Srinivasan’s advice bode well for the youngsters and made them very rich indeed but the operative word was “patient”. Despite zero signs of profitability in the ecommerce eddies, Srinivasan remains positive. After all, more than 20% of the GDP of the world comes from emerging markets with barely 3% of capital investment therein. In other words, there are not many tradable liquid securities out here, he reasons, adding that companies like Flipkart, Snapdeal and

“The rising tide will raise all the boats first and every company will get irrational valuations but those who focus on customer experience in the long term, will stay there and go higher, and those who don’t, will fall off,” says Srinivasan. As a precursor, he points to the dotcom boom in the US in 1999-2000. “Trillions of dollars went into valuations there but the customer experience only got better…so the irrationality of valuations is relative,” he points out, observing the Indian ecommerce market potential to be in the $100-200 range and with only $6 billion active market, excluding train and flight tickets, Flipkart’s valuation of $5 billion makes perfect sense.

“The rising tide will raise all the boats first and every company will get irrational valuations but those who focus on customer experience in the long term, will stay there and go higher, and those who don’t, will fall off,” says Srinivasan. As a precursor, he points to the dotcom boom in the US in 1999-2000. “Trillions of dollars went into valuations there but the customer experience only got better…so the irrationality of valuations is relative,” he points out, observing the Indian ecommerce market potential to be in the $100-200 range and with only $6 billion active market, excluding train and flight tickets, Flipkart’s valuation of $5 billion makes perfect sense.Today, the 44-year-old Kalyanaraman Srinivasan is Chief Operating Officer,

Education is salvation

Born and raised in Mannarkoil in Tamil Nadu’s Tirunelveli district, down south of Chennai, Raman’s father, a tehsildar, passed away when he was all of 15. The family of four siblings struggled through the odds on his mother’s monthly pension of Rs 420. She was, however, uncompromising on her children’s education. That explains how liberally Raman uses this phrase—“Education is salvation.”

After high school, Raman got through both medical and engineering college. While the medical college stood in his district, he opted for engineering in Chennai where he knew nobody. “I wanted to see how far I can fly,” he reminisces. Till today, Raman has a knack of making the tougher choice. It’s as if he’s conditioned that way. “The longer it takes to get something, the longer it stays with you….most of the things that look easy, are not good in the long term,” he says.

Raman’s first job was in Mumbai with Tata Consulting Engineers, where he landed up in slippers on his first day at work, sending his boss into a fit of rage. Upon hearing his story, he was not only given money to buy shoes but also fixed up at his friend’s Mumbai residence. Within a month, his boss sent him to Bangalore where he computerized the entire office administration. Thus started Raman’s steady rise in the world of information technology, and he did a lot of learning on his own, including ‘C’ programming. Just as he was about to get confirmed, he gave in his resignation since he signed up with TCS at Chennai. As a code jock, he ended up in Edinburgh servicing the Scottish Equitable Insurance Company and that’s where the first signs of friction with his boss became evident.

As Raman deep-dove into the world of insurance, he figured the mathematical model of the company was completely flawed—if the company had more than 15% reimbursement, the resultant number would be a big negative, while the marketing documents of the company said that people would get 23% redemption. He tried explaining it to his boss but got cold shouldered.

Raman would come in late and work well into the night. Being the last to leave, he was noticed by someone by the name Chris, who asked him why he stayed up so late despite being a programmer from an outsourced company. Upon being told of a questionable business model, Chris got curious and stayed up with Raman till 2 am one morning. A few days later, as Raman came in to work, his boss was pacing up and

down the room and glanced at him menacingly. He said that the European general manager of TCS had been called by the company and they were all going to see the management and that it concerned him. “If I were you, I would have packed my bags for India,” the boss said. Eventually, the trio entered a room with suits and at the head of the table, Chris sat in bespoke CEO attire. Before a word was uttered, Raman’s boss started making excuses and virtually disowned him, labeling him as a rotten apple in the TCS pantheon of “good and loyal workers”. That’s when Chris got up and silenced him, explaining why TCS needed to hire more people like Raman. “What my CPO and CIO couldn’t solve, a 22-yearold has done, and I thought it to be pertinent to acknowledge it in front of his bosses,” he said.

down the room and glanced at him menacingly. He said that the European general manager of TCS had been called by the company and they were all going to see the management and that it concerned him. “If I were you, I would have packed my bags for India,” the boss said. Eventually, the trio entered a room with suits and at the head of the table, Chris sat in bespoke CEO attire. Before a word was uttered, Raman’s boss started making excuses and virtually disowned him, labeling him as a rotten apple in the TCS pantheon of “good and loyal workers”. That’s when Chris got up and silenced him, explaining why TCS needed to hire more people like Raman. “What my CPO and CIO couldn’t solve, a 22-yearold has done, and I thought it to be pertinent to acknowledge it in front of his bosses,” he said.The American Dream

For Raman, there was no looking back. With the help of Chris, he applied to companies in the US and got through

Galvanizing Groupon

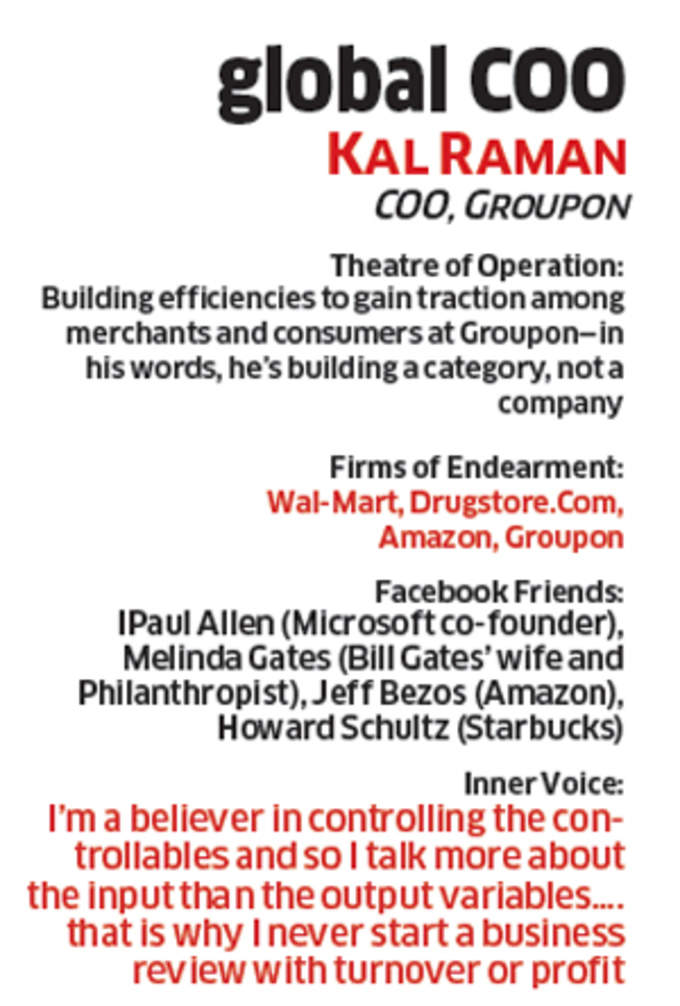

In 2012, Groupon’s international business was crumbling and it was left to Raman to steady the ship. Today, along with the domestic US business, the international division is in the black. “We are building a category, we are not building a company…. what Groupon is now, Amazon was in 2001,” he says.

As he pumps in adrenaline to the business, Raman has a roadmap. He’s applying all that he learnt at Wal-Mart, keeping the merchant community engaged and customers happy by offering the lowest prices and an efficient delivery mechanism. Will he be able to pull it off? “We’re more worried about the long term and so we’re trying to get more efficient by passing off the savings to our merchants and customers so that they become more loyal to Groupon and check our website first before they go for any other transactions….we have about 1,600 people in technology to do that out of 12,000 worldwide,” he says. At $2.5 billion revenue and with zero debt, Raman’s optimism is well-founded. And while valuations like $8 billion scorch the terrace, he maintains a straight face and waits for the tide to raise the boats. What then, after he steers Groupon to the safe shores of supra-growth and profitability? “I’ll do something very big in education in India, with or without Groupon,” he says.