- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- Sugarcoat, mulligan, and 9 more words we can credit to US presidents

Sugarcoat, mulligan, and 9 more words we can credit to US presidents

Iffy — Franklin D. Roosevelt

Mulligan — Dwight Eisenhower

Before Dwight Eisenhower came around, the word "mulligan" was rarely heard outside the golf course.

But according to Dickson, Eisenhower — an avid golfer — introduced the word to the masses in 1947 when he requested a mulligan in a round of golf that was being covered by reporters.

A mulligan is an extra stroke awarded after a bad shot, and it wouldn't be the last time Eisenhower was awarded one. In 1963, the former president was granted a mulligan as he was dedicating a golf course at the Air Force Academy, after his ceremonial first drive went straight up into the air.

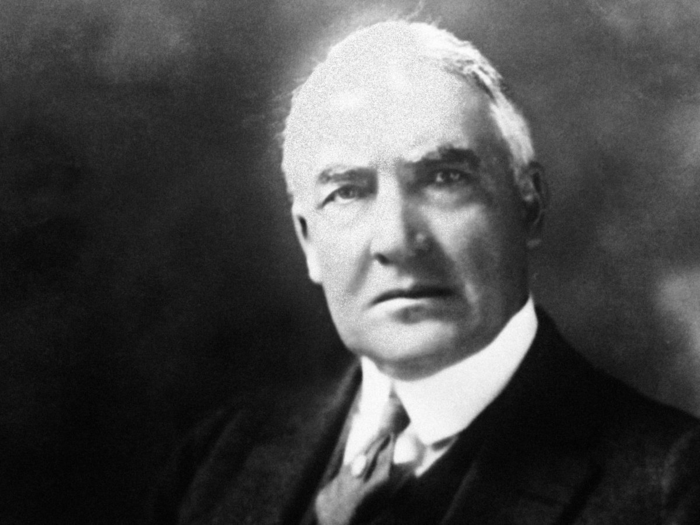

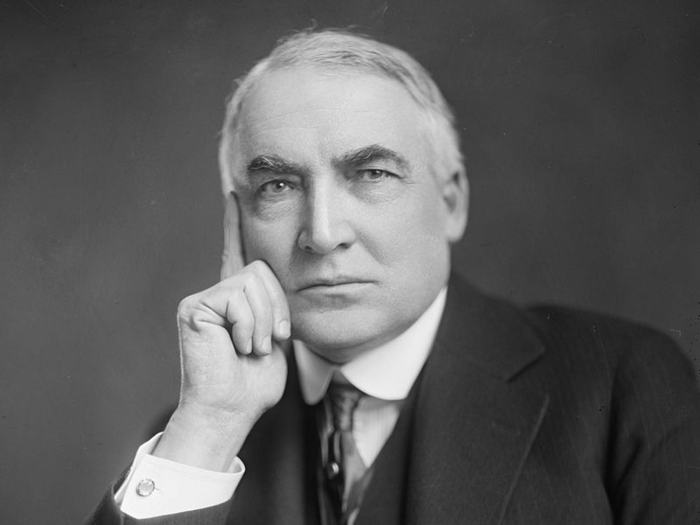

Founding fathers — Warren G. Harding

Warren G. Harding is usually ranked among the worst American presidents, but he succeeded in popularizing a phrase that has become a staple of our political discourse.

The most famous instance came in 1918 when Harding, then an Ohio senator, said in a speech that "It is good to meet and drink at the fountains of wisdom inherited from the founding fathers of the Republic."

Before Harding, America's pioneers were typically known as the "framers." But Harding's punchy alliteration soon became the standard for decades to come.

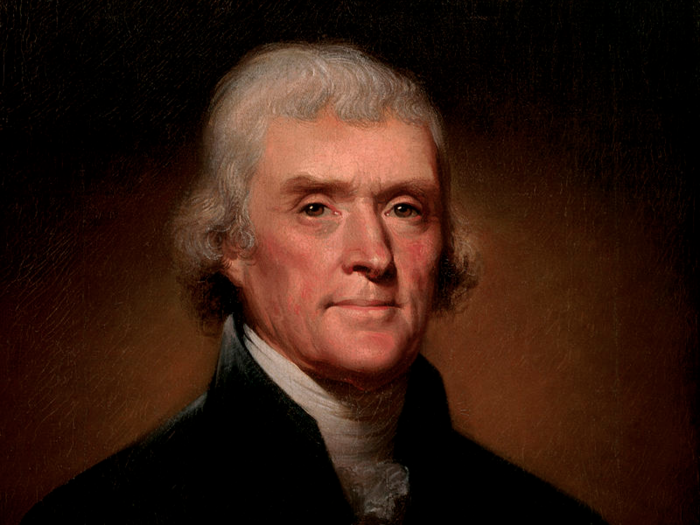

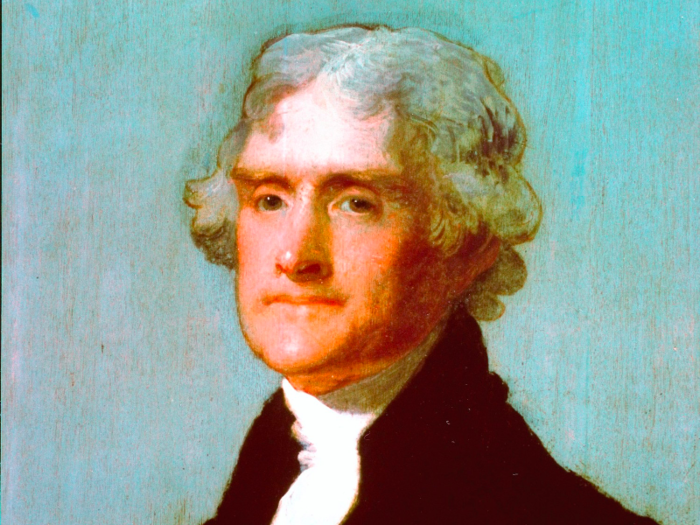

Pedicure — Thomas Jefferson

Perhaps no president has contributed more words to the English language than Thomas Jefferson.

One of his most widely-used contributions is the word "pedicure," which he picked up during his years living in Paris. The earliest use of the word in English dates back to 1784, according to Merriam-Webster.

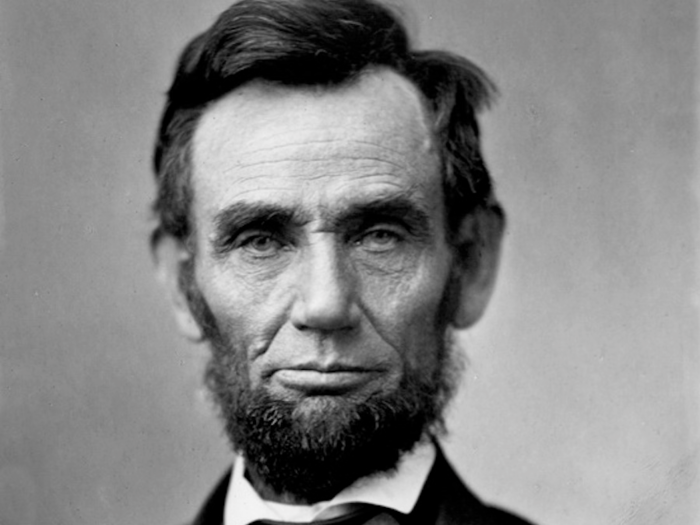

Sugarcoat — Abraham Lincoln

Not only did Abraham Lincoln pioneer the use of "sugarcoat" in the sense of making something bad seem more attractive or pleasant, but he stirred up a minor controversy with the word, too.

In 1861, four months after he was inaugurated, Lincoln wrote a letter to Congress as Southern states were threatening to secede from the Union.

"With rebellion thus sugar-coated they have been drugging the public mind of their section for more than 30 years, until at length they have brought many good men to a willingness to take up arms against the government," Lincoln wrote, according to Dickson.

John Defrees, in charge of government printing, was so incensed by Lincoln's folksy verbiage that he admonished the president, telling him, "you have used an undignified expression in the message."

But Lincoln insisted on using the word "sugarcoat," and he got the last laugh: "That word expresses precisely my idea, and I am not going to change it," he responded. "The time will never come in this country when the people won't know exactly what 'sugar-coated' means."

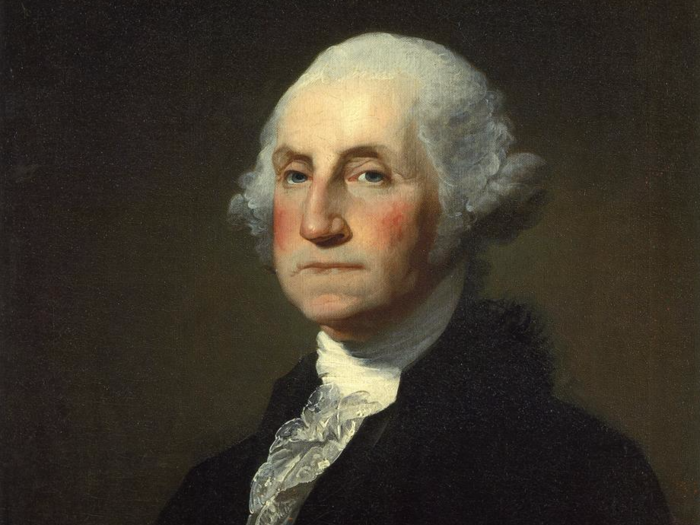

Administration — George Washington

George Washington set the standard for all US presidents to come, and one major impact he had was establishing the language of the presidency.

Although the word "administration" has been around since the 14th century, it was Washington who first used the word to refer to a leader's time in office. According to History.com, Washington's first use of the word came in his 1796 farewell address when he said, "In reviewing the incidents of my administration, I am unconscious of intentional error."

Normalcy — Warren G. Harding

Warren G. Harding makes another appearance on this list for popularizing the word "normalcy," the state of being normal.

Harding dropped the word in his famous "Return to Normalcy" speech, delivered as a candidate in the 1920 election in the wake of World War I.

Critics immediately pounced on the senator for using the word instead of the more popular "normality." The Daily Chronicle of London even wrote that "Mr. Harding is accustomed to take desperate ventures in the coinage of new word," according to Merriam-Webster's Kory Stamper.

What the critics didn't know is that "normalcy" was a perfectly valid English word dating back to 1857, less than a decade after the debut of "normality," according to linguist Ben Zimmer. But ever since 1920, the word has been indelibly linked to Harding.

Belittle — Thomas Jefferson

We can thank America's third president for introducing us to the word "belittle," meaning to make someone or something seem unimportant.

The earliest use of the word researchers have found was a 1781 writing of Jefferson's in which he said of his home state Virginia, "The Count de Buffon believes that nature belittles her productions on this side of the Atlantic."

Americans picked up on Jefferson's coinage in the coming years, and Noah Webster eventually included it in his first dictionary in 1806.

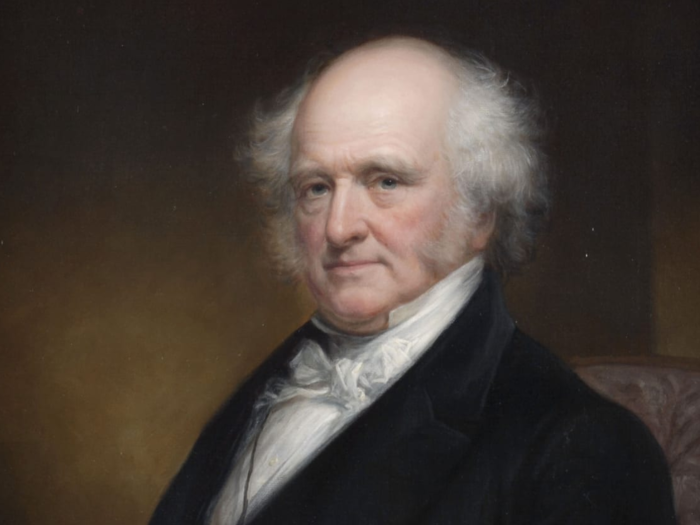

OK — Martin Van Buren

The word "OK" has a rich history, and eighth president Martin Van Buren played a major role in its lasting popularity.

There are a few explanations as to how "OK" came about, but the most popular one pegs it to an 1839 edition of the Boston Morning Post. That OK stood for "oll korrect," as in, "all correct" — apparently, it was a popular fad among educated elites to deliberately misspell things. Other jokey abbreviations of the era included NC for "nuff ced" and KG for "know go."

By the end of the year, OK was slowly making its way into the American vernacular, when Van Buren incorporated it into his 1840 election campaign. A native of Kinderhook, New York, Van Buren's nickname was Old Kinderhook, and as History.com explained, "OK" became a rallying cry among his supporters.

That election gave OK all the exposure it needed, and the word was cemented into our speech ever since.

Bloviate — Warren G. Harding

Somehow, one of America's least-heralded presidents managed to popularize yet another word that is commonly used today: "bloviate."

To bloviate is to speak pompously and long-windedly, something Harding readily acknowledged he did frequently. The president once described bloviation as "the art of speaking for as long as the occasion warrants, and saying nothing."

While bloviate sounds like it could come from Latin, it's actually just a clever coinage playing on the "blow" in words like "blowhard." And although Harding didn't coin it himself, he likely picked it up as a boy growing up in Ohio, where the word was most frequently used in the late 1800s.

Just like in the case of "normalcy," Harding came under plenty of fire from language purists when he made use of "bloviate," but most people wouldn't bat an eye at it today.

Fake news — Donald Trump

Fake news has been around as long as the news itself. But ever since Donald Trump took office, the term has experienced a shift in meaning.

While fake news traditionally refers to disinformation or falsehoods presented as real news, Trump's repeated use of the term has given way to a new definition: "actual news that is claimed to be untrue."

Trump's reimagining of fake news became so widespread in his first year as president that the American Dialect Society declared it the Word of the Year in 2017.

"When President Trump latched on to 'fake news' early in 2017, he often used it as a rhetorical bludgeon to disparage any news report that he happened to disagree with," Ben Zimmer, chair of the group's New Words Committee, said at the time.

"That obscured the earlier use of 'fake news' for misinformation or disinformation spread online, as was seen on social media during the 2016 presidential campaign," he said. "Trump's version of 'fake news' became a catchphrase among the president's supporters, seeking to expose biases in mainstream media."

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement