- Home

- Science

- Environment

- THE SUMMIT: The Story Of The Deadliest Day On The World's Most Dangerous Mountain

THE SUMMIT: The Story Of The Deadliest Day On The World's Most Dangerous Mountain

Located on the western edge of the Himalayas, K2 is found at the center of the Karakoram Mountain range in northern Pakistan.

K2 is slightly shorter than Everest, but more dangerous to mountaineers because it is more difficult to climb and has notoriously bad weather since it is farther north.

Of the roughly 300 climbers who have reached the top of K2, more than one-quarter of them died on the way down.

Meaning for every four climbers who successfully summit K2, one person dies trying.

Only two other 8,000-meter-plus peaks, Pakistan's Nanga Parbat and Nepal's Annapurna, have higher death ratios.

The tragedy that occurred on K2 in 2008 was preceded by two months of preparation on the mountain.

Around 200 climbers from various expeditions, including Serbia, South Korea, Italy, Norway, the Netherlands, and the United States, arrived at the K2 base camp in June.

The climbers spent several weeks setting up camps at different altitudes and acclimatizing to the thin air.

The plan, according to Dutch team leader Wilco Van Rooijen, was to summit K2 in July.

But that summer all of the teams were delayed by three weeks because of relentless snow storms.

Aug. 1 was the first clear day, so after nearly a month of waiting the 22 climbers who had made it to Camp 4 — the final camp before the summit — were ready to push.

According to Van Rooijen, there was a group meeting among expedition leaders the night before the climb to decide how they were going to tackle the last part of the mountain as one team.

In retrospect, the decision to share responsibly rather than have each expedition work independently turned out be a fatal mistake.

At the meeting it was decided that Sherpas and Pakistani porters would set off from camp before midnight, July 31, to start preparing fixed rope going up the mountain.

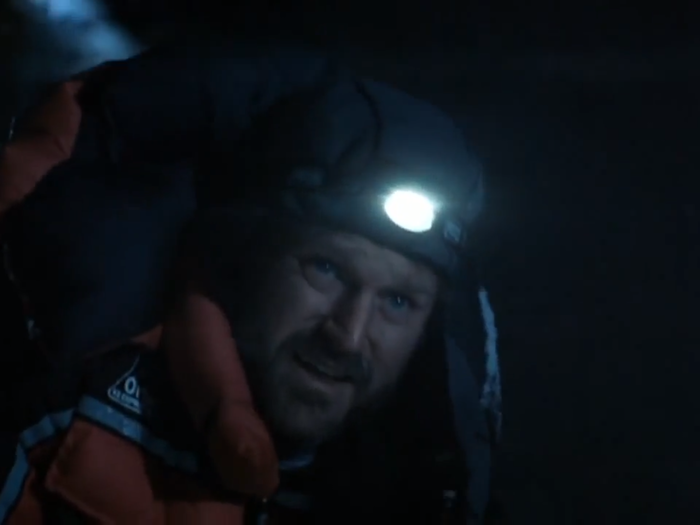

To reach the summit, climbers must pass through the Bottleneck, an extremely narrow and steep section of ice and snow located beneath a serac, a giant block of ice at the edge of a hanging glacier. Seracs are notoriously unstable. They can crack at any second, sending chunks of ice crashing down onto climbers.

According to the film, the leader of the Korean team had also agreed to wake up early and prepare fixed rope, but did not.

When the rest of the group started hiking around 3 a.m on Friday, they found that the lines had not been done properly. They were fixed very close to the Camp 4 site — where they were not needed — and the rope ran out just above the Bottleneck — where they were needed most.

As a result, the group had to take rope from lower portions of the trail and use it to prepare lines above the Bottleneck, creating serious delays. Further slowing things down were the large number of people pushing for the summit on the same day, due to the narrow weather-window of opportunity.

By 10 a.m., there was already a traffic jam in the Bottleneck, a portion of the route where hikers should be moving quickly to minimize danger from falling ice.

A Serbian climber, Dren Mandic, was the first to die in the Bottleneck. Mandic lost his balance and slid more than 300 feet down the steep corridor after unclipping his rope to let other hikers pass.

On his way down he knocked into Cecile Skog from the Norway expedition. Skog was still clipped into her rope and avoided being dragged down the mountain.

Some climbers at Camp 4 saw the fall and sent a rescue team to recover Mandic, whom they thought was still alive.

Two members from the Serbian team and their porter also scurried back down the mountain to rescue their fallen team member. The Serbs were joined by another Pakistani porter, Jehan Baig.

As the group started to lower Mandic's body down the mountain, it was clear that something was wrong with Baig. He was incoherent and unsteady on his feet — signs of high altitude sickness.

Baig lost his footing and let go of the rope that was attached to Mandic's harness. Without making an attempt to stop his slide, Baig fell to his death.

Meanwhile, most climbers in the Bottleneck were already on the move again. As it's told in the documentary, the other mountaineers deliberated for about three or four minutes after Mandic's fall before deciding to press on.

When a climber falls or wanders off the trail, it's an unwritten code of the mountain to leave them for dead, according to the film.

The first person to reach K2's summit was Spaniard Alberto Zerain at 3 p.m., who was hiking solo. In the film, Norwegian climber Lars Nessa describes Zerain as a "mythic figure." Zerain seems to make it up and down the mountain without much trouble.

Two members of the Norwegian team, Cecile Skog and Lars Nessa, reached the top around 5 p.m. (Skog's husband, Rolf Bae, was also part of the expedition but did not summit).

The Dutch team, including leader Wilco Van Rooijen, Cas van de Gevel, Ger McDonnell (the first Irishman to summit K2), and Pemba Gyalje, reached the top around 7 p.m.

They were joined by Italian climber Marco Confortola.

A total of 18 climbers summited that day, some as late as 8 p.m, around 16 hours after leaving Camp 4.

But the excitement was short-lived. As the sun went down, and climbers attempted to make their way back down the Bottleneck, a massive slab of ice snapped.

Cecile Skog watched her husband, Rolf Bae, get swept away by ice right in front of her eyes.

The falling ice sliced through the fixed ropes that were needed to get back down the mountain.

Skog and her team member, Lars Nessa, managed to reach Camp 4 without the lines, but more than a dozen climbers were left trapped in the "death zone" — above 26,000 feet — where temperatures at night can hit minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit and the air is so thin that there's hardly enough oxygen for a human to breathe.

Chaos ensued. Without the rope, many climbers lost their way. “People were running down, but didn't know where to go, so a lot of people were lost on the mountain on the wrong side, wrong route — and then you have a big problem,” Van Rooijen told The New York Times in the aftermath of the disaster.

Some people, including McDonnell, Van Rooijen, and Confortola decided to wait until morning to descend the mountain.

Pemba continued down the mountain in darkness and without ropes, reaching Camp 4 before midnight on Aug. 1.

Van Rooijen set out early Saturday morning before the other two members of his group, but ended up getting lost.

This is where many of the details get sketchy. According to Confortola, he and McDonnell began descending on Saturday morning, but stopped to help three stranded members from the Korean team.

After about two hours of unsuccessfully trying to free the Korean climbers, Confortola claims that McDonnell started to hike back up the mountain. McDonnell was never seen alive again. He is believed to have been killed by another ice fall.

Confortola continued to descend after McDonnell allegedly wandered back up, leaving the Korean climbers behind. The Irishman is believed to have succumbed to high altitude sickness.

Pemba — who has been painted as the hero of the K2 tragedy — managed to rescue Confortola and return to Camp 4.

That evening he went out again to save Van Rooijen who had spent more than a day in the death zone without water or an ice axe.

Confortola and Van Rooijen were airlifted from the mountainside by Pakistani rescue helicopters.

Of the Dutch team, only Pemba remained at K2's base camp, pulling together the pieces of what went wrong over a horrific 48 hours.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement