I went on the Silicon Valley diet craze that encourages butter and bacon for 2 months - and it vastly improved my life

I am no stranger to diets. I've cut sugar, counted points on Weight Watchers, and swapped solid food for Soylent, a venture-capital-backed meal-replacement shake.

But those usually don't last long. I love food. I'm a chronic snacker.

When I first learned about the keto diet, it caught my interest because dieters could eat seemingly unlimited amounts of healthy fats, like cheese, nuts, avocado, eggs, butter — foods that have high "point values" on Weight Watchers and are severely restricted.

The keto diet reorganizes the building blocks of the food pyramid.

It cuts down carbs to between 20 and 50 grams a day, depending on a person's medical history and insulin sensitivity. (There are about 30 grams in one apple or one-half of a plain bagel.)

On the diet, healthy fats should account for approximately 80% of a person's daily calories, while protein should make up about 20%. On average, Americans get about 50% of their calories from carbs, 30% from fat, and 15% from protein, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The keto diet is like Atkins on steroids. It turns the body into a fat-burning machine.

The human body breaks down carbohydrates into glucose, which is used for energy or stored as glycogen in liver and muscle tissue. But the body has a plan-B fuel supply.

When carbs go missing from a person's diet, the body uses up its glucose reserves and then breaks down stored fat into fatty acids. When fatty acids reach the liver, they're converted into an organic substance called ketones. The brain and other organs feed on ketones in a process called ketosis, which gives the diet its name. Keto-dieters eat lots of fat to maintain this state.

While the low-carb diet dates back to the 1920s, when it was shown to reduce seizures in people living with epilepsy, Dr. Robert Atkins popularized a version of it in the '60s and '70s.

Like the keto diet, the Atkins diet restricts carb consumption to 20 to 25 grams a day during an introductory phase, but then ramps up to 80 to 100 grams a day. So it's less strict than keto.

But the keto diet is not for everyone, so I sought medical supervision. Dr. Priyanka Wali is an internal-medicine physician with specialty training in obesity medicine. She uses the keto diet routinely for her patients who have insulin resistance, pre-diabetes, and diabetes.

In 2014, Wali was moonlighting at a weight-loss clinic in San Francisco, where she saw her patients struggle to stick to their strict diet programs and maintain their weight loss. She started reading studies on low-carb diets and became convinced it was the solution.

Wali made herself a guinea pig before she prescribed the diet. And it worked.

She said she "expected to feel a lot of adverse side effects" from eating so much fat, "but what ended up happening was I felt great. I started to have more energy and concentration. I didn't lose weight, but my fat distribution changed, so I lost weight from my hips."

After asking me about my family history and my reasons for trying the keto diet, Wali determined I was an "optimizer," like the healthy tech workers who rely on the diet.

Tech workers living in the Bay Area sometimes go to extreme lengths to improve their bodies and minds. For example, at the supplements startup HVMN (formerly known as Nootrobox), most employees don't eat on Tuesdays — a ritual they say improves ketone production and productivity. Intermittent fasting has been shown to assist ketosis.

To see if I was a good fit for the keto diet, Wali requested I have some lab work done, including a cholesterol panel and a fasting insulin level test. My results came back normal, which meant there was no medical necessity for me to go on the diet. If I were pre-diabetic or insulin-resistant, Wali would have been more likely to make the keto diet part of my treatment.

Wali introduced me to the "keto food pyramid," via this image that went viral on Reddit.

We agreed that for my first week on the keto diet, I would aim for 30 to 50 grams of carbs during the day and eat regular, carb-heavy dinners, even if they took me over the limit.

"Sugar addiction is a real thing," Wali warned me in our first meeting. She wanted me to ease into ketosis to avoid "carbohydrate withdrawal," which can cause irritability, depression, headaches, lethargy, and nausea. I was happy to take it slow.

As I was learning the carb loads of different foods in those first few weeks, I tracked my meals on the Fitbit and Weight Watchers apps, but Wali says paper and pen works just as well.

She taught me how to count carbs the smart way: Carbohydrates - dietary fiber = net carbs.

Fiber is a carbohydrate that the body can't digest. It doesn't raise blood-sugar levels, so there's no use in counting grams of dietary fiber toward a daily carbohydrate goal.

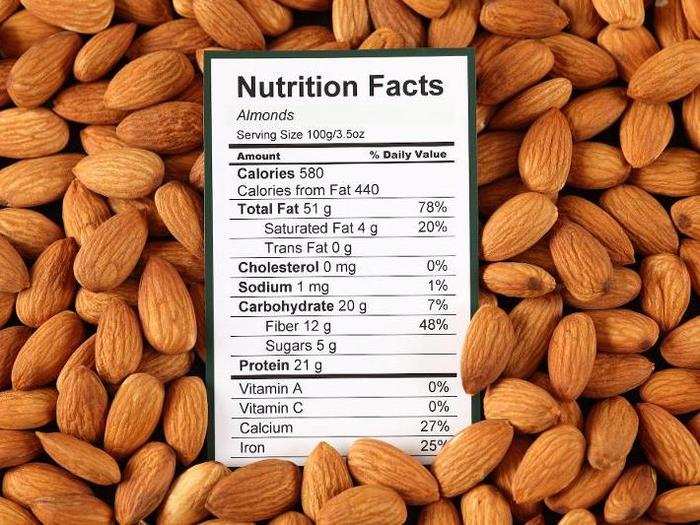

A cup of almonds has approximately 20 grams of carbohydrates, but 12 of those come from dietary fiber. As a result, I had to count only 8 grams for the serving. What a bargain!

Pasta was off the menu. A cup of cooked whole-wheat noodles has about 41 net carbs, which would blow through my daily carb allowance in one small portion.

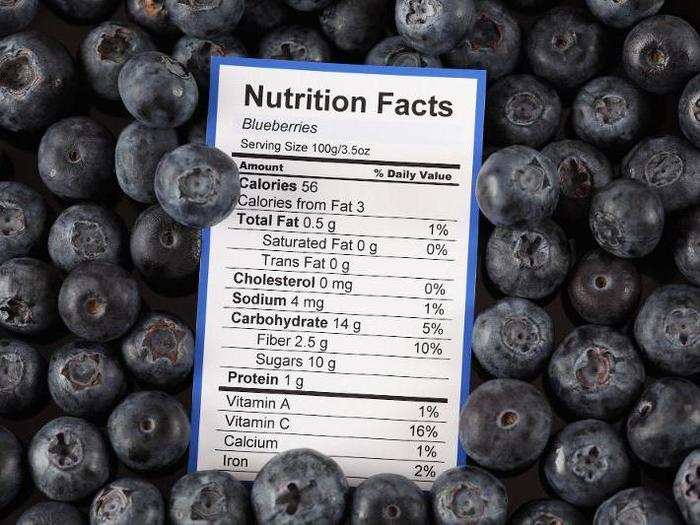

I had to be careful even with fruits and starchy vegetables. A cup of blueberries has about 11.5 net carbs. It's also low in fiber, so it's not very filling for long.

When I got home from my visit with Wali, I was forced to rethink all my dietary staples. I let my boyfriend finish off our supply of apples, bananas, bread, pasta, rice, and potatoes.

And I said yes to fat. A typical breakfast included a coffee with half and half, along with cheesy eggs cooked in butter and two slices of bacon.

Some mornings I scrambled to find 20 minutes to make breakfast. Few restaurants had dishes that met my dietary restrictions. I ate a sad, tortilla-less breakfast burrito once.

I managed to find one restaurant, La Boulangerie in San Francisco, that makes scrambled eggs with mix-ins to order. I swapped potatoes for a side salad and tossed the toast. It cost $11.

For lunch, I ate a lot of "sad desk salads." Two cups of leafy greens, an ounce of cheddar cheese, a handful of nuts, and avocado or cauliflower rang up about 6 net carbs.

Our office has the best snacks — Goldfish, Nature Valley bars, animal crackers, and peanut-butter-filled pretzels (my personal brand of indulgence). I thought of them often.

I used to snack every hour between 10 a.m. and dinner. Food was always on my mind.

In my first week, I dug up the willpower to resist those sugar binges. But it was not without consequences. My headaches pounded for hours on end. My mind said, "Eat something."

Wali recommended I drink more water and salt my food to ease the headaches.

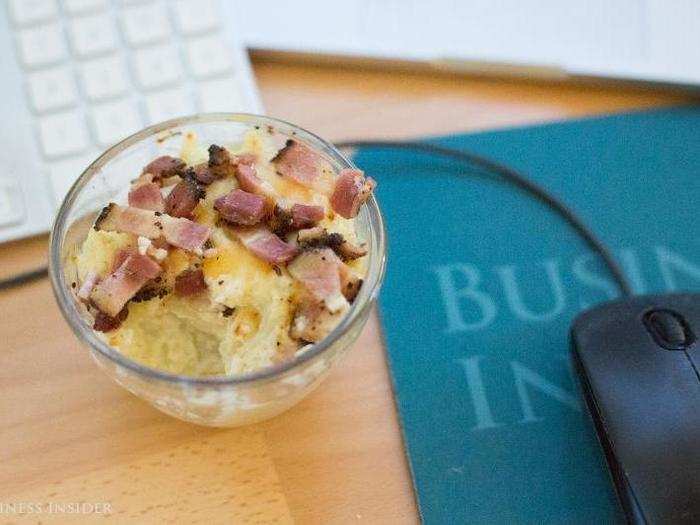

I scoured keto blogs for high-fat snacks — called "fat bombs" — to power me through the sugar cravings. Loaded cauliflower made with butter, sour cream, cheddar cheese, and bacon became my go-to treat. The keto comfort food didn't make me feel deprived.

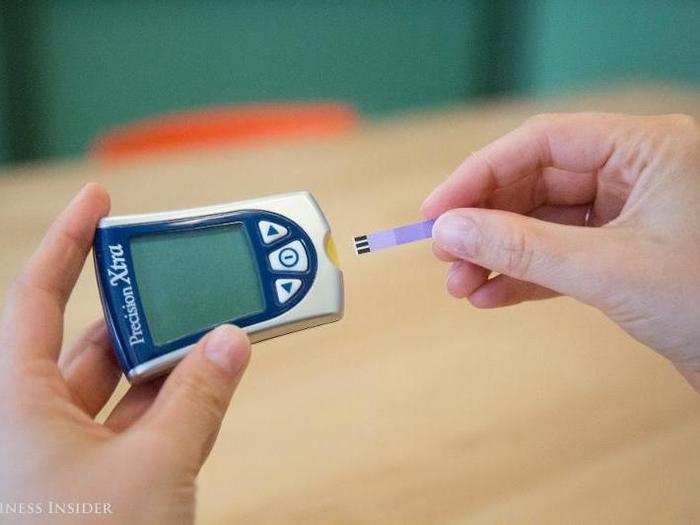

During Week 2, my ketone testing meter kit arrived in the mail. The pocket-sized medical device uses a small blood sample to measure the presence of ketones.

People diagnosed with diabetes can have a ketone testing meter prescribed by a doctor, but it may not be covered by insurance. Optimizers like me turn to Amazon for third-party sellers.

I bought the Precision Xtra Glucose Meter Kit (which also measures ketones) for $22, and a 10-pack of ketone testing strips for $42. The meter has since gone up to $99 on Amazon.

Keto adherents use ketone testing meters to check that they're in a state of nutritional ketosis, which is generally considered above 0.3 millimoles per liter of blood, according to Wali.

Entrepreneurs sometimes share their ketone levels on social media. It's the biohacking community's equivalent of posting photos of a bathroom scale to celebrate recent weight loss.

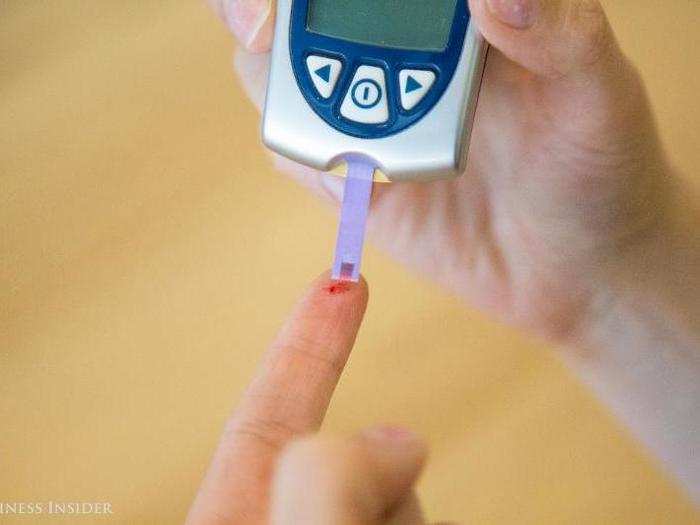

My first encounter with a lancing device, a tool that draws blood from the fingertip, was not particularly pleasant. Afterward, I held the ketone testing meter to the drop of blood.

I got 0.4 mmol/L, a low-level state of nutritional ketosis. In less than two weeks on the diet, my body flipped the switch on burning carbs to burning fat as its primary fuel source.

Three weeks in, I felt the difference. Even on days when I ate bun-less cheeseburgers for lunch, my energy was sky-high. I no longer needed coffee to stay awake in the afternoon.

I suddenly could go three, four, even five hours without thinking about food. My snacking became much less frequent, and I became more focused on work as a result.

Dr. Jason Fung, who specializes in kidney care, offers an analogy in his book "The Obesity Code": Imagine sitting down to an all-you-can-eat buffet. At some point, the idea of eating one more pork chop becomes sickening. But if the dessert cart passes, it's hard to resist.

That's because highly refined carb-filled foods, like cake and pie, don't trigger hormones in the brain that say, "You're full. Stop eating." Proteins and fat can signal when you've had enough.

When I splurged on a bagel or pizza, which did happen, I wanted to curl up under my desk and nap within 30 minutes of eating. I felt uncomfortably full and groggy.

The worst part of cheating was that it had the potential to reverse a state of nutritional ketosis.

When my parents came into town over one weekend and I went rogue, I wound up with a ketone reading of 0.3 mmol/L, which meant my body was burning more carbs than fat.

I returned to the diet on Monday, but it takes an average of five days for the body to use up the leftover glycogen reserves and return to nutritional ketosis, according to Wali.

To avoid the ill feelings that carbs gave me, I experimented more in the kitchen. I learned that pizza made with a baked cauliflower crust was not pizza. It tastes like a vegetable casserole, but at least I don't wake up feeling bloated.

Eating at restaurants was the hardest part. I ate taco fillings out of tortillas and scraped the breading off fried chicken. Every menu had just one or two things I could order guilt-free.

After eating mostly fat, protein, and leafy vegetables for one month, I reached my peak ketone reading of 0.9 mmol/L — a strong indication that I reached a state of ketosis.

By this point in my journey, most of the negative side effects had subsided. (I experienced leg cramps and tingling sensations in my feet, which Wali explained was from eating too little salt. She suggested I try magnesium supplements, and the problem went away within days.)

A ketone reading of 0.9 mmol/L indicates a mild state of ketosis. Dieters can reach higher levels — "go deeper" into ketosis — by restricting carbs to fewer than 20 grams a day or fasting. But there isn't consensus in the medical community that doing so unlocks additional benefits.

Geoff Woo, the cofounder and CEO of HVMN, said he aimed for 3.0 mmol/L or higher, which he achieves through intermittent fasts that spike ketone production, for "optimal mental flow."

When I started to obsess over the numbers my ketone testing meter gave me, Wali encouraged me to focus on how I felt instead.

It was then that I realized why I loved eating keto — it made me feel like a superhero.

When I lost 30 pounds on Weight Watchers in college, I celebrated the numbers on the scale and how my clothes fit. But because I continued to eat carbs in smaller portions, I was still prone to sugar crashes and afternoon "brain fog." The transformation was incomplete.

The keto diet made over my mind and my body. The sense of mental clarity and energy that came on about three to four weeks into eating keto was unlike anything I've experienced. I woke up feeling strong, confident, and capable of taking on whatever the day threw at me.

"This is how you're supposed to feel as a human being," Wali said during a follow-up visit.

I also lost about 8 pounds in two months, without added exercise. It was a nice bonus!

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement