Inside the shameful history of the 'Lavender Scare,' when the US government embarked on an anti-gay witch hunt and purged thousands of employees

James Pasley

- In the 1950s, the US government launched a campaign focused on finding and purging gay government employees.

- It was prompted due to a misguided idea that gay people were vulnerable to blackmail and considered easy targets for Russia.

"It was a witch hunt," former Navy Lieutenant Joan Cassidy described the decades-long government campaign which later became now known as the "Lavender Scare."

Cassidy was one of up to 10,000 government employees who were fired because of their sexuality in the 1950s and 60s. During the Cold War paranoia of the late 1940s and 50s, the US government famously led a witch hunt targeting communists leading to a hysteria dubbed the "Red Scare."

The hysteria was later followed by a second government campaign prompted by discrimination against gay people in the federal government, which similarly became known as the "Lavender Scare."

The focus of the Lavender Scare was finding and purging gay government employees. According to the National Archives, its impact was actually greater and longer lasting than the Red Scare.

Sources: Guardian, ABC News, National Archives

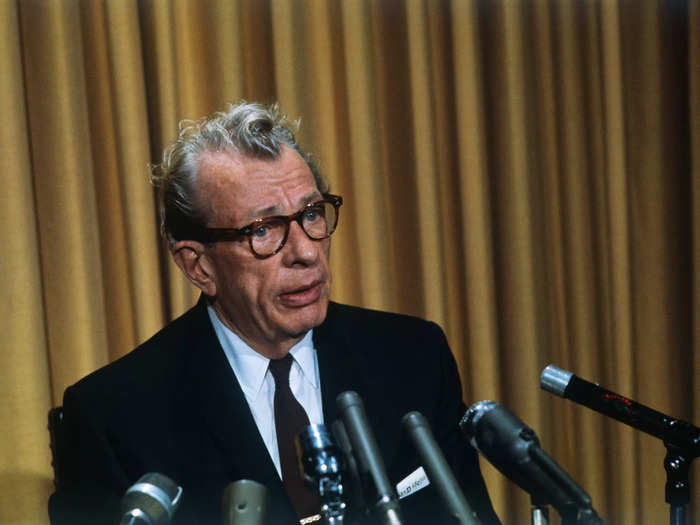

Lavender is a color often associated with the queer community. Back then, certain newspapers and politicians, including Republican Sen. Everett Dirksen, called gay men "lavender lads."

Source: History.com

The campaign began in the late 1940s. As the public's general awareness of homosexuality increased, discrimination against the community was on the rise, including within the US government.

In 1946, after noting its security concerns, a US Senate committee gave broad new powers to the US Secretary of State to dismiss employees to protect national security.

The following year, the US Park Police started arresting and intimidating gay men under what was called a "Sex Perversion Elimination Program."

Then, in 1948, Congress passed a law that labeled gay and lesbian people mentally ill and allowed police to arrest them.

Source: National Archives

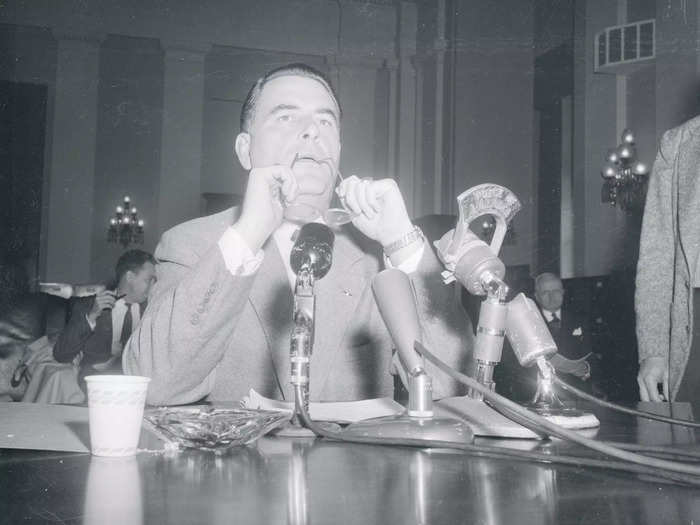

In 1950, GOP Sen. Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin claimed to possess a list of 205 communists working for the government. Less than a fortnight later, he went further and outlined a number of cases, including two who he said were also homosexual.

McCarthy linked communism and homosexuality, characterizing both as threats.

The rationale was that gay people were vulnerable to blackmail since homosexuality was a crime. Because of this vulnerability, they were easy targets for Russia.

"Many assumptions about Communists mirrored common beliefs about homosexuals," National Archives archivist Judith Adkins wrote.

Adkins added: "Both were thought to be morally weak or psychologically disturbed, both were seen as godless, both purportedly undermined the traditional family, both were assumed to recruit, and both were shadowy figures with a secret subculture."

Sources: Variety, History.com, National Archives

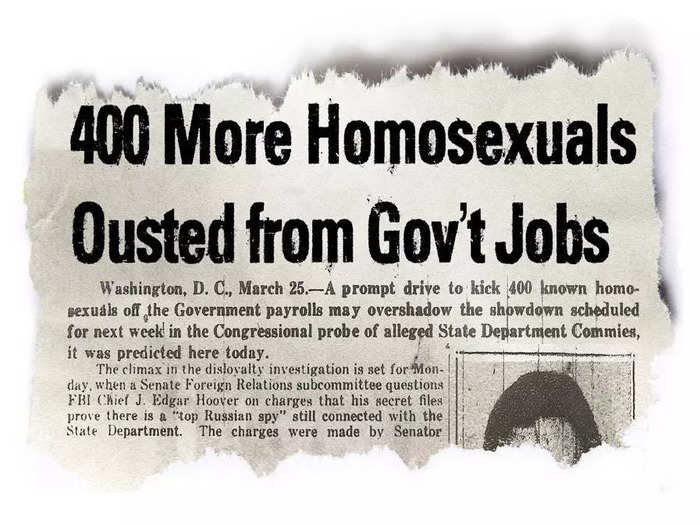

But that didn't matter. When Deputy Undersecretary of State John Peurifoy told the Senate a week later that 91 homosexual employees had already been fired, the damage was done.

The media and politicians were suddenly suspicious not only of communists but of the gay community, too.

The situation wasn't helped by a Senate committee report released in 1950 called "Employment of Homosexuals and Other Sex Perverts in Government."

Among its many comments, the report noted, "One homosexual can pollute a Government office."

Sources: Variety, History.com, National Archives, PBS

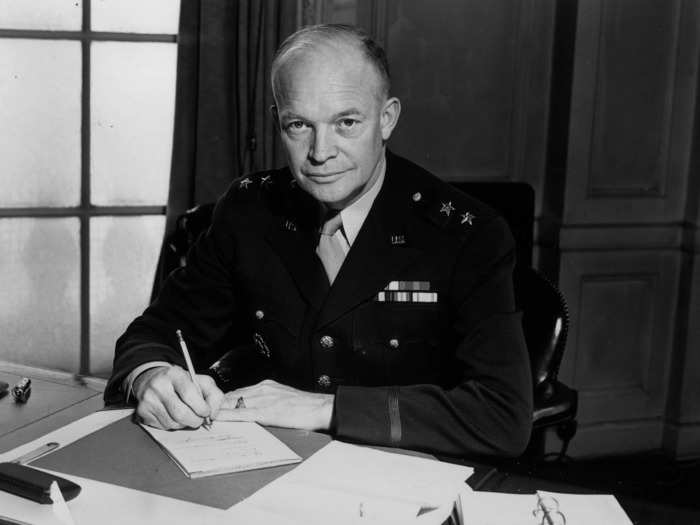

In 1953, then-newly-elected President Dwight D. Eisenhower continued the trend when he described gay people as a threat to the country's security.

He promptly signed executive order 10450, which stated "sexual perversion" was a valid reason for dismissal alongside being an alcoholic or a criminal.

According to the National Archives, "With the stroke of a pen, the President effectively banned gay men and lesbians from all jobs in the U.S. government — the country's largest employer."

Intelligence officers reviewed government employees. They looked for what they considered signs of homosexuality, including the way people dressed or spoke, and whether or not they were married.

Sources: ABC News, NBC News, Variety, National Archives, History.com

Former Navy Lieutenant Joan Cassidy, who was fired because of her sexuality, spoke about her experiences in the documentary "The Lavender Scare."

Employees were called into offices for interrogations.

"They sat behind the big lights and started grilling them, saying, 'We know you're a homosexual because your partner is in the next room,'" she recalled in an interview with ABC News. "She told us, 'You might as well confess.'"

The employees weren't provided with lawyers during interrogation. They were told to name anyone they knew who was gay and worked for the government.

"It was a witch hunt," she said.

About 2,200 women and men were documented as having lost their jobs due to the Lavender Scare. But David K. Johnson, a history professor at the University of South Florida, estimated that the number was as high as 10,000.

Johnson wrote a book on the era titled "The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays."

Johnson said a number of people committed suicide due to the intimidation campaign. One of those people was a man named Andrew Ference, who worked as an administrative assistant at the US embassy in France.

After two days of questioning about his sexuality, he killed himself.

The government later lied to Ference's family about his death, claiming he died from a serious illness.

A key difference between the Lavender Scare and the Red Scare was that in this campaign, no one was named — meaning there were no famous Hollywood directors to tie to the cause.

No one publicly testified as well, whereas the Red Scare had the highly watched McCarthy congressional hearings.

It meant less exposure, which would have made their lives even more difficult, but it also meant they were never seen as real people.

Sources: National Archives, Wall Street Journal

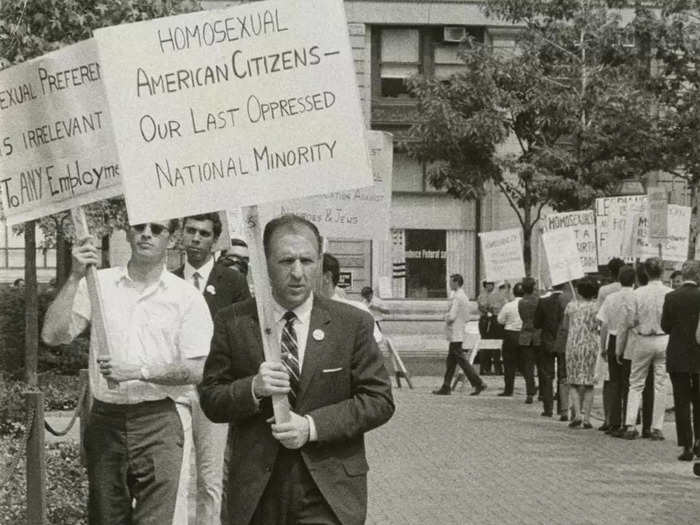

In 1957, astronomer Frank Kameny was fired by the Army Map Service for his sexuality. He'd been job working on a classified missile project. After his dismissal, he became one of the key figures who fought the discrimination.

In one letter he wrote to his mother, he said, "I am right; the world will have to change because I won't."

"If I disagree with someone, I give them a chance to convince me they are right," he told Slate. "And if they fail, then I am right and they are wrong and I will just have to fight them until they change."

Kameny wrote letters to politicians and business people. He formed organizations and took the government to court, appealing his case right up to the Supreme Court, before it was rejected.

He was the first person to petition the Supreme Court on the basis of anti-gay discrimination.

Sources: ABC News, History.com, IndieWire, Wall Street Journal, Slate

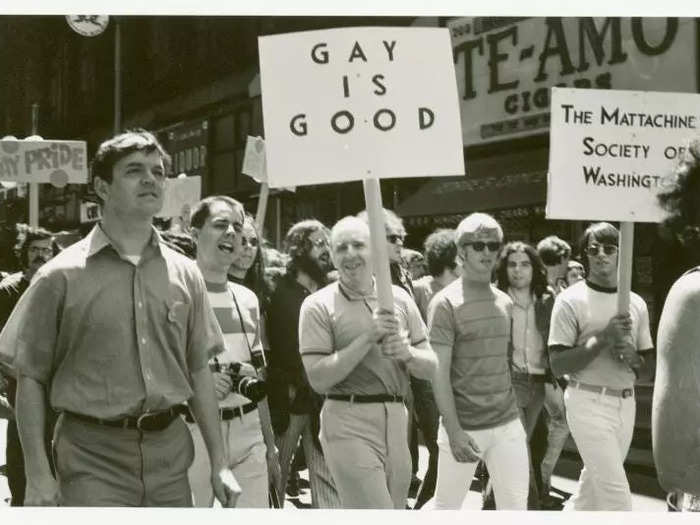

In 1965, Kameny led a protest of 10 people outside the White House. The protest was against systematic discrimination but was triggered by reports that gay people were being forced into labor camps in Cuba.

Source: ABC News, Tampa Bay Times

Despite Kameny's hard work, it wasn't for another decade until the ban against gay people working for the government was lifted in 1975.

Source: National Archives

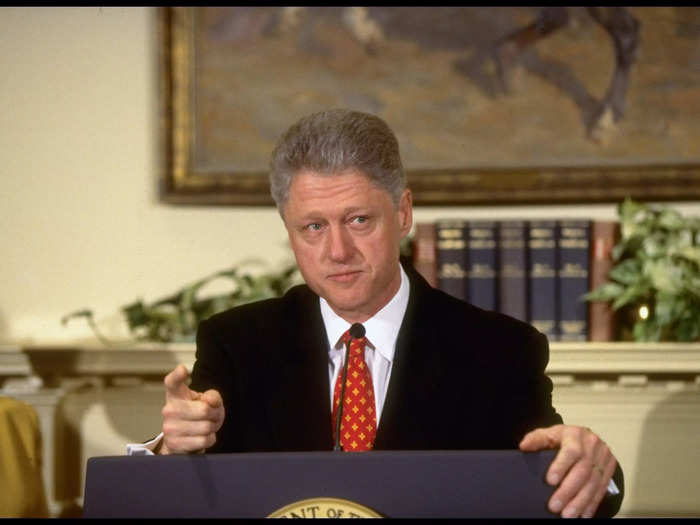

Gay government employees continued to be fired from the State Department until the 1990s due to security concerns. In 1995, President Bill Clinton explicitly ended the order.

Even then, conservative groups backed the law, saying it had been necessary.

Family Research Council analyst Robert Maginnis told the New York Times that homosexuality was a "behavior that is associated with a lot of anti-security markers such as drug and alcohol abuse, promiscuity and violence."

But Kameny was positive about the end of the order. He said it represented "the next step."

"The government has gone beyond simply ceasing to be a hostile and vicious adversary and has now become an ally," he said.

Last year, lawmakers reintroduced the Lavender Offense Victim Exoneration Act, known as the LOVE Act, which aims to "correct historic injustices" by recognizing and reviewing the dismissals of gay employees from the State Department because of their sexual orientation.

Sources: NBC News, ABC News, New York Times, The Hill

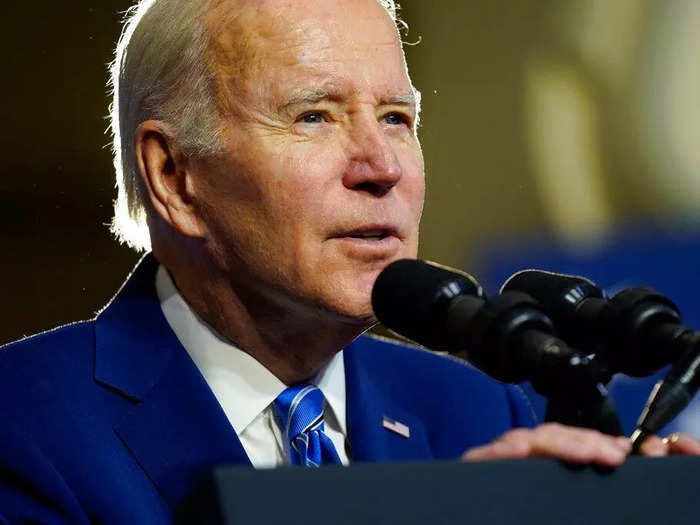

On the 70th anniversary of the Lavender Scare, President Biden issued a presidential proclamation to acknowledge the harmful impact of the campaign.

In the proclamation, Biden declared that the country "has made tremendous progress in advancing the cause of equality for LGBTQI+ Americans," but "must reflect honestly on the darkest chapters of our story."

Source: The White House

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement