15 disturbing consequences of eating too much sugar

Cavities.

Insatiable hunger.

The hormone leptin tells your body when you've had enough to eat. In people who develop leptin resistance, this "I'm full" signal is never received, presenting a major obstacle for weight control.

A few studies raise the possibility that leptin resistance may be a side effect of obesity, not a contributing cause. But research in rats suggests that over-consumption of fructose — as in high-fructose corn syrup, which is common in soda — can directly lead to higher-than-normal levels of leptin and reduce your body's sensitivity to the hormone. (Removing fructose from the rats' diets generally reversed those effects.)

"Our data indicate that ... fructose-induced leptin resistance accelerates high-fat induced obesity," concluded one study of rats. And high levels of leptin may actually be an early warning sign of the larger metabolic problems associated with drinking too much soda, a 2014 study found.

More research is needed to confirm sugar's connection to a bottomless appetite, but the results so far are worrisome.

Source: American Journal of Physiology, 2008; American Journal of Physiology, 2009;British Journal of Nutrition, 2011; Advances in Nutrition, 2012; Journal of Nutrition, 2014

Weight gain.

Other than adopting a completely sedentary lifestyle, few ways of packing on the pounds work as swiftly and assuredly as making sugar a staple of your diet.

Sugary foods are full of calories but do little to satisfy hunger. When researchers studied the eating habits of a large group of Japanese men, for example, they found "a significant association between sugar intake and weight gain" that held even after they accounted for other things like "age, body mass index (BMI), total [caloric] intake, alcohol, smoking and regular physical exercise."

That squares with a huge body of research on the subject. A 2013 review of 68 different studies found "consistent evidence that increasing or decreasing intake of dietary sugars from current levels of intake is associated with corresponding changes in body weight in adults."

Want to lose weight? Cutting your sugar intake is one of the best places to start.

Source: British Medical Journal, 2013; American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2013; Clinical Obesity, 2014

Insulin resistance.

When you eat a lot of high-sugar meals — donuts for breakfast, anyone? — it can increase your body's demand for insulin, a hormone that helps your body convert food into usable energy. But when insulin levels remain high, your body becomes less sensitive to the hormone, and glucose builds up in the blood.

Scientists can quickly induce insulin-resistance in rats by feeding them diets that are abnormally high in sugar.

Symptoms of insulin resistance can include fatigue, hunger, brain fog, and high blood pressure. It's also associated with extra weight around your midsection. Still, most people don't realize they're insulin-resistant until they develop full-blown diabetes — a much more serious diagnosis.

Source: Hypertension, 1987; The American Journal of Cardiology, 1999; American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2002; Nutrition & Metabolism, 2005

Diabetes.

Between 1988 and 2008, the prevalence of diabetes in America increased by 128%. Today diabetes affects about 25 million people in the US — or 8.3% of the population. Countries with higher sugar intake face higher rates of diabetes.

One study that followed 51,603 women between 1991 and 1999 found an increased risk of diabetes among those who consumed more sugar-sweetened beverages — including soda, sweetened ice tea, energy drinks, etc. And a massive review of prior studies involving 310,819 participants supported the same result, concluding that drinking lots of soda was associated not just with weight gain but with the development of type 2 diabetes.

The American Diabetes Association, while it recommends that people avoid soda and sports drinks, is quick to point out that diabetes is a complex disease, and there's not enough evidence to say that eating sugar is the direct cause. But both weight gain and sugary drinks are associated with a heightened risk.

Portions seem to be crucial when it comes to sugar and diabetes. A 2013 study of eating habits and diabetes prevalence in 175 countries concluded the following: "Duration and degree of sugar exposure correlated significantly with diabetes prevalence ... while declines in sugar exposure correlated with significant subsequent declines in diabetes rates" — even after controlling for other social, economic, and dietary factors.

Source: JAMA, 2004; Diabetes Care, 2010; PLOS ONE, 2013; BMC Public Health, 2014; American Diabetes Association

Obesity.

Obesity is one of the most-cited risks of excess sugar consumption. Just one can of soda each day could lead to 15 pounds of weight gain in a single year, and each can of soda increases the odds of becoming obese, a JAMA study noted.

While it's possible that drinking soda is harmful — above and beyond other sugary foods — the relationship is complex: If people who drink soda don't consume more calories overall, that might not hold true. But too many "empty" calories often leads to over-consumption in general.

Sugar might directly raise the risk of obesity, but the association could be tied to diabetes, metabolic syndrome, or habits (e.g. diet and exercise) associated with high-sugar diets.

"The complexity of our food supply and of dietary intake behavior, and how diet relates to other behaviors, makes the acquisition of clear and consistent scientific data on ... obesity risk especially elusive," concluded one review.

But a more recent study cautioned, "we should avoid the trap of waiting for absolute proof before allowing public health action to be taken."

Source: American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2004; JAMA, 2004; International Journal of Obesity, 2006; Obesity Reviews, 2013; Nutrition Reviews, 2014

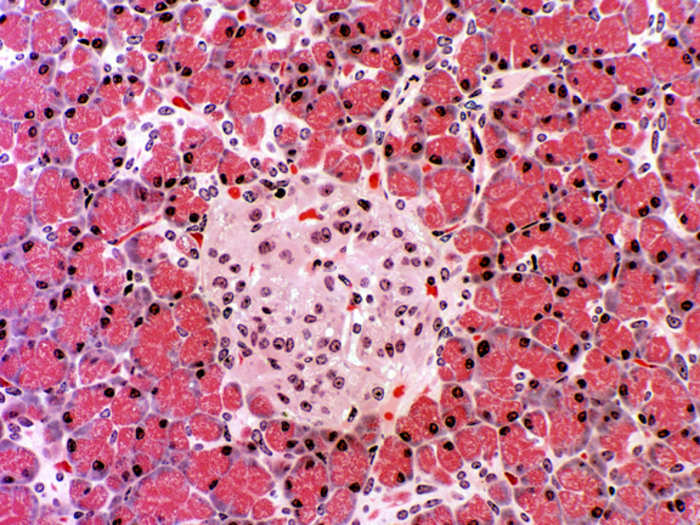

Liver failure.

High doses of sugar can make the liver go into overdrive: The way our bodies metabolize fructose can stress out and inflame the organ. That's one reason excess fructose is called a "key player" in the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, where fat accumulates throughout the liver.

People with this diagnosis usually drink two times more soda than the average person. Still, the research is "unresolved" on whether sugar specifically is a culprit, or if it's the weight gain that typically comes with eating too much sugar.

Most people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease see few complications and often don't realize they have it. But in some people, the accumulated fat can lead to scarring in the liver and eventually progress to liver failure.

Source: Journal of Hepatology, 2007; Journal of Hepatology, 2008; World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2013; Nutrients, 2014

Pancreatic cancer.

Some studies have linked high-sugar diets with a slightly elevated risk of pancreatic cancer — one of the deadliest forms of the disease. The link may be because high-sugar diets are associated with obesity and diabetes, both of which increase the likelihood someone will develop pancreatic cancer.

At least one large study, published in the International Journal of Cancer, disputed the link between increased sugar intake and increased cancer risk, so more research is needed.

Source: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 2002; The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2006; Annals of Oncology, 2012; International Journal of Cancer, 2012; Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity, 2012; BMJ, 2014

Kidney disease.

The idea that a high-sugar diet — and too much soda in particular — may be a risk factor for kidney disease is still just a hypothesis, but there's some reason for concern.

"Findings suggest that sugary soda consumption may be associated with kidney damage," concluded one study of 9,358 adults. (The association emerged only in those drinking two or more sodas a day.) And in 2014, a large analysis of previous research on the topic supported the same finding, suggesting a strong association between drinking too much soda and developing kidney disease.

We also know a little more through highly controlled studies of rats. Rats fed extremely high-sugar diets — equivalent to 12 times the sugar in the WHO's guidelines — developed enlarged kidneys and poor kidney function.

Source: PLOS ONE, 2008; Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 2010; Renal Physiology, 2011; Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease, 2013; Nephrology, 2014

High blood pressure.

Salty foods usually get a bad rap for causing hypertension, or high blood pressure, but eating lots of sugar is also linked to high blood pressure. One team of researchers even went so far as to suggest we're all focused on "the wrong white crystals."

When it comes to addressing hypertension, they wrote, "it is time for guideline committees to shift focus away from salt and focus greater attention to the likely more-consequential food additive: sugar."

In one study following 4,528 adults without a history of hypertension, consuming 74 or more grams of sugar each day was strongly associated with an elevated risk of high blood pressure. A recent review also backs up the worrisome association between high-sugar diets and high blood pressure.

And in another (very) small study that followed 15 people, researchers found drinking 60 grams of fructose led to a spike in blood pressure two hours later. This response may be because digesting fructose produces uric acid, a chemical linked to high blood pressure. Yet as one meta-analysis of the data concluded, "longer and larger trials are needed."

Source: Hypertension, 2001; American Journal of Physiology, 2008; Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 2010; Hypertension, 2012; Hypertension, 2012; Open Heart, 2014; British Journal of Nutrition, 2015

Heart disease.

Heart disease is the number-one killer in the US. Smoking and a sedentary lifestyle are known to be major risk factors, but conditions associated with excess sugar consumption, like diabetes and being overweight, are also known risk factors for heart disease.

Recent research suggests that eating too much sugar might stack the odds against your heart health, especially if you're a woman.

In one study of rats with high blood pressure — which may offer clues for future research but can't be directly extrapolated to humans — those fed high-sugar diets saw heart failure sooner compared than rats fed high-starch or high-fat diets.

And a CDC study of 11,733 adults concluded that there is "a significant relationship between added sugar consumption and increased risk for [heart disease] mortality." When participants got 17% to 21% of their daily calories from sugar, they were 38% more likely to die from heart disease than those who limited their calories from sugar to 8% of their total caloric intake.

Source: Journal of Hypertension, 2008; American Journal of Cardiology, 2012; JAMA Internal Medicine, 2014

Addiction (sort of).

Most doctors don't think the "food addiction" you read about in diet books is a real thing, and it's certainly distinct from drug or alcohol addiction. But there is evidence that rats can become dependent on sugar, which hints that similar behavior is possible in humans.

"In some circumstances, intermittent access to sugar can lead to ... changes that resemble the effects of a substance of abuse," according to one study, in which sugar-addled rats displayed bingeing, craving, and withdrawal behaviors.

In fact, when people are in withdrawal from opioids like heroin, they tend to eat more sugary foods, possibly "to replace the action of opiates in the brain," researchers have hypothesized.

It may be simpler than that, though: One recent paper suggested that people are addicted to the habit of eating foods they think are especially tasty, not any particular food itself — sugary or otherwise.

Source: Obesity, 2002; Behavioral Neuroscience, 2005; Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 2007; Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 2008; Appetite, 2011; Nutrition, 2014; Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 2014

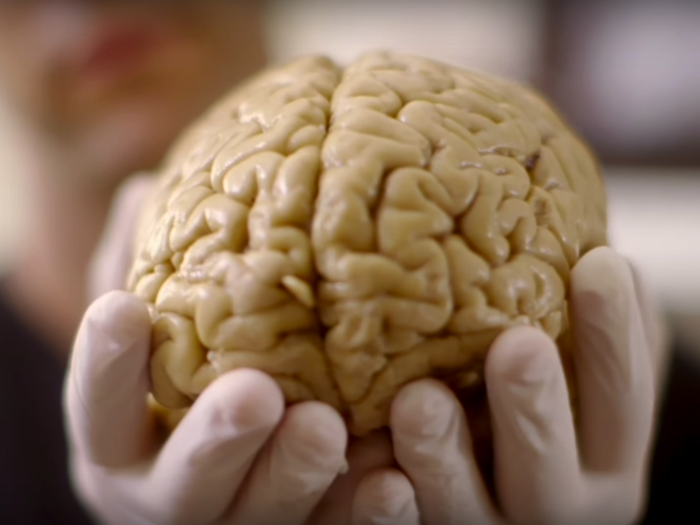

Cognitive decline.

Obesity and diabetes are both tied to cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease, so it's no surprise that new studies are finding a link between excess sugar and these brain conditions.

Yet reasons for a possible relationship between a high-sugar diet and dementia later in life are unclear. Is it tied to diet? Or is the real link only between diabetes and Alzheimer's?

Rats fed a diet high in fat and sugar in one recent study had impaired memory and dulled emotional arousal. And another study in humans found an association between eating a lot of fat and simple carbohydrates (including sugar) and reduced performance in the hippocampus — a brain structure crucial to memory.

There are many other open questions about sugar and cognitive decline, with some researchers urging caution until they can round up more and better evidence.

Source: American Journal of Alzheimer's, 2009; Journal of Gerontology, 2010; Behavioral Neuroscience, 2011; Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 2013;Nutrition Journal, 2013; Behavioral Neuroscience, 2013; Progress in Neurobiology, 2014

Nutritional deficiencies.

If you're scarfing down lots of excess sugar, you're probably skipping over the things you should be eating instead.

"High-sugar foods displace whole foods (eg, soft drinks displace milk and juice consumption in children) and contribute to nutritional deficiencies," according to a statement released by the American Heart Association (AHA). American children, for example, eat too many calories — especially sugar — but don't get enough Vitamin D, calcium, or potassium.

Those deficiencies can lead to symptoms like fatigue, brittle bones, and muscle weakness.

In a study of 568 10-year-olds, as sugar intake increased, levels of essential nutrients decreased. And in a 1999 study, researchers from the Department of Agriculture found that when people got 18% or more of their calories from sugar, they had the lowest levels of essentials like folate, calcium, iron, Vitamin A, and Vitamin C.

Source: Family Economics and Nutrition Review, 1999; Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 1998; Circulation, 2002; American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2003; Nutrients, 2014

Gout.

Gout used to be a painful disease limited to the rich. Our diets have changed, though, and this excruciating form of arthritis has become more common across all sectors of society.

Organ meats, anchovies, and other foods associated with gout contain high levels of purines. Purines are chemicals that produce uric acid when the body breaks them down, and a buildup of uric acid is what often leads to gout.

But uric acid is also a byproduct of sugar metabolization, and newer research suggests that too much sugar could be a risk factor for gout, too. "Consumption of sugar sweetened soft drinks and fructose is strongly associated with an increased risk of gout in men," concluded a 2008 study that tracked thousands of patients for more than a decade.

The evidence is now strong enough to "recommend reduction of [soda] consumption ... to reduce the burden of gout" among high-risk populations, researchers concluded in 2014.

Source: British Medical Journal, 2008; Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease, 2012; Pacific Health Dialog, 2014

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement