16 plutonium-powered space missions shaping our understanding of space — including the NASA rover that will search for alien life on Mars

Dave Mosher

- NASA last week launched its Mars 2020 Perseverance rover to hunt for signs of ancient alien life.

- Once on Mars, Perseverance will be powered by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator. The nuclear "battery" is fueled by a rare human-made material called plutonium-238.

- Perseverance is just the latest in a long line of groundbreaking, plutonium-powered spacecraft that have changed our understanding of the solar system.

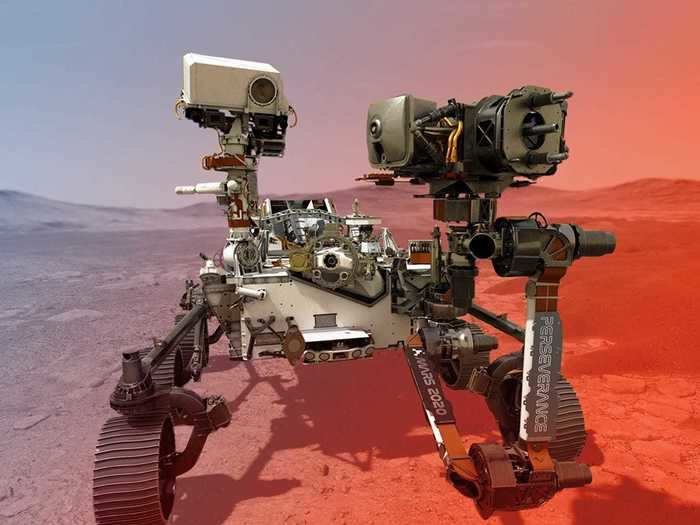

NASA's latest car-size Mars rover, Perseverance, rocketed off Earth last week, kicking off a seven-month voyage through deep space to Mars.

The robot is designed to spend three years exploring the red planet's surface, hunting for signatures of ancient alien microbes, stashing Martian soil samples for future return to Earth, deploying the first-ever interplanetary helicopter, and paving the way for human explorers with a variety of experiments.

However, a device called a multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator, or MMRTG, could power Perseverance for more than 14 years thanks to a unique nuclear material called plutonium-238, or Pu-238. The material has powered NASA spacecraft for decades, including some for close to half a century.

Pu-238 is a byproduct of nuclear weapons production. Unlike its sister chemical, plutonium-239 (which makes up the fissile cores of bombs), half of any amount decays within about 87 years. On a spacecraft, Pu-238's decay gives off lasting warmth that helps safeguard fragile electronics. Most importantly, wrapping Pu-238 with thermoelectric materials that convert heat to electricity, forms a bewilderingly long-lasting power source.

The space agency used to have just only 37 lbs of Pu-238 left to put inside a spacecraft — enough for another two or three spacecraft.

But NASA and the US Energy Department have resurrected Pu-238 production capabilities, helping provide enough material for Perseverance and future missions.

To tide you over until the Perseverance reaches Mars and begins its alien hunt, here are the 16 greatest Pu-238-powered US space programs of the past and present — plus more that have yet to launch.

Transit satellite network

Physicist Glenn Seaborg discovered plutonium in 1940. Just 20 years later, engineers used it to build nuclear batteries for spacecraft.

In 1960 the US Navy took over an experimental plutonium-powered satellite program called TRANSIT to guide their submarines and missiles from space.

The first satellite powered by plutonium, called Transit 4A (above), reached orbit on June 29, 1961.

Slide Embed

By 1988, dozens of similar spacecraft — four of them using nuclear power sources — made up a rudimentary satellite navigation network.

Each satellite beamed a unique radio signal. With multiple signals coming from different orbits, the Navy could easily track its submarines and other wartime hardware.

But space scientists hit a snag early on: Their data suggested that spacecraft slowed down or sped up over certain parts of Earth.

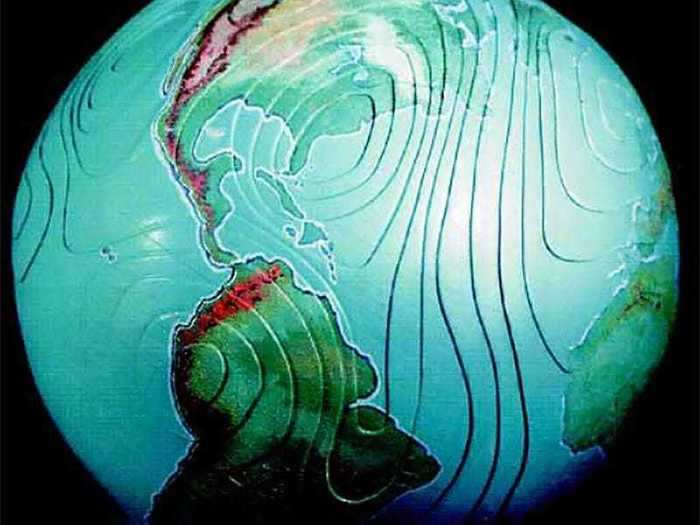

transit satellite navigation map

When researchers mapped the anomalies, they realized that some regions of the planet were far denser than they thought, and that the extra mass — and gravity — subtly affected spacecraft speed.

The map of the anomalies (above) became the first of Earth's geoid, a representation of the planet's true gravitational shape. It's now essential to correcting the orbits of satellites.

Apollo surface experiments

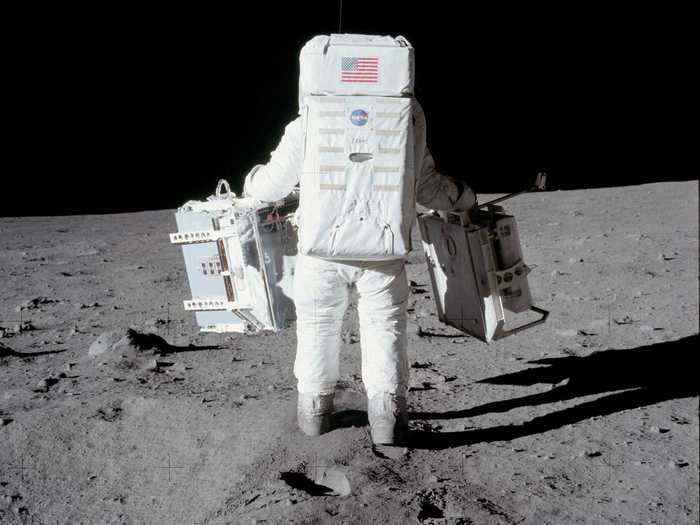

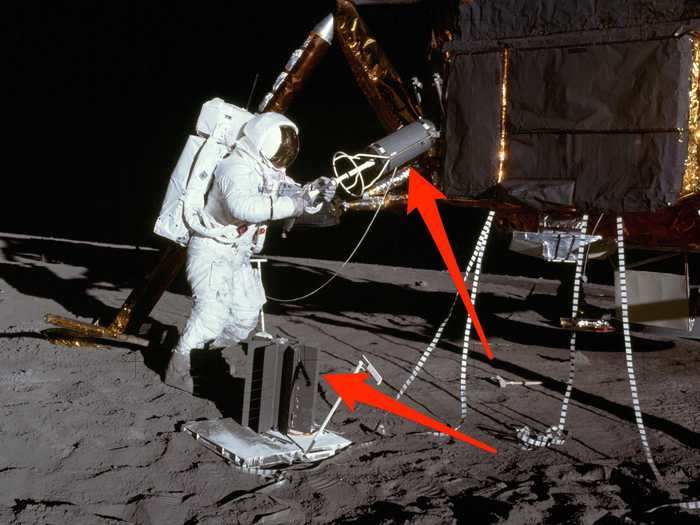

Apollo 11 astronauts in July 1969 dropped off about 1.2 ounces of Pu-238 on the moon.

The material sat inside a device called the Apollo Lunar Radioisotopic Heater. The device kept a seismic monitoring station warm during half-month-long lunar nights, when surface temperatures can dip to to -243 degrees Fahrenheit (-153 degrees Celsius).

apollo surface experiments pu 238 fuel

All subsequent Apollo missions used plutonium, but kept theirs inside of nuclear batteries to provide 70 watts of power. That's on par with an incandescent light bulb's energy use — and just enough to charge the electronics of surface experiments.

Above, astronaut Alan Bean pulls a plutonium fuel cask from the lunar lander during Apollo 12's first extravehicular excursion.

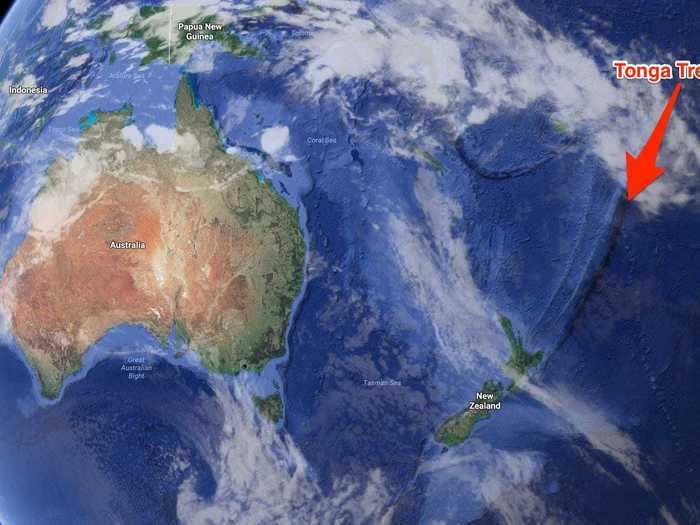

tonga trench google maps apollo 13

A similar nuclear battery from NASA's flubbed Apollo 13 mission survived reentry to Earth orbit. NASA suspects it landed somewhere in the bottom of the Tonga Trench in the South Pacific Ocean.

To this day, no one has found it, or detected any release of the material.

Nimbus B-1 satellite

One of the most important space missions powered by Pu-238 began with a disaster.

The Nimbus-B-1 satellite was supposed to use its nuclear battery to measure Earth's surface temperatures from space, through both day and night.

But when it launched on May 18, 1968, a booster failed and mission control blew up the rocket and spread chunks of spacecraft all over the Pacific Ocean.

nimbus b1 satellite fuel casks nasa

All was not lost, though.

A crew recovered the battery's fully intact fuel casks (above) between California's Jalama Beach and San Miguel Island, demonstrating their robust safety design.

Nuclear engineers recycled the plutonium fuel into a new battery, which was used in the follow-up Nimbus III mission (one of the very first navigation satellites to aid search-and-rescue operations).

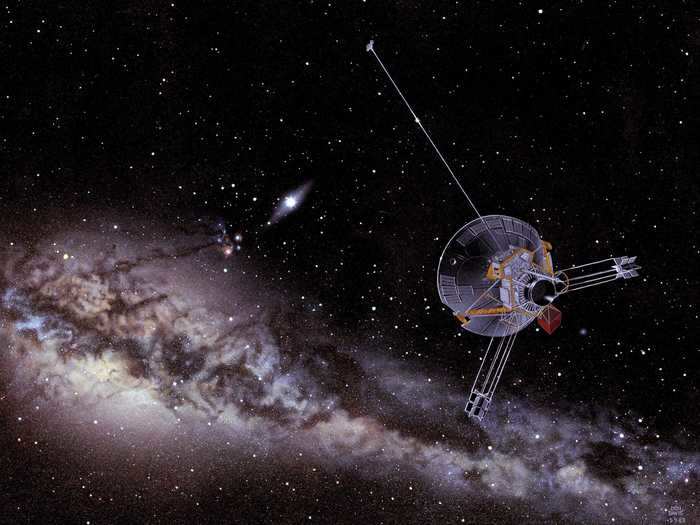

The Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 probes

NASA intended its Pioneer program of more than a dozen spacecraft to explore the moon, visit Venus, and monitor space weather.

But most people remember Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 for their daring flybys of never-before-visited outer planets.

jupiter pioneer 10 photo nasa flickr 7544560948_f61c3a88e7_o

Pioneer 10 launched on March 2, 1972. NASA maintained contact with it until 2003, when, at a distance of 7.5 billion miles (12 billion kilometers), its radio signal became too weak to detect.

Using a 155-watt nuclear battery, it became the first spacecraft to cross the Asteroid Belt, visit Jupiter, and beam back images of the gas giant.

pioneer 11 saturn photo nasa

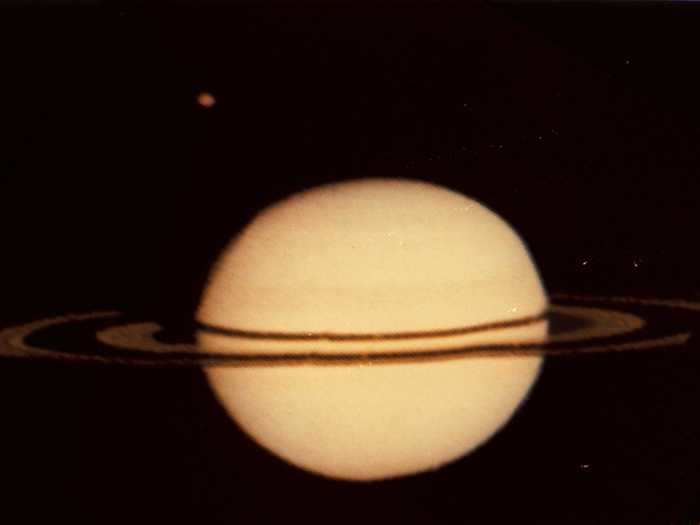

Pioneer 11, which launched on April 6, 1973, became the first spacecraft to visit Saturn. NASA lost contact with that probe more than 22 years after its launch, when it was billions of miles from Earth.

Pioneer 10 lasted significantly longer, launching on March 2, 1972, and sending its last, feebly detectable signal on April 27, 2002 — more than three decades of continuous operation.

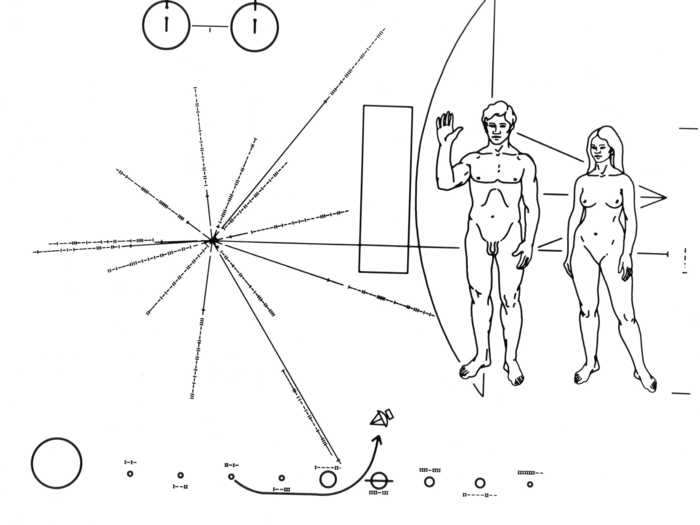

pioneer spacecraft plaque nasa 9457918847_9b5ba200fb_o

Just in case the probes bump into intelligent aliens, each one carries a plaque to communicate basic information about the spacecraft's origin and creators.

The Viking landers

By the time sunlight reaches Mars, it's about 50% less intense than on Earth. Combined with a dusty and windblown environment, solar panels become a liability for surface spacecraft.

To touch down on the Martian surface for the first time in 1976, NASA built two Viking orbiters and a Pu-238-powered lander for each one.

Both landers carried stereoscopic cameras, a weather station, a shovel, and a soil-sampling chamber to sniff out signs of life 140 million miles (225 million kilometers) from Earth.

viking 2 lander panorama 2 vandencbulek nasa

Neither lander dug deep enough to find water ice, and the soil experiment failed to detect organic molecules, though they did sniff out carbon dioxide — a gas emitted by most active lifeforms — when it introduced a nutrient-rich liquid to the soil.

Although non-biological soil chemistry likely caused the anomalous result, the Viking landers didn't labor in vain.

In addition to returning stunning views of the red planet (above), the landers made the case for NASA to send a flotilla of spacecraft to visit Mars, including the Phoenix lander, which found both water ice and the chemicals that may have tricked Viking's life-detecting experiments.

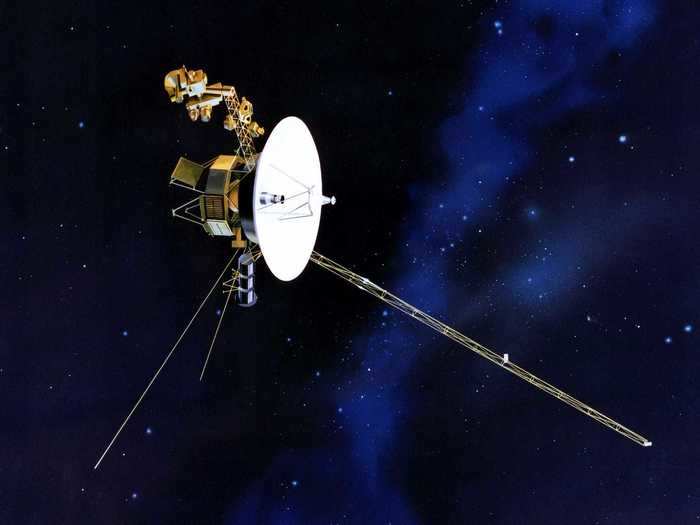

The Voyager probes

The Voyager probes, launched in 1977, capitalized on years of improvements in electronics over their predecessors, Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11, to return stunning views of the solar system — including a view of the Earth from 4 billion miles away that Carl Sagan championed.

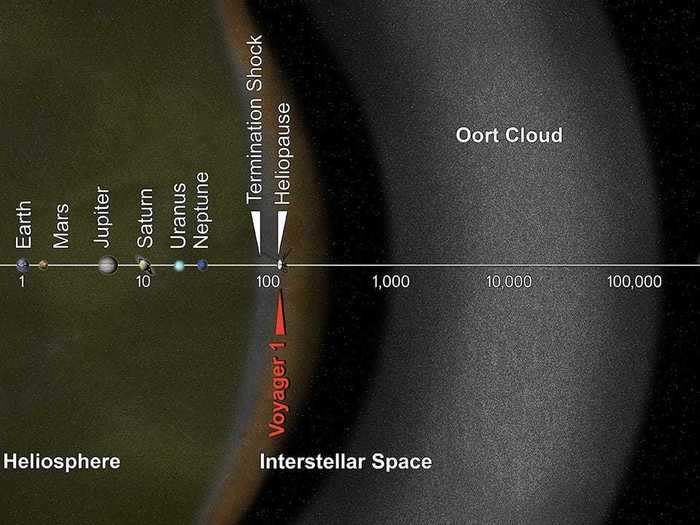

voyager 1 spacecraft location left solar system heliosheath nasa jpl pia17046red full

At 13.9 billion miles (22.4 billion kilometers) and counting, Voyager 1 is the farthest human-made object from Earth.

It left the planetary solar system and reached the interstellar medium, or space between star systems, in August 2012.

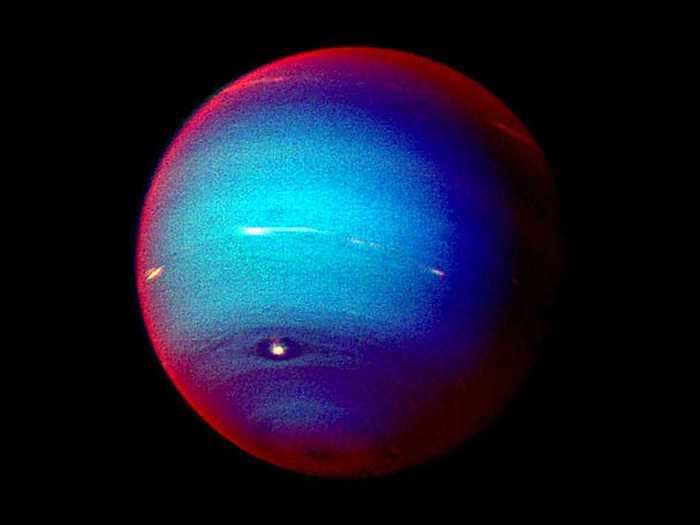

neptune voyager false color

Despite the vast distances and more than 40 years of operation, each of the Voyagers' three Pu-238-filled nuclear batteries allow the spacecraft to continue communicating with ground stations on Earth.

NASA expects each spacecraft to go fully offline by 2025.

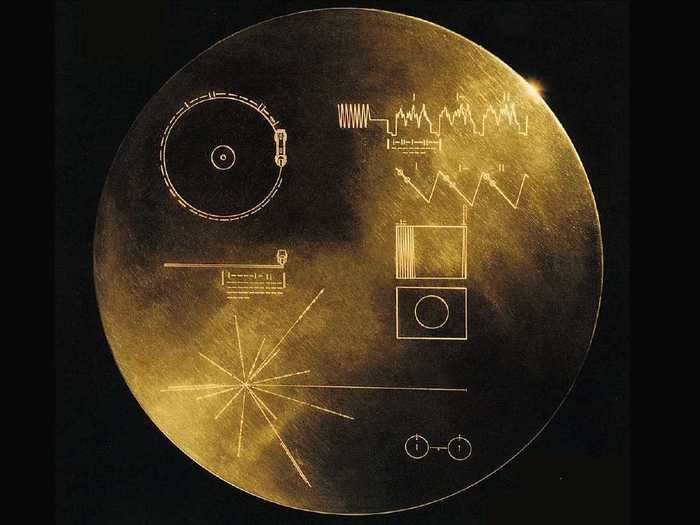

voyager golden record

Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 also launched with a more advanced message for any intelligent life they encountered: a golden record full of images, audio and other information about Earth and its lifeforms. This time capsule of humanity is expected to last about 1 billion years.

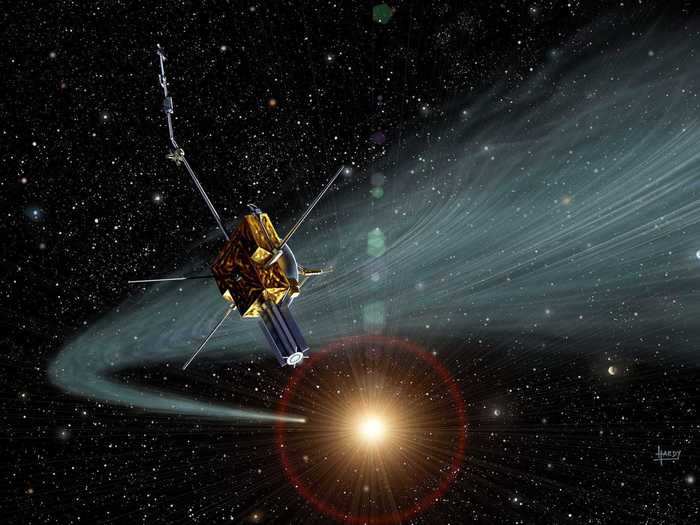

Ulysses solar orbiter

To get into a peculiar orbit above and below the sun to study its poles, designers of the Ulysses spacecraft ran into a paradox: a sun-probing machine that couldn't rely on solar power.

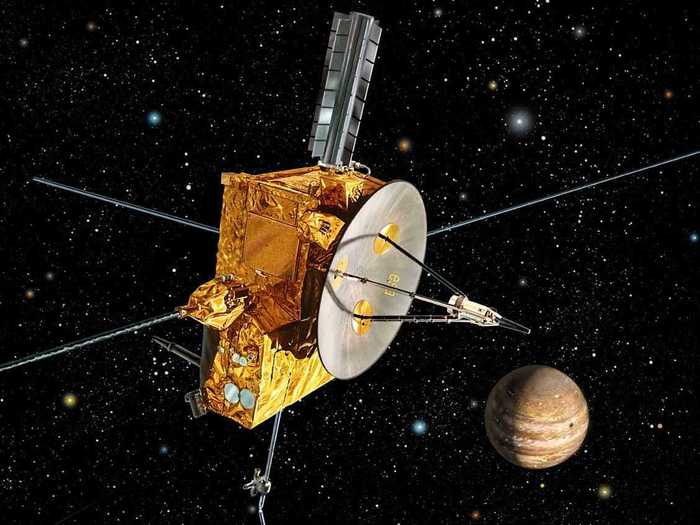

ulysses spacecraft jupiter flyby illustration nasa esa PIA18173

Achieving Ulysses' orbit required flying to Jupiter, then using the gas giant's gravity to slingshot the spacecraft into a proper trajectory.

Sunlight is 25 times dimmer at Jupiter than at Earth, and solar panels would have doubled the spacecraft's weight — 2,500 lbs (1,130 kg) of arrays versus a 124-lb (56-kg) nuclear battery.

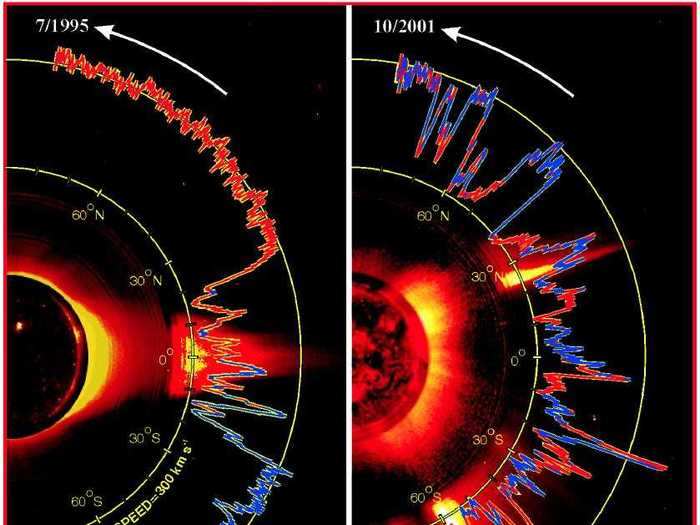

ulysses solar wind chart nasa

Ulysses launched in 1990, pulled off the Jupiter gravity assist two years later, and began its mission in 1994.

It lasted until 2009, when the decaying Pu-238's warmth faded enough that it couldn't keep Ulysses' hydrazine propellant from freezing.

Before it perished after nearly 19 years of service, however, Ulysses flew through the tails of several comets, explored the sun's north and south poles, and probed the solar wind.

Galileo Jupiter probe

Launched from the payload bay of space shuttle Atlantis in 1995, the Galileo probe used two nuclear batteries to give it 570 watts of power.

galilean moons jupiter io europa ganymede callisto nasa jpl dlr

About enough to run a dorm room microwave, that initial output allowed Galileo to study Jupiter and its four large moons Io, Callisto, Ganymede and Europa.

galileo jupiter illustration nasa.JPG

Space scientists operated Galileo for 14 years, eight of them spent around Jupiter.

To safeguard potentially life-supporting Jovian moons from any stray Earthly bacteria stuck to the spacecraft, NASA plunged it into Jupiter's thick atmosphere at about 100,000 mph (161,ooo kph) in 2003.

Cassini Saturn probe

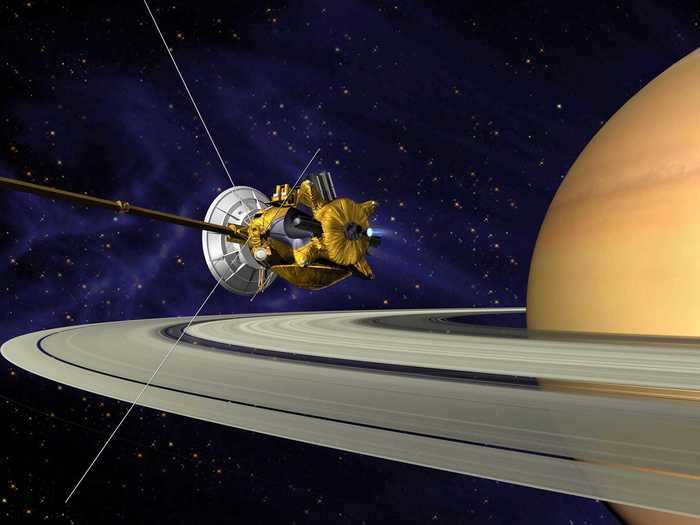

Carrying a whopping 72 lbs (33 kg) of nuclear material — the most Pu-238 of any spacecraft ever launched — Cassini faced heated public opposition before its 1997 launch toward Saturn.

Some people were worried the material might spread during an accident in Earth's atmosphere during launch. They were also worried it might happen about two years after launch, when Cassini would make a speed-boosting gravity assist past Earth.

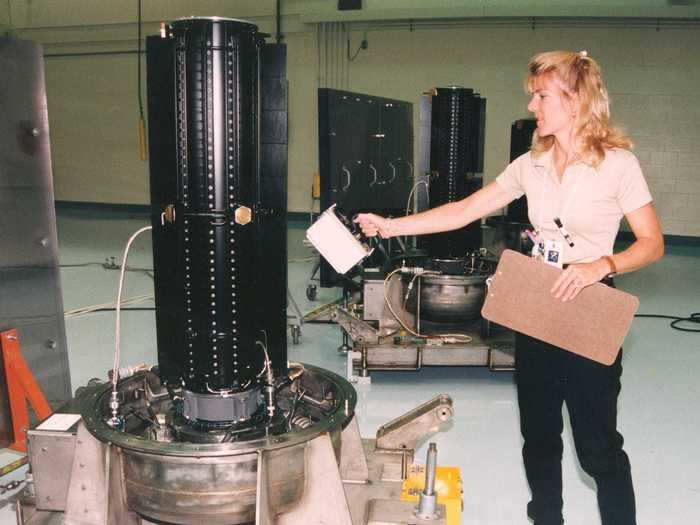

cassini nuclear power source plutonium nasa flickr 238 9460706328_ed75655c41_o

However, an information campaign — which included details about the many safeguards built into nuclear batteries — plus additional safety tests eventually quelled most of the public's fears.

cassini radioisotope power source rps nuclear battery plutonium 238 nasa jpl 7513_97pc1536

Cassini's three nuclear batteries allowed it to beam back more data than any deep-space probe in history.

Slide Embed

from on Vimeo.

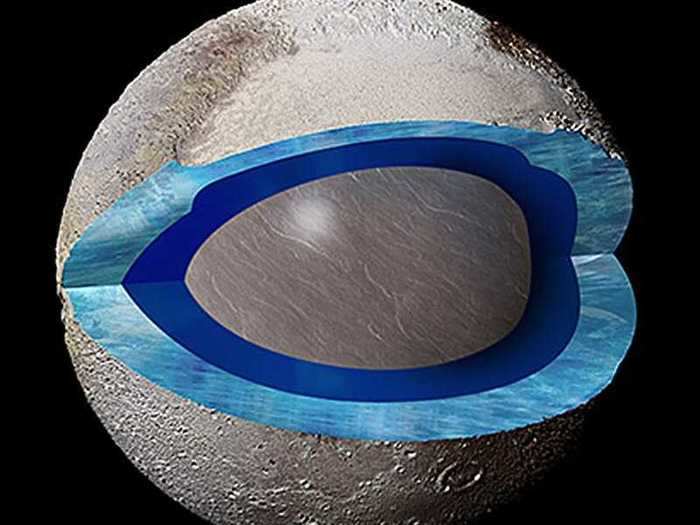

Cassini arrived at Saturn on Christmas Day in 2004, dropped a lander named Huygens on the moon Titan, discovered moonlets in the planet's rings, recorded Saturn's polar auroras, zoomed through and "sniffed" the icy jets of the moon Enceladus, found evidence of a global subsurface ocean, and more.

Slide Embed

New Horizons Pluto probe

New Horizons became the first-ever Earth visitor to the dwarf planet Pluto and its ensemble of moons.

It took nine years of travel — a journey it could not have survived without Pu-238.

pluto dwarf planet charon moon new horizons nasa jhuapl swri

The spacecraft launched in 2006 toward Pluto at roughly 36,000 mph (58,000 kph).

That was far too fast to dip into orbit around Pluto, but the spacecraft squeezed in a solid 6 months of observations around its flyby date of July 14, 2015.

pluto atmosphere blue ring nasa

New Horizons' single nuclear battery enabled observations of the dwarf planet and its five known moons — Charon, Nix, Hydra, P1 and P2.

pluto subsurface ocean ucsc

From revealing the oceanic origins of Pluto's newly discovered heart to its giant tail in space, the spacecraft's photos and discoveries have proven remarkable at every turn.

This Jan. 1, 2019 image from NASA shows Arrokoth, the farthest, most primitive object in the Solar System ever to be visited by a spacecraft. Astronomers reported Thursday, Feb. 13, 2020 that this pristine, primordial cosmic body photographed by the New Horizons probe is relatively smooth with far fewer craters than expected. It's also entirely ultrared, or highly reflective, which is commonplace in the faraway Twilight Zone of our solar system known as the the Kuiper Belt. (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Roman Tkachenko via AP)

Since departing the Pluto system, New Horizons has carried on in the Kuiper Belt to visit other trans-Neptunian objects.

On New Year's Day in 2019, the spacecraft flew by an object called 486958 Arrokoth — also known as 2014 MU69 or Ultima Thule. The two-lobed, red-hued, and seemingly pancake-like space rock is one of the most pristine and ancient in the solar system, a sort of "planetary embryo" that shows what rocky worlds were built by.

NASA is still determining which strange new planetary objects in deep-freeze that New Horizons will fly by in the 2020s and 2030s — follow-on missions that would be impossible without Pu-238.

Curiosity Mars rover (Mars Science Laboratory)

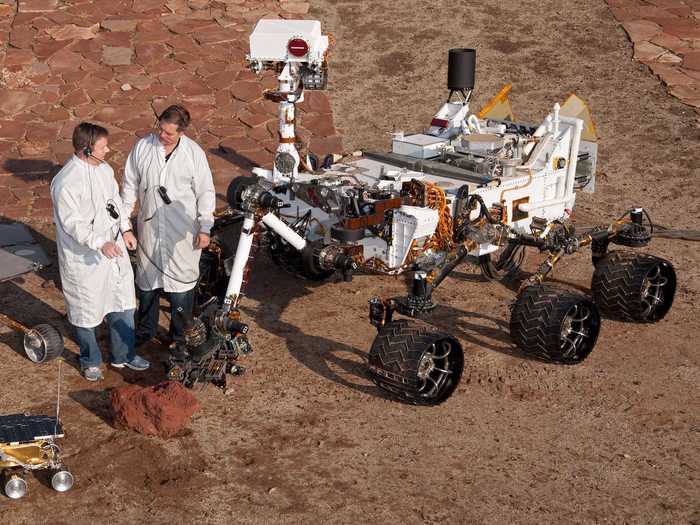

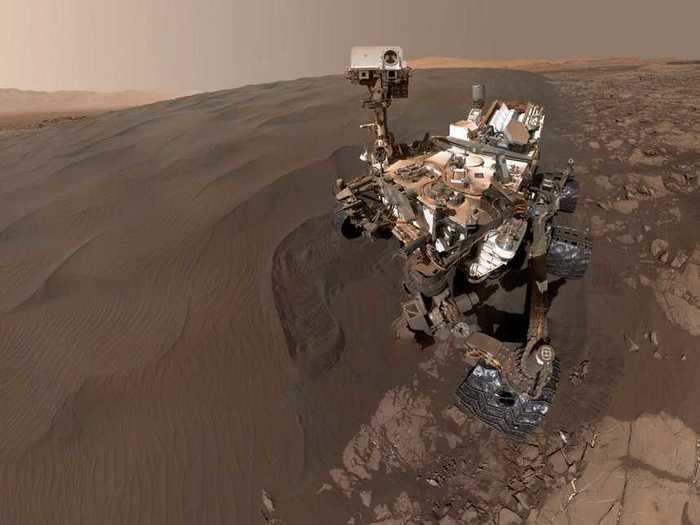

NASA's car-sized Curiosity rover landed safely on Mars on August 5, 2012 after surviving a harrowing descent known to engineers as the "7 minutes of terror."

curiosity

The robot is equipped with everything from a stereoscopic camera and a powerful microscope to a rock-zapping infrared laser and an X-ray spectrometer to perform advanced science on the red planet.

curiosity mars rover nasa jpl caltech

Unlike previous wheeled rovers on Mars, which only used bits of Pu-238 to warm their circuit boards (and relied entirely on solar power), one 125-watt nuclear powers source feeds Curiosity.

The power source should be strong enough to keep the rover rolling around Mars' mountainous Gale Crater for about 14 years.

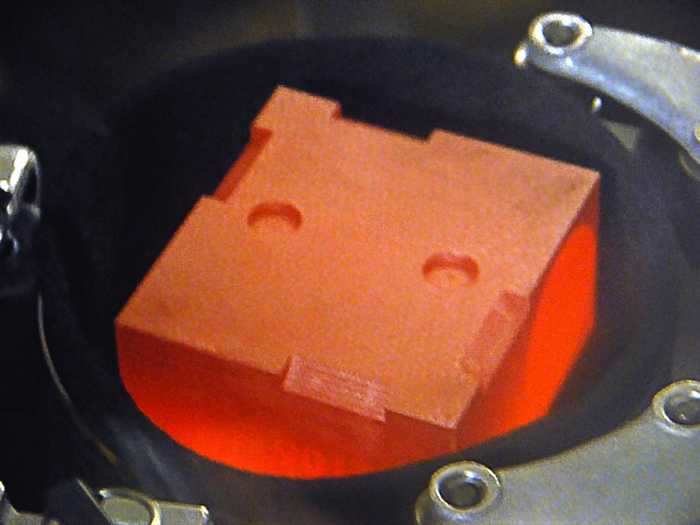

gphs glowing putonium 238 nasa

Curiosity harbors some of the last Pu-238 in NASA's old reserves. The spacecraft uses about 10.6 lbs (4.8 kg), leaving the space agency with roughly 37 lbs of usable plutonium.

The DOE and NASA have worked to make new Pu-238 and refresh about 35 lbs (16 kg) of material that has decayed over the years. Mission managers say a new robot-automated process can help them make nearly one pound (400 grams) of new material a year, working toward 3.3 lbs (1.5 kilograms) per year starting in the mid-2020s.

Though the price of Pu-238 is difficult to estimate due to shared infrastructure costs and varying output of the material, it likely costs thousands of dollars per gram, making it among the most expensive substances known by weight.

Perseverance rover (Mars 2020)

NASA used about one-third of what usable Pu-238 it had left to power the Mars 2020 Perseverance mission.

The rover is almost identical to Curiosity, but it harbors a unique new tool set to explore Mars — and comes with the first interplanetary helicopter.

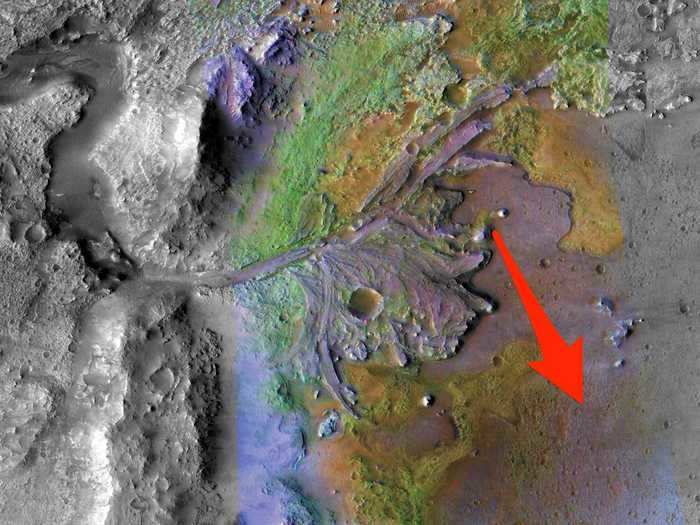

nasa mars 2020 rover landing site jezero crater labeled

NASA will attempt to land the nuclear-powered rover on February 18, 2021, at this location in Jezero Crater, where the space agency will collect its first Martian soil samples for a future rocket launch to Earth.

Dragonfly

NASA's next Pu-238-powered mission will be the Dragonfly helicopter, which aims to explore the skies and surface of Saturn's moon Titan.

Dragonfly is supposed to launch in 2026 and land in 2034. Once it lands, the drone will fly about five miles per excursion, racking up perhaps 100 miles total, to visually document the icy moon's features, sample its strange soils, and seek out possible signs of life on Titan's surface.

Pu-238 will be essential not only to powering the vehicle, but also keeping its components functioning in the minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 179 degrees Celsius) cold.

jupiter europa orbiter jeo concept nasa 515095main_europa20110204 full

Space scientists have dreamed up many more plutonium-powered missions, including a nuclear-powered boat for Saturn's moon Titan (which may have the ingredients for life) and a long-lived orbiter of Jupiter's moon Europa (which is thought to harbor an ocean bigger than all of Earth's watery territory).

Though many have fallen by the wayside with technical, budgetary, and Pu-238 supply constraints, some may see resurrection as NASA and the DOE work together to reestablish American supplies of the unique nuclear material.

This is an updated an expanded version of a story first published at Wired by Dave Mosher, the author and copyright holder.

READ MORE ARTICLES ON

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement