These are the 25 animals that scientists want to bring back from extinction

During their prime, Caspian tigers could be found in Turkey and through much of Central Asia, including Iran and Iraq, and in Northwestern China as well, but they went extinct in the 1960s. Some scientists want to bring them back by reintroducing the nearly-identical Siberian tiger to its old habitats, where they expect it to adapt.

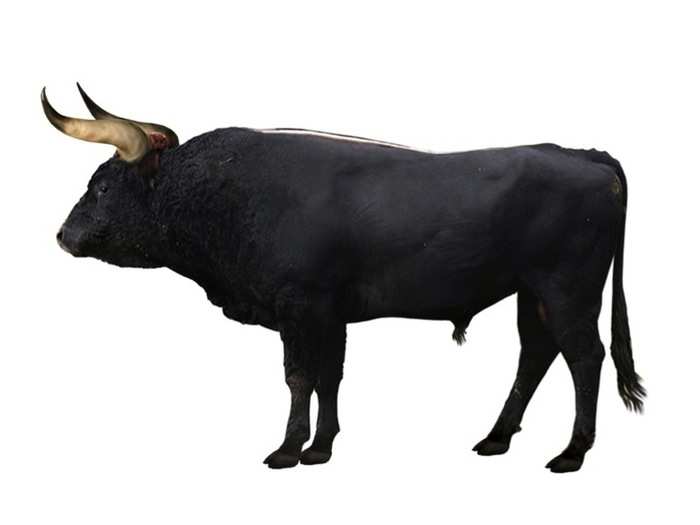

The aurochs is an ancestor of domestic cattle that lived throughout Europe, Asia, and North Africa. Scientists want to bring them back through selective breeding of cattle species that carry some aurochs DNA. To this end, European science teams have been selectively breeding cattle since 2009.

The Carolina Parakeet was a small, green parrot with a bright yellow head and orange face that was native to the eastern United States. The last wild one died in 1904 in Florida, but the genes that made them still linger in close relatives in Mexico and the Caribbean.

The vibrant Cuban macaw lived in Cuba and went extinct in 1885 due to hunting, trading and being captured as pets. Aviculturalists are rumoured to have bred birds that are similar in appearance, but slightly bigger, because they had similar genes.

The dodo is perhaps the most famous extinct animal. It evolved without any natural predators, but the humans that arrived on their home island, Mauritius, took advantage of this and killed them all for food. In 2007, scientists found the best preserved dodo skeleton ever, which may hold valuable DNA samples.

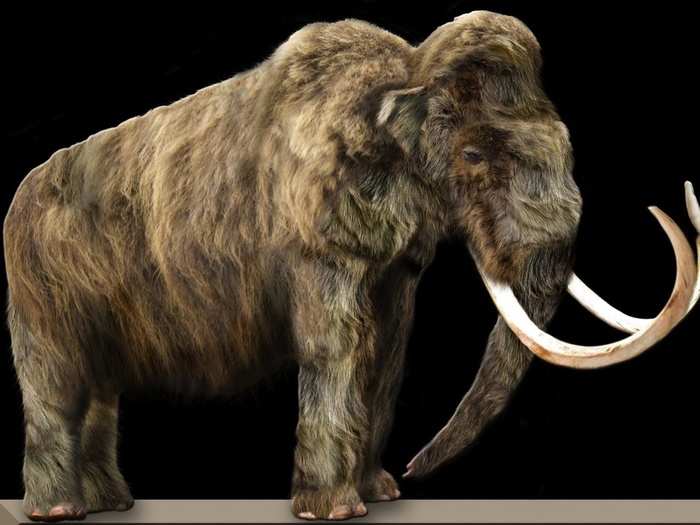

Woolly Mammoth carcasses have been frozen and preserved, which has allowed scientists to access well-preserved DNA. The last isolated population of woolly mammoths lived on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean until 4,000 years ago, but scientists contest whether we were to blame for their extinction.

Sources: Business Insider, 2014; Business Insider, 2015

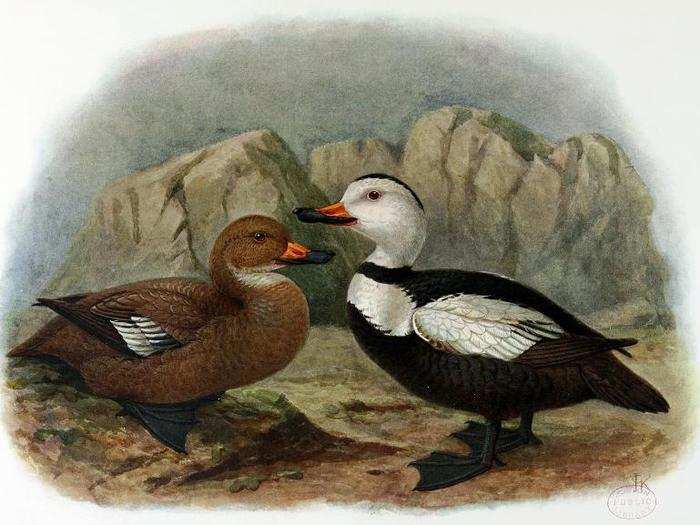

The Labrador Duck was always rare but disappeared between 1850 and 1870. Supposedly it didn't taste good, so it wasn't hunted extensively for food, but scientists believe we are responsible for their extinction nonetheless. This is why they want to bring them back.

The woolly rhinoceros was common throughout Europe and Asia. It had stocky legs and a thick woolly coat that made it well suited for the cold tundra environment during the ice age. Human hunting is often blamed for their extinction, so scientists want to re-introduce them to make up for it.

The Heath Hen lived in coastal North America up until 1932. They made for delicious dinners, and were likely the foundation of the Pilgrims' first Thanksgiving. We practically ate them all, which makes them another candidate for de-extinction.

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker lived in "virgin forests" of the southeastern United states, but there hasn't been a confirmed sighting of the bird since the 1940s. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology even offered a $50,000 reward for someone who could lead researchers to a living specimen.

The Imperial Woodpecker may actually still be alive, but hasn't been seen in more than 50 years. It is officially listed as "critically endangered (possibly extinct)" because a lot of its habitat was destroyed by humans. If it is extinct, scientists want to bring it back to make up for that.

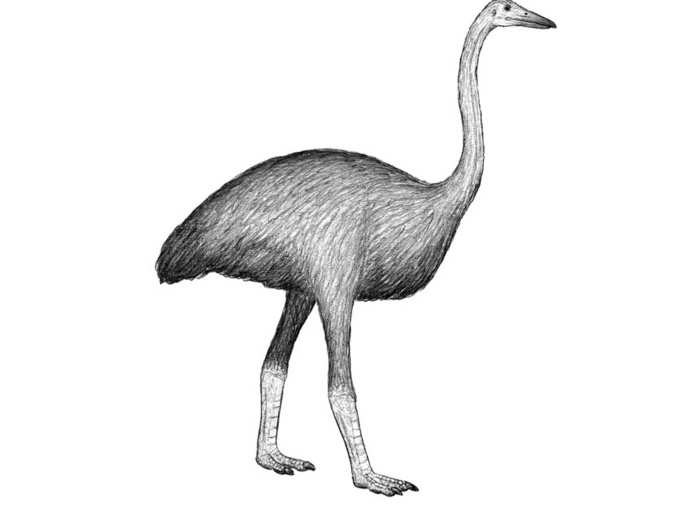

The Moa were a giant flightless bird from New Zealand that reached 12 feet tall and weighed more than 500 pounds. They died out because of over hunting by the Maori by 1400, and their closest relatives have been found to be the flighted South American tinamous, which could hold some of their genes.

This giant, flightless Elephant bird was found only on the island of Madagascar and died out by the 17th century. It is widely believed that they went extinct as a result of human activity, so we want to make up for that too.

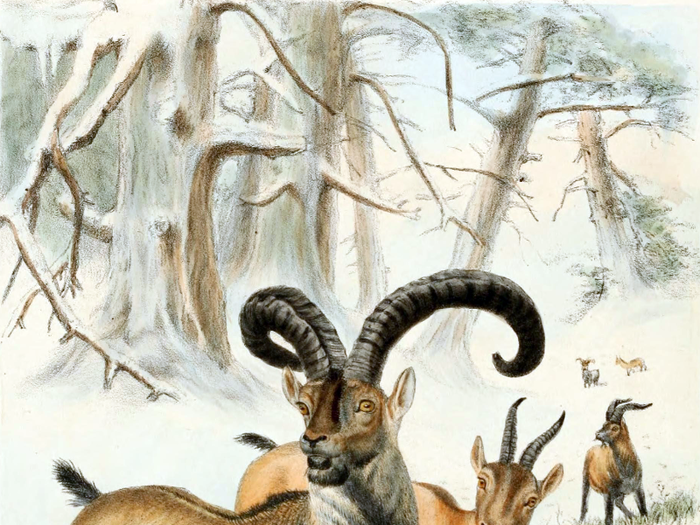

The Pyrenean ibex lived in Southern France and the Northern Pyrenees, but died out in January 2000. Scientists tried to clone one using DNA from one of the last females, but it died shortly after being born.

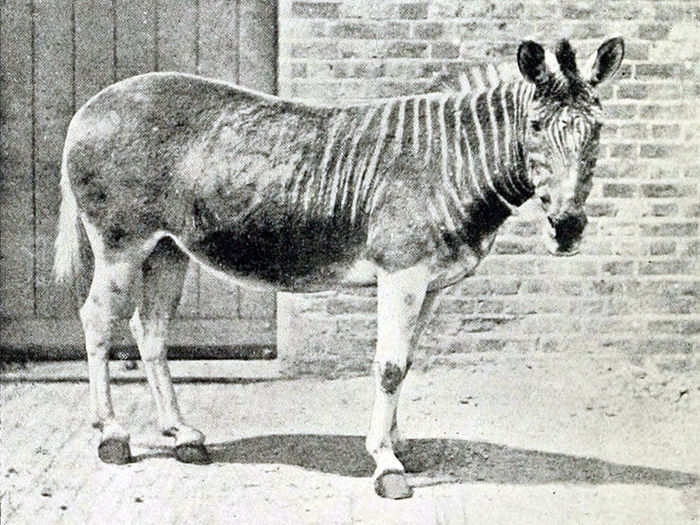

This extinct species of plains Zebra, the Quagga, once lived in South Africa. The last wild one was shot in 1870 and the last in captivity died in 1883. The Quagga Project, started in 1987, is an attempt to bring them back from extinction.

This freshwater dolphin is known as the Baiji and lived in the Yangtze River in China. It was declared extinct a decade ago, but scientists claimed to spot one in the river late last year. If some still are alive, conservation efforts will attempt to bring their populations up again.

The Thylacine, or Tasmanian Tiger, is the only marsupial to make the list. It's also probably not like any other marsupial you can name. It lived in Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea until the 1960s when it died out, but Tasmanian devils may carry some of its DNA.

Irish elks were one of the largest deer ever to walk the Earth. The most recent remains of the species have been carbon dated to about 7,700 years ago in Siberia. Red deer or fallow deer might have some similar genes.

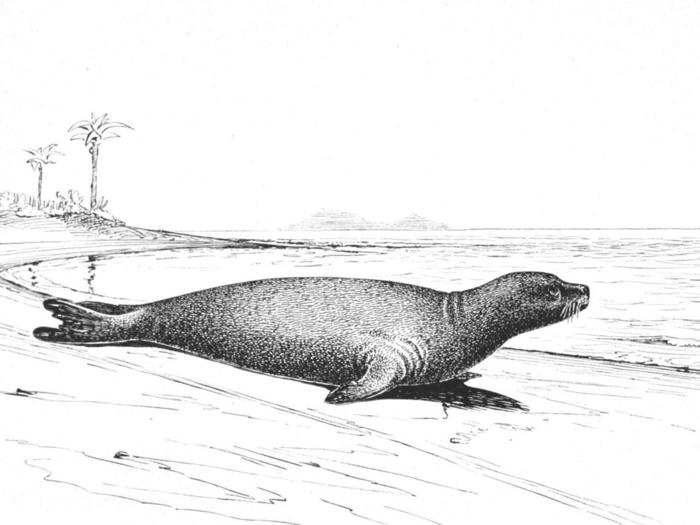

The Caribbean monk seal was hunted to extinction for use as oil, and they were out-competed for fish by humans and died out in 1952. They were closely related to Hawaiian monk seals, which live around the Hawaiian Islands, and Mediterranean monk seals, which are both endangered.

The Huia was a large species of New Zealand wattlebird. It went extinct in the 20th century because of hunting to make specimens for museums and private collectors. The female had a long, curved beak, while the male's was shorter. Very little is known about their actual biology, so bringing them back would be fascinating.

The Moho are a genus of extinct birds from Hawaii. Most of them died out because of habitat loss and hunting. The Hawaiian Moho seen here died out in 1934, but some birds like waxwings and the palmchat might carry remnants of their DNA.

The Steller's sea cow is related to the manatee and dugong, the two remaining species of sea cow. They were once abundant in the North Pacific, but within 27 years were hunted to extinction. Dugongs might still be carrying some of its DNA, which could be how scientists bring them back.

With so many pigeons around, it's hard to imagine a species going extinct. But that's what happened to the passenger pigeons, which died out after living in enormous flocks throughout the 20th century. It was hunted as food for slaves on a massive scale until the last one died in 1914. Passenger pigeons have several living relatives, including the 17 pigeons in the group Patagioenas.

This is the gastric-brooding frog, which swallowed its eggs and hatched them out of its mouth. It became extinct in 1983, but in 2013, scientists were able to implant a "dead" cell nucleus into a fresh egg from another frog species.

The Great Auk went extinct in the mid-19th century. They lived in the North Atlantic from Northern Spain through Canada. They died off because of a combination of climate changes during the Little Ice Age that brought predatory polar bears into their territories, and human hunting. So again, partially our fault.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement