Aristotle first spotted 'blood snow' on Mount Olympus. Today, photos show that colorful algae may be eating away Earth's glaciers.

Morgan McFall-Johnsen

Blooms of colorful algae on glaciers in the Alps, Antarctica, and Greenland.Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images; Dr. Matt Davey; Rey Mourot

- Photos show colorful algae blooms are turning glaciers pink, purple, and green across the planet.

- Aristotle first wrote about "blood snow." The glacier algae is probably a vestige of the Ice Age.

You might think of glaciers as vast fields of white snow. But some of them are changing colors.

Pink snow at the Presena glacier, near Pellizzano in the Italian Alps. Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images

In Greenland, glaciers are turning a deep purple-grey — almost black.

A drone image shows researchers trekking to a vast bloom of purple algae staining the Greenland ice sheet black. Courtesy of Laura Halbach

In Antarctica, they're peppered with green snow.

Scientist Andrew Gray surveys blooms of green snow in Antarctica. Dr. Matt Davey

And in the Alps, they're blushing pink.

A man walks on pink snow at the Presena glacier near Pellizzano, Italy. Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images

In all these places, and more, the culprit is microscopic algae.

Purple algae from Greenland, imaged through a microscope. Courtesy of Katie Sipes

Colorful blooms of snow and ice algae have been documented on glaciers in nearly every continent.

A strip of "blood snow" filled with red algae cuts across a dark bloom of purple algae in Greenland. Dr. Pamela E. Rossel/GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Potsdam

The first written record of a glacier algae bloom comes from the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. He wrote about seeing pink snow on Mount Olympus.

Illustration of a sculptural bust of Greek philosopher & teacher Aristotle (384 - 322 BC) Stock Montage/Getty Images

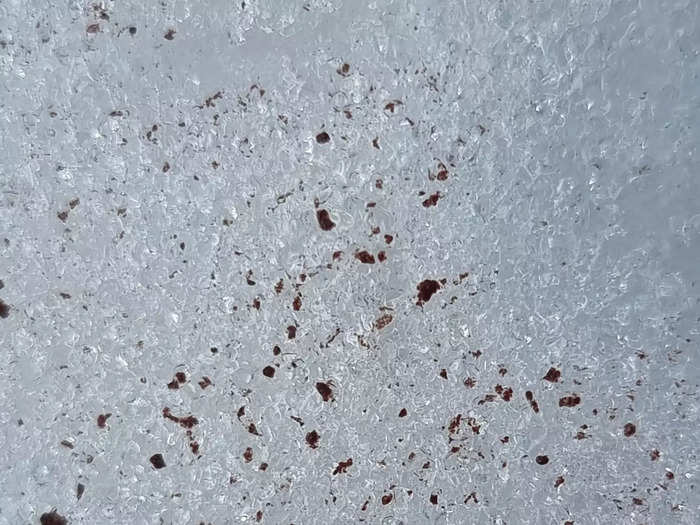

Today, people call that "blood snow" or "watermelon snow."

Eric Maréchal/AlpAlga

Researcher Eric Maréchal suspects snow and ice algae are on every glacier on Earth — vestige of a time when ice covered the planet, 20,000 years ago.

Eric Maréchal shows a sample of microalgae near the Galibier peak, in the French Alps, on June 18, 2021. Philippe Desmazes/AFP/Getty Images

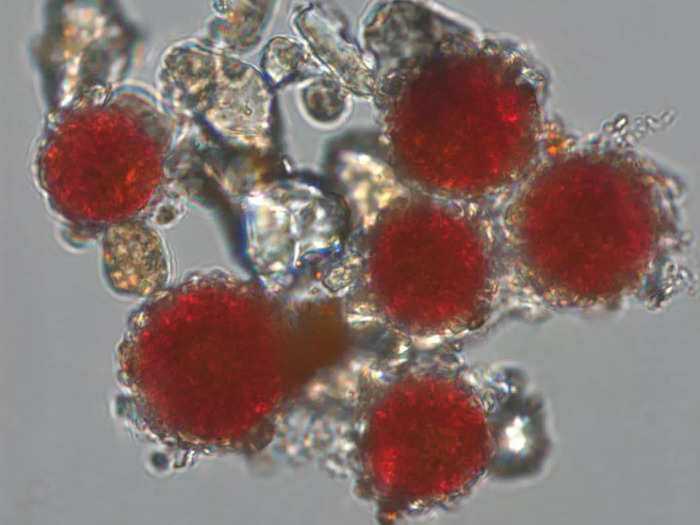

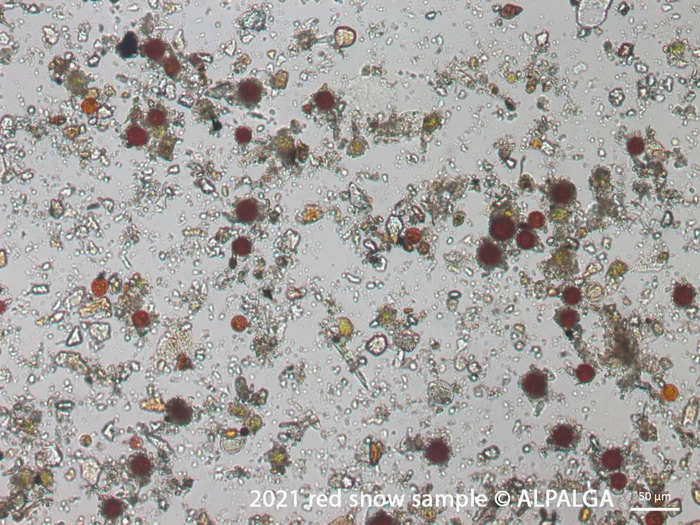

Maréchal studies the red algae that makes blood snow. He leads a research group called AlpAlga.

The algae that makes "blood snow," under a microscope. Eric Maréchal/AlpAlga

He's one of many scientists who think the algae blooms are getting bigger and more common — both an indicator and a driver of glaciers' catastrophic disappearance.

A researcher takes a sample of Sanguina nivaloides algae at the Brevent in Chamonix, France, June 14, 2022. Denis Balibouse/Reuters

That's because microalgae thrive in warmth and moisture.

Eric Maréchal/AlpAlga

"The moment you have melting, the algae just are happy," Liane G. Benning, who studies purple ice algae in Greenland, told Insider.

Liane G. Benning examines an ice core in Greenland. Courtesy of Katie Sipes

"They just need a little bit of water," she added. "And they have a party. They go and bloom."

A helicopter flies above a purple algae bloom darkening the ice sheet in Greenland. Dr. Pamela E. Rossel/GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Potsdam

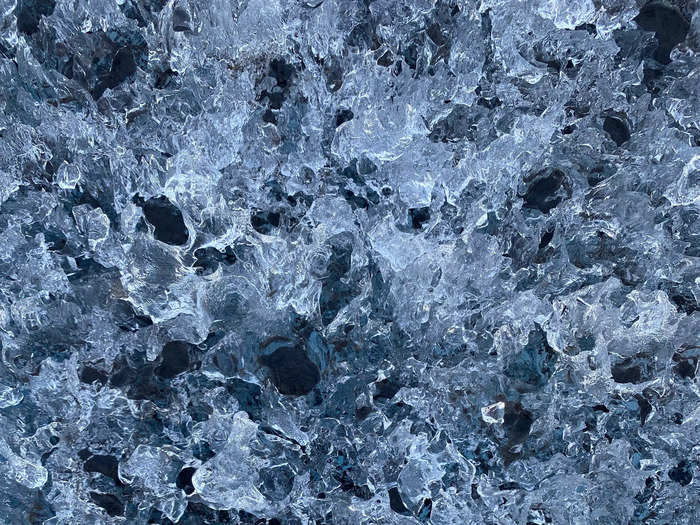

While the algae are partying, they're slowly killing their hosts. Instead of the blinding white that reflects sunlight away from a glacier, algae blooms create vast patches of pink, red, purple, or green.

A close-up of wet ice full of algae. This image is about 20 centimeters wide. Courtesy of Rey Mourot

Studies in the Himalayas, Greenland, Alaska, and across the Arctic have found that these colorful blooms cause glaciers to absorb more sunlight, leading to new ice melt.

Annotated image of snow fading into darkened ice in Greenland. Insider/Laura Halbach

This could have dire consequences. Glacier melt is raising sea levels, driving extreme weather, and diminishing water supplies worldwide.

Rising sea levels destroy homes built on the shoreline, forcing villagers to relocate, in El Bosque, Mexico, November 7, 2022. Gustavo Graf/Reuters

But the idea that the blooms are getting bigger is still a hypothesis, since there's no thorough record of glacier algae before human-caused climate change.

A DeepPurple research camp in Greenland, surrounded by an algae bloom, as seen from a drone. Courtesy of Rey Mourot

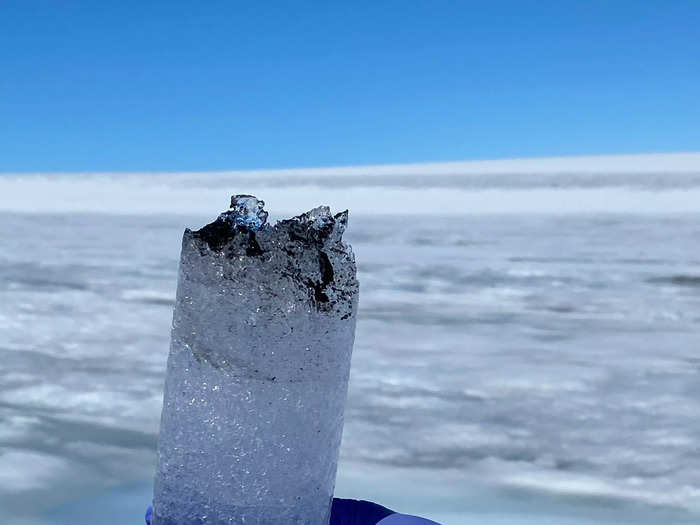

Benning's research group, Deep Purple, is trying to fill this gap.

Deep Purple researchers store samples in Greenland. Courtesy of Laura Halbach and Alex Anesio

They're looking back in time by drilling into the ice, where they hope to find clues about the history of algae on the Greenland ice sheet.

Liane G Benning

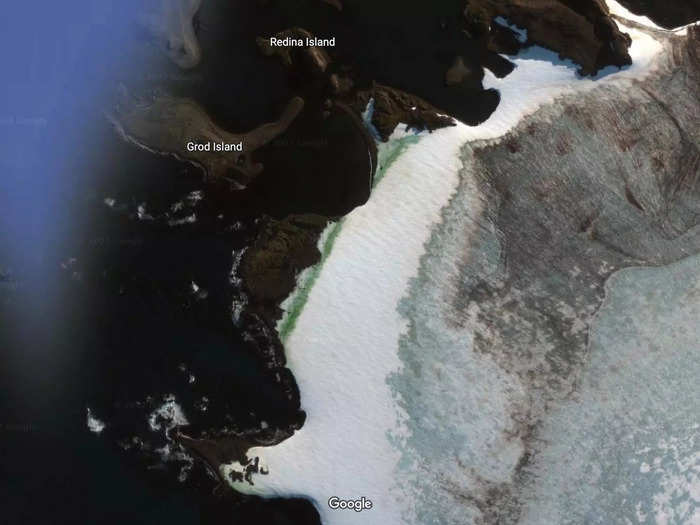

Researchers like Andrew Gray are also using satellite imagery and drones to measure today's algae blooms.

Satellite imagery shows green blooms of algae lining the coast of Robert Island in Antarctica. Landsat/Copernicus/Maxar Technologies/Google Maps

"We still don't know much about the fundamental ecology of snow algae," Gray, who studies green snow algae in Antarctica, told Insider in an email.

Multi-colored snow algae on Anchorage Island in Antarctica. Dr. Matt Davey

He's trying to solve some key mysteries about the algae: "where they are, why they are where they are, and how they're likely to respond to warming."

Researcher Matt Davey samples snow algae at Lagoon Island, Antarctica. Sarah Vincent

For Maréchal, warming is actually making it harder to study the algae.

Sunset over the Mediterranean, as seen from Mount Olympus. Eric Maréchal/AlpAlga

In May, his team hiked to the glaciers to take samples of snow while it was still white. They needed a baseline to compare against later in the summer, once the red algae started blooming.

Maréchal's colleagues, Stephane Ravanel and Lucie Liger, take samples of red snow algae on Mount Olympus. Eric Maréchal/AlpAlga

But when they reached their sampling site on Mont Brevent, expecting blankets of pure white snow, they found it was already pink with algae.

Eric Maréchal searches for Sanguina nivaloides algae at the Brevent in Chamonix, France. Denis Balibouse/Reuters

When they returned a week later, all they found was bare earth. The snow had already melted away.

A research site atop Mont Brévent, usually covered in seasonal snow through early July, lost most of its snowpack in May. Eric Maréchal/AlpAlga

One Italian ski resort covered a glacier with reflective white material to counteract the snow's color change and slow its melt. But that's not an option in most places.

Huge geotextile sheets on the Presena glacier near Pellizzano in Trentino, northern Italy, in order to delay snow melting on skiing slopes. Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images

"What can we do about these pesky algae? Everybody asks that question," Benning said. "We should bloody stop changing the climate."

A coal-fired electricity plant in Juliette, Georgia. Chris Aluka Berry/Reuters

The scientists don't think their algae research will solve the problem. But it can help inform better models of future glacier melt. For now, modeling doesn't account for algae.

Courtesy of Laura Halbach and Alex Anesio

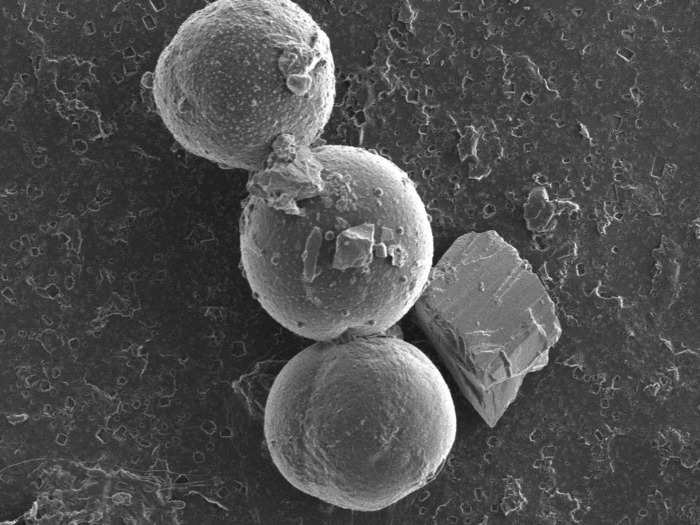

"My perception of life in Antarctica really changed when I started thinking of the snow and ice as a kind of soil, supporting all sorts of bacteria, fungi, virus, cyanobacteria, algae (of course), all the way to invertebrate life," Gray said.

Red snow algae under an electron microscope. Liane G Benning/German Research Centre for Geosciences/GFZ Potsdam

"Most people when they go on a glacier and they look at that, they think it's just dirt," Benning said.

Researchers stand in a vast patch of glacier darkened by purple algae in Greenland. Courtesy of Laura Halbach and Alex Anesio

Generally, studying microalgae in the snow and ice can help researchers understand Earth's glaciers and the hidden worlds inside them, before they disappear.

An AlpAlga researcher digs beneath a pink algae bloom. Eric Maréchal/AlpAlga

But like dirt, the ice has a life of its own. And it may be changing with the climate, just like life everywhere else.

Courtesy of Laura Halbach and Alex Anesio

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement