Since 2007, a variety of projects have started as part of the Great Green Wall, including growing gardens in Senegal.Zohra Bensemra/Reuters

- The Great Green Wall is a project to restore degraded land in nearly two dozen African countries.

- Deforestation, agricultural expansion, and drought have caused desertification across the continent.

Over the past several decades, deforestation, agricultural expansion, and drought have all contributed to desertification in parts of the African continent. Once-fertile soil has become drier and less productive.

More than a dozen African countries have been fighting this desertification with an ambitious project to grow trees and other vegetation on 247 million acres of degraded land, an area roughly 2.3 times the size of California.

The goals of the 17-year-old Great Green Wall project — estimated to cost between $36 to 49 billion — also include generating 10 million jobs and sequestering 250 million tons of carbon by 2030.

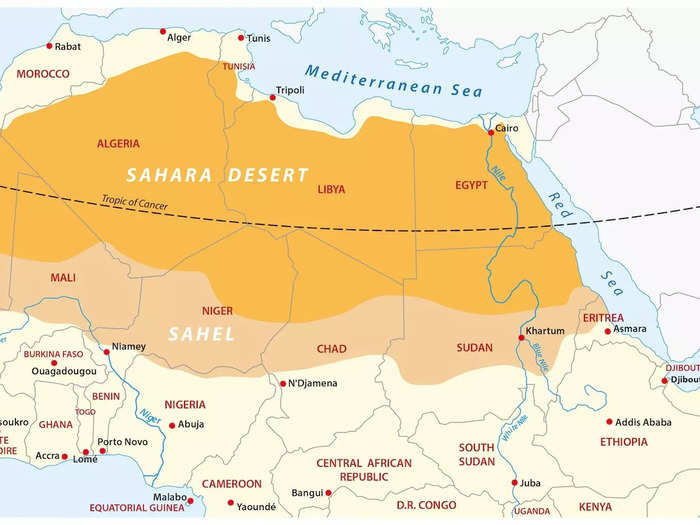

Countries from Senegal to Djibouti are trying to regreen the semiarid Sahel bioclimate, a band stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea.

The dangers of land degradation include soil erosion and lessened biodiversity.

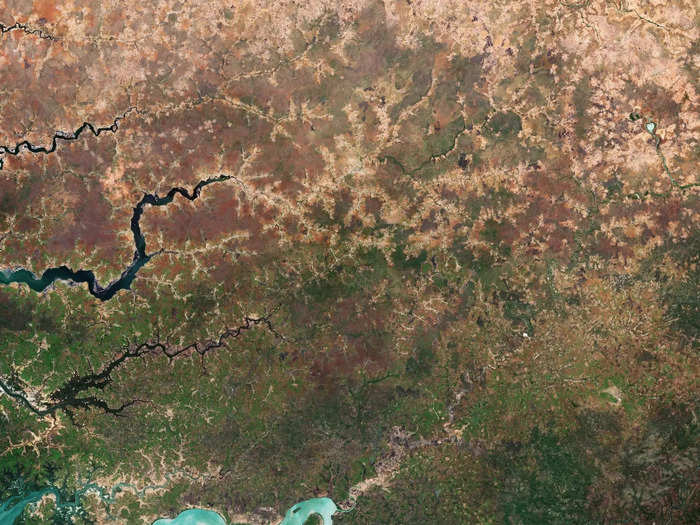

Side-by-side images of the Ferlo region of Senegal in 1994 and 2011 show land degradation over nearly 20 years. G. Gray Tappan/US Geological Survey

West African forests once covered over 50,000 square miles. Since 1975, deforestation, mainly from agricultural expansion, reduced the size to about 32,000 square miles, according to the US Geological Survey.

In addition to making soil less fertile, desertification can make it more prone to wind erosion and less able to retain moisture. It also leads to a loss in biodiversity of plant and animal species. All of these factors make it more difficult for human populations to survive.

The Great Green Wall initiative launched in 2007 as a plan to plant trees across a large swath of the African continent.

The Sahel is a bioclimate stretching across the African continent from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea. Rainer Lesniewski/iStock/Getty Images

The African Union formally began the project in 2007. Originally, the GGW included 11 countries — Burkina Faso, Chad, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, and Sudan. In the years since it started, a handful of others have joined as well.

At first, the plan was to fill a 10-mile-by-4,350-mile area of the Sahel with trees. Trees can help slow soil erosion, absorb carbon dioxide, and promote biodiversity by providing food and shelter for animals.

However, critics started pointing out flaws, and the project hit several speedbumps.

The GGW project hit some early snags.

Some trees planted as part of the GGW didn't survive because they were located in uninhabited areas. Seydou Diallo/AFP via Getty Images

One big problem with the tree-planting plan was the trees themselves. Some saplings either grew poorly or died. They were planted in remote regions, which made them difficult to care for. Warmer temperatures and low rainfall also contributed to the problem.

Some communities thought their government hadn't fully involved local and indigenous populations in their projects. Other governments had purposefully removed groups of people from their homes in forests and conservation areas, Corporate Knights reported.

The success of the GGW has also been difficult to monitor in some areas, according to Corporate Knights. External experts have had trouble independently verifying some governmental data, for example.

By 2020, the project was only 4% completed.

In 2021, world leaders, including France's Emmanuel Macron, pledged $19 billion as part of the Great Green Wall Accelerator to help measure and facilitate the project's success.

By then, GGW's focus had started to shift to a mix of projects that drew on traditional growing and irrigation methods.

Niger and Burkina Faso found success with different approaches outside the GGW project.

After droughts in the last century, farmers in parts of Niger started returning to traditional practices to keep soil fertile. Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images

Before the GGW project began, locals in parts of Niger and Burkina Faso started using a technique called farmer-managed natural regeneration, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

French colonial authorities had once encouraged farmers to remove trees on agricultural land, according to Yale Environment 360. Droughts in the 1980s prompted the shift back to earlier methods.

Instead of planting new trees, farmers in south-central Niger encouraged the growth of existing shrubs and trees. The practice has helped regreen 12 million acres and grown 2 million trees.

In Burkina Faso, farmers drew on traditional knowledge to adapt after droughts in the 1970s and 1980s. They dug deep pits called zai and assembled stone barriers to help capture and retain moisture.

One farmer, Yacouba Sawadogo, was so successful that a film was made about his work in 2010, called "The Man Who Stopped the Desert."

The GGW isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach.

A Tolou Keur circular garden in Boki Diawe, in Matam region, Senegal, part of the Great Green Wall. Zohra Bensemra/Reuters

Since the start of the GGW, many countries have seen success with farmer-led projects. In Senegal, farmers started planting zai gardens during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Known as Tolou Keur in Wolof, the country's language, the half-moon pits hold and direct water toward plants.

While not all the Tolou Keur have survived, others are thriving. Farmers are growing everything from sorghum and millet to mint and hibiscus plants.

Part of their attraction lies in the fact that they're quick to build, don't take up a lot of space, and only need about 10 people to maintain them, according to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification.

The GGW is now a mosaic instead of a wall of trees.

The Sahel village of Ndiawagne Fall in Kebemer, Senegal is part of the Great Green Wall project, which originally focused on planting trees across the Sahel. Leo Correa/AP Photo

At this point, the Great Green Wall is a bit of a misnomer.

"We moved the vision of the Great Green Wall from one that was impractical to one that was practical," Mohamed Bakarr, the lead environmental specialist for Global Environment Facility, told Smithsonian Magazine in 2016. "It is not necessarily a physical wall, but rather a mosaic of land use practices that ultimately will meet the expectations of a wall."

The project incorporates technology like drones and satellite imagery.

Satellite imagess, like this one from the Copernicus Sentinel-2 mission, can help track the progress of the GGW. European Space Agency

Drones and satellites recently started providing detailed information on restored land, using AI to identify the species of individual trees.

Tech startups and organizations like the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) are collaborating to help Sahel communities map and track the populations of baobab trees, which can help reduce soil erosion.

Many countries have seen success regreening areas of the Sehal.

An expanse of trees outside the Walalde department in Senegal. Zohra Bensemra/Reuters

Ethiopia, Niger, and Senegal have all regreened parts of their land. In addition to its zai gardens, Senegal planted 50,000 acres of trees, according to National Geographic.

In 2023, the UN Development Programme reported that the GGW project was 18% completed, restoring over 49 million acres of land and creating 350,000 jobs.

But not all countries have seen the same amount of success.

With 2030 approaching, the GGW is facing setbacks.

Some countries like Sudan haven't been able to make as much progress on GGW goals due to unrest and less funding. Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah/Reuters

Conflict and instability in some countries make meeting the GGW's goals difficult as residents move to avoid fighting. More resources also seem to go to stabler countries, while Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, and Sudan receive less investment from donors, according to Nature.

Yet with the climate crisis and expanding population, the GGW's mission remains as pressing as ever.