Here's why the 1930s Great Plains Dust Bowl drought-disaster hit so hard and lasted so long, and why it could happen again

James Pasley

- In the early 20th century, farmers across the Great Plains harnessed new technology to cash in on a huge demand for wheat.

- But over-farming led to the removal of prairie grasses which had kept the topsoil in place.

- For years, the region was bombarded by monster dust storms called "black blizzards" that sometimes buried entire houses in grit.

For almost 10 years, the Great Plains became a desert wasteland.

During the 1930s, after an intensive period of over-farming, dust storms regularly wreaked havoc, blanketing towns and farms in grit, destroying crops and making people sick.

The drought and storms led to one of the largest mass migrations in a short period of time in US history.

When it was over, better farming practices were instituted to ensure it never happened again. But even so, in 2020, new research found that the heat waves which caused the dust bowl were more than twice as likely to occur as in the 1930s.

Here's what it was like and why it could happen again.

It all began with wheat. In the late 19th and early 20th century, thousands of farmers moved to the Great Plains, a stretch of arid land once covered in native grasses that stretched across much of middle America from Texas to Montana.

The farmers were enticed by new federal laws to buy land off developers who had divided massive ranches up for farming.

In the following years, they planted millions of acres of wheat and corn.

Sources: History.com, New York Times, New York Times, Guardian, Texas Highways

Demand for crops, wheat in particular, was high in the 1920s due to World War I. Farmers harnessed new technology like tractors to get the most from their land. At the same time, the weather provided the region with plenty of rain.

Until then, prairie grasses had kept topsoil in place, but with all of the intensive farming and over-ploughing, the soil became less stable.

Sources: History.com, Texas Highways, New York Times

Everything came to a head in the early 1930s when the Great Depression hit alongside a severe drought. Suddenly the demand for wheat had disappeared and the overworked land was ruined.

Sources: History.com, New York Times

Beginning in 1931, massive dust and dirt storms called "black blizzards" or "dusters" monstered the land and the people who lived there.

Sources: History.com, New York Times, PBS

In 1932, fourteen dust storms were reported. By 1933 it was up to 38. The storms rolled through towns "like bowling balls," according to a report by the New York Times.

Sources: New York Times, PBS

When a dust storm hit, day turned to night.

Sources: Washington Post

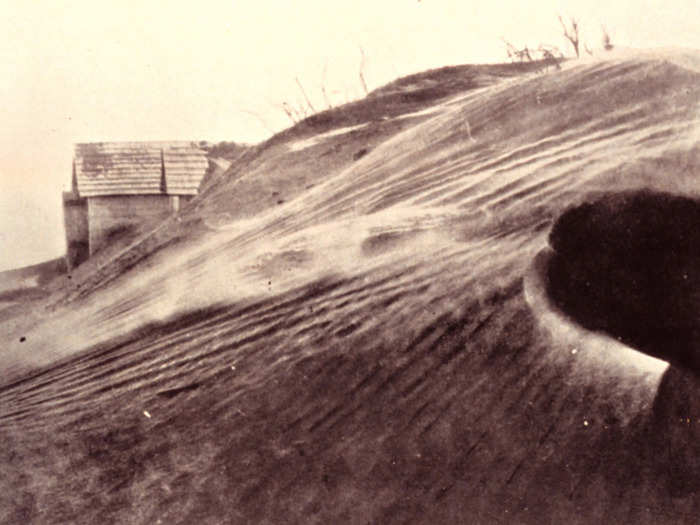

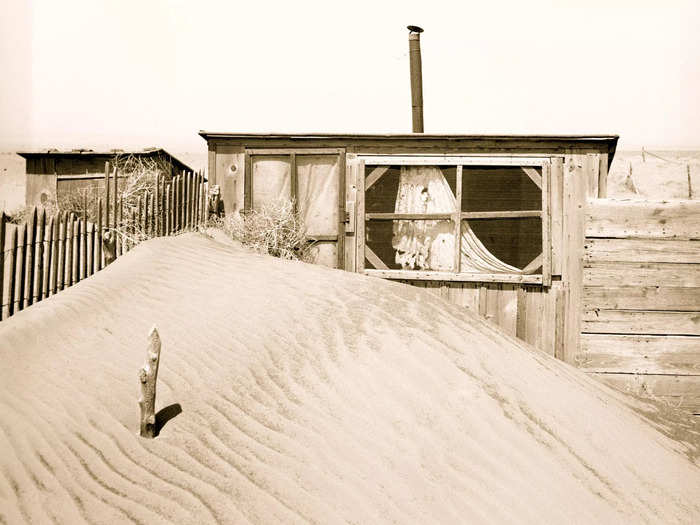

Farms were buried in dust…

Sources: WBUR, YaleEnvironment360

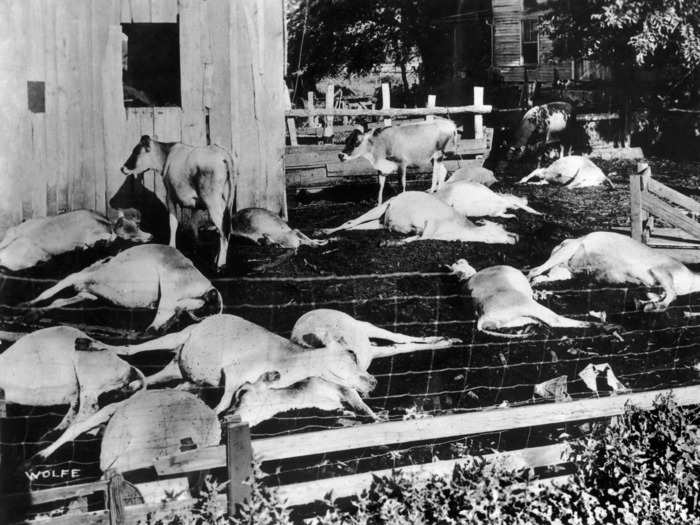

Livestock was killed…

Sources: WBUR, YaleEnvironment360

And farmers were forced into bankruptcy when their prayers for rain went unanswered.

Sources: WBUR, YaleEnvironment360

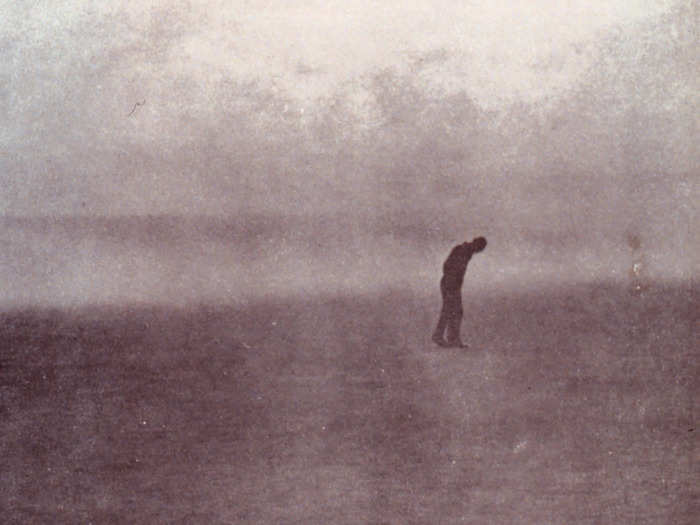

The once beautiful plains became a wasteland.

Sources: WBUR, YaleEnvironment360

Some people tried to carry on as best they could.

Sources: History.com, New York Times, New York Times, Guardian, Texas Highways

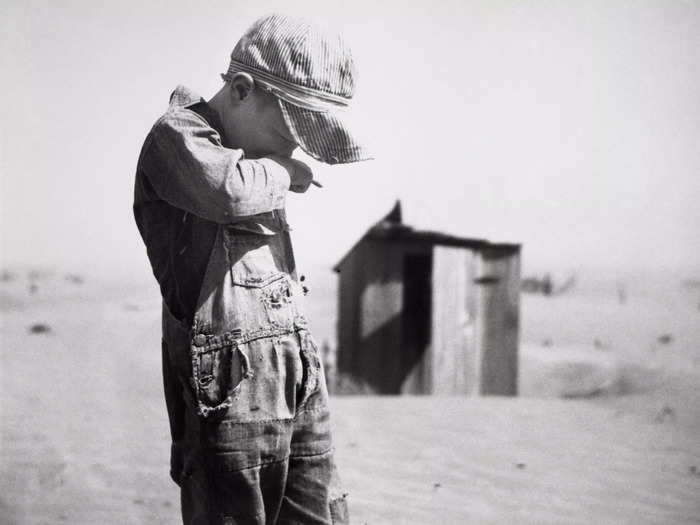

But the dust was toxic. Locals who breathed it in dealt with asthma, influenza, bronchitis and terrible coughs. Hundreds of people ended up dying from the "brown plague," which was basically dust-induced pneumonia.

Sources: History.com

The storms were relentless and appeared, from the ground, inescapable.

As if things weren't bad enough, the period brought masses of grasshoppers and jackrabbits, which finished off much of what remained of the crops.

Sources: History.com

A car full of refugees from the Dust Bowl look for work in San Francisco, California in 1933.

Up to 2.5 million people left the Great Plains, in one of the country's largest ever mass migrations over a short period of time.

But often, things weren't much better wherever they ended up.

About 200,000 people went to California, where they were treated poorly and called "Okies."

Sources: History.com, History.com, CBS News

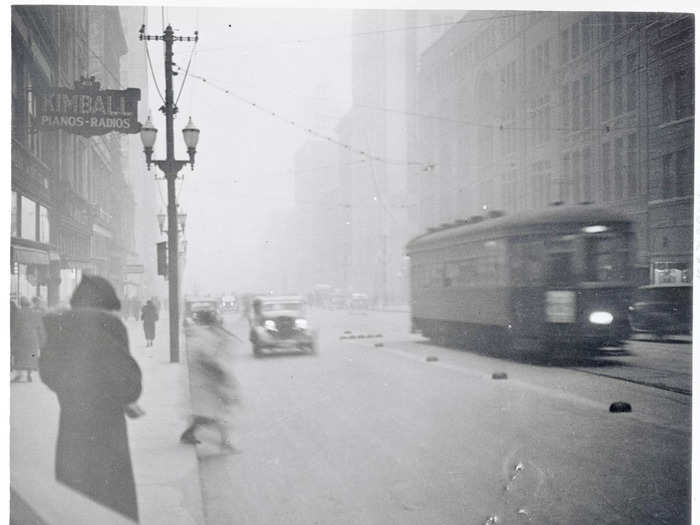

It wasn't just the Great Plains that were struggling. In 1934, more than 75% of the US was hit by a drought. The drought hurt 27 states. Here's Chicago blanketed under a dust cloud several miles long in May of that year.

Sources: PBS

But the Great Plains experienced the worst of it. In 1934 and 1936, the region suffered two of the most intense heatwaves in US history.

In Iowa the temperature hit 118 degrees in 1934, while Oklahoma, Kansas, South Dakota, and North Dakota all hit 120 degrees in 1936.

Climate scientists have found heat and droughts go hand in hand.

University of Brussels climate scientist Wim Thiery told Yale Environment 360, "Dry soils have this exacerbating effect. There is this positive feedback where dry soils lead to more warmth."

If soil is damp then the moisture evaporates under hot sunlight, but when there's no moisture the land heats up easier, meaning more droughts, which in turn means more heatwaves.

Sources: History.com, New York Times, New York Times, Guardian, YaleEnvironment360, Washington Post

Under President Franklin D. Roosevelt the government had been working to help the region during these years.

The government's initiatives included federal aid, limiting banks' ability to evict farmers, relief funds, new employment opportunities, buying cattle off farmers.

It also took over millions of acres of land and converted it into carefully monitored grazing districts.

Sources: New York Times, PBS

But the drought and the storms continued. In 1935, the "Black Sunday" dust storm hit the High Plains. It rolled across the country to cities on the East Coast and the Atlantic Ocean. It is considered the worst storm of the period.

Even locals who had lived through countless dust storms thought it was the end of the world.

Sources: New York Times, YaleEnvironment360

One AP reporter who was trapped in a car overnight after failing to outrun it coined the term "dust bowl." He wrote, "Three little words — achingly familiar on a western farmer's tongue — rule life today in the dust bowl of the continent … 'if it rains.'"

Sources: Time

Black Sunday triggered a national response. Within a fortnight, Congress had called soil erosion "a national menace." It established a new service focused on soil practices, including advocating for rotating crops, terracing, and contour plowing.

Sources: New York Times, PBS

In 1937, the government also launched Shelterbelt Project, a planting project which went for 12 years and cost about $75 million. The aim was to plant up 100 miles of plains between Texas and Canada.

Sources: New York Times, PBS

By 1938, due to all of the work that had been done to the land, air-borne soil was down by 65%. The following year in 1939 it finally rained.

The drought was finally over.

Sources: New York Times, PBS

From then on, farming practices were generally improved. Farmers knew to irrigate their crops so they could handle droughts better.

Sources: New York Times, YaleEnvironment360

And it seemed like the Dust Bowl was a period of US history that no one would ever forget—with iconic photos of the struggle, including this one by Dorothea Lange of Florence Owens Thompson—but that would never be repeated.

Sources: Guardian, CBS News, History.com

Even so, in 2020, new research found—despite all of the improved farming practices—that the heat waves which caused the dust bowl were more than twice as likely to occur as in the 1930s, due to global warming.

Farmers on the Great Plains now rely on water from underground aquifers including the Ogallala Aquifer—one of the world's biggest aquifers—for their irrigation. Up to 46% of irrigated farmland in the area use it.

This aquiver is being overdrawn and some experts have said 70% of it might be used up with the next 50 years.

When the groundwater is depleted a similar period could begin.

Sources: New York Times, YaleEnvironment360, CBS News

US Geological Survey hydrologist Virginia McGuire, who monitors the Ogallala Aquifer, told Yale Environment 360 that water levels in some areas were less than half the size they were 100 years ago.

She said, "If that trend doesn't change, at some point there's going to have to be a reckoning."

Sources: YaleEnvironment360

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement