- Home

- slideshows

- miscellaneous

- 15 culture clashes I've had as an American traveling in Asia

15 culture clashes I've had as an American traveling in Asia

1. In Japan, China, and Korea, you need to carry business cards because you exchange cards whenever you meet a new acquaintance.

2. Using Uber, Grab, or other ride-hailing services is a very big faux-pas in Bali.

In Bali, ride-sharing apps like Uber and its Southeast Asian counterparts Grab and Go-Jek were once tourists' first choice to get around the island.

But taxi drivers have said ride-hailing services violate Bali's unwritten traditional laws and profit off their communities, while not giving back. Taxi fares in Bali are double ride-hailing services, but over 30% of their income goes to the community to build roads and pay for services the government won't provide.

Many tourists use ride-hailing apps anyways, but local Balinese in certain areas will ask you to refrain.

When I first arrived on the island, I scoffed at the idea of not using Uber or Grab due to a "taxi mafia." By the time I left, I was sympathetic to how technology has completely disrupted Bali's way of life.

3. Few people in major cities in China still use cash in their day-to-day life — and some places don't even accept it.

Paying with your phone isn't a novelty in China these days. Paying with cash is.

Tencent and Alibaba's competing mobile payment apps — WeChat Pay and AliPay, respectively — are used by just about everyone in China, from fancy restaurants and high-end designer boutiques down to street vendors, taxi drivers, and even panhandlers.

Ninety-two percent of people in China's top cities said that they use WeChat Pay or AliPay as their primary payment method, according to a 2017 study by Penguin Intelligence.

Read more: One photo shows that China is already in a cashless future

As foreigners can't use AliPay or WeChat Pay — you need a Chinese bank account to sign up — I had numerous issues paying for things in China's big cities.

One coffee shop in Beijing didn't even have a register, only a QR-code scanner. When I tried to hand the barista cash, he looked at me, confused: All they accepted was mobile payment. I had to leave and go to a different cafe.

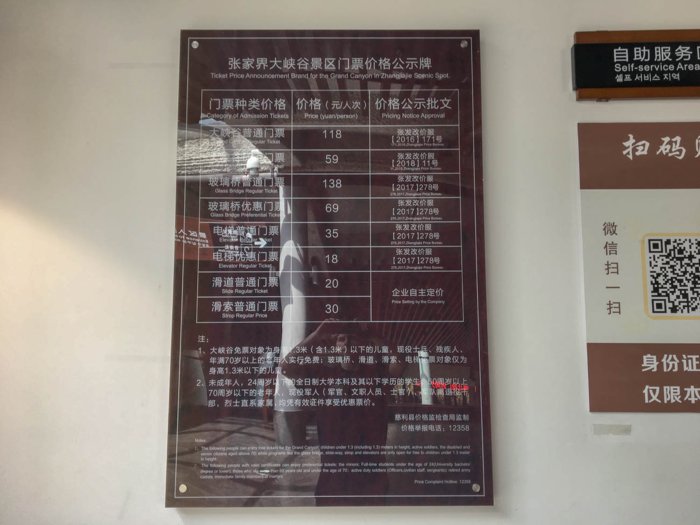

4. Very few people in China speak English.

Visiting China as a Western tourist isn't easy.

Around 10 million people out of 1.3 billion in China speak English, according to The Telegraph. That's less than 1%. Good luck finding them outside of major cosmopolitan cities like Beijing and Shanghai.

The lack of English extends to signage, tourist attractions, hotels, taxi drivers, and every other part of the culture a tourist is likely to encounter. Add in that Mandarin Chinese doesn't translate well to English via Google Translate and the general lack of American tech services like Google and Facebook (or English-language versions of popular Chinese tech services), and it can be exhausting.

I traveled with my partner, who is Chinese-American and speaks fluent Mandarin. We still encountered plenty of confusion, be that taxi drivers taking us to the wrong destination or misunderstanding the rules at tourist sites. Be prepared.

5. If you want to get something done in business, you have to become friends first.

In China and Korea, business culture is guided by social relationships, a concept known in China as "guanxi."

While there are many ways to explain "guanxi," the easiest (and most simplified) is to say that it is the web of social relationships that you build up between family, friends, and business acquaintances through reciprocal favors.

Tourists aren't likely to run into "guanxi" too much, but those traveling for business need to understand the concept. In China, especially, ongoing personal relationships must be developed in order to complete business deals. That can mean lots of dinners, nights out drinking, and favors.

At times, I found myself stumped in China to get a source to respond to an email or a question. When a friend with "guanxi" with the person asked for me, doors opened. Unresponsive public relations reps were suddenly willing to help me with every aspect of my reporting trip.

6. Because of the need to maintain social standing or reputation, it is rude to ask new friends or business partners for things directly, to criticize someone in front of their peers, or to contradict or upstage someone.

The concept of "face" is essential to understanding China, Korea, and many other Asian countries. Like "guanxi," "face" is hard to translate, but it basically means your reputation in relation to your community, as determined by dignity, prestige, and social status.

While Westerners don't need to worry too much about their own "face" when visiting China or Korea, understanding the concept can help in business.

Americans and other Westerners tend to ask questions and negotiate directly. East Asians operate more slowly in business, will drag out negotiations, and try to achieve consensus with their peers. When Westerners push for "yes" or "no" answers or criticize, contradict, or otherwise upstage an East Asian business acquaintance, they are likely causing that person a "loss" of "face," which will consequently harm the relationship.

I had more than a few awkward moments in boardrooms with Chinese executives or dealing with public relations representatives where I forcefully pushed for a "yes" or "no" answer that made us both look bad.

7. In China and many other East Asian cultures, it is considered rude to maintain direct eye contact in a conversation.

As an American, I have become used to keeping eye contact with the person with whom I'm having a conversation. To look away would indicate shiftiness or untrustworthiness. In most East Asian cultures, it means something completely different.

I first noticed this in China when I was conducting interviews with people in the tech industry. The more I kept eye contact, the less they wanted to talk. It was clear that my intensity and directness was making them uncomfortable. I had to dial myself back to fit in better with the culture.

In Asian cultures, direct eye contact can be considered rude, an insult, or a challenge. Rather than being seen as confident — how direct eye contact is read in the US — it is seen as confrontational. As Harvard Business Review has written, direct confrontation is seen as "immature" and tactless in East Asian cultures.

8. With over 1 billion people, people in China have a different understanding of personal space than Americans do.

There are a lot of people in China — roughly 1.3 billion. For a Westerner in China, it can be very overwhelming to go to places like train stations, the subway during rush hour, or major historical sites.

The mass of people means that the Chinese concept of personal space is very different from the American perspective. Entire families may live in tiny apartments and you are almost always standing shoulder-to-shoulder in a crowd. With so many people vying to get into a subway car or into an elevator at all times, there is no option but to pack in like sardines.

Unless I wanted to wait around forever to get anywhere, I had to get with the program. It was shocking at first and I suffered more than a few bouts of claustrophobia.

9. In China, it is very strange to hug friends or new acquaintances hello or goodbye, though that's starting to change among younger generations.

Like many Westerners, I'm a hugger. Shortly after meeting someone in a personal setting, I offer up hugs as a way to say hello or goodbye. Chinese people — and most East Asians, for that matter? Not so much.

In traditional Chinese culture, hugging is not acceptable, particularly between those of the opposite sex. As Yang Chunmei, a professor at Qufu Normal University, has written, "public displays of affection are a source of embarrassment." Even among spouses, hugging, kissing, or holding hands in public is odd.

While I knew this before visiting China, it is difficult to eschew a long ingrained cultural practice. There were many moments during my six weeks in China where I awkwardly went in for a hug with a new acquaintance and then had to pull back, and extend my hand for a handshake instead.

10. In China and Korea, it's common to ask personal questions about topics like salary, marital status, age, religion, and education shortly after meeting.

While East Asian cultures shy away from physical contact, it is normal to ask new acquaintances questions that Westerners may consider to be prying. It's not unusual upon meeting someone at a party or a bar to be asked about salary, job title, personal relationships, education, and marital status.

In Korea, at least, such questions help Koreans determine a new acquaintance's social status. Social hierarchy is very important in East Asian cultures, particularly in business. The higher your status, the more respect you command and therefore the more likely it is that someone may help you out with a favor.

No matter how many times it happened, I found it initially jarring to be asked very personal questions (for an American) in the first few moments of meeting someone.

11. In many Asian cultures, it's considered extremely rude to place your chopsticks standing up in a bowl, as this is a symbol of death and funerals.

There's a reason every East Asian restaurant you visit has a rest block for your chopsticks: It is very bad etiquette to stick your chopsticks upright in a bowl. In multiple East Asian cultures, this has connotations of death and funerals.

At Japanese funerals, according to FluentU, a bowl of rice is left for the deceased with two chopsticks sticking upright. Meanwhile, in Chinese culture, the two chopsticks sticking up are said to resemble incense sticks burned at temples for dead ancestors.

While I knew better than to do this while visiting Asia, I watched other travelers and expats make the mistake in front of other East Asians. It was very uncomfortable.

12. It's considered rude to tip in Japan, Singapore, and some other Asian countries.

Tipping is ingrained in American culture — but that's not the case everywhere around the world.

For many in Asia, tipping is seen as rude because workers should do a stellar job as a point of pride, not because you've offered them extra cash. This is true in Japan and Singapore, though it is changing in some Asian countries as foreign tourism becomes a more important pillar of the economy.

When I visited Tokyo in 2017, I tried to give my taxi driver from the airport a tip. At first he kept handing the money back, thinking I had miscalculated the fare or misread the bills. When I tried to hand the money back to him, he realized that I was trying to tip him and he, rather curtly, shooed me out of the car. I only learned later that, by trying to hand him extra money, I was insulting his work ethic.

13. For people working in the tech industry in China, it's typical to work from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week.

Before arriving in China last April, I had heard rumors of the so-called "996" culture, which means that tech workers — and increasingly, young people in other industries, too — work 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. six days a week. One way of looking at it is that "996" is China's version of Silicon Valley's hustle culture, put on overdrive.

As I was visiting China to report on the tech industry, I found myself sucked into this lifestyle very quickly. Interview subjects were often looking to meet at their offices well into the evenings or on Saturdays. If I wanted to get the stories I was after, I had to adjust to their schedule.

By the time I left China after six weeks, I was exhausted from the work schedule. I can't imagine doing it for years. Some tech workers in China are starting to push back ,with mixed results.

14. It's common for Chinese workers to take a two-hour lunch break starting at noon that includes a nap in the office.

A few times early on during my visit to China, I tried scheduling interviews in the middle of the day. It was a bad idea and I didn't get any takers.

Lunch breaks in China for office workers start at 12 p.m. sharp and typically go until 2 p.m. That's not to say people are eating that entire time. Rather, most office workers will take a 30-minute nap in the office to recharge before the rest of the day.

It's a strange thing to see in action. When I visited the Alibaba headquarters in Hangzhou around midday, I found all the lights off in the office and nearly every person with either an eye mask and a blanket or a special pillow for sleeping on their desk. Some employees even roll out camp beds and sleep under their desks.

15. When sharing a meal in East Asian countries, the proper move is to fill everyone else's glass at the table before filling your own.

While the specific customs can differ dramatically by country — and you should research those specifics before you visit a place — in general, it is considered proper to pour drinks or tea for each person in your party before yourself.

In some places, like Korea, it is considered improper to ever fill your own glass. You fill others' glasses and wait for someone to fill yours.

While I quickly learned about the custom, I admit that I forgot about it from time to time, particularly when I was out drinking with a table of new friends. I have found that Asians tend to give foreigners some leeway for mucking up customs, but better to not mess it up at all.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement