The Avro Canada VZ-9AV Avrocar on display in the R&D Gallery at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.U.S. Air Force photo by Ty Greenlees

- The VZ-9AV Avrocar was an attempt to build a stealthy aircraft that could fly at high speeds.

- The project was projected to cost $3.16 million in the 1950s, approximately $26 million today.

It's not from outer space, but it sure does look like it.

In the 1950s, the Canadian Air Force wanted to create a vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) vehicle that could hover below radars, intercept enemy planes, and take off at high speeds. The VZ-9AV, with its unique saucer shape, was the proposed solution.

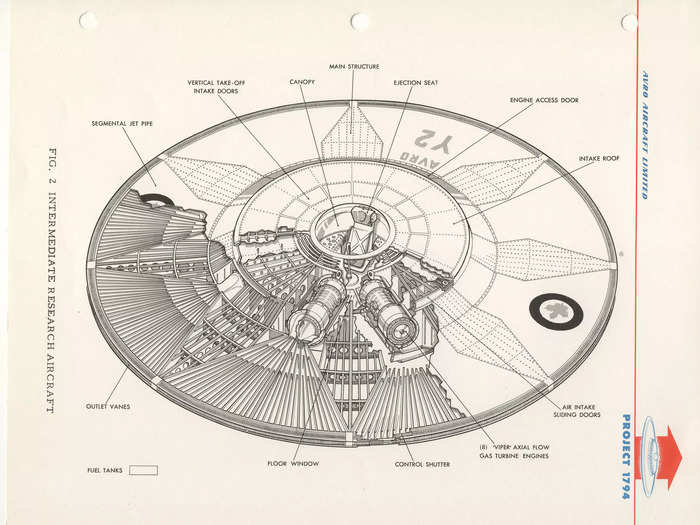

The designer, John Carver "Jack" Frost, designed the Avrocar to take advantage of the Coanda effect, a principle that dictates fluid follows a curve, to provide lift and thrust from one engine by blowing exhaust out of the rim of a circular aircraft.

Original designs and tests for the Avrocar suggested it would be able to fly at three times the speed of sound. As the building continued, the project became too expensive, and in 1958, the US government took over the remainder of the project's funding.

However, after months of research and design, the prototype was not even able to make a full ascension into the sky and only ever achieved a sustained hover three feet above the ground.

The design was eventually scrapped, and the aircraft was never revisited. In 2007, the aircraft was acquired by the National Museum of the United States Air Force and has since been restored.

The Avrocar may look like a flying saucer from a sci-fi movie, but it was intended for practical purposes.

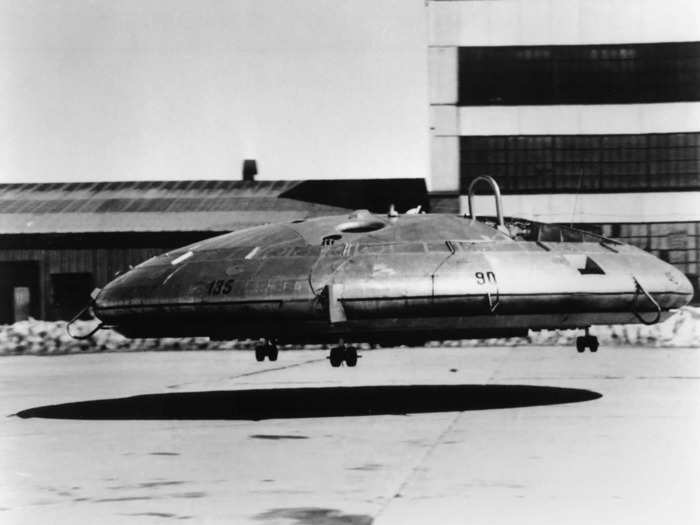

The Avrocar is being rolled out for one of its initial test flights. US National Archives

The Canadian Air Force wanted an aircraft that could take off vertically, fly under radar scans, and intercept enemy ships.

Initial designs for the plane promised that it would be able to achieve speeds three times the speed of sound, thus creating the supersonic fighter bomber the Canadians wanted.

The circular design of the ship was more than an aesthetic choice.

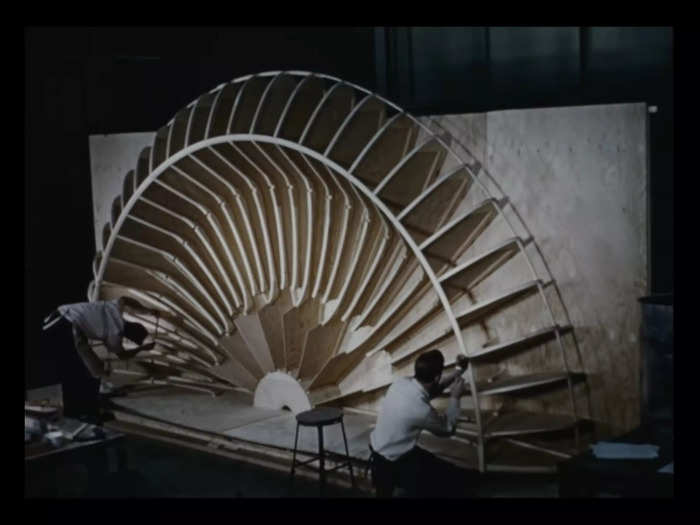

Two engineers work on a wooden skeleton for a to-scale model of the Avrocar. United States National Archives

John Carver "Jack" Frost was a respected aircraft designer who aimed to leverage the Coanda effect to benefit a circular aircraft.

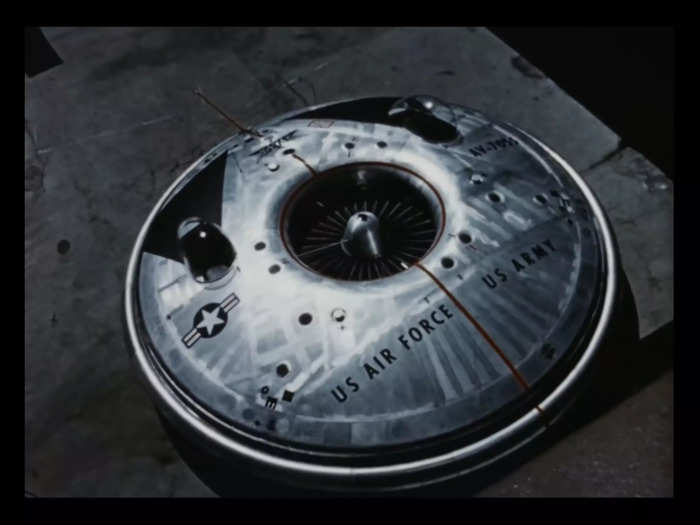

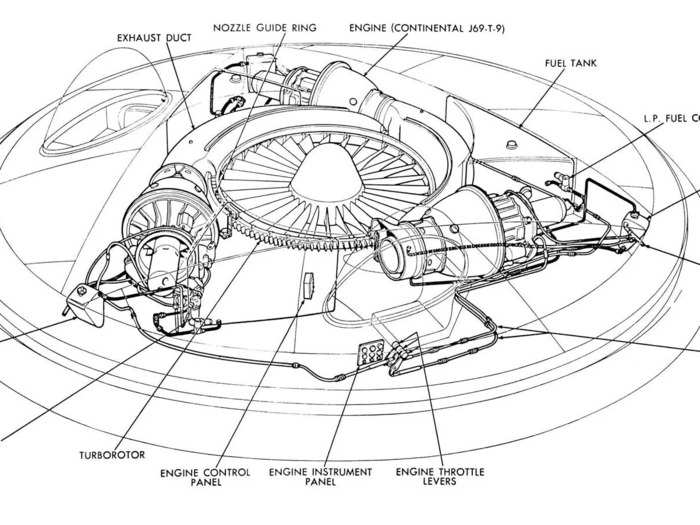

The circular design of the ship would utilize turbojet engines to drive a "turbo rotor" and produce thrust.

The blueprints for the Avrocar display the engine layout for the aircraft. U.S. Air Force

The vents and fans in the Avrocar would direct the thrust downward and create a cushion of air that would allow the Avrocar to float at low altitudes.

If the thrust were directed to the rear of the aircraft, it would be able to accelerate and gain altitude.

Initial designs for the Avrocar utilized several turbojet engines surrounding the ship's center.

A diagram of the early designs for the Avrocar displaying a center seat surrounded by turbine engines. US National Archives

Initially, the Canadian government provided funding. However, as the building continued, it proved to be too expensive. The initial estimate for completing the project was $3.16 million, or $26 million today.

In 1958, the US government took over the remainder of the project's funding, and things became complicated. The Army and the Air Force were interested in the Avrocar for different reasons.

The A.V. Roe team built two models to satisfy the US Army and the Air Force.

The pilot of the Avrocar stands up in the vehicle after a test flight. US National Archives

The Army wanted a "durable and adaptable, all-terrain transport and reconnaissance aircraft" to replace the current light observation craft as well as helicopters.

The Air Force was more intrigued by the Avrocar's vertical take-off and landing capabilities. If everything went to plan, the aircraft could potentially hover below enemy radar and accelerate to supersonic speed.

The final Avrocar was 26 feet in diameter, five and a half feet tall, and weighed more than 5,000 pounds.

The Avrocar during an initial test flight with a pilot in one of the two seats. US Air Force

Engineers predicted that the Avrocar would reach heights of nearly 10,000 feet.

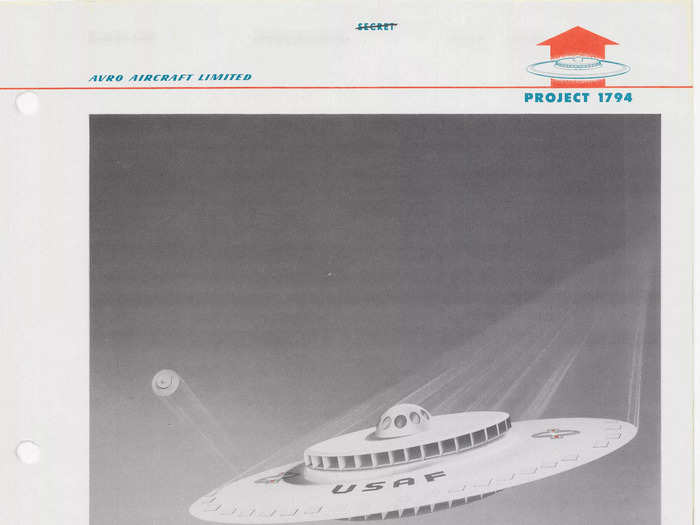

An illustration included in the program planning report. US National Archives

However, testing soon showed that the Avrocar wouldn't grace the skies anytime soon.

The Avrocar hovers just three feet above the ground during testing. US Airforce

The Avrocar would become unstable when lifting more than three feet above the ground.

The lack of computer technology available at the time and the design flaws of the craft required pilots to control each engine separately, which proved incredibly difficult.

By December 1961, the project was scrapped, and the Avrocar was put away for good.

Museum attendees point at and observe the Avrocar. US Air Force/Ty Greenlees

The team of engineers working on the project discovered that the circular design of the craft was not very aerodynamic, nor did it lend itself to stealth.

Additionally, the A.V. Roe team discovered the craft couldn't exceed 35 miles per hour.

But the endeavor wasn't a complete failure.

An F-35B prepares to land on the flight deck of UK Carrier Strike Group HMS Queen Elizabeth. PUNIT PARANJPE/Getty Images

Aircraft like the AV-8B Harrier II, V-22 Osprey, and the F-22 Raptor use technology discovered during the Avrocar process.

Planes like the F-35B can perform short take-off maneuvers. The lifting fan necessary to perform such maneuvers was developed while working on the Avrocar.

In 2007, the National Museum of the US Air Force acquired and restored one of the test models.

Volunteers Ed Keinle and Lou Thole remove rivets from the Avrocar in the restoration hangar at the National Museum of the United States Air Force. US Air Force

The other prototype was acquired by the US Army Transportation Museum in 2019.

The Avrocar in the restoration hangar. US Air Force