- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- 'Why should we make foreigners rich?': Taxi drivers are taking on Uber and Grab in Bali, and some are turning to violence

'Why should we make foreigners rich?': Taxi drivers are taking on Uber and Grab in Bali, and some are turning to violence

Nearly 5.7 million tourists visited Bali last year. Like everywhere else, ride-sharing apps have become the popular way to get around.

Even before arriving I was warned off using ride-sharing apps lest I incur the "taxi mafia's" wrath.

As I rode to my hotel in Ubud, a city in central Bali known for its proliferation of spiritual healers, yoga retreats, and vegan cafes, I spotted signs with red x's over the logos of the most popular ride-sharing services and a plea to "Support the local economy."

In the eyes of Bali's taxi drivers, ride-sharing companies profit off their communities and give nothing back.

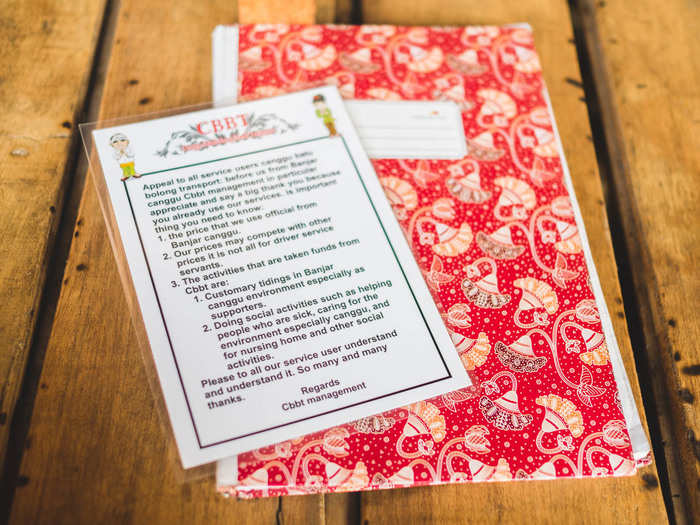

At the taxi stand in Caangu, I met Wayan Tono, the stout 50-year-old head of the Caangu Batu Balong Beach Transport, a taxi cooperative made of 165 drivers from the banjar of Batu Balong.

Tono, a proud man with a white button-down opened halfway to his puffed chest, explained that ride-sharing apps disrupts the system that has dictated Balinese culture for hundreds of years.

Each village in Bali is subdivided into multiple banjar, or sub-villages, that are often not bigger than a square mile and maximum of 500 people.

Each banjar acts like a co-operative where the residents determine nearly every aspect of daily life at mandatory community meetings — everything from building local roads and land use to punishment of local crimes and administering religious ceremonies. The drivers in Tono's co-op were all natives of the Batu Balong banjar.

When Tono said that they were locals — which he and his fellow drivers said repeatedly — they didn't mean Balinese. They meant the literal ground we were standing on.

Ever since ride-sharing apps launched in Bali in 2015, there has been tension. Taxi drivers view ride-sharing drivers as worse than the companies, because they know Bali's unwritten laws.

The tension between ride-sharing apps, their drivers, and taxi drivers has been present since the apps launched in Bali in 2015.

In the months after the launch, taxi drivers erected signs marking their banjars as no-go zones and then began to aggressively enforce those territorial lines. Taxi drivers protested repeatedly in Denpasar, the capital, to call for the governor to ban the services, which they argued were unfairly charging fares so low they couldn't compete.

In Tono's eyes, Uber and Grab profit off their community and give nothing back. His drivers, he said, had built the road we were standing on when the provincial government wouldn't. Ride-sharing drivers are even worse because they should know better, at least the Balinese. Many of the drivers hail from other Indonesian islands like Surabaya or Java.

"It's simple. This is my village. I work here. I respect this place," Tono said. "We all work together. That's money we share and use together."

In Bali, taxi drivers' prices are twice that of Grab and Go-Jek. But, they argue, they can't lower the prices because 30% or more of their fares go back to the communities.

While rules vary from banjar to banjar, nearly everyone follows one tenet that has exacerbated the pricing issue at the heart of every clash between taxi and ride-sharing drivers across the world: Due to the extreme territorialism, drivers are only allowed to pick up passengers in their own banjars, which means that for a one-way fare, they must drive and pay gasoline for a round trip.

Further, each banjar has its own taxation structure.

The Batu Balong banjar, to which Tono and his drivers belong, dictate that drivers net only 70% of each fare, with the rest going back to the community: 10% for road maintenance, 10% for religious ceremonies, and 10% for the pecalang, or Balinese traditional police who handle issues the official police won’t deal with — basically everything except serious crimes. Another 10% goes to the taxi co-op that all the drivers belong to, money which is used for lawyers, car insurance, and loans for drivers in need. If there is a profit, drivers are paid out at the end of the year.

No wonder a ride through Grab or Uber is a tenth of the price.

The taxi drivers were unwilling to give up in the face of technology's pull. "Bali is not an application. In Bali, we have traditions," one driver told me.

As Tono and I talked, another driver, with a long face and wary eyes, interrupted in rapid-fire English, as though he'd been waiting a long time to be heard by those who usually ignore him — i.e. tourists like me.

"Bali is not an application. In Bali, we have traditions. Maybe in Java, they don't have traditions. But in Bali, we have traditions. Maybe another country doesn't care. We care," he said, declining to give his name.

When I told him that I had taken a Grab the night before, the driver was infuriated, asking me how I'd like it if someone from the internet decided to do my job for a fraction of the price. When I explained that had happened across journalism, and tons of other industries, it didn't register.

Indeed, despite three years of disputes, the issue is far from solved.

In 2016, violent protests broke out in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia. Taxi drivers clashed with ride-sharing drivers. In the years since, there have been frequent confrontations, harassment, and threats from taxi drivers.

Drivers have protested since the beginning, but both the Indonesian and provincial Balinese governments intervened in 2016 after violent protests in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia.

The Bali Transportation Agency ordered a temporary ban on ride-sharing services in April of that year, while Indonesian Transportation Ministry declared ride-sharing apps illegal around the same time. In order to continue operating, Uber and Grab and its drivers would have to act like a traditional taxi company — obtain licenses, pass required driving tests, and use a taximeter similar to the government-regulated fare.

The government rulings did little to stop ride-sharing companies and their drivers or to relieve the tension.

The most brutal incident in Bali came last year when an Uber driver was beaten and his car smashed for trying to pick up a passenger in south Bali.

The brutal beating of an Uber driver in 2017, which reportedly occurred while he'd been trying to pick up a passenger at a hotel in Seminyak, a popular beach resort area in southern Bali, blazed across the headlines. The drivers allegedly demanded he pay them a 500,000 rupiah ($35) "fine." When he refused, the drivers dragged him from his car, beat him, and then smashed his car with rocks and wooden beams.

Many more incidents have gone unreported or get settled with local police, according to taxi drivers and ride-sharing drivers I spoke to.

No amount of violence or anger has, as of yet, dissuaded Indonesians from working for Uber, Grab, or Go-Jek. The demand from western, and even Indonesian, tourists is too great.

There are few things more comforting when traveling than being able to open the app you use at home and finding that it works the same.

And, ride-sharing drivers argue, the money is better: An Uber driver named Budi told Southeast Asia Globe that, in a good month, he could earn $1,800. Taxi drivers I spoke said they make $212-$354 in the busiest months. Minimum wage is around $125 a month.

For a while, I felt my perception of taxi drivers as a price-gouging "taxi mafia" was correct. But Gede Hendra, the head of a taxi co-op, encouraged me to see the situation from their point of view: Why should tourists pay the same as their impoverished countrymen?

As I rode home in the Grab that night from Old Man's, I was self-righteous about my interaction with the taxi driver. Everything I'd heard about the taxi drivers was true, I thought. They were just looking to price-gouge tourists; the price I'd been quoted was more than double what my Balinese host told me he was usually charged.

Gede Hendra, the vice-president of Caangu Beach Transport, a larger umbrella cooperative formed in 2009 under which Tono's stand operates, encouraged me to view the price-differential from their perspective: Why would it make sense that locals pay the same as tourists visiting from places like the US, Europe, or Australia, who often earn ten times what locals do? Further, didn't it make sense that the Balinese, who open their communities to tourists and who create much of the infrastructure that spurs development, should get the jobs from those tourists?

"We don't want to be bystanders with the tourism industry. We want to get involved and make a living. We care about the development of this area. The online taxi drivers don't care about anything. They just come, take the passengers, and go," Hendra said.

"We want to serve the tourists and protect Bali."

Hendra said he and his fellow drivers want to protect their community from turning into nearby Kuta, a resort town overtaken by tourism where few locals benefit.

To that end, Hendra emphasized repeatedly that he and his ilk cared little if locals used ride-sharing services (I should note this was not true for drivers at other, poorer taxi stands I spoke to). Public transportation is nonexistent in Bali. Most locals have their own scooter or motorbike to get around, but if they need a cheap ride to the hospital, Hendra said, he wasn't going to stop them from using Grab.

Hendra went on to explain that the taxi-ride-sharing issue is really about keeping a Balinese stake in the development of their communities.

He pointed to Kuta, the island's most popular beach town and one frequently called Australia's 'Cancun' due to its reputation as a haven hard-partying college-age Australians, over-developed resorts, and trash-filled beaches. As tourism has increased and savvy travelers have sought to avoid what one travel blogger called “the worst place in Bali,”

Caangu has sprouted up over the last five years as the hip Brooklyn to Kuta's Manhattan. The beaches are relatively clean and the town has developed a chic main street of French bakeries, brunch spots, tattoo parlors, and swanky beach bars. Hendra is happy about the influx of tourists, but he doesn't want to see his banjar turn into Kuta, where nearly all of the revenue goes to foreigners.

Hendra worries that the low price of ride-sharing companies will drag down the prices of other tourism services, from guides to restaurants and hotels.

"How can you provide good service if the price is very low?" he asked.

Indonesia set forth stricter rules on ride-sharing companies earlier this year. But Bali's taxi drivers believe they don't go far enough.

At the end of the day, of course, it all comes back to money, and much the same issues that ride-sharing companies have encountered in every market they've entered. The Balinese taxi drivers see their market flooded with competition, shockingly low prices, and another middle man they have to pay to get work.

Indonesia set forth a stricter regulatory regime last year that was set to go into effect in January, one stipulation of which was that ride-sharing companies would have to register as transportation companies so that the Indonesian transportation ministry would have jurisdiction over them.

As part of the new regulations, ride-sharing taxis were legal but drivers would have to register their cars as tourist vehicles and could only operate in certain areas. As of March, 1,426 drivers have registered with Bali's Department of Transportation.

Around the same time, Uber sold its Southeast Asia business to Grab for a 27.5% stake in the $6 billion company. It seems likely that the tightening regulatory environment played a role.

Bali's taxi drivers have argued the regulations don't go far enough: They want the services either banned or forced to raise their prices so they can compete. Drivers have assembled repeatedly in Denpasar to demonstrate in front of the governor's office.

"They know that Grab and Uber are owned by foreigners," Bali Drivers Alliance chairman Ketut Wirta said at a demonstration in January. "Why should we make foreigners richer?"

Bali's taxi drivers are putting their hopes in Wayan Koster, one of the island's two candidates for governor, who has promised to address the ride-sharing issue.

The day before I met with the drivers, most had been to a demonstration. But that demonstration had been unique — the drivers were meeting with Wayan Koster, a member of Indonesia's House of Representatives and one of Bali's two candidates for governor. Koster has made addressing ride-sharing a key part of his platform.

According to Hendra, Koster promised to push regulations that would force ride-sharing companies to raise their prices significantly and prevent them from operating in certain areas. Ride-sharing services are already prohibited from operating at the airport.

Whether Koster would make good on those promises if he wins — the election is June 27 — is anybody's guess.

As Parkestit, my translator, told me, Balinese politicians are known for making big, empty promises.

Taxi drivers told me that the violence has tailed off. Ride-sharing drivers understand where they can work and where they can't, they said.

All of which explains the conflict, but not the violence. Balinese have a reputation as a peaceful people. But as Hendra explained, when it comes down to your ability to put food on the table for your family, things get ugly.

"Imagine that you live here and maybe you go a long time without work. Then you get hungry. Then someone comes into your village and takes your client," he said. "Wouldn't that make you angry?"

Hendra argued that the "taxi mafia" image is one propagated by ride-sharing drivers, much to their own benefit. At this point, he said, ride-sharing drivers know which areas they are allowed to pick up passengers and which areas they aren't.

In the rare case that a new driver comes into their banjar, they stop him and explain the situation. Most of the time, the drivers leave. Occasionally, it turns into a verbal argument.

I was willing to take Hendra, whose taxi stand seemed to be one of the busiest, at his word, but I was skeptical that there weren't others that acted more aggressively.

But tourists, travel bloggers, and ride-sharing drivers continue to talk about scary run-ins with taxi drivers. It's hard to believe that, as more people and drivers use the apps, they've let up.

Many tourists and travel bloggers have written about their experiences with the so-called "taxi mafia."

Kate Alvarez, a Philippines-based lifestyle journalist, described in a February blog post how a group of taxi drivers followed her around Ubud as she waited for an Uber to pick her up. Eventually, she hid in a cafe, cancelled the ride, and called a private driver whose number she had. When that driver showed up, the taxi drivers interrogated him.

Budi, the Uber driver, told Southeast Asia Globe in May that he has been threatened and chased by taxi drivers repeatedly. In one particularly harrowing incident, Budi recounted how a taxi driver tried to pry open his car door when he picked up a passenger. When he refused, the man and three of his friends carved a "U" on the back of the car.

These days, he starts working at 4 a.m., as he is less likely to have run-ins with other drivers.

And as Parikesit explained, in many parts of Bali, it’s not just the banjar getting squeezed. In Bali, it is not uncommon for popular areas like shopping malls, beaches, or tourist attractions to be controlled by local thugs.

If a taxi driver wants to operate in the area, he or she has to pay a fee of sometimes thousands of dollars to the men, who give the drivers a kind of ID that allows them to operate there.

Further, many areas are controlled by keluarga besar — large gangs that control "security" for certain villages and have their hands in a variety of legal and illegal activities. One can imagine that when ride-sharing drivers trespass those groups, retaliation is brutal.

Some drivers, like Nyoman Trirata, are tired of fighting tourists and ride-sharing drivers. He just wants to get back to working.

For the taxi drivers, fighting ride-sharing companies has been like fighting the ocean.

Nyoman Trirata, a sun-weathered 49-year-old whose voice cracks with hardships, is tired of fighting. Trirata runs a taxi stand half a mile from Tanah Lot, a seaside Hindu temple popular among tourists for its sunset views. His stand used to be inside a hotel, providing plenty of work, but it closed a few months ago and they've had to move down the road.

Most day trippers to Tanah Lot come with their own car or private driver. He and his drivers sometimes go days without a fare.

"It's more effective for me to get a job than to go to a protest. The government doesn't care about what we say," he said.

Trirata has lowered his prices to compete with Grab and some of his drivers have signed up for the app. They won't take Grab fares in their banjar, but if a fare takes them across the island, they'll try to get fares on the drive back. Both are major taboos at the other stands.

The more I talked to drivers on both sides, the more it became clear that the ethical choice was to support the taxi stands. But, it's difficult when they are both more expensive and less convenient. It seemed likely that it's only a matter of time before they are wiped out.

In some sense, I too felt the drivers were fighting an unstoppable force. On my last day, I contemplated getting a taxi to the airport, but the prospect of dragging my luggage a few blocks to the taxi stand to pay two or three times the fare wasn't appealing. I felt bad — then I ordered a Grab.

My driver was a 20-year-old university student studying hospitality named Made. His father had been a taxi driver for decades in Bali, but had taken up with Grab as soon as it launched. His father had encouraged him to drive when he wasn't studying so he could earn some money and practice his English with tourists.

Made's father was invested as anyone in Bali's banjar system — he had established the taxi co-op in Jimbaran, a fishing village south of Kuta. But his father sold his car in 2014 because he was tired of the headaches and payoffs that came with the system. When Grab arrived in 2015, his father bought a new car and started driving again. In his father's eyes, Made said, ride-sharing apps leveled the playing field.

When Made was old enough, his father showed him the unspoken banjar territorial lines that dictate where he could and couldn't pick up passengers. Most ride-sharing drivers, he said, respect the banjar lines, but arguments still happen from time to time.

Besides, he said, the half of taxi drivers whose cars were new enough to be eligible for ride-sharing — apps usually won't allow cars older than 5 or 10 years — now work for the apps. The rest, he said, are just angry that they aren't eligible.

At the time, Made's explanation assuaged my guilt over using Grab. But now, looking back, it seems that when it comes to the question of which locals benefit, it's the ones that have more money — enough for a newer car — that are getting paid. Those from the poorer banjars — 35% of Balinese live below the poverty line — are the ones getting screwed.

Given Westerners' expectation of technological convenience, it's unlikely that will change anytime soon.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement