Courtesy: Carolina Reid, Jake Eberts

- Clinical trials are a critical part of how new vaccines, treatments, and drugs are developed.

- This year, Insider interviewed patients who volunteered to get malaria and dysentery for clinical trials.

One volunteer drank a bacteria-filled smoothie knowing it could give him dysentery.

Another let hundreds of malaria-carrying mosquitoes bite her arm, not just once but on five separate occasions.

And — in a first-of-its kind attempt in the US — a man agreed to let a newly installed stent read his thoughts forever.

None of them regret the daring things they did for science in 2022.

These are the three of the wildest, most-out there contributions people made to scientific advancements through their participation in clinical trials this year — and why the patients all say they wouldn't hesitate to do something like this again.

Carolina Reid, a chef in Seattle, got bit by more than 600 mosquitoes for $4,200

Carolina Reid

Reid was part of a malaria vaccine trial — and the mosquitoes were her vaccinators. The bites delivered a modified sporozoite, a kind of parasite, which scientists hoped would train her body to fight off malaria.

It wasn't Reid's first clinical trial, and she says it won't be her last. She's also participated in Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine research, and trialed a bird flu vaccine.

Reid's study participation had to be cut short when she got malaria

Reid, getting blood drawn at one of her many clinic visits. Carolina Reid

Reid said learning she contracted malaria was "kind of emotional," and she burst into tears.

"When like the news comes, you're like, 'oh my god, this is not the cure for malaria," she said.

Challenge trials are a critical part of medical research, because they give scientists a controlled environment to figure out how well different people's bodies respond to new treatments or vaccines.

"I'm able bodied, and all the boxes are checked, and I don't have a reason not to do this," Reid said, expressing her confidence in the safety checks and balances of today's medical research rules. "It's generally for the better good of things."

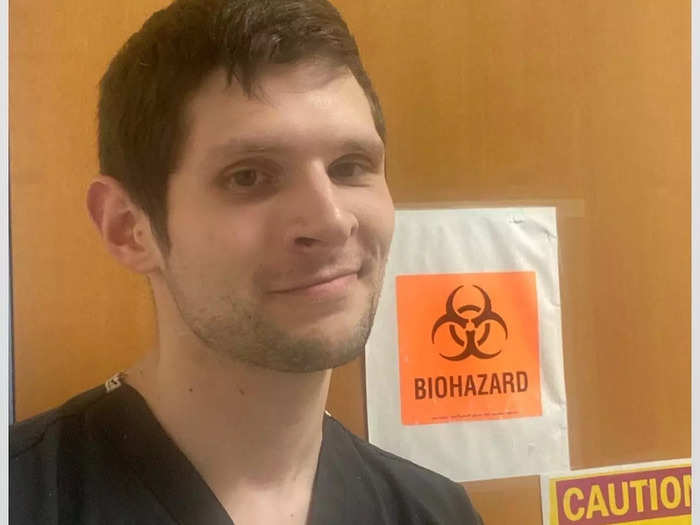

26-year-old Jake Eberts willfully drank a bacteria-filled smoothie, and got 'brutally sick' because of it

@wokeglobaltimes

Eberts was part of a tightly-controlled inpatient challenge study of a new dysentery vaccine.

The "smoothie," as he called it, was part of how scientists figure out how well the vaccine really works — by challenging people with the bacteria, some who've been vaccinated, and some who haven't — researchers can glean in-depth insights into how well new shots work.

Dysentery kills hundreds of thousands of children and older adults around the world every year. It is the second-leading cause of diarrhea death globally, but there is no vaccine for it — at least, not yet.

Ebert said he'd gladly do a trial like this one again, both for the $7,000 paycheck, and for the cause.

Left: The dorms where study participants stayed. Right: a bedpan like the ones that Eberts had to use every time he went to the bathroom, so that researchers could extract a sample from it, and analyze his illness. @wokeglobaltimes

"I don't want to make myself out to be Mother Teresa here — would not have done this for free," he told Insider. "It's a big ask to ask someone to get dysentery."

Eberts experienced fever, dehydration, cramps, chills, exhaustion, and bloody diarrhea over a period he referred to as "the worst eight hours of my life."

"I was exhausted and felt miserable, but I didn't feel fear," he said.

He knew that his medical team was watching his every move, monitoring his vital signs, and antibiotics were prescribed quickly to treat his infection, kicking in within a matter of hours.

Eberts even got a new job out of the experiment

Jake Eberts during his inpatient vaccine "challenge" trial at the University of Maryland. Courtesy of Jake Eberts

He now works in the communications department at "One Day Sooner," a nonprofit advocacy group for people who participate in high-stakes clinical research trials.

"Some people go to soup kitchens to get their charity fix. This might be the way I do it," Eberts said.

He's planning to enroll in a malaria challenge trial next, where he'll get deliberately exposed to the parasite, like Reid did.

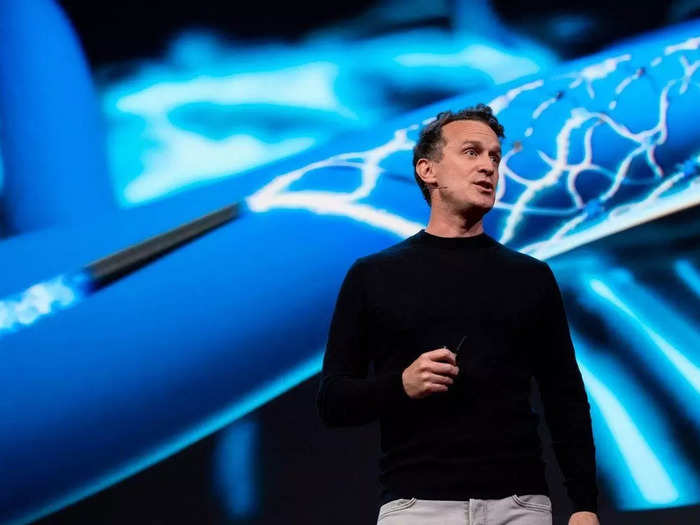

Finally, a man living near New York City was implanted with a piece of platinum that will read his thoughts

A photo of Philip O'Keefe, an Australian patient, who was one of the first in the world to be implanted with the brain-computer interface, called Stentrode. Paul Burston, The University of Melbourne

This experiment was a first of its kind FDA trial of a brain-computer interface.

The man, whose identity has not been revealed, has ALS and cannot move his hands.

He can now type out an email saying "hi" to his caregiver or search "pharmacies" on Google — using just his mind and a tiny electrode-laden device implanted inside a key blood vessel in his brain, as Insider previously reported.

Brain-computer-interface devices may one day be used to diagnose diseases, or even prevent and treat issues like seizures.

Thomas Oxley, the CEO of BCI company Synchron, in front of a picture of the technology he developed, which is implanted in key blood vessels in the brain. Synchron

For now, patients are using BCI devices like Synchron's as assistive devices, to help them navigate the digital world, and gain back some independence, by harnessing thoughts into actions like clicks on a computer screen.

"It's not an easy task to learn, it's quite cerebral and challenging, but he's doing great," Mount Sinai Director of Rehabilitation Innovation David Putrino said of the anonymous patient. "He has a really powerful desire to help the community."