When Things Go Wrong At 20,000 Feet... One Of The Most Remarkable Survival Stories Ever

The approach to Siula Grande is a two-day hike from the nearest road.

The climbers, Joe Simpson and Simon Yates, establish a base camp about 4-5 miles from the mountain. Then, early in the morning, they set off...

DAY ONE...

The route to the mountain passes a glacial lake, followed by a long hike up a valley and over the glacier itself.

Simpson and Yates climb "alpine style," with no fixed ropes or camps. They carry everything they think they will need. They intend to climb up and down the mountain in a three-to-four day push.

The drawback of "alpine style" in the wilderness is that if something goes wrong, there's no chance of a rescue. You're on your own.

The western face of Siula Grande has never been successfully climbed. It has been attempted, however, which is part of the appeal.

Day one goes well. Good weather. Clean snow and ice.

In the evening, about halfway up the mountain face, Simpson and Yates dig a snow cave and camp.

Climbing at high altitude leads to severe dehydration, so the climbers have to melt lots of snow for water. They're carrying a very limited amount of food and fuel.

DAY TWO...

The weather deteriorates.

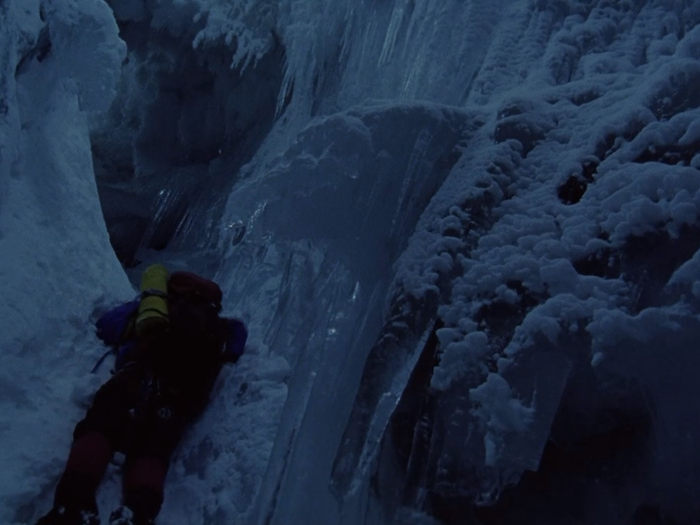

And the climbing becomes difficult, exhausting, and dangerous.

It's exhausting to climb vertical ice, snow, and rock, even at sea level. At 18,000-20,000 feet, your heart races, and you gasp for breath.

As Simpson and Yates near the top of the face, they run into real trouble.

Deep powder snow clings to extremely steep slopes. They have to fight their way upward, with nothing to hang onto.

The climbing is so difficult that they progress only a few hundred feet in 5-6 hours.

Darkness has fallen, and the wind chill is brutal, so they dig another snow cave and spend a second night on the face.

DAY THREE

The weather has cleared. The climbers see what has been giving them such trouble.

Andean snow formations called "flutings," which are famously dangerous and difficult.

Simpson and Yates continue upward. By mid-day on their third day of climbing, they reach the summit ridge.

Exhausted, but relieved, they follow it to the summit.

Upon reaching it, they become the first climbers to successfully scale the west face of Siula Grande.

Then, behind schedule, low on food and fuel, they head down quickly, knowing that most climbing accidents happen on the descent.

Again, the weather quickly deteriorates. Soon the climbers are lost in a white-out.

The conditions are so treacherous that Yates falls through a cornice and off the ridge. The rope stops his fall, and he struggles back up.

Soon thereafter, the climbers decided to bivouac again.

That night, their third on the mountain, they use the last of their fuel.

DAY FOUR: The next morning, the weather is clear. Simpson and Yates are still high on the mountain, but the toughest section of the ridge is behind them. They began to think they have the climb "in the bag."

Then Simpson reaches a section of the ridge that drops off sharply. He turns around to descend it, using his ice axes for holds.

Near the top, unhappy with his left-hand axe placement, he removes the axe from the ice to reset it.

Suddenly, the right axe gives way.

Simpson falls, landing with his right leg fully extended. The impact drives his lower leg bone through his knee joint, shattering his knee.

The pain is excruciating.

Simpson's first thought, at 20,000 feet on a remote mountain ridge, is "I can't have broken my leg. If I've broken my leg, I'm dead."

When the shock of pain has subsided, he tries to stand on the leg, hoping he has just torn ligaments. He hears the bones grind and collapses in pain.

Above, oblivious to what has happened, Yates follows the rope forward. When Simpson relays the news that his leg is broken, Yates's first thought is, "We're stuffed. We're going to be doing well if either of us get out of this now."

Yates gives Simpson some pain killers. Simpson assumes that Yates will then leave him. They are out of food and fuel. They can't stay where they are. No help can reach them. And Simpson can't move. So, what else could Yates do?

To Simpson's surprise, however, Yates does not leave. Rather, he starts to dig a seat in the snow. Then he sits in it and sets about lowering Simpson down the ~3,000-foot face.

The climbers only have two 150-foot ropes. They tie them together. Simpson lies on his belly. Yates sits above him and lets out the rope. Simpson begins sliding down the face on his belly.

Simpson slides feet first. Fast. Every time his shattered leg hits the snow, he feels a shock of excruciating pain.

When Simpson has reached the end of the first 150 foot rope, Yates tugs the rope. Simpson sets his ice axes and takes his weight off the rope. Yates unhooks the rope and moves the knot through his belay plate. Then he lowers Simpson another 150 feet on the second rope.

When they reach the end of the second rope, Simpson sets himself, and Yates starts climbing down. Then Simpson stands on his good leg and begins digging another snow seat. When Yates reaches him, they repeat the lowering process again. And again. And again...

The weather remains terrible. Once again, night begins to fall.

Remarkably, the climbers repeat the lowering process successfully around 10 times. They are nearing the bottom of the face, about to finish a miraculous and heroic escape. But, once again, something goes wrong.

On his belly, sliding fast, Simpson feels the snow beneath his elbows turn to ice. The steepness of the slope increases, and he begins to accelerate. Realizing what is happening, he screams at Yates to stop the rope. But the wind is so strong that Yates can't hear him.

The slope gets steeper and steeper. Simpson tries frantically to stop himself.

But then he sails off the edge of an overhanging cliff.

When the end of the first rope reaches Yates's belay plate, Simpson's fall suddenly stops. He finds himself hanging in mid-air, about 80 feet above the glacier at the bottom of the face.

Directly below him, Simpson can see the mouth of a gigantic crevasse.

Simpson pulls himself to a sitting position on the rope and tries to reach the face of the cliff with his ice-axe. The cliff is steeply overhanging, and the face is too far away to reach.

Simpson yells up to Yates, who has no idea what has happened. The storm is raging, and Yates can't hear him.

Yates tugs on the rope--the signal for Simpson to take his weight off so Yates can move the knot through the belay plate. Simpson, hanging in mid-air, can't take his weight off. Still unaware of what has happened, Yates just hangs on.

150 feet below Yates, hanging in mid-air, Simpson realizes that his only chance is to find a way to climb up the rope to the top of the cliff.

He takes his gloves off and tries to use his frozen hands to tie knots in small pieces of rope that might allow him to ascend the main rope.

He gets the first ascender knot tied, and then goes to work on the other one. In the freezing wind, his hands are like clubs.

He almost gets the second ascender tied... and then he drops it.

And that's it. There is simply nothing else Simpson can do.

Meanwhile, hundred and fifty feet up the mountain, Yates' position is becoming increasingly desperate. He is exhausted and freezing. And his snow seat is beginning to collapse. Yates can feel it giving way beneath him.

Below, Simpson can feel the rope jerk lower as Yates' seat begins to give way. He thinks that Yates will soon lose his grip on the mountain and "come off," sending them both plunging toward the glacier below.

But there is nothing that Simpson can do about this. Helpless, freezing, he just hangs at the end of the rope, "waiting to die."

Somehow, Yates holds on for an hour and a half. He still has no idea what has happened to Simpson. He can't understand why Simpson hasn't taken his weight off the rope. All he knows is that he can't hold on much longer.

Yates' seat is also continuing to crumble. He knows it is only a matter of time before it gives way. When it does, he'll fly off the mountain, and they'll both die (if Simpson isn't dead already).

Then Yates remembers that he has a pen-knife in the top of his pack. He makes the decision instantly. He shifts the rope to one hand and uses the other to fumble for the knife...

He finds it. And opens it.

And he cuts the rope that is holding Joe Simpson.

Then Yates collapses backward into the snow, exhausted.

Down below, Simpson is falling 80 feet through the air.

He hits the "glacier," only to smash through a thin snow bridge...

...and he plunges into the gigantic crevasse.

Up the mountain, still clinging to the face, Yates digs himself a snow cave. He crawls into his sleeping bag and spends a fourth and awful night on the mountain, sure that his friend and partner is dead.

Sometime later that night, Simpson comes to. Gradually, he realizes that he's not dead.

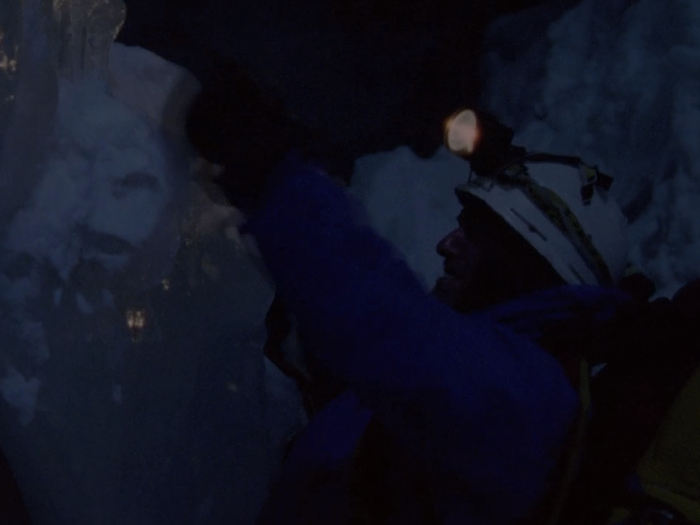

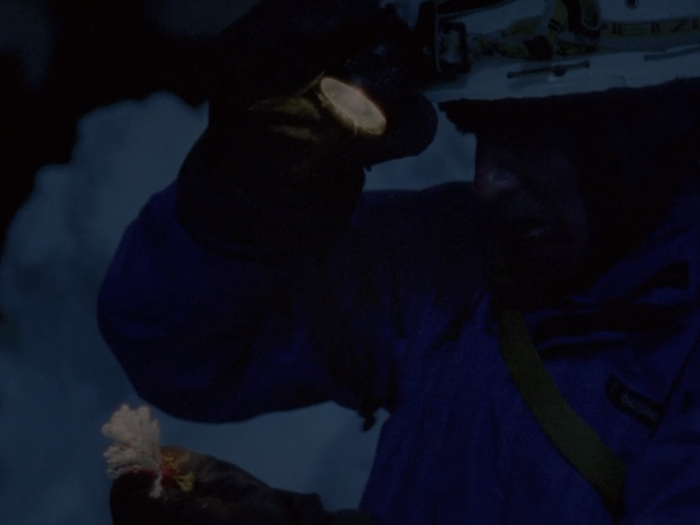

He has no idea where he is, though, so he switches on his headlamp.

He discovers that he is lying on a thin ice ledge about 80 feet deep in the crevasse. He isn't at the bottom of the crevasse. He is on a ledge. He has fallen 160 feet and somehow, miraculously, survived. He has also landed in the only place possible. If he had fallen a couple of feet to the right or left, he would have plunged to his death.

Simpson screws himself in.

Then he hauls in his rope, which extends upwards to the hole he fell through, about 80 feet above him. He assumes that Yates has fallen off the mountain and landed beyond the crevasse on the glacier. So he expects to feel the rope become taut as he pulls against Yates' body. But it doesn't.

Then he gets to the end of the rope and finds that it has been cut.

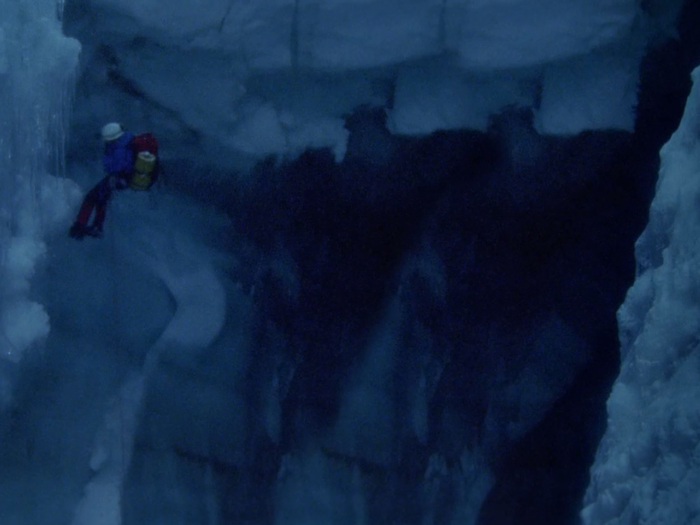

He tries to climb out of the crevasse, but the only route out is 80 feet of vertical ice. He couldn't climb that with two good legs, let alone one.

Devastated, angry, exhausted, and feeling utterly alone, he settles in to wait for morning.

DAY FIVE

The next morning, Simon Yates emerges from his snow hole, and rappels down the last part of the face. As he descends, he passes the cliff that Simpson fell over, and he finally understands what happened. He also sees the enormous crevasse at the base of the cliff and becomes certain that Simpson is dead.

Weeks later, back in Britain, Yates will be heavily criticized by the mountaineering community for cutting the rope on his partner. But both Simpson and Yates agree that Yates had no other choice. One mistake that Yates does make is not spending more time the next morning yelling into the crevasse to make sure that Simpson is dead. In Yates' defense, he is desperately exhausted, starved, and dehydrated. Devastated, he heads back down the glacier, alone.

Deep in the crevasse, Simpson wakes up covered with new snow. Perversely, discovering that the rope had been cut has given him hope: It means that Yates had not fallen off the mountain and, therefore, might be able to rescue him. For several hours, clinging to the ledge, Simpson yells for help. By 10am, he knows that it isn't coming.

Simpson can't go up: There is no scaling a wall of vertical ice with only one leg. With no food or water or any expectation of help, he also can't stay where he is. So, gradually, he realizes that there is only one thing he can do. It means almost certain death. But almost-certain death is better than the alternative.

He ties himself in and starts to lower himself down deeper into the crevasse.

He slides down the slope of his ledge.

And over the edge.

He hasn't tied a knot at the end of the rope. (Why bother? If he gets to the end of it without hitting anything, he's dead regardless.)

Down, down, down...

Until, suddenly, he sees that he's coming to some sort of a bottom.

Only it's not the bottom. It's another thin snow bridge. And as he crawls across it, he can hear ice falling beneath him. But he keeps crawling. Because on the far side of the bridge, he sees something he can hardly believe. A climb-able slope leading to a hole with the sun shining through it, a couple of hundred feet above.

Simpson makes it across the snow bridge and begins hauling himself up the slope.

Setting his axes, he propels himself up with his arms and his one strong leg...

For hours, he makes slow but steady progress.

Then, early that afternoon, he pokes his head through the snow hole and hauls himself out into the sun, feeling reborn.

The sun feels wonderful, and he lies in it and soaks it up. But then he realizes that his predicament is almost as dire as before.

He has been climbing for five days. He has no food or water. His right leg is shattered. And he is five miles from help.

Five miles of extraordinarily dangerous and difficult terrain.

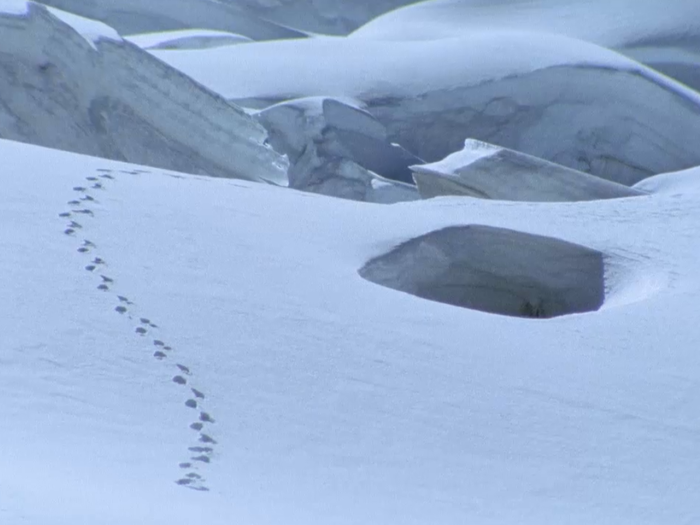

The distance seems impossibly long. But he sees Yates' footprints leading away down the glacier. So he picks a point a couple of hundred yards away. And he gives himself 20 minutes to reach it...

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement