Photos show ancient Egyptian artifacts and skeletons found in a 'lost golden city' built by King Tut's grandfather

Aylin Woodward

- Egyptian archaeologists have unearthed a 3,400-year-old "lost golden city" in Luxor over the last seven months.

- In 1935, a French excavation team searched for the city - which may be the largest ever built in Ancient Egypt - but never found it.

- The city, named "tehn Aten," or the dazzling Aten, was built by Amenhotep III, King Tut's grandfather. He is considered the wealthiest Pharaoh who ever lived.

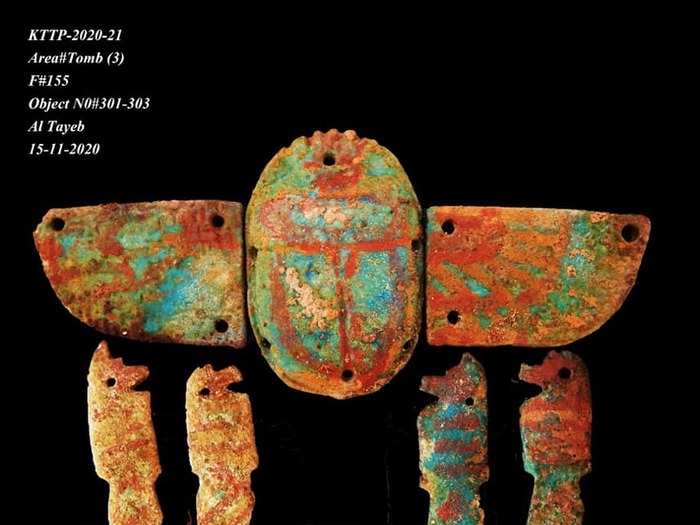

- Photos from the site show colored pottery, scarab-beetle amulets, jewelry, wine caskets, mud bricks, and an ancient bakery. Only one-third of Aten has been uncovered so far.

On the banks of the Nile River, 300 miles south of Cairo, sits the city of Luxor. It's adjacent to Egypt's Valley of the Kings, where archaeologists discovered King Tutankhamen's tomb a century ago.

Somewhere nearby, King Tut should have a mortuary temple, where priests and relatives left gifts and tribute for the pharaoh to enjoy in the afterlife. But it was never found.

In September, archaeologist Zahi Hawass, the former Egyptian minister of antiquities, set out to find it.

Hawass' team began searching an area of Luxor where Tut's successors, Ay and Horemheb, built their mortuary temples. But instead of Tut's temple, they uncovered an enormous, well-preserved metropolis.

Within weeks of the start of their dig, Hawass' team uncovered mud bricks stamped with Pharaoh Amenhotep III's name. That helped them estimate the city was built 3,400 years ago, since Amenhotep III ruled between 1391 BC and 1353 BC.

"I called the city 'the golden city' because it was built during the golden age of Egypt," Hawass told Insider.

Amenhotep III was King Tut's grandfather, and "the wealthiest Pharaoh who ever lived," according to Betsy Bryan, an Egyptologist from Johns Hopkins University.

Amenhotep III ruled during a time of peace, which helped him amass unprecedented wealth, Bryan told Insider.

"He was never at war. All he did was sit back and count money for 40 years, so he built constantly," she said.

Archaeologists knew the Pharaoh had funneled some of his riches into building a city in this area of Egypt: "This is a place we knew existed," Bryan said. But its precise location had eluded diggers for almost a century.

"Many foreign missions searched for this city and never found it," Hawass said in a press release, adding it may be the largest ancient city ever found in Egypt.

In 1934 and 1935, a French excavation team searched Luxor for the "lost golden city" but came up empty, Hawass said.

That effort failed because the French archaeologists had been looking in the wrong place, Hawass added. Figuring the city would be clustered around buildings dedicated to the Pharaoh who built it, the group searched next to the Collosi of Memnon: twin statues that depicted Amenhotep III. The Pharaoh's mortuary temple was nearby as well — but they had no luck finding the city.

"It never occurred to them to look slightly south," Bryan said.

The lost city, it turns out, was located to the south and west of Amenhotep III's mortuary temple.

So far, Hawass' team has uncovered remnants of the city in an area that's at least half a square mile.

But the city is likely far larger, Bryan said, stretching all the way to the Pharaoh's palace at Malkata, which is almost 2 miles south of the Colossi of Memnon.

In addition to the city's size, Hawass said, "the huge amount of artifacts" his team uncovered there makes this an unprecedented archaeological find.

"It will give us a rare glimpse into the life of the ancient Egyptians at the time where the empire was at its wealthiest," he said in a press release.

The city's streets are flanked with buildings, some of which have walls 9 feet tall.

Scattered throughout those structures, Hawass' team found rooms filled with pottery, glass, metalwork, and weaving tools. Ancient Egyptians once used these objects in their day-to-day lives, but the tools had lain untouched for millennia.

Hawass' excavation team also found a large cemetery north of the city.

They haven't figured out how big the cemetery is yet, but the team discovered a cluster of underground tombs with stairs leading to each tomb entrance.

In one part of the cemetery, the diggers found a grave holding a skeleton with a rope wrapped around its knees.

Hawass is still investigating why the body was buried in this manner.

The city seems to be divided into industrial and residential areas. In the south, archaeologists found an ancient bakery with a cooking and meal-preparation area, ovens, and pottery used for storing food.

Another neighborhood had multiple workshops: one for producing mud bricks used to build temples, and another for producing amulets.

Another part of the city was all houses.

"For those of us interested in the people and how they did stuff, this place is a treasure trove," Bryan said.

Nearby the cemetery, Hawass' team found a piece of pottery containing 22 pounds of dried meat, likely from a butcher at a slaughterhouse.

The vessel had an inscription indicating that the meat was for a festival celebrating the continued rule of Amenhotep III.

The city dwellers were skilled craftsmen, Bryan said - they made fancy ceramic vessels, glassware, and temple decorations in the name of Amenhotep III.

"It really is like peeking into the king's private storage unit," she said. "That kind of specialization was rarely seen anywhere."

Hawass' team also uncovered scarab-beetle amulets, rings, and wine caskets in the city.

According to Bryan, the city was Amenhotep III's love letter to the god Aten.

"When ancient Egyptian kings built, they would dedicate their construction to a deity and associate themselves with that deity," she said.

Aten was depicted as a sun disc. Archaeologists typically associated the deity with Amenhotep III's son, Akhenaten, who worshipped Aten instead of the chief Egyptian god of the sun and air, Amon.

This discovery shows that Amenhotep III believed in Aten too, Hawass said — which explains why the Pharoah named the city "tehn Aten," meaning the dazzling Aten.

After taking over from his father, Akhenaten - King Tut's father - briefly lived in Aten. Then he moved 250 miles north to a city called Amarna, along with his people. That's where King Tut was born.

Akhenaten's exodus to Amarna could be why so many tools and artifacts were left behind in Aten.

"When you pick up and move, you're not going to take the ceramics," Bryan said.

According to Hawass, Akhenaten fled to Amarna and built that city to escape the priests of Amon, who were displeased that their Pharaoh was worshipping a different god than their own.

Akhenaten was branded a heretic. Following his death, King Tut's family moved to Thebes, another city in the Luxor area that served as the ancient Egyptian capital.

It's unclear whether Aten was ever reoccupied.

Hawass said there's plenty more to find of the "lost golden city," since only one-third of it has been uncovered so far.

"We still think that the city has an extension to the west and to the north, and that is our goal by next September," Hawass said.

READ MORE ARTICLES ON

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement