The reporter at ARCpoint Lab in Martinez, California, on April 20, 2020.Katie Canales/Business Insider

- In March, my roommate and I both got sick — we had headaches, fatigue, coughs, and shortness of breath for two weeks. I even had "COVID toes."

- We figured we both had mild cases of the coronavirus, but never got tested because of testing shortages at the time.

- I got an antibody test this week to find out whether I might now be immune to the coronavirus.

- But my results showed that my antibody counts were under the threshold required to test positive, leaving me with even more questions.

- Here's what the experience was like.

- Visit Business Insider's homepage for more stories.

When the Bay Area issued its shelter-in-place order on March 17, my three roommates and I started preparing to spend the next month together in our small apartment.

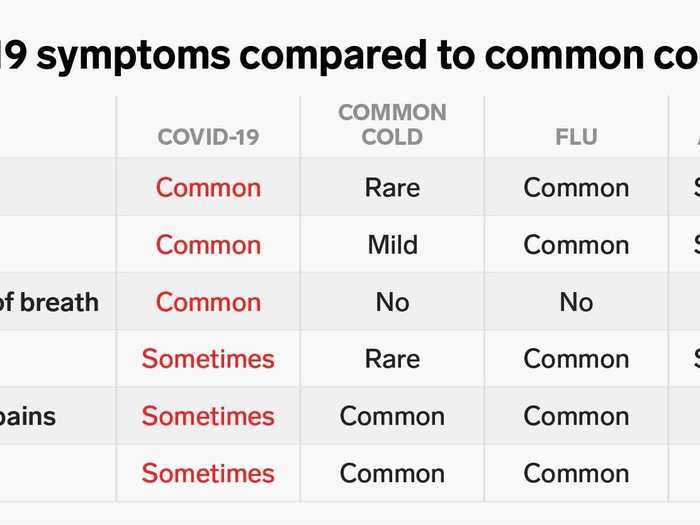

But then two of us started experiencing COVID-19 symptoms: headaches, coughs, fatigue, and shortness of breath. I even had a symptom now deemed "COVID toes" — the middle three toes on both my feet turned deep red and purple, swelling and becoming itchy. (At the time, I didn't realize that was related to my other symptoms, however.)

I called my doctor around day seven of the illness, but she advised against coming in for a test. Because my symptoms didn't require critical medical attention, she said, it wasn't worth going to a medical facility to get tested, since there weren't many available tests and I could risk more potential exposure to the virus.

My roommate and I both self-isolated, recovered at home, and felt almost back to normal about two weeks later.

But we've been left wondering whether the illness we had was COVID-19.

So this week, I took an antibody test, also known as a serological test, which can detect coronavirus-neutralizing antibodies in the bloodstream.

These tests promise answers for the many people like me who experienced coronavirus symptoms but were unable to confirm a diagnosis. They also offer epidemiologists a better sense of the virus' true spread.

But I knew from my own reporting that there are plenty of reasons to be wary. For one, many companies have been offering tests that aren't approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The one I took, from Diazyme Laboratories, Inc., was submitted for FDA authorization but hasn't gotten it yet. In addition, one study found that 6% of recovered coronavirus patients didn't develop antibodies at all, and younger people tended to have lower levels of antibodies than older patients.

I opted for an antibody test anyway, however, hoping to get confirmation that I'd had the virus and am now immune. But my test came back negative, leaving me with even more questions.

Here's what the experience was like.

Read the original article on

Business Insider

I had hoped a serology test would give me clarity about how to move forward.

The reporter at ARCpoint Lab in Martinez, California, on April 20, 2020.

Katie Canales/Business Insider

A positive result would have made me feel more comfortable in public places, allowed me to pursue ways to volunteer to help others, and might even have indicated that I could donate plasma to patients with severe cases.

Instead, I was left with more questions.

Even if my antibody test had come back positive, however, there would still have been questions about my immunity, since scientists aren't sure how long the protection lasts.

The reporter at ARCpoint Lab in Martinez, California, on April 20, 2020.

Katie Canales/Business Insider

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said on April 7 that people who recover from the coronavirus will likely be immune should a second wave of infection spread in the early fall.

"Generally we know with infections like this, that at least for a reasonable period of time, you're gonna have antibodies that are going to be protective," he said.

But because the virus is so new, how long that period of time lasts for recovered COVID-19 patients is still unknown.

I still think my roommate and I probably had the coronavirus, though it's possible we might have gotten another illness.

The reporter at ARCpoint Lab in Martinez, California, on April 20, 2020.

Katie Canales/Business Insider

It's possible that I did get COVID-19, but my immune system cleared the virus without developing many antibodies. The test could also have been inaccurate.

The technician told me I'd receive my results in about 48 hours. A couple days later, they came: I had tested negative.

The reporter at ARCpoint Lab in Martinez, California, on April 20, 2020.

Katie Canales/Business Insider

I was disappointed and confused.

ARCpoint Labs drew a vial of my blood, which would then get sent to an ARCPoint Labs partner lab in Florida, called Access Medical, which has the capability to process the Diazyme Laboratories antibody test.

The reporter at ARCpoint Lab in Martinez, California, on April 20, 2020.

Katie Canales/Business Insider

According to the Diazyme Laboratories website, its coronavirus antibody test detects two kinds of antibodies: IgM and IgG.

The test's accuracy for negative specimens ranges, according to the company: For IgM, its sensitivity is about 90% and specificity is 98%. For IgG, its sensitivity and specificity are 96%.

Sensitivity refers to how many negatives the test catches, and specificity refers to how many samples the test says are positive that are actually negative.

So with IgM antibodies, this test catches about 90% of samples that are negative, but misses about 10%. About 2% of the negatives it gives are false. For IgG, it misses about 4% of negative samples, and 4% of its negatives are false.

These numbers haven't been independently verified, though.

The lab technician told me he's been doing blood tests for years. ARCpoint Labs usually conducts clinical drug and paternity tests.

The reporter at ARCpoint Lab in Martinez, California, on April 20, 2020.

Katie Canales/Business Insider

Still, I'm not very good with needles, so I was nervous about the test.

The form said the results should not be used as the sole basis to diagnose or exclude SARS-CoV-2 (the scientific name of the virus).

A form at ARCpoint Lab in Martinez, California, on April 20, 2020.

Katie Canales/Business Insider

Several recent studies have raised questions about how often coronavirus patients develop antibodies — and whether everyone develops them to a sufficient level to confer immunity. A recent paper (a pre-print that is not yet peer-reviewed) tested recovered patients who had mild coronavirus cases to see how many antibodies they produced.

It found that patients produced differing levels of antibodies, with elderly and middle-aged people developing higher levels of antibodies on average. The researchers also discovered that 10 patients out of the 175 studied — roughly 6% — didn't develop any detectable antibodies at all.

Most of those without detectable levels of antibodies were younger.

I'm 24, so I figured there was a chance that I could have gotten the coronavirus but not developed antibodies to a detectable level.

This week, I drove to ARCpoint Lab's testing facility in Martinez, California. I was the only patient there — the lab staggers appointments to maintain social distancing.

ARCpoint Lab in Martinez, California, on April 20, 2020.

Katie Canales/Business Insider

Once there, I had to sign a consent form indicating that I knew that the test was not FDA-authorized yet and acknowledging some disclaimers about the test's accuracy.

Only three companies and the Mount Sinai Health System have FDA emergency use authorization (EUA) for their antibody tests. Companies without it can still sell their tests to consumers, however, as long as they provide a disclaimer.

ARCpoint Labs in Martinez, California, on April 20, 2020.

Katie Canales/Business Insider

Over 100 companies have applied and are still going through EUA the process. Diazyme Laboratories is one of them.

But even the FDA-authorized tests can be inaccurate, according to reports from the New York Times and others. Cellex, one of the three that are officially authorized, has a false positive rate of around 5%, the Times reported. And a set of serological tests Spain used last month advertised 80% accuracy, but instead were found to be only 30% accurate, according to the Times.

Although I missed my window for a diagnostic test, I knew a serological test could use a few drops of my blood to determine whether I have antibodies for the coronavirus.

The reporter's blood sample at ARCpoint Lab in Martinez, California, on April 20, 2020.

Katie Canales/Business Insider

I asked my doctor if my healthcare provider was offering antibody tests, but they weren't available yet. I also checked the National Institute of Health's open clinical surveys to see if I could volunteer for any trials in my area.

But the easiest option, it turned out, was to go to a local testing franchise facility, ARCpoint Labs, and get an antibody test from Diazyme Laboratories that does not yet have FDA approval.

One morning during my first week working from home, I woke up with a pounding headache, sore throat, and tight chest. Strangely, the middle three toes on both of my feet had turned purple. Something under the skin felt hot and itchy.

Shayanne Gal/Business Insider

My symptoms were relatively mild, but they were still painful and uncomfortable.

My roommate came down with a fever and cough around the same time. Over the next week, our symptoms worsened. My roommate would get out of breath walking up the stairs, and I felt phlegm coming up out of my lungs.

I spoke with my doctor, and she advised against coming in for a diagnostic test, due to limited test availability and the mildness of my symptoms. So I recovered at home and both felt mostly back to normal about two weeks later. It was still harder than normal to breathe for another week or two, though.

I joined Business Insider as a reporting fellow in early January to cover science. In a meeting with the team on my first day, my editor said, "So, we're getting reports about a new virus in China."

The reporter, Holly Secon, at ARCpoint Lab in Martinez, California, on April 20, 2020.

Katie Canales/Business Insider

Soon, I was covering the coronavirus every day. A couple of months later, I wound up living it, too — or so I thought.

I live in the Bay Area, where the first case of community spread in the US was reported at the end of February. That news indicated that there were already hundreds, if not thousands, of cases here.

The virus' spread seems to have started even earlier than that, however. This week, Santa Clara county — which is about an hour away from where I live — found through autopsies that two people who died in their homes on February 6 and 17 tested positive for the coronavirus. (Previously, the US's first coronavirus death was thought to have happened on February 29.)

Gov. Gavin Newsom has asked coroners to review records and conduct autopsies back to December to look for infections.