The rise and fall and rise again — of Abercrombie & Fitch

Avery Hartmans

- Abercrombie & Fitch was founded as a store for outdoor gear in the late 1800s.

- It became hugely popular with 2000s teens until changing tastes and controversy sent it into decline.

If you were a teen in the 2000s, chances are you either shopped at Abercrombie & Fitch or felt too excluded to set foot in the store.

The 130-year-old retailer may have gotten its start catering to fishing and hunting enthusiasts, but by the late 1990s, the brand bore little resemblance to its outdoorsy origins. Its dimly lit, heavily scented stores — known primarily for their shirtless male models and narrow range of sizes — presented a brand of cool that seemed off-limits to anyone who wasn't thin, white, and well-off.

While Abercrombie may once have been the epitome of a certain form of cool, the brand fell on hard times in the 2010s due a mix of changing public sentiment and numerous controversies and lawsuits, including one that went all the way to the Supreme Court.

In recent years, the brand has seen a resurgence in popularity thanks to a new, more inclusive image: it revamped its stores, expanded its size range, and made its pricing more approachable. Plus, its offerings have become almost irresistibly stylish, standing out even in the era of fast-fashion brands clamoring for Gen Z's attention.

Here's how Abercrombie & Fitch rose to fame, almost lost it all, then mounted a comeback.

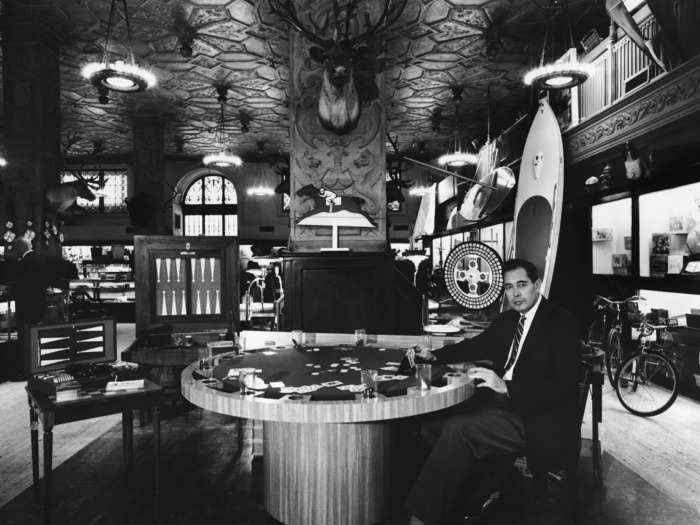

Abercrombie Co. was founded in 1892 as an outdoor retailer.

Founder David Abercrombie opened the original Abercrombie store to sell camping, fishing, and hunting gear.

In 1904, a lawyer named Ezra Fitch purchased a large share of the company and was named co-founder — the company became Abercrombie & Fitch.

By 1910, David Abercrombie had left, and the company had opened a large department store.

The 12-story department store on Madison Avenue sold both men's and women's clothing, in addition to housing a shooting range and golf school. Abercrombie & Fitch also started a mail-order catalog, mailing out 50,000 copies to consumers.

According to the Netflix documentary "White Hot: The Rise & Fall of Abercrombie & Fitch," the brand's reputation in the early 1900s was as a store for stuffy, WASP-y sportsmen. Amelia Earhart and Theodore Roosevelt wore Abercrombie, and when aviator Charles Lindbergh made the first solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927, he wore Abercrombie too.

In a 1931 issue of The New Yorker, author E.B. White wrote that Abercrombie had "the most gaped-at window in town. Displays all the clothes men want to wear all the time and don't."

Abercrombie survived the Great Depression and continued to grow, expanding to new states. But by the middle of the century, sales had slumped. Abercrombie filed for bankruptcy in 1977.

In 1978, the brand was acquired by Oshman's Sporting Goods, a Texas-based retailer.

A decade later, it was sold to Limited Brands — now known as simply L Brands — the retail conglomerate run by Leslie Wexner. Wexner was widely considered a retailing genius and called "the Merlin of the Mall" due to his success at building chains like The Limited, Victoria's Secret, and Bath & Body Works. (Wexner has since cut ties with L Brands and has been scrutinized for his relationship with Jeffrey Epstein.)

After being acquired by L Brands, Abercrombie moved its headquarters from New York to Ohio where it built a massive campus complete with a fake retail store, according to "White Hot."

In the 1990s, Wexner hired Mike Jeffries as CEO of Abercrombie and tasked him with building the brand as it came to be known in its early-2000s heyday.

Jeffries turned his attention to cornering the teen retail market, making it the brand's mission to appeal to American teens.

"We knew we wanted to be the coolest brand for the 18 to 22-year-olds," Cindy Smith-Maglione, the former vice president of merchandising, said in "White Hot."

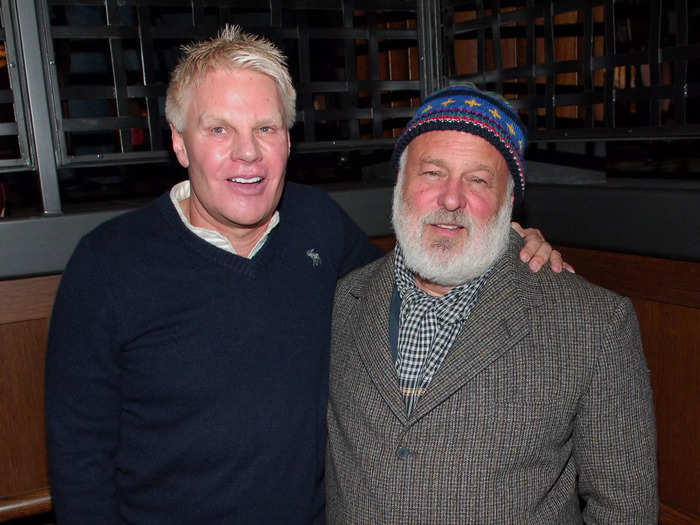

Abercrombie hired fashion photographer Bruce Weber to shoot ad campaigns and store photos, and it's his aesthetic that defined the company's brand in the '90s and 2000s.

Jeffries' formula for success mixed sex appeal — particularly male sex appeal — with the brand's century-old heritage. And the formula worked.

The Abercrombie look married preppy separates with the overt sexiness popular in the late '90s and early 2000s: Skirts were short, jeans were low-rise, and tank tops were tight, but everything was portrayed as "all-American," a particular obsession of Jeffries', according to the "White Hot" documentary.

In the Weber-shot ad campaigns, male models were often photographed shirtless, either alone or in groups, while female models were often relegated to supporting roles. In the early days, nearly everyone was white.

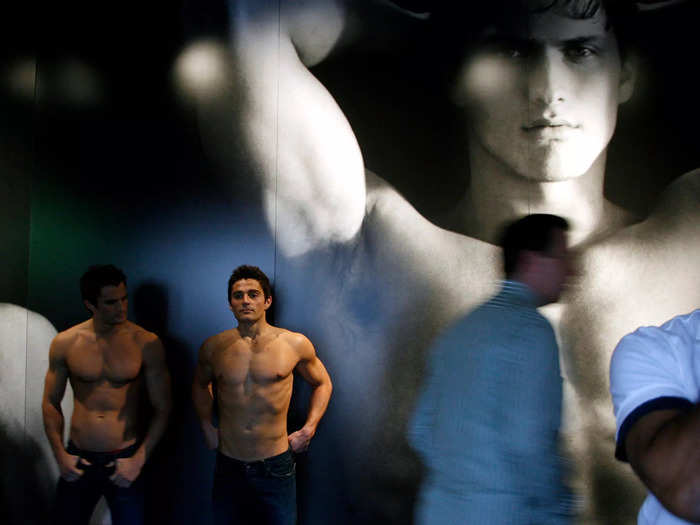

Abercrombie's stores were a central component to the image the brand was looking to sell.

Abercrombie stores weren't like any other mall brand. Rather than showcase its offerings on mannequins in store windows, Abercrombie covered the windows with shutters and displayed only a large photo of an Abercrombie model at the entrance — if shoppers wanted to see what the brand offered, they'd have to come inside. At many stores, shirtless male employees would greet shoppers as they entered.

Once in the store, shoppers were greeted with dim lighting, loud music, and the overwhelming scent of the brand's "Fierce" cologne.

"Every piece of Abercrombie was by design, by Mike's design. The stores, the product, the whole thing, he would sign off on," Smith-Maglione, the former merchandising vice president, said in "White Hot."

Abercrombie went public on the New York Stock Exchange in 1996.

When Jeffries took over, Abercrombie & Fitch had 36 stores and was doing $50 million in sales. By 1996, the company had about 125 stores and $335 million in sales, Bloomberg reported.

Two years later, Abercrombie launched its childrens' brand, and in 2000, the company opened its subsidiary, Hollister, which catered to teens but with a California-inspired influence.

Abercrombie was everywhere, and as of 1999, was a certified cultural phenomenon thanks to the song "Summer Girls" by LFO: "I like girls that wear Abercrombie & Fitch," the lyrics went. "I'd take her if I had one wish."

But by 2002, some cracks began to show in Abercrombie's armor when the brand was accused of racism and discrimination over its product assortment.

Following the release of multiple racist t-shirts depicting Asian stereotypes, Asian Americans across the US protested outside Abercrombie stores, demanding that the brand stop selling the graphic tees.

In response, the company pulled the products from its shelves and burned them, according to "White Hot."

But t-shirts were just the beginning: a year later, Abercrombie was under fire over its hiring practices.

In 2003, a group of former and prospective employees filed a class-action lawsuit against Abercrombie, claiming that the company refused to hire them or fired them on the basis of their race.

According to "White Hot," Abercrombie had a handbook that dictated what employees should look like down to their underwear, jewelry, and hair. The handbook prohibited dreadlocks and gold chains and mandated a look Abercrombie described as "natural," "American," and "classic."

Former employees said in the documentary that corporate dictated that store staff be attractive and often valued looks over abilities. When Jeffries, the CEO, would make unannounced store visits — known as "blitzes" — the stores would try to ensure that their best-looking employees were working that day, even keeping some workers on staff just for those visits.

Abercrombie settled the class-action suit in 2004 without admitting any wrongdoing. It agreed to pay more than $40 million and signed a consent decree agreeing to change its hiring practices and hire a chief diversity officer.

Abercrombie was sued again in 2012 after a pilot claimed Jeffries had some unusual requests for staff aboard his private jet.

In 2012, an age discrimination suit filed by a former pilot revealed the "Aircraft Standards" for Abercrombie's executive jet.

The pilot claimed that crew were required to wear Abercrombie polo shirts, sandals, and underwear, and that men had to wear the retailer's famous cologne. Staff were also required to wear black gloves when handling silverware and white gloves when setting the table; had to answer every question and request with "no problem"; and had to play a specific song for passengers on return flights.

Abercrombie settled the pilot's suit without admitting fault.

Around the same time, Jeffries was in hot water over comments he'd made years earlier where he openly admitted to Abercrombie intentionally excluding certain consumers.

Jeffries said in a 2006 interview with Salon that Abercrombie made clothes for the "cool kids."

"In every school there are the cool and popular kids, and then there are the not-so-cool kids," he told Salon. "Candidly, we go after the cool kids. We go after the attractive all-American kid with a great attitude and a lot of friends. A lot of people don't belong [in our clothes], and they can't belong. Are we exclusionary? Absolutely."

Jeffries added that the store only hired good-looking people because they "attract other good-looking people."

But it wasn't until 2013 that those comments went viral, sparking boycotts and petitions and forcing Jeffries to publish a semi-apology.

"While I believe this 7-year-old, resurrected quote has been taken out of context, I sincerely regret that my choice of words was interpreted in a manner that has caused offense," he wrote in a Facebook post.

That same year, the brand finally began to offer larger sizes.

But by that time, Abercrombie's sales were already beginning to wane.

By 2014, same-store sales had declined for 11 straight quarters. Two subsidiary brands, Ruehl 248 and Gilly Hicks, were shut down only a few years after launch, and Abercrombie had begun shuttering some of its mall stores. (Gilly Hicks was later resurrected and still exists today.)

The slow sales were due in part to the company's controversies, but also due to shifts among the younger demographic. Teens had grown tired of logo t-shirts and hoodies and started opting for cheaper, fast-fashion brands like Forever 21. Nike took over as teens' aspirational brand.

At the same time, the power of the mall was beginning to shrink: by 2014, the number of teens visiting malls had dropped by 30% compared to the early 2000s.

Abercrombie became embroiled in another lawsuit in the late 2000s that would make it all the way to the Supreme Court.

In 2008, an Oklahoma teen named Samantha Elauf applied for a job at her local Abercrombie store and was recommended for hire. But the store later said it couldn't hire her because she wore a black headscarf, which the company said violated its policy that salespeople couldn't wear caps at work.

In response, Elauf, a Muslim, filed a religious-discrimination lawsuit. While Abercrombie had settled other lawsuits in the past, this time, it dug its heels in and allowed the case to make it all the way to the Supreme Court.

In 2015, the court ruled 8-1 against Abercrombie. Its opinion stated that religion was a protected characteristic and must be accommodated.

In late 2014, Jeffries retired as Abercrombie's CEO.

Jeffries retired with an exit package worth $27 million.

"It has been an honor to lead this extraordinarily talented group of people," Jeffries said in a statement at the time. "I believe now is the right time for new leadership to take the company forward in the next phase of its development."

A committee formed by three senior executives and the Abercrombie board chairman managed the company until a successor could be selected.

Following Jeffries' departure, Abercrombie attempted to shift away from its sex-heavy, logo-heavy past.

The company decided to phase out large logos, replacing them with smaller, more subtle designs and putting leftover logo apparel on clearance.

In 2015, Abercrombie got rid of its shirtless male greeters and overhauled its appearance policies for sales clerks, though there were still some rules in place, including "no extreme make-up or jewelry."

Also gone were the dimly lit stores and pulsating music — the stores became brighter and free of the overpowering scent of cologne.

Even the ubiquitous shopping bags, which featured a bare male torso, were nixed in favor of a subtler logo bag.

Fran Horowitz took over as CEO in 2017.

Horowitz had joined Abercrombie in 2014 from Ann Taylor Loft, working as brand president of Hollister and as president and chief merchandising officer for Abercrombie & Fitch.

Under Horowitz, sales began to improve. Abercrombie closed down unprofitable locations while investing in stores that worked. Between 2010 and the 2018 fiscal year, the company closed 450 stores and remodeled others in an effort to reconnect with consumers.

Abercrombie also refocused design and marketing, shifting toward a more mature look and nixing the brand's super-preppy aesthetic. The company also began targeting consumers between 18 to 25 rather than young teens.

By the end of 2018, with improved sales and a new aesthetic, the brand was ready for a comeback.

In November 2018, Abercrombie was on a positive trajectory, reporting its fourth consecutive quarter of positive same-store sales growth that sent its shares soaring.

The brand closed 40 stores — mostly its kids stores — while planning to open 40 new locations with a more boutique-like feel.

But it was the clothes that really stood out: Abercrombie had started offering similar styles and trends to higher-end brands like Reformation at a much more affordable price point. The product assortment became "more sophisticated, is more on-trend, and better reflects what modern consumers want," Neil Saunders, managing director of GlobalData Retail, wrote in a note to clients at the time.

That year, Abercrombie exceeded $1 billion in annual digital sales for the first time in its history, according to the company.

"We are not the Abercrombie & Fitch that you once knew," Horowitz said during investor day that April.

Like other retailers, the pandemic brought about change and uncertainty for Abercrombie, but the brand outperformed.

Abercrombie saw a 43% increase in digital net sales in 2020, despite the challenges of the pandemic. The company credited that success to data analytics and learning more about their customers' needs, even during a time when the apparel industry was in a state of upheaval.

That strong performance continued in 2021, despite the inventory delays many retailers experienced, particularly over the holiday season. In its full-year results posted in March 2022, Abercrombie reported $3.7 billion in net sales.

But like many other apparel brands, Abercrombie is now being pummeled by inflation.

Abercrombie recently posted second-quarter results that showed that the brand is seeing the impacts of inflation, which has caused shoppers, especially lower-income shoppers, to buy less apparel.

Though Abercrombie delivered its highest second-quarter sales since 2015, Hollister saw "a greater than anticipated impact from inflation" that resulted in low conversion and smaller basket sizes, Horowitz said in a statement. Abercrombie lowered its sales outlook for the remainder of the year, causing shares to drop sharply.

But Abercrombie isn't alone: other retailers — including Gap, Macy's, and Nordstrom — reported similar uncertainty surrounding the months ahead during their most recent earnings. While Abercrombie has had a stand-out few years and a successful turnaround, its future could be impacted by factors outside its control.

Matthew Wilson contributed to an earlier version of this article.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement