Barbara Jordan was one of the first Black and LGBTQ women in Congress, but her relationship was kept secret until her death

Talia Lakritz

- Barbara Jordan was one of the first Black and LGBTQ women in Congress, elected in 1972.

- A gifted orator, she spoke at the Nixon impeachment hearings and two Democratic conventions.

As the first Black woman from a Southern state to serve in the US House of Representatives, Barbara Jordan paved the way for many future leaders.

A member of the Democratic party, Jordan represented Texas in Congress from 1973 to 1979.

She began her political career as a Texas state senator in 1966, becoming the first Black woman to hold the position.

Jordan was born in Houston, Texas, earned a law degree from Boston University, and worked on John F. Kennedy's presidential campaign in 1960.

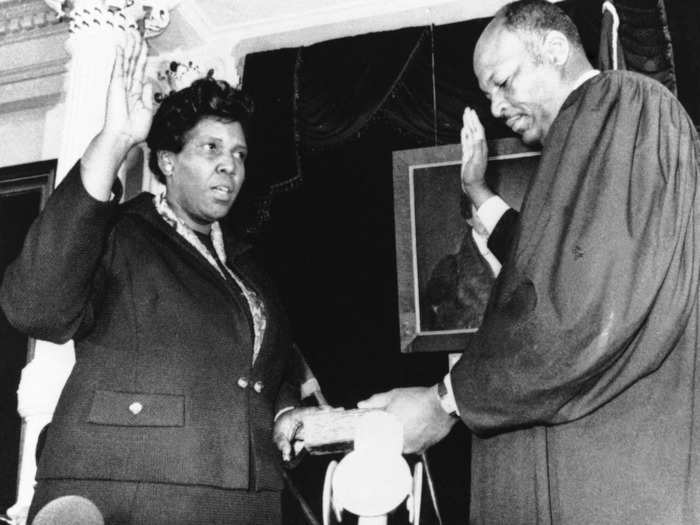

As a state senator, Jordan was elected president pro tempore of the Texas state senate in March 1972, meaning she would act as governor of Texas when the governor and lieutenant governor were out of state. In June that same year, she became the first Black woman to serve as governor of any US state when she was sworn in for the day.

It was during her time as a state senator that she met her longtime partner, Nancy Earl.

In her 1979 autobiography, "Barbara Jordan: A Self-Portrait," she recalled "having a swell time" meeting Earl for the first time on a camping trip with friends in the late 1960s.

"I had had a great time and enjoyed myself very much," she wrote. "I remember I thought: This is something I would like to repeat. I'd like to have another party like that. Nancy Earl is a fun person to be with … I could relax and enjoy myself … I had discovered I could relax at parties like that where I was safe."

Jordan and Earl were together for over 20 years. They bought land in Texas together and built a home in 1976. Earl, an educational psychologist, occasionally helped with speechwriting, and became Jordan's caretaker as her health declined.

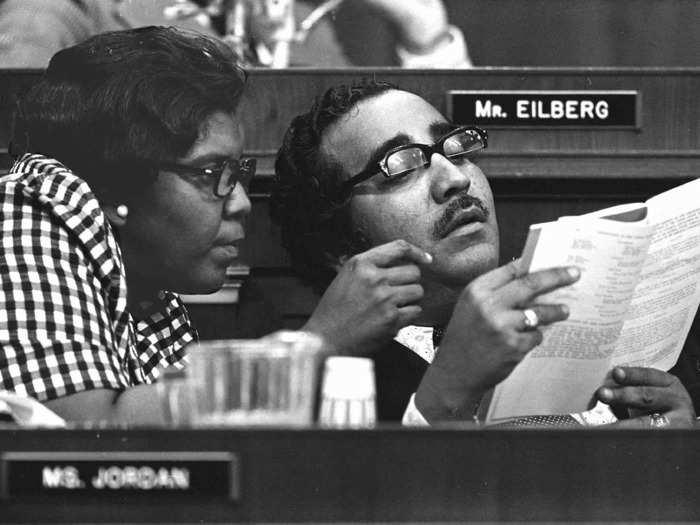

In 1972, Jordan was elected to represent Houston's 18th district in Congress.

Jordan joined other prominent women such as Shirley Chisholm and Bella Abzug in the House of Representatives. Including Jordan, there were a total of 15 women serving in the 93rd Congress, in session between 1973 and 1975.

Today, in the 118th Congress, there are 153.

As a member of Congress, Jordan focused on expanding civil rights protections.

Jordan sponsored a bill adding protections to the Voting Rights Act of 1965 for Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, and Asian American voters that became law in 1975. She also cosponsored Abzug's bill to convene a National Women's Conference in 1977.

Jordan gained national recognition after delivering opening remarks at a 1974 impeachment hearing for President Richard Nixon in the wake of the Watergate scandal.

A gifted speaker, Jordan mesmerized audiences across the country with her primetime televised speech during the Nixon impeachment hearings. She emphasized the importance of checks and balances in the branches of government, and the seriousness of the charges against the president.

"'We, the people.' It is a very eloquent beginning. But when that document was completed on the 17th of September in 1787, I was not included in that 'We, the people.'" she said. "I felt somehow for many years that George Washington and Alexander Hamilton just left me out by mistake. But through the process of amendment, interpretation and court decision, I have finally been included in We, the people.'"

She continued: "My faith in the Constitution is whole, it is complete, it is total, and I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of the Constitution."

Her address is credited with helping move the impeachment process forward, according to The History Channel.

Her star continued to rise as the first Black person and first woman to deliver the Democratic party's keynote address at the 1976 convention.

Jordan spoke about the Democratic party's first convention in 1832, and how far the country had come since then.

"A lot of years passed since 1832," she said. "And during that time, it would have been most unusual for any national political party to ask a Barbara Jordan to deliver a keynote address. But tonight, here I am. And I feel that notwithstanding the past, that my presence here is one additional bit of evidence that the American Dream need not forever be deferred."

She retired in 1979 after three terms in the House of Representatives due to health challenges from multiple sclerosis.

After leaving office, Jordan received the Nelson Mandela Award for Health and Human Rights in 1993, and a Presidential Medal of Freedom, presented by President Bill Clinton in 1994.

She also spent her time teaching at the University of Texas at Austin and chairing the US Commission on Immigration Reform, according to The Houston Chronicle.

While Jordan was open about her sexual orientation with those close to her, she kept her relationship with longtime partner Nancy Earl out of public view.

In a 1996 article in the queer magazine The Advocate, friends of Jordan described her as "straightforward about her sexual orientation in private," Lisa L. Moore, professor and director of LGBTQ Studies Program at The University of Texas at Austin, wrote in the program's online magazine, QT Voices.

"She never denied who she was," a friend of Jordan's told The Advocate, according to Moore. "It just was not the public's need to know.'"

While Jordan broke barriers as a queer Black woman in Congress, she preferred not to label herself.

"I am neither a Black politician nor a woman politician," Jordan once said, according to the archives of the US House of Representatives. "Just a politician, a professional politician."

She delivered the DNC's keynote address once again in 1992, telling fellow Democrats, "We know what needs to be done and how to do it."

In her speech, Jordan blasted the "moral bankruptcy of trickle-down economics" and expressed her hopes for a future Madame President.

"We have been the instrument of change in policies which impact education, human rights, civil rights, economic and social opportunity, and the environment," she said. "These are policies which are embedded in the soul of the Democratic Party. And embedded in our soul, they will not disappear easily. We, as a party, will do nothing to erode our essence."

After she died at age 59 in 1996, she was the first Black woman to be buried in the Texas State Cemetery.

An obituary in The Houston Chronicle described Earl as Jordan's "longtime companion" — the first public confirmation of their relationship.

Jordan's body lay in state in the Great Hall of the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library in Austin, Texas.

In 2011, the United States Postal Service added a stamp commemorating Jordan to its Black Heritage Collection.

"She left Congress after only three terms, a mere six years," Richard Pearson of The New York Times wrote in her 1996 obituary. "No landmark legislation bears her name. Yet few lawmakers in this century left a more profound and positive an impression on the nation than Barbara Jordan."

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement