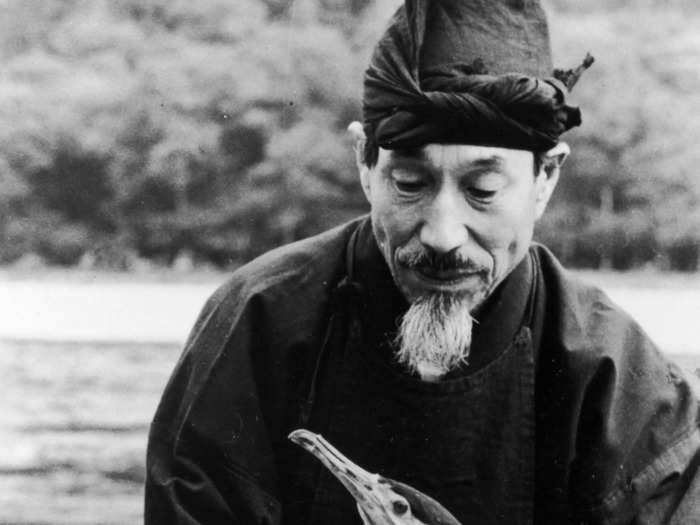

Youichiro Adachi, a cormorant fishing master known as an usho, holds leashes tied to the necks of cormorants as he prepares for cormorant fishing on the Nagara River in Oze, Seki, Japan.KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS

- Cormorant fishing has been a fishing method in Japan and China for over 1,300 years.

- Commercially popular fishing methods put the tradition at risk of disappearing.

Under the light of the moon, with sparkling fire swinging from the edge of their boats lighting their way, Gifu City's fishermen are ready to start their day.

Instead of using poles, rods, and lures, the fishermen, known as an usho, use cormorants to retrieve the ayu sweetfish from the river, in an ancient practice known as ukai.

The fishermen are responsible for a team of 10 cormorants raised from hatchlings. They tie ropes around their necks to maintain control of them and prevent them from swallowing any big fish.

But as the climate changes, the practice faces a new set of problems. Increasing sediment on the riverbeds, heavier rains, and man-made flood barriers disrupt the ayu's natural habitats and food sources.

Cormorant fishing was once common in Japan, and a similar method was practiced in early China.

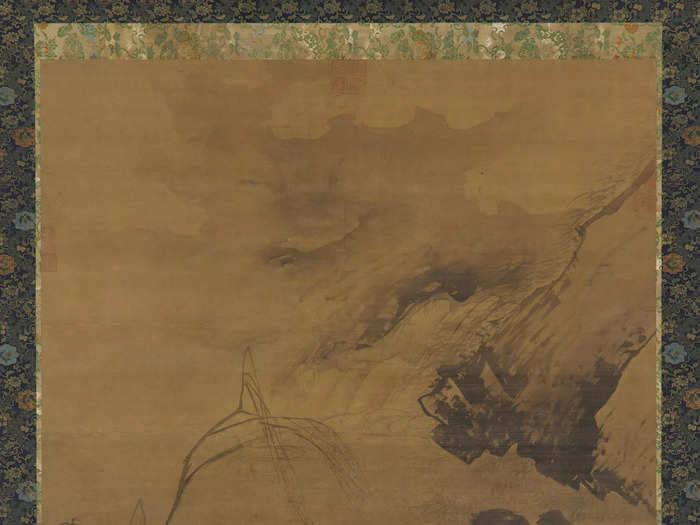

A 16th-century image depicting fishing with Cormorants from the Ming dynasty. Heritage Images via Getty Images

Once a flourishing and popular practice, ukai has been in decline for decades as more commercially successful practices dominate the market and leave little need for the usho.

Nowadays, most usho in Gifu City in Japan make most of their money from tourism. Tour boats pass by to watch the usho catch fish that they'll later eat as part of their tour.

The practice even gained popularity amongst European aristocracy.

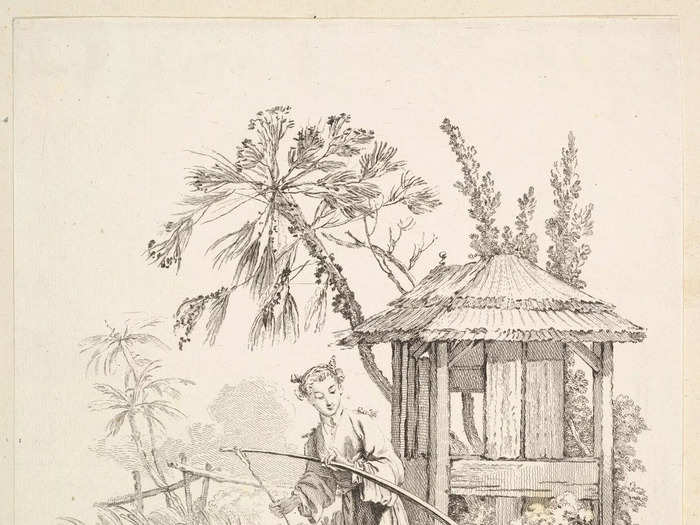

A 16th-century engraving by French artists of a woman and child fishing with cormorants. Sepia Times via Getty Images

During the 16th and 17th centuries, British and French kings practiced cormorant fishing as a leisure activity.

King James I was known to own cormorants and use them in this manner. There are records that King James I introduced cormorant fishing to other European aristocrats by sending them cormorants as gifts.

The practice of cormorant fishing hasn't changed much.

A group of usho sit on the beach watching their cormorants stand on their baskets. Keystone-France via Getty Images

Current usho are amongst the 17th or 18th generation to practice cormorant fishing.

They raise and train their cormorants from hatchlings and follow the same tradition as their parents before them.

The fishing season lasts from May to October, and most usho begin fishing at sundown.

Cormorant fishing master Youichiro Adachi, and his son Toichiro, anchor their boat to a fishing spot on Nagara River. KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS

The ayu that usho and their cormorants fish for are most active at night.

Cormorants are put on the boats in large bamboo baskets and taken to the river to begin their day.

A cormorant belonging to the cormorant fishing master, or usho, Youichiro Adachi, sits in a basket before cormorant fishing. KIM KYUNG-HOON/ REUTERS

Once on the river, Usho light fires over the water to attract fish and help their cormorants see.

A cormorant swims to catch ayu river fish. KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS

Once the cormorants are in the water, their instincts kick in, and they chase after all the fish scattered throughout the riverbeds.

Usho tie loose knots around the necks of the cormorants to control them and prevent them from swallowing big fish.

A man holds onto the strings that are attached to each cormorant's neck. REUTERS/Issei Kato

The cormorants have been trained since hatchlings to catch fish and return to the boat, where the usho will massage their neck to get the fish back out.

Cormorants can keep track of how many fish they catch and, if they aren't rewarded with fish for themselves, will stop diving for more fish.

Ayu with beak marks from cormorants are usually worth more.

A fish with marks of a cormorant on its body. KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS

Usho have an imperial mandate to send ayu that they catch with their cormorants to the imperial household.

The mandate originates from Samurai Warlord Oda Nobunaga, who was fond of the ayu and worked to protect the tradition, being the first to give the cormorant fisherman the title usho.

But the fish that the cormorants are catching are getting smaller and harder to find.

Ayu river fish heads are unfolded to extract the sensory bones, next to 20-year-old samples taken by members of Gifu Prefectural Research Institute for Fisheries and Aquatic Environments. KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS

The major contributing factor to these changes is climate change.

An usho sits in his hut during a sudden rain shower on the river. KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS

Local usho attribute the changes to unpredictable weather. Heavier rains and floods on what was once a calm river have started to disrupt the ecosystem.

Researchers recognized the impact of climate change on local ecosystems.

Gifu University professors collect water to analyze the environmental DNA of ayu river fish from the Nagara River. KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS

Because of the increased temperatures of the river, reaching a high of 86 degrees Fahrenheit, ayu spawn a month later than usual.

Flood barriers built in response to heavier rains reduce the amount of large rocks flowing into the river bed. The rocks are key to growing algae, which the ayu feed on. With fewer large stones, the ayu has dwindling access to a key food source.

The larger rocks also form a habitat for the ayu, and with smaller rocks and sand in the riverbed, the ayu have fewer places to breed, eat, and live.

As the fish are in decline and the tradition is fading, ukai is now mostly supported through tourism.

Maiko Kikuyu, serves visitors on a viewing boat during a party organized by the nonprofit organization ORGAN, before watching cormorant fishing. KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS

In some cities, boats allow visitors to eat and drink while they watch the usho work.

In Gifu City, one of the most popular cities for cormorant fishing, the spectacle draws in over 100,000 people a year and brings in approximately $2.5 million USD a year.

But climate change has also posed a threat to the tourism business.

Houkan (male counterpart to Geisha) Tatsuji, and Maiko (apprentice female Geisha), Kikuyu, sit with visitors to watch cormorant fishing at a riverside observation deck. KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS

The same environmental factors that impact the ayu have carried boats off course or canceled tours at the last minute.

Recently, an economic development body known as ORGAN set up elevated riverside viewing decks on a trial basis. The decks are an attempt to recreate the boat experience and are even hosted by apprentice geishas and other traditional performers.

As the climate continues to change and industrial fishing increases, the future of ukai is uncertain.

A cormorant fishing master sits near a bonfire before cormorant fishing for the night. KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS

With the job being less lucrative, younger generations are faced with a difficult choice.

Toichiro, son of cormorant fishing master, Youichiro Adachi, works as a programmer at a Nagase Integrex factory in Seki, Japan. KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS

Toichiro Adachi, the son of the usho, Youichiro Adachi, is training to become a cormorant master but spends his days working computers making high-precision machine tools.

They can either choose an industry job or continue the centuries-old family tradition.

Toichiro (right), stands on a boat with his father, Youichiro Adachi, after cormorant fishing on the Nagara River in Oze, Seki, Japan. KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS

"I want my son to inherit my job, but it's tough to make a living," Adachi told Reuters. "If we cannot catch fish anymore, our motivation is gone and there's no meaning in what we do."

Not only is the loss of tradition at risk, but the bond between the usho and their birds.

A seventeenth-generation Japanese Master of Cormorants stands with one of his birds by the Nagara River in Gibu, Japan circa 1950. Three Lions via Getty Images

The bond between usho and their cormorants is so strong that their birds will only listen to them.

Youichiro Adachi strokes his bird's neck during a daily physical check-up to confirm its health and maintain their bond. KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS

"For me, cormorants are my partners," Adachi told Reuters.

Usho and their cormorants don't just work together — the two spend their whole lives together.

Cormorant fishing master, Youichiro Adachi, imitates the fluttering of a cormorant to make the bird mimic him, giving Adachi a chance to check on its health. KIM KYUNG-HOON/REUTERS

Cormorants in the wild live for 10 years, but cormorants under the care of their usho can live for up to 30.

When a cormorant dies of old age, it is ceremonially cremated. At the closing of each fishing season, all the usho hold a vigil presided over by a Buddhist priest to honor all the cormorants that passed away that year.

"They are essentially members of my family," Shuji Sugiyama told the South China Morning Post. "I am constantly checking on their health and making sure they're rested and well-fed. I don't see myself as their master; I am part of their team."