- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope is retiring after 16 years of incredible infrared imaging. It revealed nebulas and galaxies as we'd never seen before.

NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope is retiring after 16 years of incredible infrared imaging. It revealed nebulas and galaxies as we'd never seen before.

NASA launched the Spitzer Space Telescope in 2003.

Spitzer's instruments track infrared light between wavelengths of 3 and 180 microns. (1 micron is one-millionth of a meter.)

Measuring infrared light is useful for astronomers because light at those wavelengths can penetrate thick clouds of gas and dust better than visible light can.

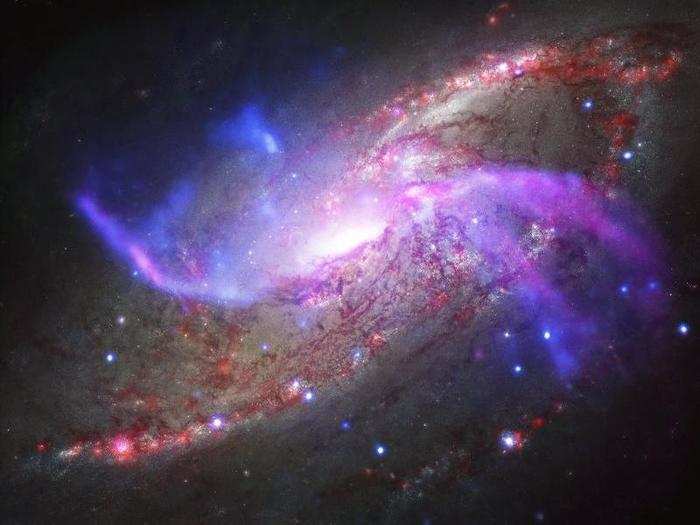

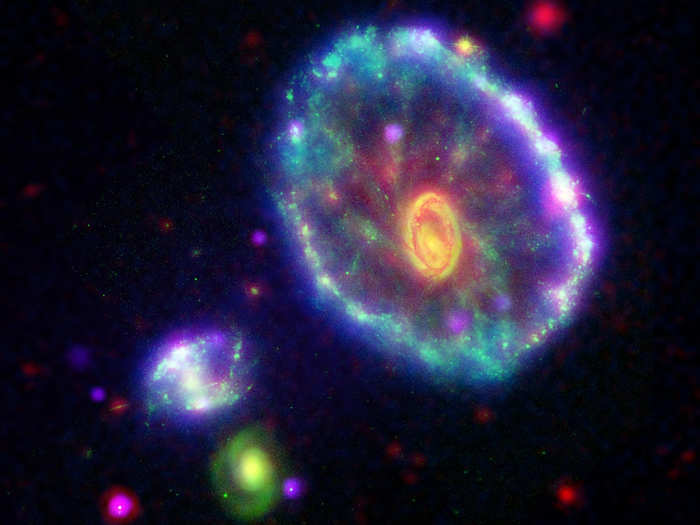

Spitzer has captured remarkable images of galaxies and nebulas.

Spitzer can even measure the bubbles of pressurized gas that indicate the creation of stars in nebulas.

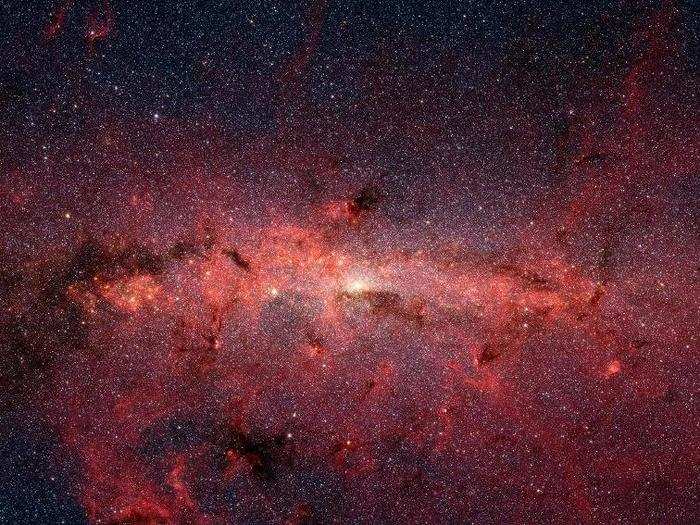

The telescope enabled scientists to see through the dust in order to photograph the center region of our own Milky Way galaxy.

Spitzer discovered the second-brightest star in our galaxy, the Peony nebula star (in the dusty and crowded center of this image) in 2008.

The Peony nebula star shines with the equivalent light of 3.2 million suns. The brightest star, Eta Carina, produces 4.7 million suns' worth of light.

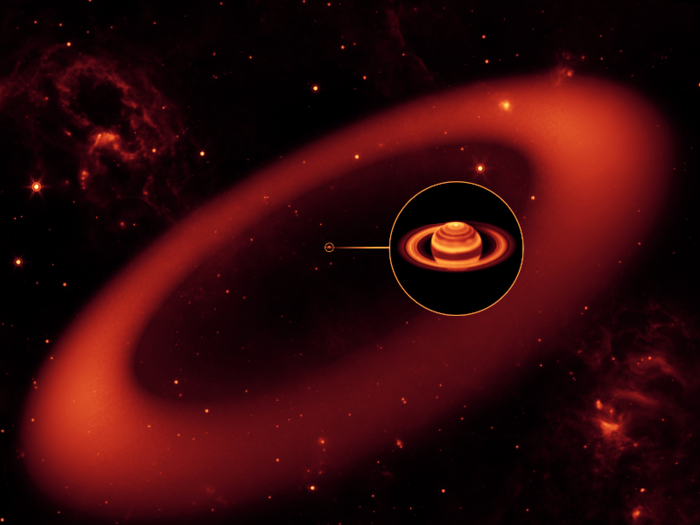

In 2009, the telescope led scientists to discover an additional ring around Saturn that's invisible to visible-light telescopes. The massive ring is mostly made of ice and dust.

The ring's diameter is equivalent to roughly 300 Saturns lined up.

Spitzer also found the oldest documented supernova in 2011.

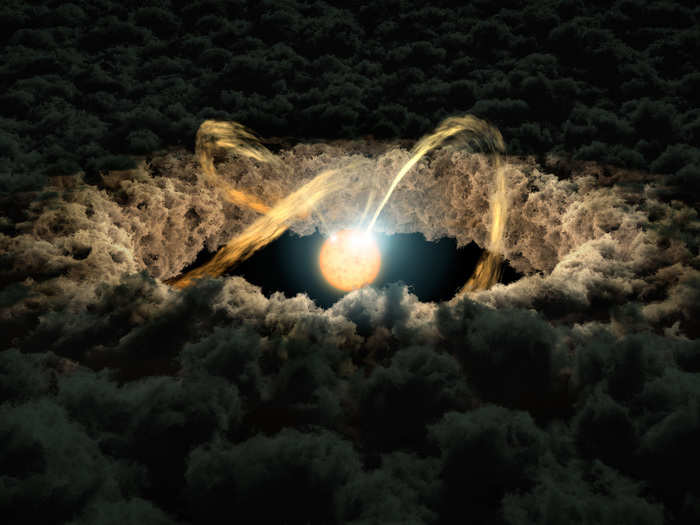

Then in 2016, data from Spitzer helped scientists determine the distance between young stars and their surrounding protoplanetary disks: rotating clouds of dense gas and dust.

A lot of stardust circles around newly formed stars. To determine how much, scientists used a method called "photo-reverberation," also known as "light echoes."

It works like this: Because some of a star's light hits the surrounding disk and causes a delayed "echo," scientists can measure how long it takes the direct light from the star to come to Earth and compare it to how long it takes the "echo" to arrive.

Technically, Spitzer completed its primary mission 11 years ago, since that was when it ran out of the liquid helium coolant necessary to operate two of its three instruments.

However, NASA engineers have been able to get creative to make the most of the one instrument still collecting data.

The telescope's passive-cooling design keeps it just a few degrees above absolute zero so as not to absorb any additional infrared radiation.

Spitzer trails Earth in its orbit around the sun, while also drifting away from the Earth slowly so as not to absorb any infrared radiation from Earth or the moon. (That radiation would mess with the other infrared-light measurements.)

That passive-cooling system is what allowed part of Spitzer's third instrument to continue operating for more than 10 additional years.

During that time, the telescope's infrared-light measurements helped facilitate the boom in NASA's hunt for exoplanets — the term for planets outside our solar system.

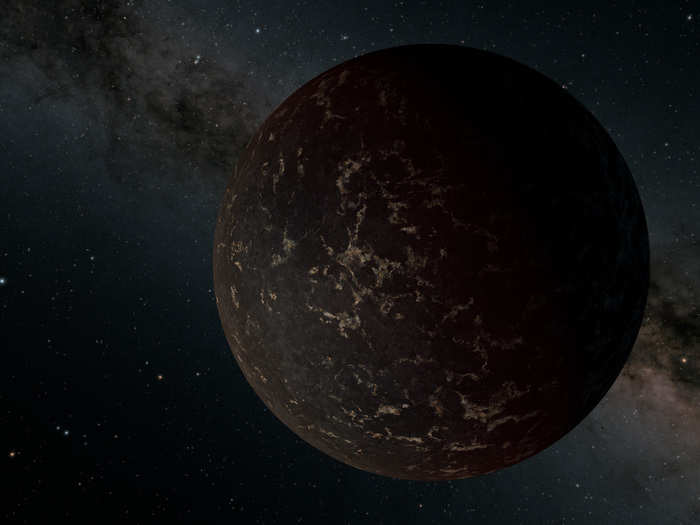

Spitzer's observations led to the discovery of planets around the TRAPPIST-1 star. We now know that the system's seven planets are all Earth-sized and terrestrial. Three appear to be habitable.

The first TRAPPIST-1 planets were discovered in 2016 using observations from Spitzer and from the planetary system's namesake, the ground-based TRAPPIST (TRAnsiting Planets and PlanetesImals Small Telescope) telescope in Chile.

Because different chemicals emit different amounts of infrared light, Spitzer's tools have also helped scientists study the chemical composition of objects in space.

Observations from Spitzer have shown, for example, that planets around cooler stars could hold life-forming elements like carbon and oxygen. Those M-dwarf and brown-dwarf stars are distributed throughout the Milky Way.

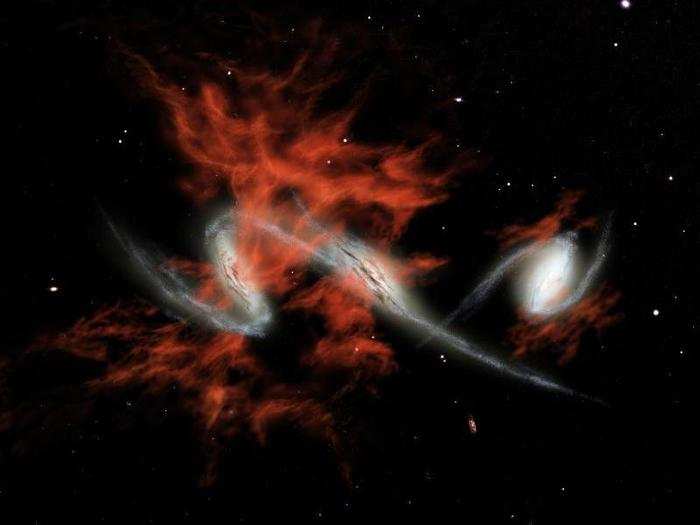

Some of the data Spitzer has collected, however, left astronomers with more questions. Giant galactic blobs, for example, remain a puzzle.

Astronomers can see the glow of these blobs through visible-light telescopes, but aren't sure of the source of energy that lights them up. Spitzer has collected data about the infrared light coming from them, but hasn't solved the mystery.

Even as the telescope enters retirement, astronomers will continue to mine such data sets for years.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement