- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- Lululemon founder Chip Wilson describes how he made the company's ex-CEO cry, slams Under Armour, and insults Diet Coke-drinking women, in a new tell-all book

Lululemon founder Chip Wilson describes how he made the company's ex-CEO cry, slams Under Armour, and insults Diet Coke-drinking women, in a new tell-all book

Wilson addresses his 2013 interview with Bloomberg, in which he said Lululemon pants "don't work" for some women's bodies. Wilson writes that the "catastrophic" interview "ruined" him.

But Wilson still stands by his belief that pilling problems with Lululemon's leggings were caused by women squeezing into pants that were too small.

Wilson writes that his comments were misinterpreted and "what was simple was made scandalous."

"With the pilling, what I eventually discovered was that some women were buying the pants two to four sizes smaller than necessary, with body shaping in mind," he writes. "If enough stress is placed on any object, fractures will occur."

Wilson also suggests that The New York Times might have accepted a bribe in return for publishing a negative story about Lululemon in 2007.

The Times wrote a story in 2007 accusing Lululemon of making false claims that its clothing contained seaweed. The story cited lab testing as evidence that the claims were false.

"When I read it, my first thought was that it was mean-spirited," Wilson recalls in the book. "Lululemon was all about love so I couldn't imagine why someone would ever write something like that."

Wilson says he wouldn't doubt that a short-seller paid the Times to write the story.

If "short sellers want to ensure profits, then the smart ones will manufacture a false story that will impact the stock," Wilson writes. "There is so much money to be made I wouldn't doubt a backroom payoff to the writer."

Throughout the book, Wilson is highly critical of Lululemon's former CEO, Christine Day. He claims that after the sheer-pants recall, he told Day in a meeting that she was a "terrible CEO." He alleges that she "fake" cried in response.

Wilson said he and Day repeatedly clashed.

"Christine was adding value to Lululemon's stock by trimming expenses and testing the upper limits of what we could charge for our product," Wilson writes. "We were giving Wall Street stock analysts everything they wanted, but I worried that our foundation was getting weaker by the moment."

Day has also spoken publicly about clashes with Wilson.

In what he called an attempt to "re-establish a working relationship with her," Wilson says he met Day in her office in mid-April 2013.

"As I saw it, we needed to clear the air," he writes. "In some ways, this difficult, cut-the-s--- conversation had been a long time in the making."

"I looked at her and said, 'Christine, you put a lot of good things in place for Lululemon, but you never had a vision for the company. ... In my mind, you're a world-class chief operations officer. But you're a terrible CEO.'"

According to Wilson, this comment made Day cry.

"She just cried and turned away — a reaction I thought was unprofessional and likely fake," he wrote. "Charade or not, the next day, Christine announced her resignation to the board."

Wilson also shares his views on how birth control shaped generations of women. He says that he believes the birth control pill led to higher divorce rates because "men had no idea how to relate to this newly independent woman."

With the birth control pill, "women suddenly had significant control over conception," Wilson writes.

"If they did want children they could decide when, and how many. There was a newfound sense of independence in this ability to delay children. There was also the opportunity to pursue careers that had, to date, been dominated by men. Meanwhile, men's lives did not change with the arrival of the pill, and they had no idea how to relate to this newly independent women. Thus, came the era of divorce, with divorce rates peaking in the late seventies and early eighties."

As divorce rates soared, many of these newly empowered women — whom Wilson refers to as Power Women — entered the workforce. Hormones in their birth control pills, along with their "three-martini lunches," contributed to rising rates of breast cancer, Wilson says.

High hormone dosages in birth control pills "combined with the Power Women's lack of sleep, work-related stress, poor eating habits, and three-martini lunches worked together to cause the terrible using in breast cancer rates in the nineties," Wilson writes. "Too many Power Women had looked to their fathers to define business success, emulating both their drive and toxic lifestyles. Regretfully, for many Power Women, this would ultimately cost them their health and, in some cases their lives."

Wilson defines women throughout his book as one of three types: Power Women, Super Girls, and Balance Girls. He says these categorizations helped him understand and target different market segments.

Power Women are divorcées who came up through the sexual revolution and "put in 12-hour work days, kept a clean and orderly home, and did their best to give their children all the love they'd had pre-divorce," Wilson writes. These women also gave up their social lives and sleep, he says.

Super Girls are the daughters of Power Women. They are Lululemon's target customers.

"I defined a Super Girl to be 32 years old and born on the 28th of September. I called her Ocean. Each year, since 1998, Ocean never got a day older or a day younger," Wilson writes. "Every Ocean in the world would be our sponsored athlete, just like Nike chooses a few specific men to sponsor."

Super Girls' "utopia" is to be a"fit 32-year-old with an amazing career and spectacular health," Wilson writes. "She was traveling for business and pleasure, owned her own condo, and had a cat. She was fashionable and could afford quality. At 32, she was positioned to get married and have children if she chose to and to work full-time, part-time, or not at all. Anything was possible."

Balance Girls are the same age as Super Girls. They are "type-A Wall Street personalities" that sought jobs at Lululemon to find a better balance in life. But they clashed with the company's culture, Wilson says.

"They had been working 14-hour days in finance, were not dating, and could see no prospects for marriage or children," Wilson writes. "Utopia for these women was to be zenned out, but this was not Lululemon. We soon had to rid ourselves of these Balance Girls."

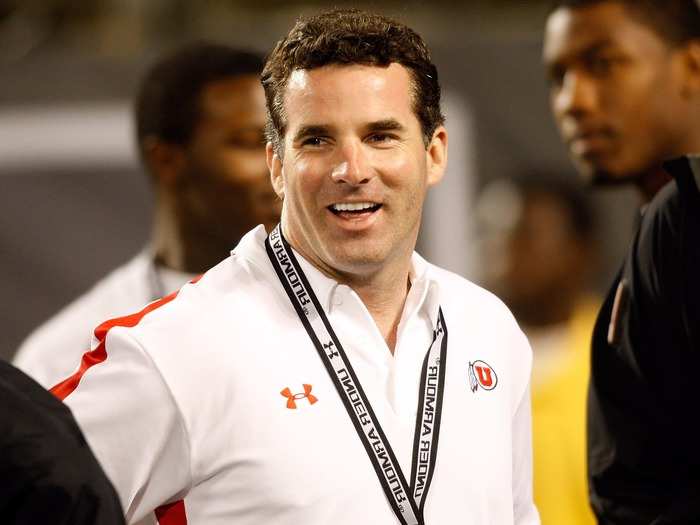

In 2008, Wilson considered buying Under Armour. He decided, however, after a meeting with Under Armour CEO Kevin Plank, that Plank's "macho philosophy" and Under Armour's image of "male chauvinism" would clash with Lululemon's Super Girls, he writes.

Wilson writes that he considered buying Under Armour when the company "was still making garments with big logos for impressionable teenage boys and insecure men."

"However, after a meeting with Under Armour CEO Kevin Plank in 2008, I couldn't see Kevin’s macho philosophy working with that of the Super Girls," he said. "Under Armour, I thought, had an in-your-face image of winning at all costs, male chauvinism, and leaving everybody else in the dust."

Wilson also reveals that Victoria's Secret, Liz Claiborne, and Gap expressed interest in buying Lululemon. Gap's offer was too low, and the company was "sucking on all cylinders" with stores that looked like "bowling alleys," he writes.

Victoria's Secret sent a letter to Lululemon in 2004 expressing interest in the company, Wilson said.

"We were flattered, but it didn't take us long to agree that wasn't a direction we wanted to go," he writes in the book.

A couple years later, Liz Claiborne offered to buy Lululemon for $500 million, with $100 million to be paid out each year over five years. Wilson said he turned down the offer in part because because the company's culture was too "corporate."

Gap later made an offer of $200 million for a full buyout, he said. Wilson called this amount "inadequate."

He also criticized the company, saying it was "sucking on all cylinders" at the time and that "their stores looked like bowling alleys."

While some companies were showing interest in purchasing Lululemon, soda giants Coca-Cola and PepsiCo were threatening to "drown" the company in lawsuits, Wilson writes.

In 1998, Wilson wrote a manifesto that served as the founding principles of Lululemon’s culture. The manifesto was put near the cash register and in 2003, it was being printed onto every bag. One of the tenets of the manifesto declared: "Coke, Pepsi, and all other pops will be known as the cigarettes of the future. Great marketing, terrible product."

Coke and Pepsi later "threatened to drown Lululemon in lawsuits," he writes.

The company removed the statement from its manifesto in response. Wilson said he believes that decision was part of a years-long dismantling of the culture that he had established at Lululemon.

This belief was reinforced for Wilson when he started seeing Coke and Pepsi cans around Lululemon's office. He writes that he tried to ban the drinks from the company's headquarters.

Wilson recalls Lululemon's early days in the book, and says he was willing to do anything — including digging through dumpsters — to help the company survive.

Wilson writes that when he needed to find a manufacturer of yoga mats for Lululemon, he didn't know where to start. So he ventured into a back alley behind a mat supplier.

There, he found a cardboard box with a return address on it, and he traced the address back to the supplier's manufacturer.

Wilson also discusses how he wanted to move Lululemon's side seams to the back of the pants to "frame the bum and make the bum appear smaller" because men would find that attractive.

"I believed that eventually, men would tell women the pants looked great without really understanding why," he writes.

The key invention behind Lululemon's success, Wilson writes, was getting rid of problems with "camel-toe." This gave rise to the trend known as athleisure.

"Solving the camel-toe problem was probably the key invention," because it enabled women to wear Lululemon's pants outside the gym, Wilson writes.

As an increasing number of women began wearing leggings outside the gym, the athleisure trend was born.

Wilson surprisingly hates the term "athleisure." "To me, athleisure denotes a non-athletic, smoking, Diet Coke-drinking woman in a New Jersey shopping mall wearing an unflattering pink velour tracksuit," Wilson writes. "Too much leisure, too little athletics."

Wilson is credited with founding athleisure, a fashion trend in which clothing designed for exercise is worn outside the gym.

But Wilson says he strongly dislikes the term. He prefers "street-nic," a term he came up with in the 1990s to describe the intersection between streetwear and technical apparel.

In another surprising twist, Wilson reveals that despite building a women's clothing empire, he doesn't like wearing clothes. This explains why some colleagues recall finding Wilson shirtless in his office or driving around in his car.

"Everything about clothing bothers me," Wilson writes. "If I could spend the rest of my life in a Speedo I probably would."

This frustration with clothing spawned Wilson's fascination with how different materials fit and feel on the body, which ultimately led, in part, to the creation of Lululemon's first pair of leggings.

It also explains why some colleagues recalled finding Wilson shirtless in his office or driving around in his car.

"When I first walked into the office, all I remember is this big West Coast dude sitting on a yoga ball, shirtless, in board shorts and flip-flops," former Lululemon consultant George Tsoga is quoted as saying in the book. "His first words were, 'You're way too serious, do not wear a suit again to this office.' That was my first taste of Chip's unique culture."

Not one to shy away from controversial topics, Wilson also shares in the book that he isn't entirely opposed to child labor, writing, "working young is excellent training for life."

"In North America, I noticed that there were some kids not made for school, who dropped out with nowhere to go," Wilson writes. "In Asia, if a kid was not 'school material,' he or she learned a trade and contributed to their family. It was work or starve. I liked the working alternative."

Wilson says that his own children have worked in the family business since the age of five with no pay.

Overall, Wilson says he's proud of Lululemon's success, but laments that it's "now a company that doesn't take risks."

Wilson, who is no longer involved with Lululemon, says the company's success is only a fraction of what it could be.

"The bar for what is great has been reset to a level of mediocrity, but we can raise it once again," Wilson writes. "Good is the enemy of great."

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement