- Home

- international

- news

- Locals throw baby puffins off clifftops on a remote island in Iceland to help the stray birds take flight

Locals throw baby puffins off clifftops on a remote island in Iceland to help the stray birds take flight

James Pasley

- Iceland's remote Westland Islands are home to the world's largest puffin colony.

- Every year, puffin chicks get disorientated by light pollution and crash inland rather than flying out to sea.

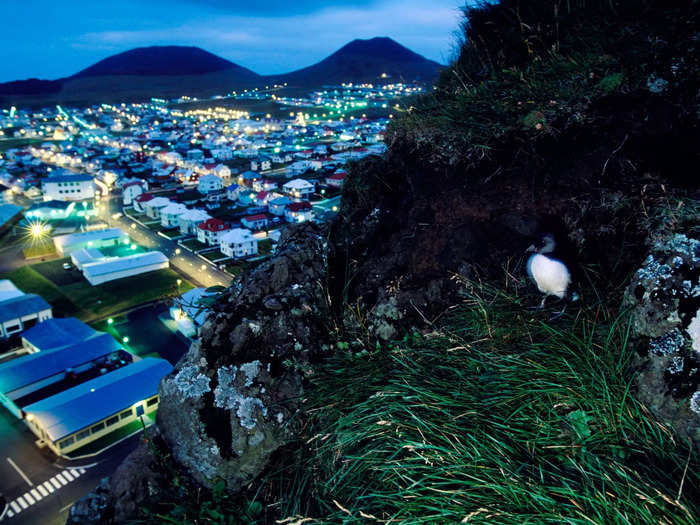

Every year during the late summer, locals on a remote island off the coast of Iceland spend their evenings searching for disorientated puffin chicks — known as pufflings — and throw them off a cliff's edge.

Light pollution can confuse the pufflings, causing them to fly inland instead of out to sea.

Puffins are a national treasure in Iceland, which has the largest colony in the world, but for decades, their numbers have been dwindling.

About 43 miles off the southern coast of Iceland are the Westman Islands, a collection of windswept, volcanic remote islands.

Sources: NPR, Smithsonian Magazine, New York Times

The largest of these islands is called Heimaey. It covers about five square miles and is the only inhabited island with a population of about 4,400 people.

Source: Smithsonian Magazine

The Westland Islands are known for two things. The first is a violent, unexpected volcanic eruption that occurred in 1973 after the volcano had lain dormant for 7,000 years.

Source: New York Times

The second is its puffin population. The islands are home to the world's largest puffin colony. At certain times of the year, the skies are filled with puffins carrying fish to their chicks.

Source: Smithsonian Magazine

Puffins are recognizable by their black and white feathers and their clown-like orange beaks. Unlike most seabirds, they have dense bones allowing them to dive 200 feet deep to catch fish.

Source: Smithsonian Magazine

Puffins are Iceland's most common bird, but for the last 20 years, they have struggled to breed, according to Erpur Snaer Hansen, director of ecological research at the South Iceland Nature Center.

He told Audubon they had suffered a "breeding failure, basically."

Sources: Audubon, New York Times

Breeding pairs have dropped significantly since the 1990s, and for over a decade, there were few newborn chicks. In 2018, the islands' puffin population had fallen from 7 million to an estimated 5.4 million.

Sources: New York Times, Audubon

A number of factors are likely responsible, including climate change, overfishing, pollution, and difficulty finding food.

Source: New York Times

Reduced populations of sand eels due to increasingly warm sea temperatures have particularly hurt puffins, forcing them to search further for food for their chicks.

If puffins can't find enough food, they feed themselves over their pufflings, which means scarcity can be a puffling-killer.

Hansen said the relationship was comparable to that of "the hare and the lynx."

Sources: New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Audubon

It can be hard to believe puffins in Iceland are struggling since they appear plentiful. But because puffins live for 25 years, it takes years to notice falling numbers.

Sources: New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Audubon

Puffins used to be a vital food source and a delicacy for locals and tourists, but hunting restrictions are now in place due to the population's breeding failures.

Sources: Smithsonian Magazine, Audubon

In 2021, things appeared to be looking up after the colony produced about 700,000 new chicks, but by the middle of the summer, almost half had died, mostly from starvation.

Sources: Smithsonian Magazine, Audubon

Growing the puffin population isn't helped by the fact they only lay one egg each season. They mate with the same puffin for life and usually go back to the same burrow.

"If you have one failed generation after another after another after another, the population is through, pretty much," Rodrigo A. Martinez, who works with the South Iceland Nature Research Center told NPR.

Sources: Smithsonian Magazine, Audubon, NPR

For most of the year, puffins live out on the freezing waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. They live alone, bobbing in the water, diving deep for food.

Sources: Smithsonian Magazine, Iceland Magazine

In late spring, millions of puffins return to breed in the cliffs of these islands.

Sources: Smithsonian Magazine, Iceland Magazine

After the puffling hatches, the parents raise it for about 40 days. Then the parents return to the ocean, leaving their puffling to fend for itself.

Sources: NPR, Iceland Magazine

When the puffling gets hungry, it will leave the burrow and fly out over the ocean in search of food.

Sources: NPR, Iceland Magazine

But pufflings — who use moonlight for guidance — often get disorientated by artificial lights from town and fly inland instead. This is where puffin tossing comes in.

Sources: Smithsonian Magazine, NPR

Toward the end of summer, locals assigned to "puffling patrol" search the streets at night for chicks that have lost their way.

They're often found under cars, in bins, or in piles of fishing nets and ropes down at the harbor.

Sources: Audubon, NPR, Smithsonian Magazine

It's vital that they help the pufflings by tossing them off the edge of a cliff. When they launch off cliffs, the birds use the sea winds and distance below as a makeshift runway, but if they crash into the town, their wings aren't strong enough to get them airborne again.

Without any human help, they are left to fend for themselves and are unable to escape predators or find food.

Source: Smithsonian Magazine

According to one 86-year-old resident named Svavar Steingrimsson, these patrols have been going on since the beginning of the 20th century when the island first got electricity.

Source: Smithsonian Magazine

The patrols are famous in Iceland, even if they aren't as successful as they used to be.

Source: Smithsonian Magazine

About 25 years ago, you could save 100 pufflings every night, according to local Valur Mar Valmundsson. Now, you're lucky to find that many over the whole season.

Source: Smithsonian Magazine

Once the puffling's data has been recorded, it's taken to the top of cliffs and thrown off the edge.

People could let them fly away in their own time, but Kyana Powers told NPR most people like to actually throw them off.

Source: NPR

And despite how crude it looks, puffling tossing really is for their own good.

Source: NPR

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement