- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- Tens of thousands of Chinese live at the mercy of Apple's factories - and they don't even work there

Tens of thousands of Chinese live at the mercy of Apple's factories - and they don't even work there

Liu was 18 years old when she and her husband decided to leave their hometown to work at Foxconn's then-flagship factory complex in Shenzhen.

Apple and Foxconn's fortunes and prosperity have become increasingly intertwined since 2005, when Liu started working at Foxconn's Shenzhen factory.

In 2005, Foxconn was growing into its status as the world’s largest contract electronics manufacturer. The company had contracts with major electronics companies like Dell, Sony, and, most importantly, Apple.

At the time, Apple’s best selling product was the iPod.

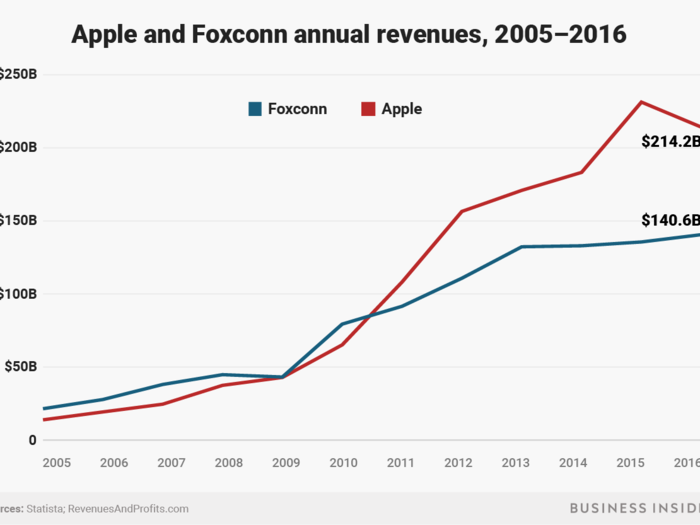

The couple worked at the Longhua factory for five years. Over that time, Foxconn and Apple’s relationship deepened and so too did the companies’ fortunes become intertwined. In 2005, Foxconn’s revenue totaled $21.54 billion. In 2007, the year Apple introduced the iPhone, the company’s revenue jumped to $38.11 billion. In 2010, it nearly doubled to $79.38 billion.

Foxconn’s reliance on Apple has increased with revenue growth. In 2009, Apple products accounted for around 25% of Foxconn’s revenue. By 2012, it was up to 60%. It has hovered between 50-60% in the years since and, while revenue grew to $110.79 billion in 2012, it has hovered between $130-$140 billion in the years since.

Today, Foxconn is by far the country's largest private employer, with 1.3 million employees in mainland China. Apple claims it supports 4.8 million jobs in China.

Foxconn has faced accusations of labor abuses, poor working conditions, and harsh penalties for workers who make mistakes throughout its recent history. Investigations of working conditions at Foxconn during Liu’s time (2005-2010) found workers to be both underpaid and overworked.

The Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) reported in 2005 that the average worker works 27 days per month for 10-11 hours per day and earns 1000 RMB ($157) per month, including overtime. In 2008, SOMO found that workers had to work compulsory overtime leading to 70-hour work weeks on average.

There was a wave of suicides among Foxconn workers in 2010 and 2011, prompting Apple and Foxconn to make changes at the factories.

When Foxconn opened its massive factory complex in Zhengzhou, it started a massive migration of Henanese returning to their home province. Liu was one of them.

When most people think about the economic impact of a large company, it usually stops at the jobs at the factory or the office park and the tax revenue. But Foxconn’s immense labor needs have the ability to shift an entire population to a new place.

As Liu Miao, the head of a private recruiting center in Zhengzhou, told The Times in 2016 of Foxconn's labor needs, "Every city's department of labor and ministry of human resources is involved" in sourcing workers from the province.

In the case of the Foxconn Zhengzhou Science Park, it had the effect of bringing home a migratory workforce.

In 2010, Liu and her husband decided to leave the Longhua factory when they heard that Foxconn was setting up a factory complex, even bigger than the one they worked at, on the outskirts of Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan.

They packed up their life and headed home. As happens whenever Foxconn or another manufacturer opens up a factory in China, hundreds of thousands migrated for the work. Many, like Liu and her husband, were Henanese returning home.

One night in iPhone City, we had dinner with a table of Foxconn workers eating and drinking beer at an outdoor restaurant. All four — whose ages ranged from 22 to 40 — were Henanese who returned to the province after working in factories in other parts of the country.

They emphasized that, in a workforce ranging from 120,000 to 350,000, there is bound to be diversity, but most of their coworkers were Henanese who moved to Zhengzhou to be closer to home.

"People like to work at this factory because you are close to your family if you are from Henan," Liu said. "You get Sundays off and you can go home and visit your family. That’s the perk."

Many people who work at factories farther from their hometown see their families only twice a year, on Chinese New Year's and National Day.

Like thousands of those that migrated, Liu had no intention of working at the factory. She had an idea for a better life, though years later, it still eludes her.

What makes Liu unique is that, though she was migrating home, and she had no intentions of working at the factory.

Liu and her husband decided to use their savings to open up a restaurant for hungry factory workers who would inevitably be looking for better food than Foxconn’s cafeteria could offer. Liu knew that the food at the factory would be bad; she’d spent years eating at the one in Longhua.

“The noodles are barely cooked,” she said with a laugh.

Liu and her husband saw the new factory as a way out of the factory lifestyle while living closer to her lao jia — about a one-hour drive from Zhengzhou — where her son was being raised by her parents.

Liu has found that, for her family, there is no way out of the grinding poverty that has marked her life both as a factory worker and a restaurant owner.

A better life has receded before their eyes.

For all of the legitimate criticism of Foxconn's labor practices, Foxconn workers we spoke to said time and again that the factory was neither better nor worse than the dozens of other factories in China where they had worked.

Liu was unequivocal that the lives of the vendors and restaurant owners — most of whom are ex-factory workers — are harder than those at the factory.

Vendors open their restaurants early in the morning to cook breakfast for the day-shift workers and stay open through lunch. After lunch, they clean up and sleep for a few hours. They reopen around 7 p.m. for dinner and the night-shift workers and stay open until the night workers' lunch at 1 a.m., then go to sleep around 3 a.m., after cleaning the restaurant. Most nights, Liu and her husband sleep only three or four hours.

Liu understands the appeal of working at Foxconn, where, she says, the pay is higher. Foxconn has raised its wages to 1,900 yuan ($300) a month, and workers can raise their monthly salaries to about $676 depending on how much overtime they work or how long they stay at the company.

There's less pressure, too, Liu said. Factory work may be boring and repetitive, she said. But you don't have to worry.

"There's more pressure running your own business," she said. "I have to think about what I'm missing. I have to worry if business isn't good."

Liu's livelihood, like that of all iPhone City residents, is subject to the choices of Foxconn and the local government. Entire livelihoods could disappear without warning.

Liu worries a lot about business.

This year, the factory seems quieter than usual, she said. Half of the businesses in the makeshift village are closed, as the district where she and 20-30 other vendors and restaurants serve workers is scheduled to be demolished by the end of the year.

No one is positive what will replace the village, but Liu has heard rumors that the government wants to turn the scrublands around the factory into gardens. A new airport is situated next to the factory. No one wants to look at a shantytown and dirt when they fly in, she said.

The threat of demolition has scared most vendors and restaurant owners out of the makeshift restaurant district. Many were afraid they would pay their landlord rent for the year and be unable to get it back when the trucks arrive, Liu said.

But even with less competition, Liu and her husband are making a fraction of what they did in 2014, 2015, and 2016. Liu estimated that at the time of the year we visited, early May, the factory usually has 120,000 employees. This year, she said, it seems like half of that.

Liu's anecdotal evidence is hardly fact, but perhaps reports that iPhones sales are experiencing a sharp decline point to the idea that less iPhones need to be manufactured this year.

By way of evidence, Liu motioned to trays of premade food behind a deli counter. Two years ago, she said, all that food would be sold in the half-hour after opening in the morning, even during the slow months.

We were there around 2 p.m., after lunch, and the trays were still more than half full. Liu used to be so busy that she had to have six full-time employees. Now she is down to two.

If Foxconn or Apple's fortunes turn — or the promise of automated iPhone factories comes to fruition, as looks to increasingly be the case — it won't be just the factory workers who lose their livelihood.

As Liu told me about the impending demolition and the way her business swayed with the rhythms of the factory, we were reminded of a passage from a recent piece by New Yorker's Jiayang Fang about centralized efforts to transform the economy of a poverty-stricken coal region in northwestern China into a world-renowned wine industry.

While visiting a vineyard, Fang speaks to a farmworker who, when asked how her life was, repeated a peasant phrase common to the region, "kao tian chi fan — to rely on the sky for food." When one is farming, life is made good or bad by the rain; you have little control over it.

By the end of the piece, Fang likens this attitude to China's modern era, but the government has become the sky:

"The government's schemes, centrally planned and then implemented in province after province, can make fortunes, ruin lives, or leave social hierarchies much the same as they were before … The sky could ripen your vines or ruin your crops and there was nothing you could do about it. Here the government was no different: a distant power inscrutable to those on the ground."

Liu seemed to view Foxconn and the local government in this way as well. When I asked what she would do when the bulldozers came, she smiled as though we had asked about the weather.

"I guess we'll move somewhere else, set up our restaurant, and do the same thing," Liu said.

Other business owners in iPhone City had a similar "what can we do" shrug to Foxconn. Ma, a 25-year-old masseuse from Zhengzhou and a former factory worker, told Business Insider that all of the businesses nearby were losing money at the time. Everyone was just trying to hold on until the usual swell of workers in June.

"They can't afford the rent right now," she said.

The ones that can't hold out will close up shop, and some other hopeful will try their hand at the game.

And, if the fortunes of Foxconn or Apple turn — or the companies turn to automation, as looks to be increasingly the case — all that will be left to do is look to the sky.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement