Levi's got its start making clothes for cowboys now it's a Gen Z status symbol. Here's how the 169-year-old retailer became the world's most iconic denim company.

Avery Hartmans

- Levi's didn't invent denim, but it did invent blue jeans as we know them today.

- The 169-year-old retailer has weathered world wars, the Great Depression, and the cyclical nature of fashion.

Levi Strauss was born in Bavaria in 1829.

Strauss immigrated to the US in 1847. He landed in New York City and joined his half-brothers' dry-goods business.

Six years later, Strauss headed west, moving to San Francisco to open a West Coast branch of the business, selling items like clothing and blankets to general stores, according to Levi's.

Jeans as we know them today were born decades later when Strauss teamed up with a tailor to create riveted pants.

In the early 1870s, a customer of Strauss', a tailor named Jacob Davis, came up with the idea to use copper rivets to strengthen pants.

He purchased fabric from Strauss and made button-fly pants, which were such a hit among customers, he decided to patent them. He asked Strauss to join him on the patent, which was granted in 1873.

The pants were akin to modern-day Levi 501s — back then, the model was called "XX" — and featured a single back pocket, a watch pocket, and suspender buttons.

Modern-day jeans were born, though at the time, they were called "waist overalls" or simply "overalls." It wasn't until the 1960s that Strauss' creation was nicknamed "jeans," according to Levi's. The name comes from the French word "Gênes," meaning Genoa, an Italian port city where sailors often dressed in denim, Vice reports.

In 1886, Levi's started including a leather patch on its clothing containing a logo with two horses, a logo that's still used today.

Over time, the original design of the jeans changed slightly: a second back pocket was added in 1901, and belt loops were added in 1922.

In 1937, in response to customer requests, the pants' trademark back-pocket rivets were covered up to make sitting down more comfortable and to keep them from scratching saddles and upholstery, according to Levi's.

But some Levi's products made during the 1880s bore a troubling reminder of a dark period in US history.

In the 1880s, the US government passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, a law aimed at banning Chinese workers from immigrating to the US. The law came during a period of anti-Chinese sentiment following the Gold Rush and the construction of the railroads.

Though the law was later repealed — and eventually condemned — Levi's briefly adopted its own anti-Chinese labor policy: a tagline included in its products and its ads that read "made by white labor," The Wall Street Journal reports.

A company spokesperson recently told the Journal that today, Levi's is "wholly committed to using our platform and our voice to advocate for real equality and to fight against racism in all its forms."

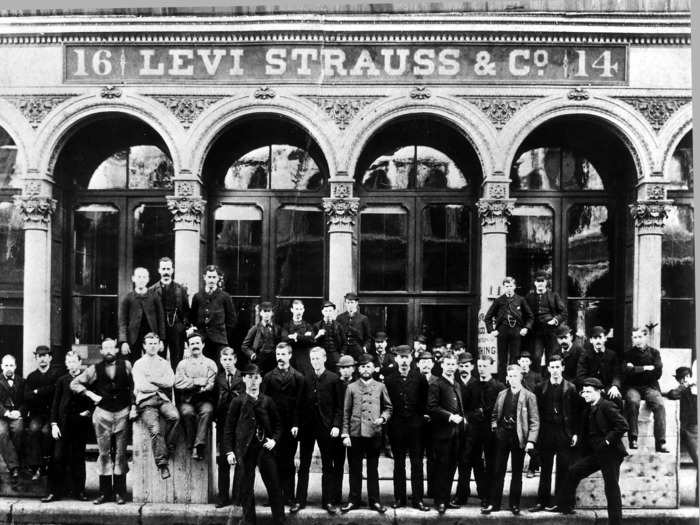

Throughout the early 1900s, Levi's maintained a reputation as the clothing of choice for laborers and cowboys, an image it leaned into following the Great Depression.

Post-Depression, Levi's made a big play for cowboys' wallets, taking out ads in agricultural papers that served the Western states, publications like "Washington Farmer" and "The Arizona Producer."

But when World War II began, Levi's shifted gears, sending jeans overseas at the request of the US Navy. At the same time, women working in US factories and shipyards started wearing Levi's, since they protected them from hazards like welding sparks, according to Levi's.

By 1950, Levi's had produced 95 million pairs of jeans, which at that time cost only $3.50, according to Time.

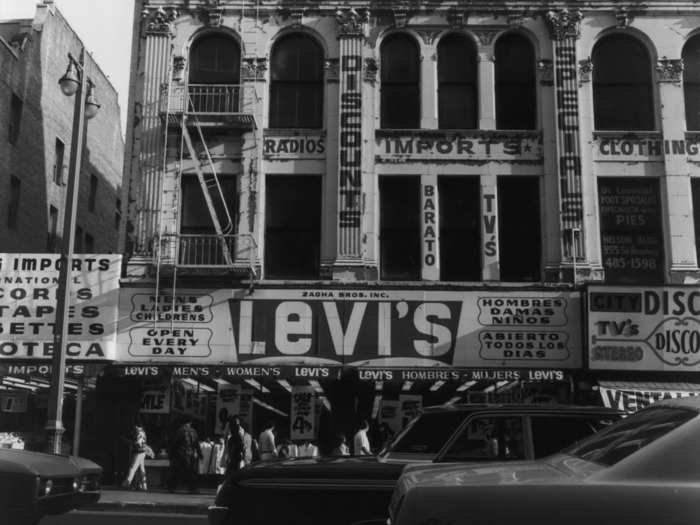

The 1960s and '70s ushered in a renaissance in American fashion, which further spurred demand for Levi's in the US and abroad.

As more casual clothing styles took hold in the middle of the century, blue jeans became more mainstream. Civil rights leaders wore blue jeans, hippies wore blue jeans, and rock bands wore blue jeans. In fact, bands like Jefferson Airplane were making radio commercials for Levi's in the late 1960s.

In the US, denim became synonymous with equality and freedom, art historian Caroline A. Jones told Smithsonian Magazine in 2020.

"Youth activists ... used denim as an equalizer between the sexes and an identifier between social classes," she said.

But shifts were happening overseas, too. In East Germany during the Cold War, items like jeans were seen as "symbols of freedom, of independence, of being cool," German historian Gerd Horten previously told Insider.

Since sales of Levi's were banned in East Germany in the 1960s, a black market for the pants sprung up, with jeans going for as much as $500 a pop.

But by the late 1970s, East Germany's economy was crumbling and the government relented, requesting that Levi's ship nearly 800,000 pairs of jeans ahead of the holidays. Young Germans lined up to buy the denim, which cost 149 East German marks, equal to about $74 US at the time.

In the early 1990s, Levi's helped usher in the concept of casual Fridays, part of a play to help boost its khaki brand, Dockers.

Though casual Fridays date back to a Hewlett-Packard initiative from the 1950s, we have Levi's and its khaki brand, Dockers, to thank for them becoming mainstream, according to a 2014 Insider article.

The early 1990s was a tough time for the apparel industry, and it was also likely a tough time for HR departments across the country: Though casual Fridays had become the norm, there was no clear code for what that meant — many workers saw it as an opportunity to dress sloppily or inappropriately.

Levi's saw an opportunity, and in 1992, released a pamphlet titled "A Guide to Casual Businesswear." It gave examples of how to dress for the workplace – mainly Dockers khakis and Levi's jeans – and offered tips and advice for what counted as "business casual."

"We did not create casual business wear," Daniel Chew, Levi's former consumer marketing director for North America, told Bloomberg Businessweek in 1996. "What we did was identify a trend and see a business opportunity."

The pamphlet attracted the attention of major US companies — Charles Schwab distributed it to employees — and by 1995, Levi's posted then-record sales of $6.7 billion, a 10% increase from the year prior, according to Bloomberg.

Levi's outfitted the US Olympic team during the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles.

The company aired an ad campaign for its 501 jeans at the games, which led to a surge in sales, according to Levi's.

One year later, Levi's, which had gone public in 1971, went private again in a leveraged buyout led by Levi Strauss' descendants. The buyout, valued at $1.7 billion, was the largest of its kind at the time.

But by the late 1990s, demand for Levi's started to wane.

In 1997, Levi's announced that it would close 11 manufacturing plants and lay off about 6,400 employees, about 34% of its workforce.

"In the 1960s, '70s and '80s, we were chasing demand and couldn't produce fast enough," company spokesman Gavin Power told the Los Angeles Times at the time. "It's not like that anymore."

Though Levi's was the largest brand-name apparel-maker at the time, it was facing several challenges: spending on apparel had dropped 3% in the '90s compared with the '80s; manufacturing advancements meant more clothes could be produced by fewer people; and competition was heating up, thanks to brands like Ralph Lauren and cheaper private labels at department stores.

"A lot of people can buy jeans for less than Levi's is offering them at and get the same quality," retail consultant Kurt Barnard told the Times in 1997.

Sales continued to decline for the next decade, but by 2007, Levi's was once again profitable.

Five years later, Levi's purchased the naming rights to the new San Francisco 49ers stadium.

Levi's agreed to pay the NFL team $220 million over 11 years in what was, at the time, the third-biggest naming-rights deal in the nation.

In 2019, Levi's filed to go public once again, at a $6.6 billion valuation.

In honor of the occasion, the famously strict New York Stock Exchange relaxed its "no blue jeans allowed" policy so that everyone on the trading floor could wear jeans and denim jackets — even floor traders and stock exchange employees were fitted for Levi's apparel in advance.

CNBC's Bob Pisani said at the time that the trading floor at the NYSE looked like "Woodstock '69."

The onset of the pandemic in 2020 hurt Levi's sales. Industry experts began predicting the end of jeans as people remained at home, ensconced in loungewear.

The pandemic hit retailers hard, and Levi's was no exception. The brand temporarily shut down its stores, faced supply chain challenges, and saw a decline in sales as consumers opted for elastic waistbands over "hard pants."

By May 2020, net revenue had plummeted 62% year-over-year as costs surged due to the pandemic. In July of that year, Levi's laid off 700 workers, equivalent to 15% of its workforce.

By 2021, losses began to shrink, but sales were still down. CEO Chip Bergh acknowledged that "changes look like they're here to stay," including the lingering "casualization" of fashion.

Still, there were a few bright spots for Levi's. Fluctuations in body weight during the pandemic helped fuel sales in 2021, Bergh said at the time. Plus, the company dipped a toe in activewear and loungewear with its acquisition of yoga apparel brand Beyond Yoga.

And while Levi's has long been a sustainability-minded company, it's ramped up its efforts in recent years, urging consumers to "buy better, wear longer" and aiming to become a net-zero emissions firm by 2050.

Meanwhile, Levi's has become the go-to choice for models, musicians, and the fashion crowd.

While pricey denim was all the rage in the early aughts, trends shifted in the 2010s in favor of reasonably priced Levi's.

"To me, the backlash — or 'denim fatigue' — is because all of the jeans [on the market] look exactly alike," Sean Barron, cofounder of denim brand Re/Done, told Fashionista in 2015. "They're all skinny with stretchy blue fabric. For a while it was like, 'what else can I buy?' These brands are making people look homogeneous."

Meanwhile, Levi's has kept selling its classic styles, including the relaxed-fit 505 and the more rigid, straight-leg 501, a classic style that hasn't changed much since the 1800s — it's "the ultimate original jean," as trend forecaster Samuel Trotman told fashion site High Snobiety.

And it's not just full-length jeans that have become a must-have item: as music festivals became a popular destination, sales of 501 cutoffs skyrocketed.

"We again dominated Coachella as the go-to uniform for festival season with Levi's 501 cutoff shorts, which were up more than 50% this quarter, taking center stage," CEO Charles Bergh said during the company's second-quarter earnings call in 2019.

But it's vintage Levi's that have achieved almost Holy Grail status among the fashion-forward and eco-conscious shoppers of younger generations.

Rather than shelling out for brand-new jeans, Gen Z and millennial shoppers are scouring thrift stores and internet marketplaces for vintage Levi's. Finding the perfect pair has been elevated to an artform, with everyone from GQ to InStyle creating guides to help shoppers identify whether something's actually vintage and navigate Levi's notoriously tricky sizing.

Levi's itself caught on to the trend, launching its own secondhand shop in 2020 and hiring a slate of celebrities and tastemakers, including Hailey Bieber and Jaden Smith, to promote it.

Super-vintage Levi's — as in, from the 1800s — are viewed almost reverently by collectors. Case in point: one of the oldest known pairs of Levi's recently sold for $76,000 at auction.

The pants, found in an old mine several years ago, have a single back pocket, suspender buttons at the waist, and show a few signs of their age, including some small holes and candle-wax marks. Still, they are considered to be in "good/wearable" condition.

Still, like many retailers, Levi's is growing wary of the months ahead as inflation and fears of a recession scare off shoppers.

Levi's recently cut its full-year profit forecast after falling short on third-quarter revenue as cautious consumers cut back on spending.

The company has also experienced some executive changes in recent months: its president departed the company early this year after advocating against pandemic school closings and mask mandates. Levi's recently named a new president: Michelle Gass, the top executive at Kohl's, will join Levi's and eventually succeed the brand's longtime CEO, Chip Bergh.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement