometimes fight over the food and ammunition left behind.

Source: US Army, National Park Service

A break came on May 18, when the Japanese withdrew to Chichagof Harbor.

By May 28, the US held three important hills in the Chicagof Valley: Fish Hook, Buffalo, and Engineer. On May 29, the roughly 1,000 remaining able-bodied and wounded Japanese launched a counterattack against Engineer Hill, planning to capture US supplies and artillery before retreating into the mountains to wait for reinforcements.

Many of the Japanese involved saw the attack as an opportunity to die an honorable death rather than a chance for victory.

"The last assault is to be carried out. All the patients in the hospital are to commit suicide. Only 33 years of living and I am to die here," wrote Dr. Paul Nebu Tatsuguchi, a Japanese medic. "At 1800 (hours) took care of all the patients with grenades. Good-bye, Taeki, my beloved wife, who loved me to the last."

The Japanese attack startled US troops on Engineer Hill, and many retreated.

"What a nightmare, a madness of noise and confusion and deadliness," Army Capt. George S. Buehler said of the fighting.

William Roy Dover's first sergeant woke him in his pup tent around 2 a.m., when word came the Japanese were attacking and might have gotten behind the US front line.

"He was shouting, 'Get up! Get out!'" Dover told the Associated Press. "I had two friends that were too slow to get out," the 95-year-old said. "They both got bayonetted in their pup tents."

Dover's sergeant "was running up and down trying to get people out of their tents shouting, the 'Japs are coming,'" he said. "Of course, he got shot and killed."

"The Japanese had the cover from the fog," Dover told Alaska CBS affiliate KTVA. "They could shoot down from the mountain and shoot the infantry. The infantry had it real rough. We lost a lot of good men. When they broke through on the banzai raid on May the 29, they came a-screamin' and a-hollerin'. It was in Japanese so I have no idea what they were saying but it was chilling to hear."

Source: National Park Service

A force of medics, engineers, and other support personnel mounted a frantic defense, throwing grenades at the advancing Japanese.

Hand-to-hand fighting ensued, but the tide turned when the US Army's 50th Engineers arrived, using rifle butts and bayonets to keep the Japanese away from artillery pieces on the hill.

"It caught us off balance because we were not anticipating anything of that nature," Joseph Sasser, then a 20-year-old soldier from Cartharge, Mississippi, told KTVA. "I heard someone yell, 'the Japs are coming.' They came across the valley. If they were able to walk, they came to fight and give up their lives."

Sasser was perched against the berm of a hill when a captain took position with a rifle about 10 feet away. "I noticed about after 30 minutes or so, he was awfully quiet," Sasser said. "We checked to see if he had a pulse and if he was alive, and he was not. We didn't even know he had been shot."

Source: National Park Service

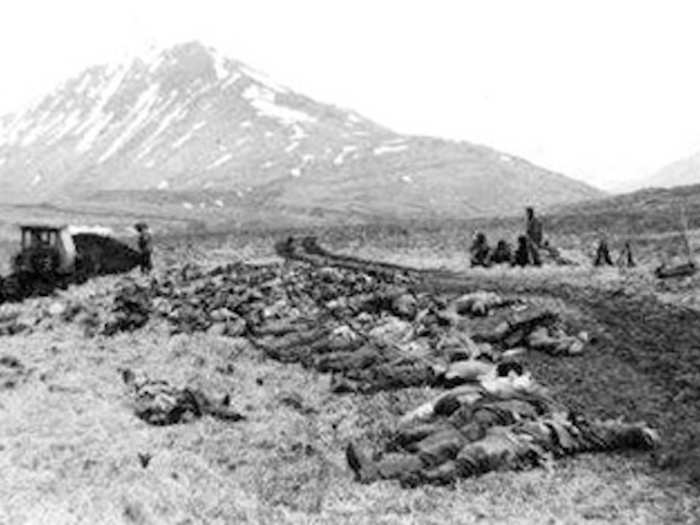

Hundreds of Japanese troops were killed in the assault, and hundreds more took their own lives, many by holding hand grenades to their chests.

When US troops found Japanese field hospitals, they discovered that doctors had killed the wounded. On May 30, only 28 of the roughly 1,400 Japanese in the area the day before were still alive.

"Some of them had grenades wrapped around their heads, so they could pull the pin and kill themselves, and at the same time, I get nervous talking about it," Allan Seroll, a member of the Army Signal Corps on Attu, told KTVA. "They wanted to kill as many Americans as they could."

"There were medics out there trying to help the wounded, the wounded were worthless to the fight, yet, the Japs ran up to them and killed them and the medics with their bayonets," he said. "Just ridiculous, and I'll never forgive them for that. It was unnecessary."

Surrender was considered dishonorable by the Japanese. Attu saw the first official case of "gyokusai," a Japanese euphemism for annihilation or mass suicide in the name of Emperor Hirohito.

Source: Associated Press, National Park Service

US troops reclaimed Attu on May 30, 1943.

They found 2,351 enemy dead; only 28 surrendered. Of the 15,000 US troops involved, 549 were killed and 1,148 were wounded.

The battle for Attu was one of the most deadly of World War II in the Pacific. For every 100 enemy troops on the island, about 71 US personnel were killed or wounded, making the cost of taking Attu second only to the attack on Iwo Jima.

Source: Associated Press, US Army

More US troops fell to the elements than did to enemy fire — 2,100 were put out of action by disease or noncombat injuries.

Prolonged exposure to cold, wet conditions in poorly made boots left many US soldiers with trench foot, which could lead to gangrene or amputation if untreated.

"The ones who suffered were the ones who didn't keep moving ... They stayed in their holes with wet feet. They didn't rub their feet or change socks," Capt. William H. Willoughby said.

Source: National Park Service

The lessons of Attu were applied to the assault on Kiska, called Operation Cottage.

US troops, many now experienced, received better clothing and equipment.

A bigger force was prepared to face what was believed to be a greater Japanese force on the island. Aerial and naval bombardment was conducted throughout July and early August.

US and Canadian troops started going ashore on August 15, but they encountered no resistance. The 5,200 Japanese on Kiska has been evacuated weeks before — totally undetected. The island was declared secure on August 24.

Source: US Army

Activity and troop levels were reduced in the Alaskan theater after Kiska was retaken, but the campaign had an important impact on the war.

Combat-related exposure injuries there led the Army to issue new gear. Planes from the US 11th Air Force based in the Aleutians launched attacks on the Kuril Islands, and the Japanese, seeing the US presence in the Aleutians as a threat, increased their air and naval forces in northern Japan, giving US troops in the South and Central Pacific an advantage.

John Haile Coe, a historian and author of "Attu: The Forgotten Battle," told the AP that the Army took lessons from the amphibious landings it performed on Attu and from the Japanese tactics it encountered there.

But the 19-day campaign on Attu — the only World War II battle fought on North American soil — has faded from memory.

"The Battle of Attu is the forgotten battle," retired Executive Director of Alaska Veterans Museum Col. Suellyn Wright Novak told Alasaka CBS affiliate KTVA. "The battle of Attu has a lot of ramifications, but those guys who fought in it are the forgotten heroes."

Source: US Army, National Park Service

"I wake up in the middle of the night, and I can't go back to sleep," said Seroll, the now 102-years-old Army signalman. "That's what this has done to me. That's how much it affected me and still does."

Source: KTVA

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement