- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- Countries in Asia are looking for ways to counter China's growing power - with and without the US's help

Countries in Asia are looking for ways to counter China's growing power - with and without the US's help

'Hugging America'

External balancing

"There's increasingly this new form of defensive policy taking place in Asia, which doesn't really rest in mutual defense treaties but rests in deepening defense partnerships through extensive bilateral exercises, through arms transfers, which are a sign of the strategic weight of an emerging relationship, and other means that countries are pursuing to diversify" their defense networks, Lemahieu said.

A kind of external balancing, in which smaller players band together, is starting to emerge.

"It's developing, and it's unproven," Lemahieu said. "So there's a degree of depth there, but it could be stronger."

Based on regional non-allied partners, another subcategory in the defense-networks measure, Singapore is far ahead, with a score of 100. The US, with a score of 73.9, ranks fourth, behind Australia, with 90.4, and Malaysia, at 83.2.

"Smaller countries, like Singapore, they do very well at this," Lemahieu told Business Insider. "They have to. They're small. They're vulnerable. They need to be investing in their defense networks."

"But even traditional allies of the United States, like Australia, have started hedging against the prospect of a possible US retrenchment from the region," he added. "It's a reality in the mind of a lot of allies, who traditionally have formed part of this hub-and-spoke system surrounded by the United States — i.e. their relationship with other US allies has been really precipitated through Washington, DC."

Australia and Japan are deepening their defense ties, and New Delhi, even with its growing ties to the US, is increasingly working with its neighbors, including its first-ever naval exercises with Vietnam and closer cooperation with Indonesia, which may let India use the deep-sea port of Sabang, at the western edge of the strategically valuable Malacca Strait.

"So in that way you see that the countries are pursuing different routes by which they wish to hedge China's rise," Lemahieu said.

Internal rebalancing

Some in the region have looked inward to adjust to external developments.

"Other countries, like Japan, are really investing in their own, reinvigorating their own military capability or reforming the constitution, like [Prime Minister Shinzo] Abe has tried to do," Lemahieu told Business Insider. "That's also been called internal rebalancing by the Japanese."

Japan disarmed after World War II, but in recent years, amid growing tensions in the region, Tokyo has moved to rebuild its armed forces and take a more assertive role abroad.

In 2014, Japan lifted a ban on military exports, and in the years since, its defense contractors have grown more interested in overseas sales. In 2015, parliament approved a law allowing Japan's military to mobilize overseas under certain conditions. The country's 2017 military budget was its largest ever.

More recently, Tokyo added a centralized command and amphibious forces to its Ground Self-Defense Forces, in what was the largest reorganization since the JGSDF was formed in 1954, according to The Diplomat. Earlier this year, Abe's party adopted his proposal to revise the constitution, modifying its prohibition on maintaining military forces — though that effort faces political obstacles and public opposition.

Acquiesce

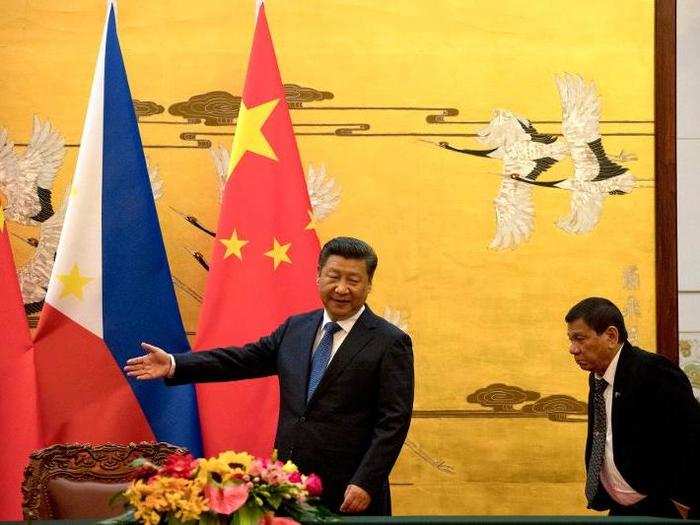

"I think the fourth form of dealing with China's rise is not to hedge or even to hug America, but to acquiesce," Lemahieu said. "A number of countries, including perhaps the Philippines under ... under [President Rodrigo] Duterte, seem to almost have acquiesced to the idea that China is now a dominant military player in the South China Sea, and all but given up the pretense of wanting to hedge."

The Philippine military maintains a close institutional relationship with the US military, Lemahieu noted, and Manila has pushed back on some Chinese actions, including the naming of undersea features in Philippine territorial waters and the landing of Chinese bombers on disputed parts of the South China Sea.

But Duterte has made a political shift toward Beijing, though he and President Donald Trump appear to get along. He has justified Chinese military outposts in the South China Sea, saying they were meant to defend against the US, and China has also offered the Philippines aid and weapons. (The US has blocked the sale of arms to Manila over human-rights concerns.)

Duterte has also fended off claims he is abandoning a 2016 international-court ruling that found China had violated the Philippines' sovereign rights in its exclusive economic zone, which stretches 200 nautical miles from its shores — though Duterte has said the Philippines should set aside its dispute over maritime control to carry out joint exploration with Bejing.

The balance of power is not set, and countries in Asia still have the ability to reshape it in the future.

"There's a range of reactions that we're seeing taking place, and for that reason I think it's hard to predict the balance of power in Asia," Lemahieu cautioned.

"We can measure resources. We can measure influence, but it really depends on these choices, these policy initiatives by larger countries, like the US, in terms of maintaining their commitment to staying in Asia, but then by a number of smaller countries, middle powers, in terms of their decisions to either acquiesce to China or to form a strategic counterweight," he added. "We see signs of both taking place in Asia."

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement