- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- I spent 2018 speaking with CEOs, billionaires, and a Nobel laureate, and there are 15 lessons I just can't seem to forget

I spent 2018 speaking with CEOs, billionaires, and a Nobel laureate, and there are 15 lessons I just can't seem to forget

From 'This Is Success,' I learned that it can be worth the risk to take a role outside your comfort zone

And that at some point, you have to step away from the details

Alli Webb turned a hairstyling side project into Drybar, a thriving salon business with more than 100 locations across North America. She did this with the help of her designer husband Cameron Webb and her marketer brother Michael Landau.

Because Webb saw her personal project evolve into a full-fledged business, she had to deal with letting go of responsibilities and gaining new ones. She said that becoming comfortable with stepping back from details and focusing on tasks she was better suited for at that point in her career was the most important advancement she's made in business.

"If I'm being totally honest, there's times that I don't agree with all the decisions that are made, and that is a really hard pill to swallow," she told me. "But it's like, we have to keep going, and we have to learn from our mistakes, and we have to look back and say, 'You know what, we should have done this differently, but here we are.' I think that's all part of the learning and growing process.

I also learned that confidence is a skill, like anything else

Ryan Serhant is not only the star of the popular show "Million Dollar Listing"; he's one of America's most successful real estate agents. His team closed more than $800 million worth of deals last year.

Serhant exudes confidence, and it's been key to closing deals and landing big-time clients. But, he told me, he spent most of his life awkward and shy.

When he moved to New York after college, he went from struggling actor to broke real estate agent. One day he decided he was going to do what it took to be a successful agent.

"I was forced to develop a thicker skin and to come out of my shell and really try to create a personality that was OK with talking to strangers, which totally freaked me out when I first moved to New York," he told me. "And I think that that kind of ability of mine to just go up to anybody on the street and ask them their name and how they're doing, without feeling any shame whatsoever, has really helped me in my sales business."

And that no one's problems are completely unique

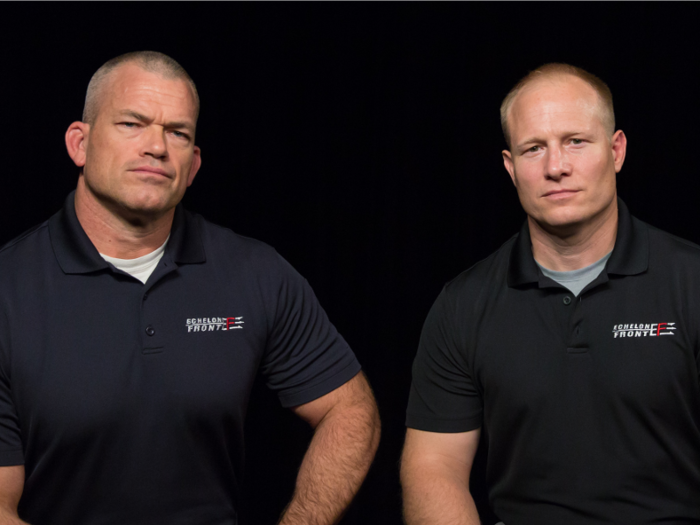

Jocko Willink and Leif Babin are former Navy SEAL commanders and the authors of the book "The Dichotomy of Leadership."

Through their company Echelon Front, they and their team have worked with around 400 companies since launching in 2010. They told me that there are two mistakes new leaders almost always make, and they apply to ambitious people who don't necessarily have to be in management roles: They think they have to know everything from day one, and they think their problems are unique.

Both are dangerous because they can not only lead to distracting anxiety, but can cause leaders to start blaming others when things don't go as planned, rather than accepting their circumstances and seeking help from those who have already dealt with the challenges they're facing.

I also had a chance to interview Willink for the podcast, and he shared an insight that seems too simple to have any value, but it's what helped me get through the New York City Marathon in November after getting a painful injury at mile 7.

SEAL training is tough, Willink explained, but there's nothing especially profound about it. If you're there, you have the physical capability of finishing it, but the reason the vast majority of trainees don't pass is because they quit when their pain or discomfort becomes something they decide they don't want to tolerate. "There's the big lesson: Don't quit."

I also heard stories of how success is based on the relationships you build starting in your earliest days

Several years ago, Larry Morrow was a college dropout looking to make money off his party business. Now, he's got a New Orleans-based event planning company with clients like Drake and Mary J. Blige, and a restaurant that's been lauded in the press.

The 27-year-old entrepreneur told me that all of it is based on relationships. "I've built a reputation for producing great events, and for just taking care of people," he said.

The reason he was able to pull in a client like Diddy, for example, is because of the way he treated his earliest clients, who may have been just on the fringes of celebrity.

And that the most successful entrepreneurs thrive on control — even if they're controlling their own failure

There's a certain subculture online of "influencers" who suggest that quitting your job and starting your own company is a move that can make anyone happier. But after countless conversations with entrepreneurs, it's clear to me that is horrible advice, and that the myth of a "born entrepreneur" is actually much closer to the truth.

Eddy Lu, the cofounder and CEO of the high-end sneaker retailer GOAT, proved this to me.

Lu and his cofounder Daishin Sugano left their jobs in finance to first work on various app businesses before trying their hand at a cream puff franchise. All of them flopped, and as the franchise business was sinking, Lu said he had, "Every kind of debt possible. I was in credit-card debt, in debt to my ex-girlfriend, my girlfriend at the time. It was a lot of pain. I would wake up in the middle of the night with just pangs of guilt, and I was scared, yeah."

But, like so many other entrepreneurs I've spoken with, he'd rather live in that space, in control of his own business, than work for someone else. "To be honest, going back to a big corporate job just was probably worse than that."

I heard, somewhat refreshingly, that planning out your career path in detail is a pointless exercise

You may know Bethenny Frankel from her role on the wild reality show "Real Housewives of New York City." But what you may not know is that she's used it to help her build a $100-million Skinnygirl branding empire.

Frankel never set out to become a reality show star, she told me, but she's used it to her advantage as an entrepreneur. Her best advice: Don't spend time on a detailed career path because there's no way it's going to work out, and if anything, it will prevent you from taking risks that will work to your benefit.

"I would say to be on the road, start the journey, and get dirty, and clean yourself off, and take another path," she said. "Get locked out, and find a way to climb in another way. You've got to get on the road and figure out what it is that you want to do, what value you add, what clicks, what doesn't."

You can use the simplest questions to guide your career

Adena Friedman started at Nasdaq as an intern in 1993, and aside from a brief stint away from the company, she's spent almost her entire career with the stock exchange on her path to the top.

She developed a simple mantra she told me she's used as a guide: "Have I achieved everything that I could have achieved with the skills that I have? Have I brought my best self to the job every single day and do I treat every day as day one?"

Simple, but effective.

I was informed that leaders don't belong on a pedestal

Stanley McChrystal retired as a four-star general in the US Army in 2010, and is best remembered for revolutionizing the way America runs its special operations, leading to the assassination of al-Qaeda in Iraq leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.

In his book "Leaders," McChrystal said that we must abandon the idolatry of leaders. Even when we don't like our leaders, we tend to put them on a pedestal, he said, and that impedes progress.

"Leaders have a role, but the followers have a huge role, huge responsibility," he told me. "Huge responsibility in doing their part, but also shaping the leader. You see the leader making a mistake and you don't say something to them? You fail in your job. And then when you see them fail and you get smug and you go, 'Yeah, I thought that she was never that good, he was never that good,' shame on you."

And that we need to cherish the journey, because achieving a goal is fleeting

Peter Diamandis is a serial entrepreneur best know for his work in space exploration and for being the founder of the XPrize.

He told me that when he witnessed the successful space flight in 2004 that he supported through the X Prize, he had helped fulfill more than a decade of work.

"And I remember that moment," he said. "I have a mental image of what's going on. The ship had just gone to space successfully, against all the odds, and landed. And I felt like I was at the top of a mountain I had just climbed for 11 years. I remember, when I looked around, all I saw were higher mountain peaks. So it's this interesting realization that it is the journey, not the destination."

From reporting on Better Capitalism, I learned that Americans are living in a second Gilded Age

It's been a decade since the Great Recession made inequality in America a mainstream topic of discussion, and even though the economy has been doing well this year, the gap between the 1% and the rest of the country is among the largest it's ever been.

HW Brands, a historian at the University of Texas at Austin and the author of "American Colossus," said it's because we're at a point that can reasonably be called a second Gilded Age, a reference to the period between Reconstruction following the Civil War and the beginning of the Progressive Era of the early 20th century.

Brands has a helpful metaphor for understanding the reasons for both of these ages. "Tension between capitalism and democracy has characterized American life for two centuries, with one and then the other claiming temporary ascendance."

He believes that the only ways we'll emerge from this current state of vast inequality will be the same as before, through a major war or a mass embrace of progressive policies that reduces the power of corporations and the elite.

"As long as people are free to make that case and as long as people are free to vote for or against that, then I think democracy will make a comeback," he said. "I think the pendulum swings and it's going to swing back."

But companies don't have to be charities to do good

Saying that major companies will make decisions for the benefit of society might sound good, but none would ever make that decision if it would cost them profits — they're not charities, after all.

But Boston Consulting Group senior partner Wendy Woods said they don't have to be. At this point in America, it makes sense for companies to embrace initiatives focused on ESG (environmental, social, governance) criteria.

"And I think total societal impact allows us to get to a different place where, we are saying, this is not just about business being a checkbook, this is about business finding ways to do 'better capitalism' and to do their job of creating shareholder value," she told me, referencing our series.

BCG conducted an in-depth report on the effects of ESG initiatives, and found that companies embracing them have grown their bottom lines more than those that haven't. To give an obvious example of why this makes sense, sustainability programs not only benefit the environment, they reduce costs.

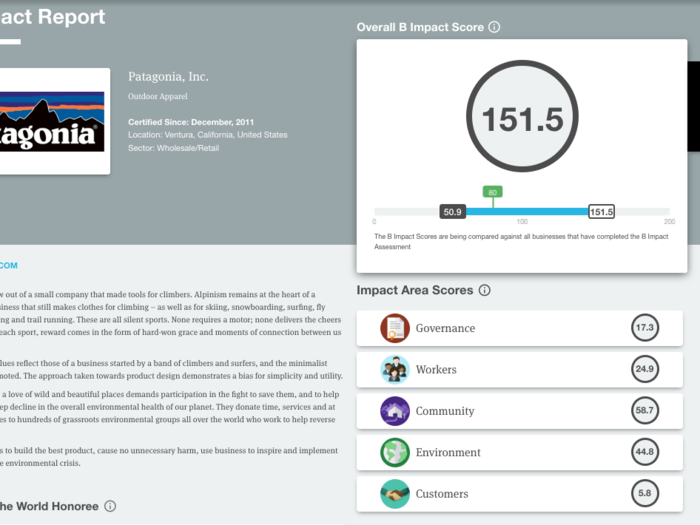

Companies that embrace B Corp status can use it to attract both customers and employees

Jay Coen Gilbert, a cofounder of the AND1 basketball apparel company, found a way for companies to verify and advertise their dedication to socially conscious programs through "B Corp" status, with the B standing for "benefit."

Coen Gilbert's company, B Lab, analyzes companies that apply for B Corp status, and grants them the accreditation if they meet a certain threshold for the ways they benefit workers, customers, communities, the environment, and their shareholders. There are now 2,600 B Corps around the globe.

Danone is one of the largest food companies in the world, and its North American subsidiary is the largest certified B Corp. Danone CEO Emmanuel Faber told us that the certification had received tremendous employee support and won over skeptical investors, and noted that Danone's plan helped it renegotiate a 2-billion-euro syndicated banking loan with 12 major banks at a lower cost.

"So this is basically recognizing the fact the credit rating of Danone is better as a B Corp than not being a B Corp," he said. It's why he plans on having all of Danone get the certification by 2030.

And business leaders and investors are also increasingly looking beyond Silicon Valley and New York

AOL cofounder and former CEO Steve Case is the head of the Rise of the Rest, a movement that includes an impressive network of the country's most influential investors and businesspeople investing millions of dollars outside of Silicon Valley, New York City, and Boston, where 75% of venture capital goes.

"These are national scale, maybe even global scale companies," Case told me, referring to companies he's invested in across the country. I joined him on part of one of his exploratory bus tours in May. "They just happen to be in Louisville, they happen to be in Chattanooga, so they shouldn't just have regional ambitions. They can go the distance."

I explored a related project, but with a more focused scope and larger financial scale, when I went to Detroit to see Quicken Loans founder Dan Gilbert's $5.6-billion project that has transformed the city's once vacant downtown.

Amazon may have dominated the news cycle for weeks with its selection of New York and northern Virginia for its dual second headquarters, but you should expect to hear an increasing number of stories about developing the American cities that were left for dead in the era of deindustrialization.

Encouragingly, it looks like the reign of toxic short-termism may be coming to an end

In the wake of the Great Depression, British economist John Maynard Keynes published his revolutionary book "The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money." He differentiated between short- and longterm value, and noted that the American markets were designed to encourage the former over the latter, at the expense of society.

Economists who pushed against Keynesian policies in the 1960s and '70s, most notably Milton Friedman, believed that trying to incorporate societal good into a company's mission was foolish, and that the only way to truly benefit all stakeholders was to focus solely on making choices that created value for shareholders; the rest would fall into place.

Friedman's ideas took hold in the 80s, most notably in the United States. They were further cemented through judicial precedents establishing shareholder primacy as the fiduciary responsibility of public companies. There was a rise of activist investors, and Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz told me this all led to the reign of toxic short-termism.

The reason he thinks the tide has been shifting away from Friedman's lens, with leaders like BlackRock CEO Larry Fink proclaiming he will not do business with companies that lack a clearly defined purpose beyond the abstraction of increasing shareholder value, is because of a survival instinct, at a time when overall GDP growth is much slower in the last two decades than it was between the end of World War II and 2000.

It's an old debate about business' role in the world, and the balance is shifting once again.

"As they said in the Bible, 'There is nothing new under the sun,'" Stiglitz said, laughing. "But there is a new context to it today."

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement