- Home

- international

- news

- The 3,000-year history of tunnel warfare shows how hard it's going to be for Israel to root out Hamas

The 3,000-year history of tunnel warfare shows how hard it's going to be for Israel to root out Hamas

Elias Chavez

- Tunnel warfare has been used since the 9th century BC.

- Tunnels provide advantages in warfare by providing cover and secrecy.

Tunnels have been used in warfare for centuries. The first known use of the tactic dates back to the Ancient Romans and Persians, who would tunnel under barricades and walls to enter city walls and fortresses.

World War I saw the use of tunnels loaded with so many explosives that they changed the landscape of Germany. North Korea and Vietnam used increasingly extensive and complex tunnel systems during times of war to evade and outsmart their enemies.

More recently, Hamas militants have built a series of underground tunnels known as the "metro." The tunnels are reinforced with concrete and iron bars, and some are big enough to fit a truck through.

"Having tunnels as part of a landscape of warfare makes it very, very difficult for an invading army to be successful," Howard Stoffer, a professor of national security at the University of New Haven, told Insider. "Because they provide tremendous advantages to the defense, and I think they're [Hamas] using them very effectively."

Tunnel warfare provides safety from air attacks and wards off detection. With an expansive and reinforced tunnel system, Israel faces a major challenge in rooting out Hamas.

Tunnel warfare has been used since the 9th century BC.

Originally called "mines" instead of tunnels, ancient Assyrians in the 9th century BC would get as close to a city wall as possible and try to undermine its foundations.

Because digging took so long and exposed them to fire from above, ancient civilizations realized that the safest approach was to start a tunnel further away and dig toward city walls.

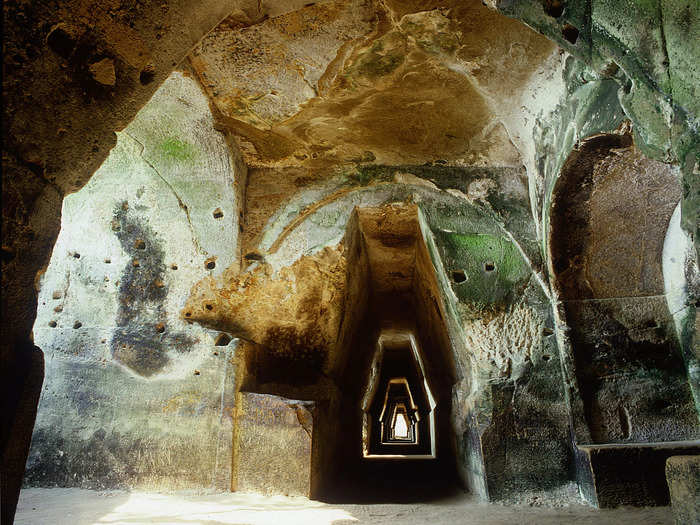

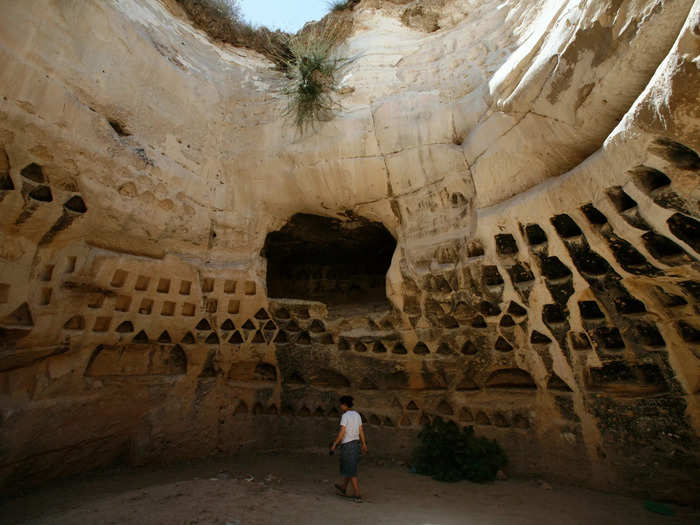

Israelites built a vast network of 450 tunnels — some of which were used against the Roman Empire.

The tunnels in Israel date back to the first century BC and were used for myriad purposes.

Jewish rebels used tunnels to revolt against and hide from the Roman Empire. The network of tunnels is expansive, with some tunnels leading to trap doors in villages or large columbariums.

The tunnels provided escape routes and shelter from the Roman Empire during the Bar Kokhba revolt.

However, the Roman Empire overwhelmed the Jewish rebels and won the war, eventually tearing up the streets, finding the tunnels, and taking their village.

The tunnels are full of relics from the past, from ancient weapons and oil lamps to olive presses and cooking pots.

Ancient Persians and Greeks also employed early chemical warfare tactics in tandem with the tunnels.

In addition to destroying the foundations of defensive walls, ancient Greeks and Romans utilized early chemical warfare in tandem with tunnel warfare to infiltrate cities. During a battle in 189 BC, ancient Greeks burned chicken feathers to smoke out Roman invaders.

The advent of tunneling brought on the use of countermines, defensive tunnels built inside a city wall constructed to locate or trap tunneling from the outside.

When Persians dug tunnels underneath the walls of Dura-Europos, a Roman-held Syrian city, the Romans began digging counter tunnels to stop the invasion. But the Persians were aware of their enemy's strategy.

As the Romans began to emerge from the tunnels, the Persians blew poisonous smoke made from burning sulfur and bitumen at them, which turned into sulfuric acid in their lungs.

"It would have almost been literally the fumes of hell coming out of the Roman tunnel," Simon James, an archaeologist and historian from the University of Leicester, told LiveScience.

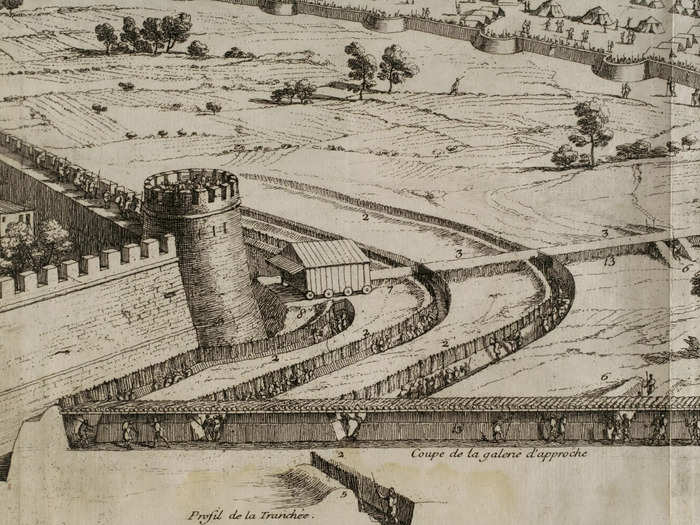

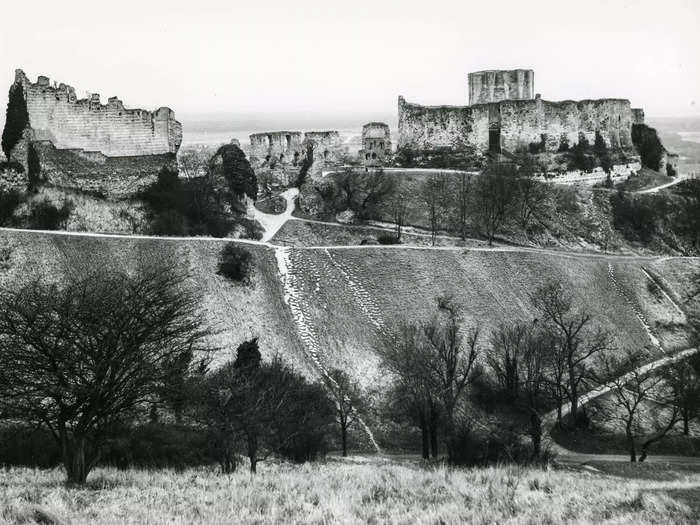

Tunneling continued into the Middle Ages as fortress warfare was still dominant.

Tunneling always poses high risks. If done incorrectly, a tunnel may collapse, and if a counter tunnel is successful, there is very little room to escape.

At the siege of Château Gaillard, a castle built by Richard the Lion-Hearted, in 1203, French soldiers overcame castle walls by digging tunnels underneath them.

In such cases, tunnels come with high rewards. The French tunnels brought them to an unguarded toilet chute that allowed entrance into the château, thus turning the tide of the siege.

Not every tunnel attempt was successful.

During the Civil War, Union forces used the miners in their ranks to build a 510-foot tunnel beneath the Confederates, fill it with four tons of gunpowder, detonate it, and bring a swift end to the war.

After weeks of preparation, the Union set off their explosion and rushed into the resulting crater.

Though the attack did lead to hundreds of enemy casualties, the subsequent assault by Union soldiers was disorganized and poorly executed. Instead, they found themselves in the bottom of a crater surrounded by Confederate soldiers who made quick work of their mistake.

The attack resulted in 4,000 Union casualties and only 1,800 Confederate casualties. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside was relieved of his unit for his role in the devastating defeat.

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant called the Battle of the Crater "the saddest affair I have witnessed in this war."

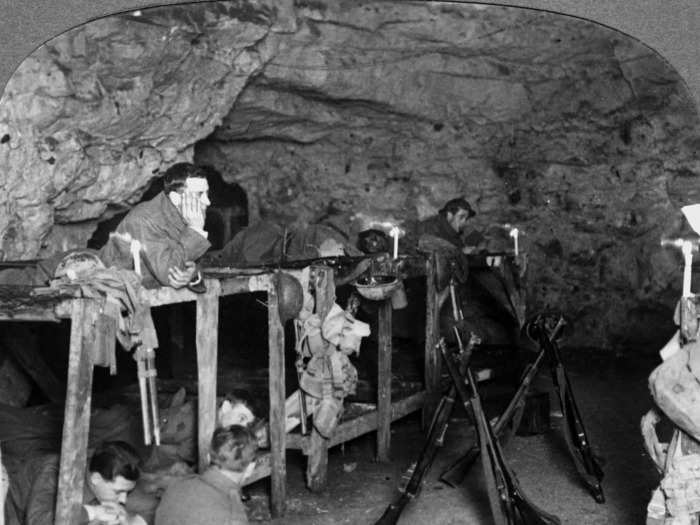

Trenches and tunnels played a key role in World War I.

World War I is widely known for the heavy use of trench warfare. Though not a new practice, trenches provided protection from an array of new military technology, like machine guns, aircraft and tanks.

Trenches were not the only thing being dug into the ground. Allies and Central Powers both used tunnels and explosives to gain the upper hand.

At the Battle of the Somme in 1916, French sappers built 22 tunnels in 18 months underneath German trenches.

The tunnels were then stuffed with 450 tons of TNT, equating to nearly 1 million pounds of explosives. The result was the largest explosion before the nuclear era.

Shortly before the detonation, British Maj. Gen. Charles Harington told his army, "Gentlemen, we may not make history tomorrow, but we shall certainly change the geography."

The large blast off of the Messines-Wytschaete ridge killed as many as 10,000 German soldiers.

The French spent $9 billion on a 280-mile series of tunnels connected by diesel railway for World War II.

The tunnels connected various fortresses, infirmaries, bunkers, and artillery depots. The tunnels were reinforced with concrete and steel and designed to withstand whatever the German army could throw at them.

Despite the tunnel's technical ingenuity, the French had spent their time preparing for the methods of wars past. Advances in military tactics and machinery ultimately left the tunnels useless against German air raids.

The Viet Cong used tunnels to great effect.

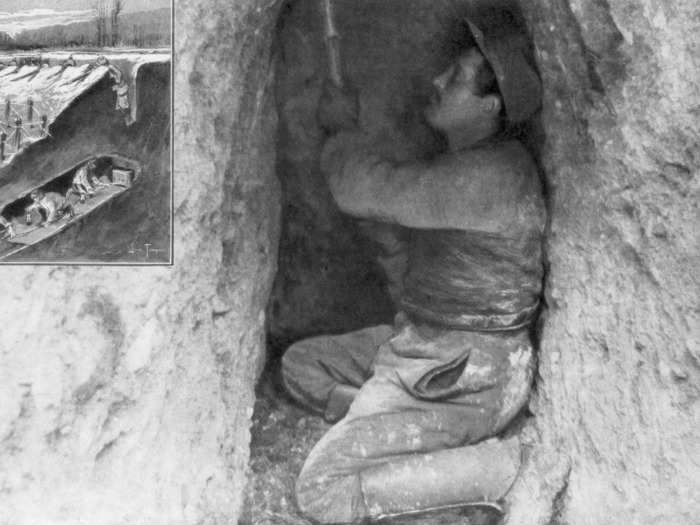

During the Vietnam War, the Viet Cong's guerilla warfare tactics baffled and infuriated enemies. Among these tactics was the vast network of small and advanced tunnels they utilized dispersed across Vietnam.

The tunnels used by the Viet Cong were filled with traps, infirmaries, kitchens, and even movie theaters.

The Viet Cong built tunnels with blind alleys and trap doors and even filled some passageways with water.

The tunnels proved difficult for the US Army to thwart. Bombs were ineffective in collapsing tunnels, dogs succumbed to traps, and gas didn't work in the large tunnel networks.

A group of small and brave soldiers, known as "Tunnel Rats," were responsible for clearing the Viet Cong from the tunnels.

Capt. Herbert Thornton, known as the father of the Tunnel Rats, said they "had to have an inquisitive mind, a lot of guts, and a lot of real moxie in knowing what to touch and what not to touch to stay alive—because you could blow yourself out of there in a heartbeat."

One of the most advantageous aspects of the Viet Cong's tunnels was their size and secrecy.

It took time for American soldiers to learn about the Viet Cong's tunnel system.

In one instance, The United States Army set up Camp Cu Chi directly above a series of the Viet Cong's tunnels.

While the soldiers were sleeping, the Viet Cong would exit their tunnels and wreak havoc on the camps. Despite the US Army bombing the area, the Viet Cong remained safe in their tunnels.

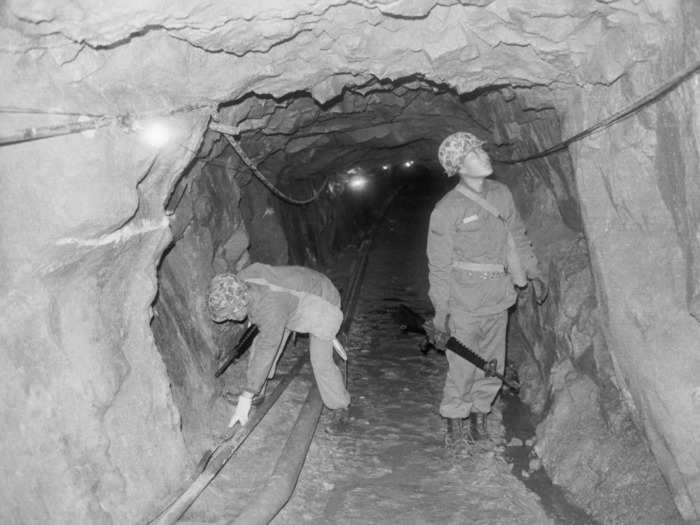

North Korea dug tunnels through the DMZ into South Korea.

In 1974, North Korean defectors informed South Korean officials that North Korean leader Kim Il-sung had ordered army units to dig tunnels beneath the demilitarized zone.

Between 1974 and 1990, the South Korean government found four tunnels. One tunnel, around 30 miles south of Seoul, could accommodate the passing of 30,000 troops an hour.

Some estimate there are still more tunnels underneath the DMZ leading into South Korea, but none have been found in the decades since the last discovery.

ISIS was also well known for using tunnels to their advantage.

ISIS had a network of tunnels that cross underneath various cities and villages. The tunnels allowed them to move fast, avoid detection, and strike targets quickly.

"There's the war on the streets and there is a whole city underground where they are hiding," Col. Falah al-Obaidi, part of the Iraqi counterterror forces, told The Washington Post. "Now it's hard to consider an area liberated, because though we control the surface, ISIS will appear from under the ground, like rats."

The tunnel system was vast and extensive. Some have even been found with dorms, wallpaper, and kitchens.

To avoid detection by satellites and drones, the Islamic State hid dirt from their digs in nearby houses.

The expansive tunnel systems helped ISIS avoid detection by drones and provided safety from bombs.

Hamas militants are currently using a network of tunnels in their conflict with Israel.

The Hamas tunnel system is known as "the metro" and has been described as an underground "spiders-web" by an 85-year-old hostage whom Hamas recently released.

"They run for miles. They are made of concrete and very well made," a Western security source told Reuters. "Think of the Viet Cong times 10. They have had years and lots of money with which to work."

The tunnels are believed to extend 300 miles. Access points into these tunnels are found in hospitals, schools, and other civilian buildings.

Hamas' network of tunnels presents additional problems for Israel.

Despite the heavy bombing of Gaza, dropping over 6,000 bombs in the first six days of the war with Hamas, the Hamas' "metro" is reinforced and harder to hit.

Even if Israel can collapse some of the tunnels, it remains difficult to know how many more there are. Hamas fighters can use the tunnels as a refuge, command centers and arms caches, and to launch surprise attacks on Israel's troops within the cluttered urban space and dart back in before Israel can respond.

"There are troops in the Israeli army and we've sent over [US Army] experts to work with them in figuring out how to go into the tunnels and be able to confront Hamas," Stoffer said. "And that is extraordinarily dangerous work. It's complex. And that might be the only way if you're not going to bomb from above."

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement