NASA wants to send humans to Mars in the 2030s - here's the step-by-step timeline

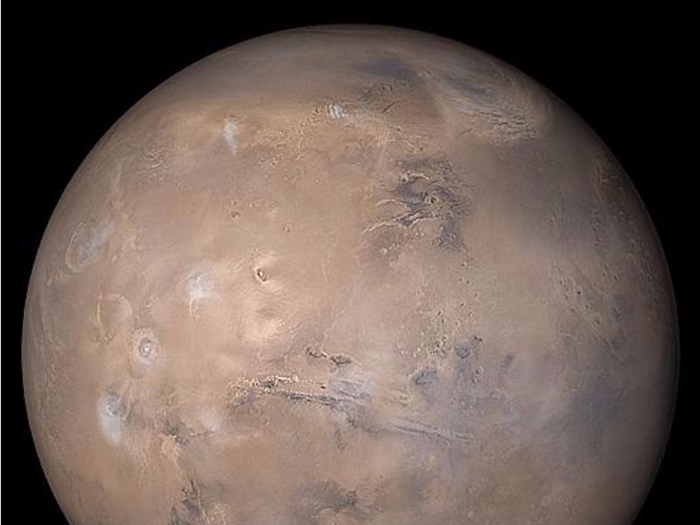

Before attempting to send any people to Mars, NASA needs to learn more about the planet. A new lander is scheduled to arrive on Mars in November 2018.

NASA scientists are calling the InSight mission Mars' "first health checkup in more than 4.5 billion years."

The launch, which was originally scheduled for 2016, has been delayed a couple years, as the agency redesigned some parts. That effort added $153.8 million to the cost of the lander, according to Space News, but it is expected to launch some time between May and June.

Bruce Banerdt, the mission's principal investigator, compared the InSight lander to a doctor that will give Mars a long overdue checkup.

"We'll study its pulse by 'listening' for Mars quakes with a seismometer," Banerdt said in January. "We'll take its temperature with a heat probe. And we'll check its reflexes with a radio experiment."

The mission is now going to cost NASA more than $828 million, Space News reported.

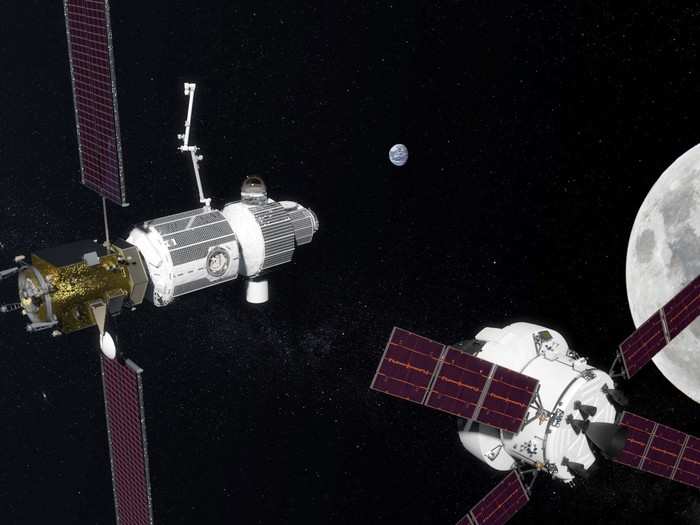

In 2019, NASA wants to spend $10.5 billion to get close to the moon again. That's over half of the space agency's annual budget.

The idea is to build a kind of lunar pit stop that would eventually help humans get to Mars.

The agency's latest plan includes a push for more public-private partnerships on outfits near the moon. That might lead to some swanky new moon accommodations from companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin, or the newly formed Bigelow Space Operations.

US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross recently floated the idea that future missions to Mars might even use the moon as a gas station.

He meant that somewhat literally. Ross floated the idea that astronauts might mine ice from the moon's craters to fuel their future martian missions and cut down on energy use.

But there's no definite timetable for when humans will actually put their toes back down on the moon.

NASA didn't put a hard deadline on getting back to the moon, and things could all change in the 2020 budget, or even as Congress moves forward to approve a final plan for 2019.

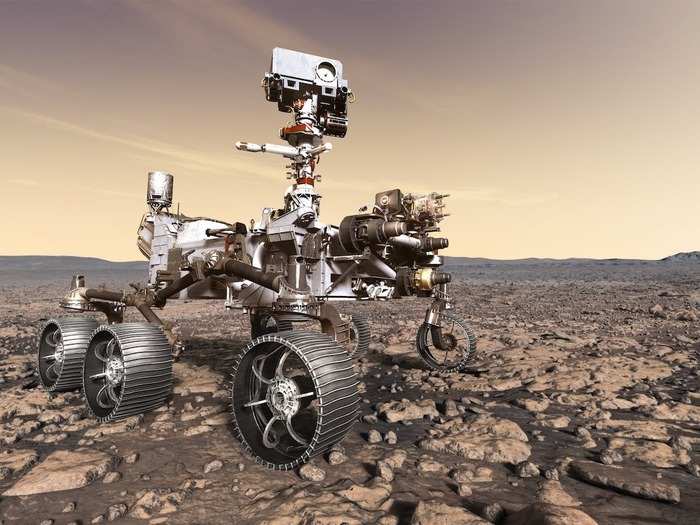

In 2020, NASA intends to follow up its initial Martian 'checkup' with this Mars 2020 rover.

"The Mars 2020 mission is planned to launch in July 2020, landing on Mars in February 2021," NASA said in its full budget proposal.

NASA is aiming to spend $355.4 million in 2019 alone to get its Martian rover ready for action.

Mars is pretty nasty to tires: It ripped some gnarly holes into Curiosity's treads after just a year on the rocky planet. So NASA is developing some new wheels for exploration of the red planet.

They probably won't be ready in time for the 2020 rover, but may be on the rover slated to go in 2024.

The Mars 2020 rover will check for Martians.

Mars 2020 uses a lot of the same hardware as the Mars Curiosity rover, which landed on Mars in 2012.

The main reason NASA wants to send a new rover is to look more closely for tiny Martians. Mars 2020 will use light (a spectrometer) to search for various kinds of organic molecules in Martian soil samples.

NASA aims to devote $50 million in 2019 to developing methods for collecting Martian rocks and soil and bringing them back to Earth for study.

Scientists suspect there may still be elements of life, either extinct or alive today, lying hidden on Mars. Researchers studying the Earth's driest desert recently found some new microbial life there, just waiting for rain. They think it could be a clue that life may silently be humming along somewhere on Mars.

"I fully expect we will encounter life in our solar system," NASA's new Planetary Protection Officer Lisa Pratt said earlier this year.

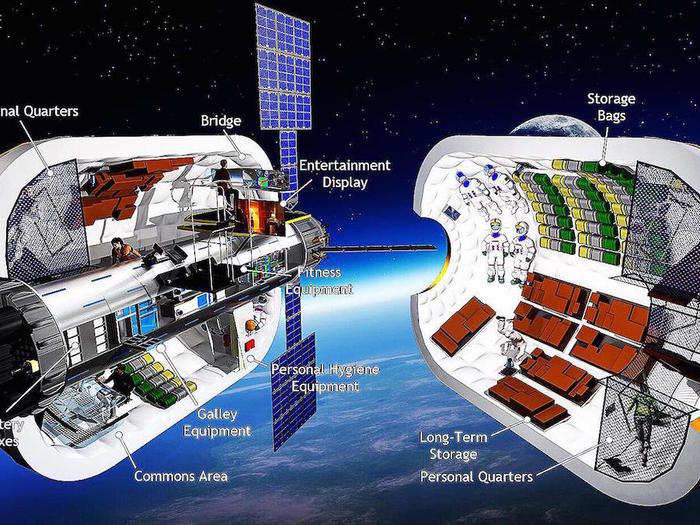

Astronauts are going to need interstellar lodging if they're going to Mars. NASA wants to start developing such accommodations in 2022.

NASA's not ready to send bunk beds into space just yet.

Instead, the agency announced it would like to build a kind of solar-power station, called the "Power and Propulsion Element" (PPE), by 2022. The design and maker of this first-stage power supply will be picked through a competitive bidding process, in which NASA will request proposals from commercial partners.

Eventually, that PPE will power a full-scale "lunar orbital platform gateway": a moon-adjacent version of a space station.

But the new moon station wouldn't be just for astronauts. Because the gateway will be built by a to-be-determined private company, that enterprise could also ferry civilians there. In a way, NASA would kind of be reserving spots in a space dorm built by a commercial entity.

The space dorm could run for more than a decade, NASA says. But first they have to decide who will build it.

Forget the space station. Under the Trump administration, NASA may cut off all funding to the ISS by 2025.

NASA has spent $100 billion dollars over the past two decades on that football-field sized lab orbiting the Earth.

NASA always intended to stop funding the station once it stops being safe to use. But the ISS isn't set to be de-orbited until 2028, so Trump's plan cuts its lifespan short.

The funds that would have been devoted to the ISS would instead help NASA get going on its brand new moon station instead.

Meanwhile, the Chinese have their eyes set on building their own more permanent space station in the 2020s.

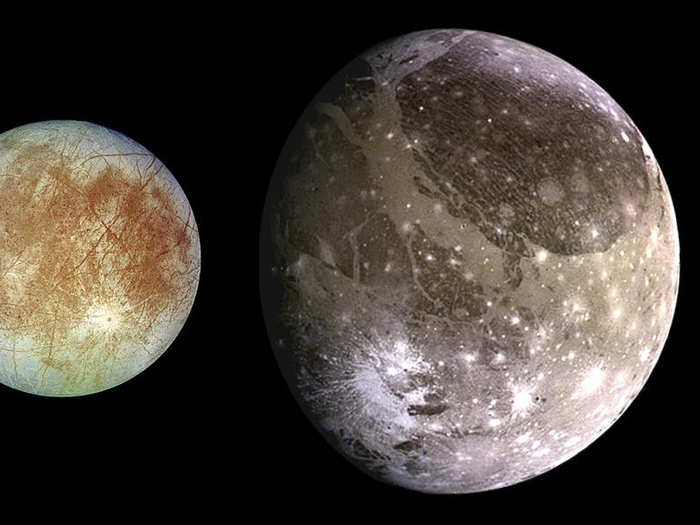

The administration isn't just pushing to go to Earth's moon: In 2025, NASA wants to send alien scouts out to Jupiter's moons.

The agency is planning to launch a "clipper" toward Jupiter's icy moon Europa in 2025 to investigate if that's a place where life could survive.

NASA is earmarking $50 million for the Europa Clipper mission in 2019 alone.

But can NASA really get to Mars by the 2030s?

It's important to note that a lot of these plans won't happen until President Trump leaves office, even if he were to serve a second term through 2024.

Like other areas of the federal government, NASA's work depends on each administration's priorities for how to spend money in space. That can make it tough to predict which of NASA's projects ultimately get funded or finished (and lead to spending waste, since NASA's missions often last much longer than a single presidential administration).

It's clear for now that the Trump team seems gung-ho about getting to the moon.

But they're not making the task easy — the federal government's notional proposed budgets for NASA from 2020-2023 slash the space agency's annual funds down to $19.59 billion. That number doesn't take inflation into account, and is even less money than the $19.65 billion that was earmarked in NASA's 2017 operating plan.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement